Welcome back to The World of The Stolen Throne.

In Part III, we looked the Arthurian sites on Bodmin Moor that inspired part of The Stolen Throne. If you missed it, you can read that HERE.

In Part IV, we’re going to be taking a brief look at one of the major settings in The Stolen Throne. It is a place that is firmly entrenched in Arthurian myth and legend, but also in the history of Dumnonia itself. Let us visit the dramatic site of Tintagel Castle.

Aerial view of Tintagel Castle (photo: English Heritage)

And as he [Gorlois, Duke of Cornwall] was under more concern for his wife than himself, he put her into the town of Tintagel, upon the sea-shore, which he looked upon as a place of great safety… The king [Uther Pendragon], informed of this, went to the town where Gorlois was, which he besieged, and shut up all the avenues to it. A whole week was now past, when, retaining in mind his love to Igerna, he said to one of his confidants, named Ulfin de Ricaradoch: “My passion for Igerna is such that I can neither have ease of mind, nor health of body, till I obtain her: and if you cannot assist me with your advice how to accomplish my desire, the inward torments I endure will kill me.”—”Who can advise you in this matter,” said Ulfin, “when no force will enable us to have access to her in the town of Tintagel? For it is situated upon the sea, and on every side surrounded by it; and there is but one entrance into it, and that through a straight rock, which three men shall be able to defend against the whole power of the kingdom. Notwithstanding, if the prophet Merlin would in earnest set about this attempt, I am of opinion, you might with his advice obtain your wishes.”

(Historia Regum Britanniae, Geoffrey of Monmouth, Book 8, 19)

The words above are what set Tintagel Castle firmly on the map of Arthurian myth and legend, associating it the birth of the figure we have come to know as King Arthur.

If you have read the stories, or seen movies such as Excalibur, you will be familiar with this setting.

But what exactly was Tintagel Castle?

In The Stolen Throne, the latest novel in the Eagles and Dragons series, which takes place during the third century A.D., it is the ancestral seat of one of the main characters, a prince of Dumnonia. But was it in use at this time? What is the evolution of this mysterious place?

In this post, we’re going to look at Tintagel Castle itself, some of the remains and finds, and how archaeology has brought to light new and exciting theories about this fascinating place of myth and legend.

Modern footbridge from mainland castle court to Tintagel Rock (photo: CNN)

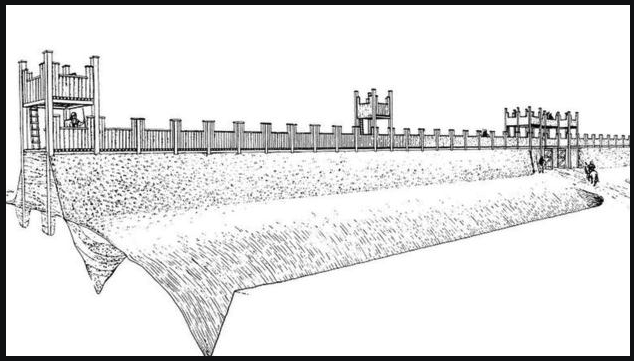

The name of Tintagel actually comes from the Celtic name ‘Din Tagell’, which means ‘Fortress of the Narrow Entrance’. Most believe that this refers to the mainland approach which was by way of a narrowed, defensible passage at first between embankments, and later through the medieval gatehouse.

Tintagel is located on the north coast of Cornwall in one of the most dramatic settings around. From the narrow part of the mainland that forms the approach, one had to cross a bridge high above a rocky chasm to reach the castle rock itself, which juts out into the sea. The castle sits 250 feet above the rough water.

This place was meant to be impenetrable, if not practical.

