Salvete, readers and history-lovers!

Welcome to The World of The Stolen Throne!

In this five-part blog series, we’re going to be taking a look at the research that went into the latest Eagles and Dragons novel, The Stolen Throne.

Over the next few weeks, I’ll take you on a journey from the world of early third-century Roman Britain to the lands of Dumnonia. As The Stolen Throne is a more mysterious episode in the Eagles and Dragons series, we will also be looking at relevant parts of Celtic mythology, in addition to some history and archaeology related to the story and setting of this book.

In this first post, we’re going to be taking a brief look at one of the settings in The Stolen Throne. The Roman town of Isca Dumnoniorum serves as a sort of gateway to the unknown in the story, a final vestige of the Roman world before the characters continue on their journey.

Many towns in Roman Britain tend to eclipse Isca Dumnoniorum, but this settlement played an important role in the early stages of Romanization of the island. How was it established and what purpose did it serve?

Let’s find out.

In 55 and 54 B.C. the forces of Julius Caesar attempted to reconnoitre and invade the mysterious and unknown, until then, land of Britain. The second campaign experienced some success, but the full-scale invasion of Britannia did not occur until nearly a hundred years later with the Claudian invasion of the island.

In A.D. 43, Emperor Claudius’ forces landed on the shores of the island, changing the course of history for good this time. Four Roman legions and auxiliaries landed in what is now Kent. The force is said to have consisted of over 45,000 men.

Many battles were fought, and peace treaties were signed with the tribes southern Britain. It was during this time that the future emperor, Vespasian, stormed the southern hill forts of Britain, particularly in the lands of the Durotriges and Dumnonii. The great hillforts of South Cadbury Castle and Maiden Castle were a part of this offensive campaign.

This invasion was just the beginning of what was to be a forty-year campaign to subdue the Britons and bring the island into Rome’s Empire.

One of the legions commanded by Vespasian in his southern sweep was the famous II Augustan legion.

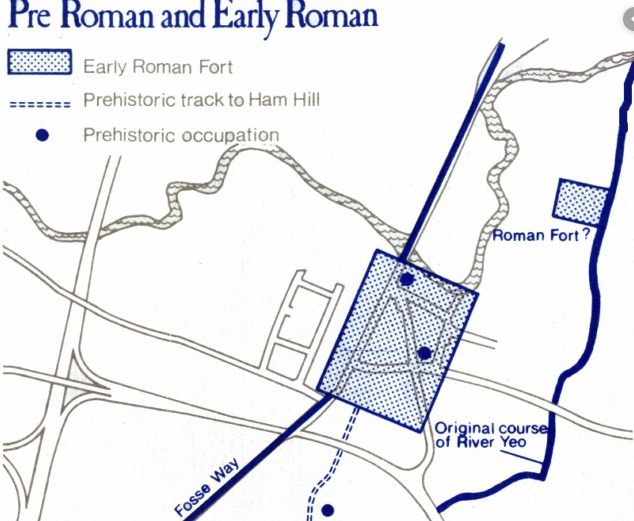

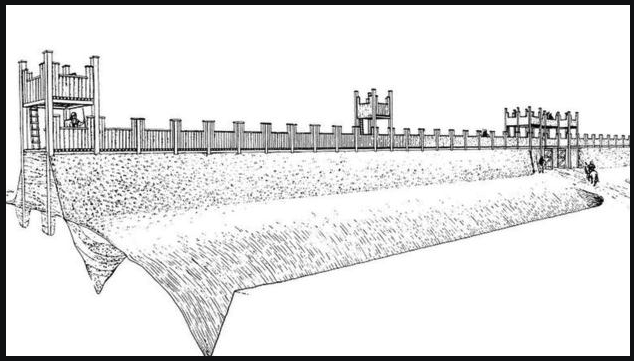

The legion’s first, permanent base, a forty-two acre castrum, was established at Isca Dumnoniorum, or modern Exeter, in around A.D. 55, with smaller forts being established in the surrounding region in the Quantock and Brendon Hills, and the Vale of Taunton Deane.