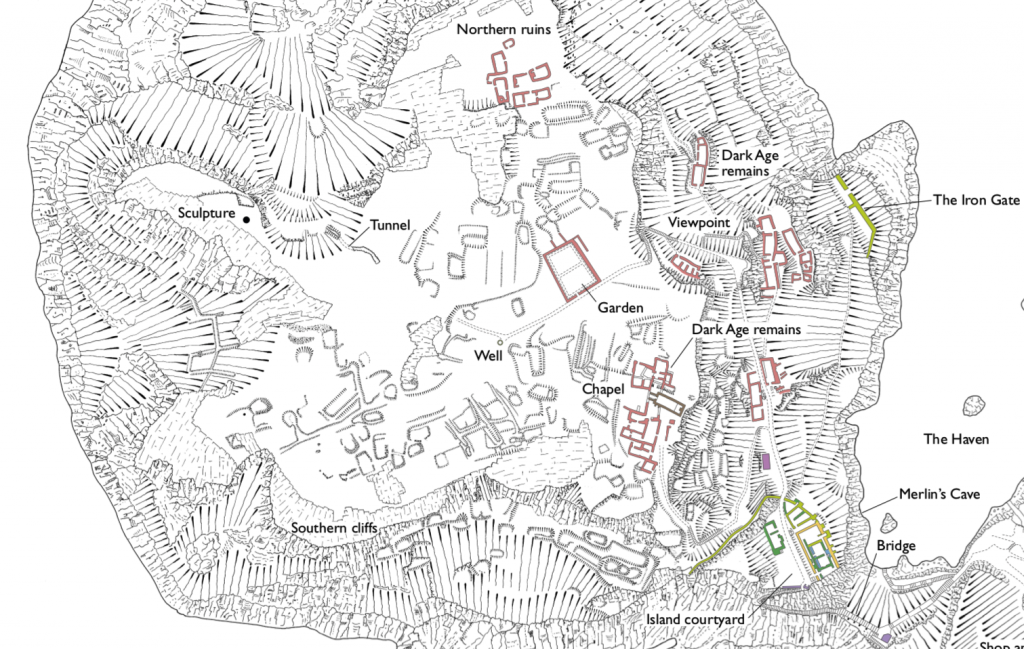

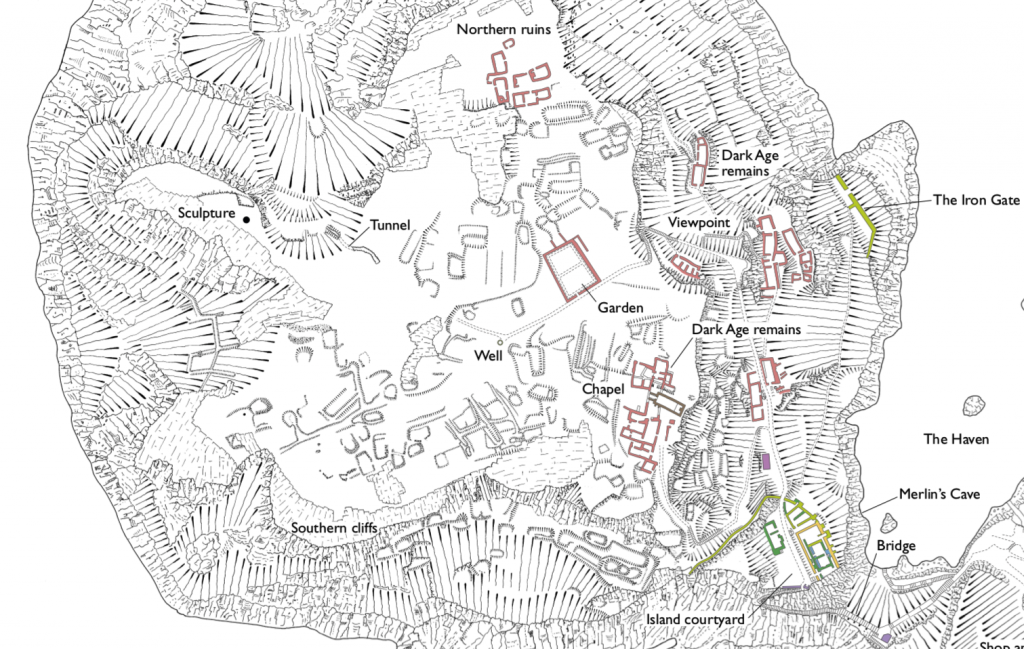

Site plan of Tintagel Castle (English Heritage)

Most of what is visible today, including the romantic ruins of the inner courtyard and great hall were built by Richard, Early of Cornwall after 1233. It has been suggested that as Tintagel was such a weatherbeaten and impractical place to build and live, Earl Richard may have done so only to maintain a connection with the prestige of its Arthurian past which was firmly believed at that time, a hundred years after Geoffrey of Monmouth’s medieval bestseller put Tintagel on the map.

The impressive medieval ruins include the mainland gatehouse and courtyard, the island courtyard and great hall, as well as a chapel, tunnel and walled garden on the summit of the plateau.

They are some of the most romantic ruins in Britain.

Romantic ruins of Tintagel’s Medieval castle

Despite the fact that Tintagel castle was a difficult place to build, with the slate foundations of the rock being constantly eroded by the lashing sea, it seems to have played an important part in Dumnonia’s history.

Before we get to the Arthurian connection, let’s discuss what might have been happening at Tintagel during the Roman period.

In The Stolen Throne, I had to take some poetic license when it came to the structures that were located on the castle rock. However, there was, it seems, activity at Tintagel during the Iron Age and years of the Roman occupation of Britain.

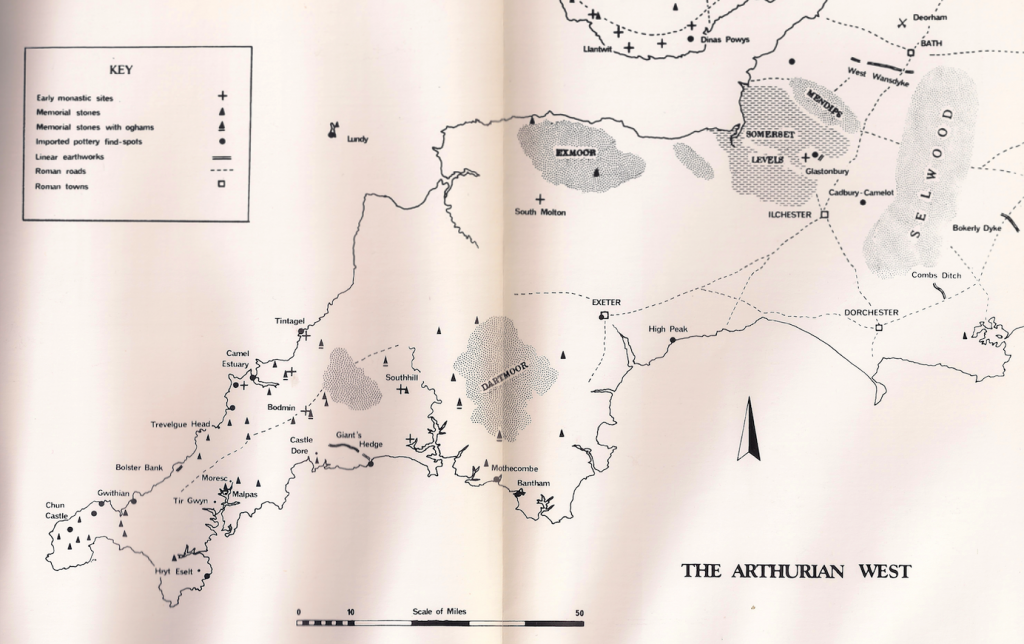

Tintagel, during the Roman period, was a small settlement on the very edge of the Roman Empire. It has been suggested that it may be the place known as ‘Durocornovium’, a place mentioned on a list of Roman roads (though a location near Swindon seems more likely).

Tintagel’s Castle rock visible from the opposite cliffs on landward side

Nevertheless, archaeologists believe that during the 3rd century A.D. a small village or settlement may have been established on the mainland facing the castle rock, around the area of the narrow approach to the island.

Tintagel was part of Dumnonia and seems to have received little attention from the Roman authorities based at Isca Dumnoniorum (modern Exeter). That is, until it was discovered that the land in Dumnonia was rich in tin, and mining operations began.

There was no Roman settlement at Tintagel, but a Roman road did pass nearby, presumably giving access to the mines and few forts located in that part of Britain. Further proof of the roads is available in the form of two Roman milestones to either side of Tintagel, on the mainland.

Roman stone in Tintagel’s Parish Church (Wikimedia Commons)

No Roman buildings have been found at Tintagel castle as yet, but it should be noted that only about 5% of the castle area has been excavated. Who knows what remains lie beneath the grass and soil of that windswept rock jutting out into the sea?

Despite the lack of buildings, some of the most exciting Roman finds to come out of the ground at Tintagel are a purse containing Roman coins and, more importantly, a huge quantity of Romano-British and Mediterranean pottery.