Isca Dumnoniorum was the largest base in the southwest. It had everything one would expect from a large, legionary base, including barracks, granaries, and workshops, which were made of timber. There was a stone, military bathhouse which was fed by an aqueduct leading from a nearby natural spring. Archaeologists have also discovered a cockfighting pit in the remains of the palaestra (outdoor exercise yard) which was attached to the bathhouse. Seems like the men of the legions enjoyed a bit of sport when off duty!

Like other Roman settlements in Britain, Isca’s beginnings were martial, and not long after it was established, one of the most violent episodes of this period occurred.

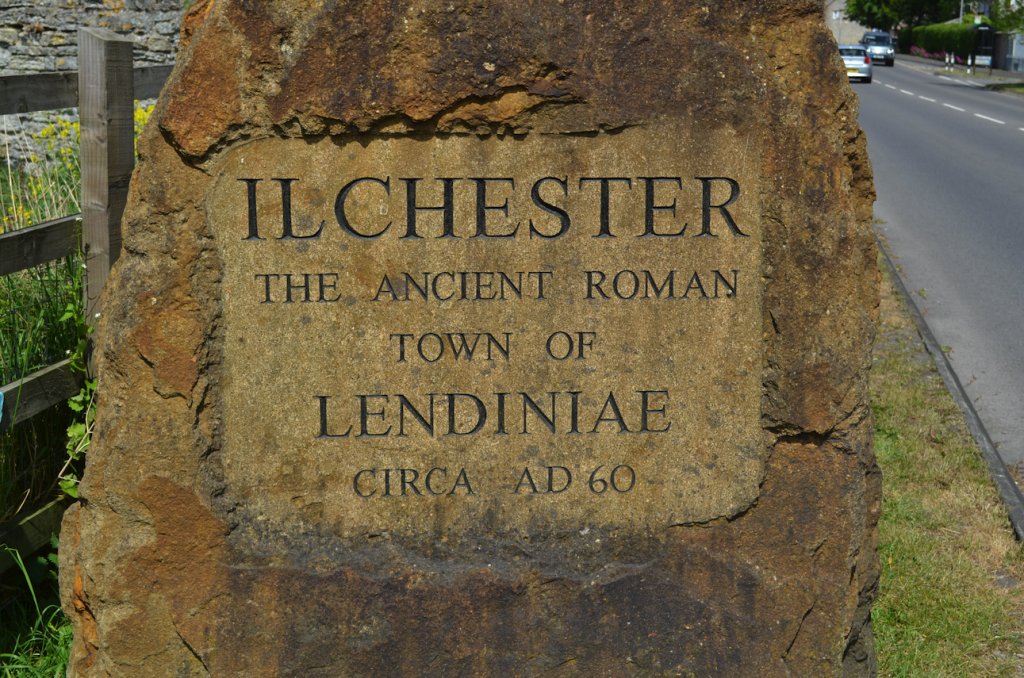

In A.D. 60, Queen Boudicca of the Iceni led her revolt against Rome and during that time, settlements across the land such as nearby Lindinis shored up their defences.

According the Tacitus, Poenius Posthumus, camp prefect of the II Augustan, based as Isca during the Boudiccan revolt, refused to support Governor Suetonius Paulinus against the rebels because of a personal argument, or because he did not want to threaten the tenuous peace he held over the Durotriges of Somerset.

Poenius Postumus, camp-prefect of the second legion, informed of the exploits of the men of the fourteenth and twentieth, and conscious that he had cheated his own corps of a share in the honours and had violated the rules of the service by ignoring the orders of his commander, ran his sword through his body. (Tacitus, Annals, XIV, 37)

It was not a proud moment for the II Augustan, after their strong showing in the initial invasion. Nevertheless, the legion based at Isca would go on to form part of the military backbone of Roman Britain for a long time afterward.

Artist impression of the early fortress defences of Isca Dumnoniorum (Exeter City Council Archaeological Field Unit)

When the smoke of the Boudiccan revolt eventually cleared, the Roman peace in southern Britannia could begin to take hold.

One of the ways in which Rome brought their newly-conquered subjects into the fold was through the establishment of civitates, administrative centres based on old tribal regions.