Stone disks used to seal amphorae, and ceramic sherds from Greek amphorae used for transporting wine and olive oil, found at Tintagel (photo from archaeology.org)

The amount of Mediterranean pottery discovered at Tintagel from the 3rd century to the Dark Ages is said to be a greater quantity than the total amount that has been discovered from all other Dark Age sites in Britain put together. It is believed that this points firmly to habitation at Tintagel castle in the third and fourth centuries A.D.

The presence of such prestige goods at Tintagel means not only that it was an important place for the rulers of Dumnonia, but also that it was an important place for trade on the sea routes from the continent to the western isles and northwest Britain.

View of Tintagel beach, the ‘Haven’, Merlin’s cave, the causeway and part of the castle

The sandy beach below Tintagel castle, known as ‘the Haven’, made it possible for ships to unload safely, but this was not the only place they could unload.

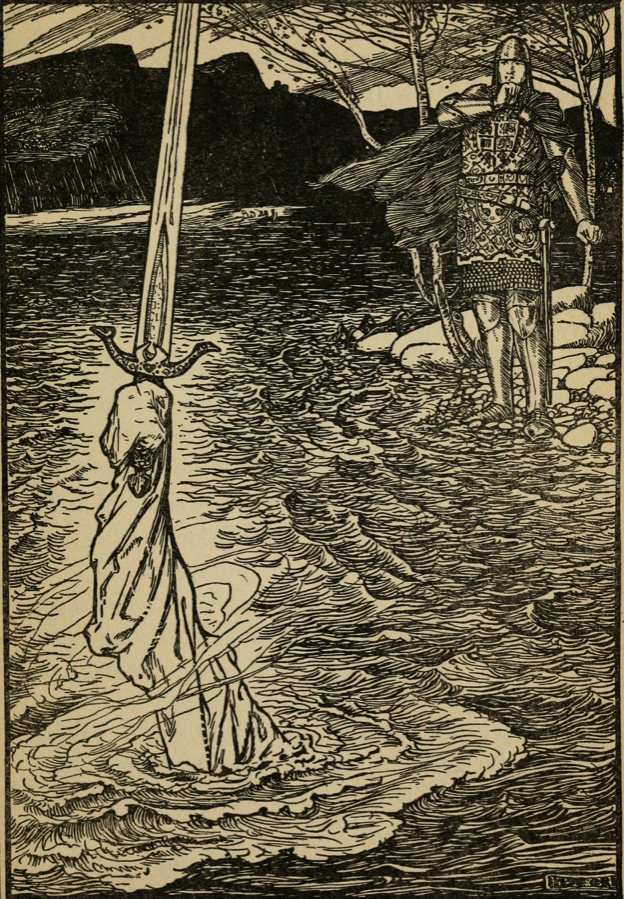

Farther away from the shore, clinging to the rocky sides of the island, the remains of a defended wharf have been discovered. This is known as the ‘Iron Gate’, and up the slope from this are the remains of Dark Age houses where huge amounts of broken pottery have been discovered, as well as Roman glass.

One cannot, however, speak of Tintagel castle and not think of the Arthurian legend. This is why most people visit Tintagel. As the supposed birthplace of King Arthur, as told by Geoffrey of Monmouth, it has an inescapable draw.

But what was here during the Dark Ages, that period between the departure of the Romans from Britain and the invasion of the Saxons.

Several Dark Age ruins have been discovered in excavations over the years on Tintagel rock, including the houses near the defended wharf, and a cluster of buildings on the northern end of the plateau overlooking the sea. However, as only 5% of Tintagel has been excavated, who knows what else remains to be found.

The summit plateau of Tintagel Castle

There is another problem however…

Erosion.

Over the centuries, Tintagel rock has been deteriorating due to weathering, and it is believed that some of the ruins from various periods of its habitation, including the Dark Ages, have fallen into the sea to be lost forever.

From what has been found and studied, however, what might the possible uses been? What was happening at Tintagel castle?

An early theory put forward by Dr. Ralegh Radford, who excavated the site in the 1930s, was that Tintagel was an early monastic settlement, perhaps established by St. Julian or St. Juliot one of the sons of the Dark Age Welsh king, Brychan, in the 5th century.

However, more recently, new theories have dismissed Radford’s monastic theory in favour of one that says Tintagel castle was the settlement of Dumnonia’s elite, the home of a king or ruler of some sort, as well as his entourage and war-band.

Artist impression of Dark Age Tintagel Castle (English Heritage)

This is supported by the pottery finds dating to the period and coming from places like North Africa and Greece which were still a part of the Roman Empire at that time. These luxury items – mainly wine, olives and olive oil – meant that a person of wealth with connections to Rome may have lived at Tintagel. Even if much of the rest of Britain had lost contact with the former Empire during the Dark Ages, Tintagel castle seems to have maintained ties.

With the discovery in 2016 of several Dark Age houses containing Mediterranean pottery and glass, and the finding in 2017 of a slate window ledge with Latin, Greek and Celtic writing, which dated to the 7th century A.D., it seems that Tintagel castle remained a busy and important place.

The ‘Artognou’ slate found at Tintagel Castle

In 1998 however, one of the most tantalizing artifacts to be found at Tintagel was a piece of slate with the name of ‘Artognou’ written upon it. As ever, the story of Tintagel castle comes back to its connection with Arthur.

And why not? Arthur is a powerful draw, a hero at the heart of Britain’s mythology and history.

Adam exploring the ruins of Tintagel Castle on a windswept day in February

As someone who has always loved tales of King Arthur and the Knights of the Round Table, and who has focussed on Arthurian studies for most of his academic career, the Arthurian connection is what brought me to Tintagel in the first place as well.

For years, I had been dreaming of visiting this dramatic location where Merlin was supposed to have helped Uther Pendragon reach Igraine and conceive the once and future king of Britain.

When the opportunity to visit finally came, I jumped at the chance.

What was it like to finally arrive at Tintagel castle?

It was magical.

Postern gate approach to Tintagel Castle from cliffside

While living in Somerset, I decided to take a trip to Cornwall – a sort of Arthurian pilgrimage – during a rainy February. The landscape was no less dramatic than I had imagined, and there were very few tourists around.

In our car, we headed west from Exeter, skirting the northern edge of Dartmoor in the direction of Bodmin, the same as my Roman protagonist in the story.

Even then, the seeds of The Stolen Throne were bound to take subconscious root.

Driving through the landscape really was like driving through another world, especially when it came to Bodmin moor. We arrived at the village of Tintagel, checked into our B&B and went out straight away to find our destination.

The village of Tintagel on the mainland, with King Arthur’s Great Halls on the right.

It was strange walking there from the village, anticipatory and dreamy with the misty rain falling all around us. To our right, the lonely silhouette of the Camelot Castle Hotel stood silent sentry on the approach, at that time seemingly deserted.

There were very few people or cars around as we walked along Castle Road, the sound of the sea becoming more audible and then, there it was – Tintagel’s castle rock.

Interior ruins of Tintagel Castle

I had waited so long to see that place, I simply stood there staring at its beauty, its mythological wildness. What a setting! At that time, Lucius Metellus Anguis (my protagonist) was still in Africa and Rome (I had only written Children of Apollo at that point) but I knew that he would, someday, make his way there.

As we approached the castle, we decided to go down to the Haven first, led there by Castle Road and the Southwest Coastal footpath. From the beach we looked up at Tintagel Castle in awe. To attack the place would be sheer madness, but to live there perhaps more so.

Merlin’s Cave and the ‘Haven’ below Tintagel Castle

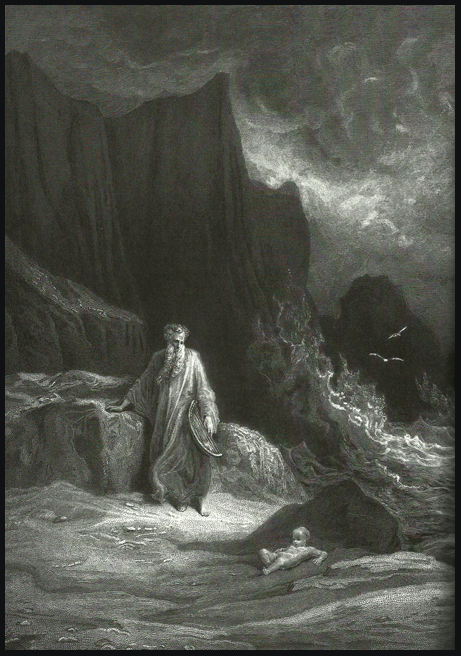

The sea was not calm, nor was it violent, but as we walked across the beach the gaping maw of Merlin’s Cave opened before us and the myths came alive at once.