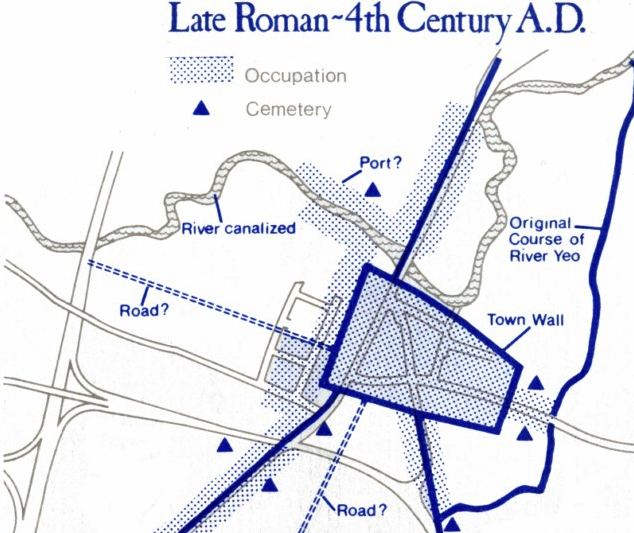

The three civitates of the southwest were Corinium Dobunnorum (capital the Dobunni at Cirencester), Durnovaria (capital of the Durotriges at Dorchester), and Isca Dumnoniorum (capital of the Dumnonii at Exeter). These civitates, and others like them across the land, were an important part of the process of Romanization, as well as citizenship, and the spread of Roman ideals.

As part of the process, a vicus (civilian settlement) began to form outside of the fortress’ walls where tradesmen and families of the troops lived.

After twenty years based there, the men of the II Augustan legion moved to what would become their permanent base at Caerleon (Isca Silurum), in southern Wales. However, Isca Dumnoniorum remained as an important settlement and centre of administration and trade, especially when it was made an official civitas.

As a civitas, Isca was governed by a council known as an ordo, a sort of small senate. The members of the ordo, the decurions, were responsible for local justice, public shows, religious festivals, public works such as roads, water supply and building, taxation, and the census. Ordo members also represented Isca’s interests in the provincial capital of Londinium.

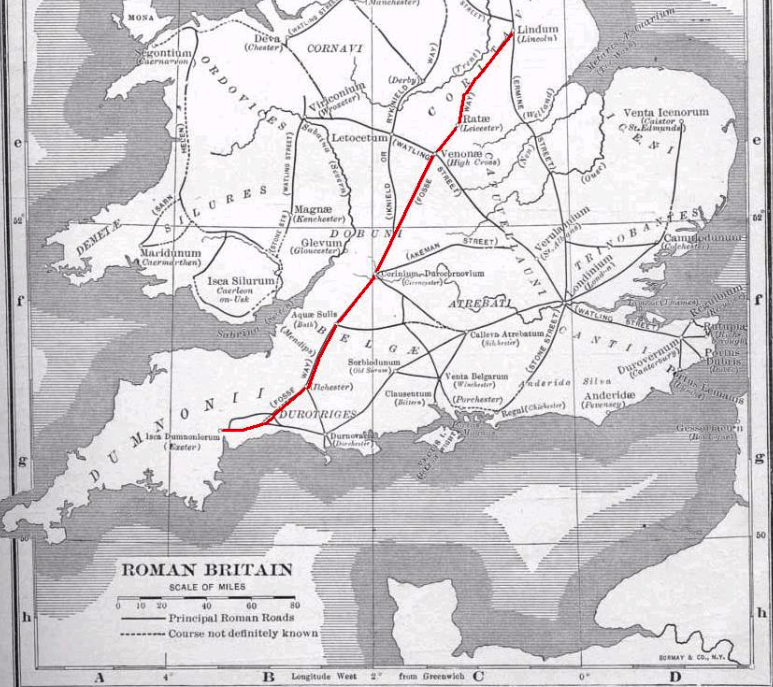

Roman Roads in Britain with the Fosse Way in Green, running from Isca Dumnoniorum to Lindum (Wikimedia Commons)