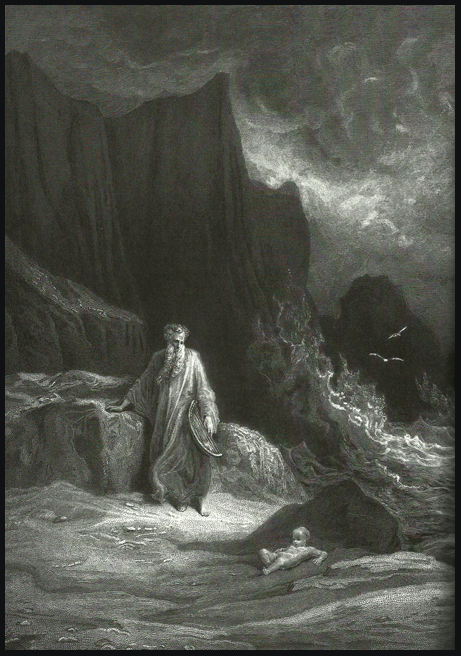

I stood on that beach remembering the image I had seen of Merlin standing upon that beach with the baby Arthur at his feet.

Merlin finds Arthur (by Gustave Dore)

Now, I do believe there was a historical ‘Arthur’, but I also know that the history has been mythologized perhaps more than any other tale in western literature. However, as I stood there upon the beach, Merlin’s Cave before me, and the ruins of Tintagel Castle looming above my head, the line between history and legend definitely began to blur.

It was a magnificent feeling.

Sometimes, we need to let go of our thinking, to step out of the academic realm in order to feel, and in doing so, we experience history more fully, for tales were as much a part of our ancestors’ beliefs as fact, if not more so. They were facts!

Why did Earl Richard build the medieval castle in such an inconvenient place? Perhaps he too wanted to be a part of the myth and history that clung to the cliffs of Tintagel, to be close to Arthur and Merlin, to Mark, Tristan and Isolde…

Ruins of the medieval chapel at Tintagel Castle

The tide started come in and we were caught off guard by the water on the beach. Making a quick escape, we retreated from the Haven and began making our way up to the narrow entrance that gives Tintagel its name, to cross the bridge that soars over the chasm below.

We lingered in Tintagel’s most recognizable ruins for a time, the area of the medieval court and hall before carrying on along the path that wound its way up to the summit plateau, passing the remains of the Dark Age houses on the eastern slope above the Iron Gate’s wharf.

Outline of cliffside structures or houses dating to the Dark Ages on Tintagel rock

Once we reached the top, we were met with a broad, windswept expanse of green beneath an iron grey sky. We wandered around the northern ruins, remnants of the Dark Ages, and then took in the medieval chapel, garden, and tunnel.

But, at Tintagel, for me, it is the setting that is king, the story behind it all. As I stood in the middle of the plateau with my wife, taking in the site, the symphony of sound that was performed by the waves, wind and crying gulls, I let the place seep into me.

I’ve had few experiences like that, though I have been to many places.

In my mind, and in my writing in some way, shape or form, I’ve been back to Tintagel Castle many times since that moment when I stood in the middle of the summit plateau, near the spot where ancient kings of Dumnonia were crowned.

Remains of the medieval walled garden on Tintagel Castle

I felt something of what it was like to complete a pilgrimage. And that is what it was to me. History, myth and legend are, in a way, my own private religion.

Leaving the castle rock of Tintagel behind as we walked back to the village to immerse ourselves in the Arthuriana of King Arthur’s Great Halls, I didn’t feel the usual bittersweetness of leaving a place behind.

As we walked, I turned to look back one more time at Tintagel Castle and felt…well…complete.

Would that we could all feel so complete on our journey through the dark wood of this life.

Tintagel on the Cornish Coast (by William Trost Richards, 1879)

When it came time to write The Stolen Throne, my time at Tintagel flowed into the story as if I had visited only yesterday. I could not have imagined any other setting for that part of the Eagles and Dragons series.

Will my Roman protagonist ever return there? That remains to be seen, but in the annals of my mind, I shall return there often.

Thank you for reading.

The Stolen Throne is now available in e-book and paperback from all major on-line retailers. If you haven’t read any books in the Eagles and Dragons series yet, you can start with the #1 bestselling A Dragon among the Eagles for just 0.99! Or get the first prequel novel, The Dragon: Genesis, for FREE by signing-up for the newsletter HERE.