Welcome back to The World of The Stolen Throne.

Last week, in Part II, we looked at the Roman presence in Cornwall and the few remains that have been discovered. If you missed that post, you can read it HERE.

In Part III, we are going to leave the world of Rome behind to explore the more mysterious past of ancient Cornwall – the Arthurian past.

The Stolen Throne, in a way, is a book of three worlds. It explores two of my own passions as an author and historian: Roman history, and Arthurian studies.

In fact, the novel and its setting was greatly influenced by Arthurian sites in Cornwall, as well as by Celtic mythology.

In this short post, we’ll be taking a brief look at some of the Arthurian sites in Cornwall that inspired some of the settings in this latest Eagles and Dragons novel.

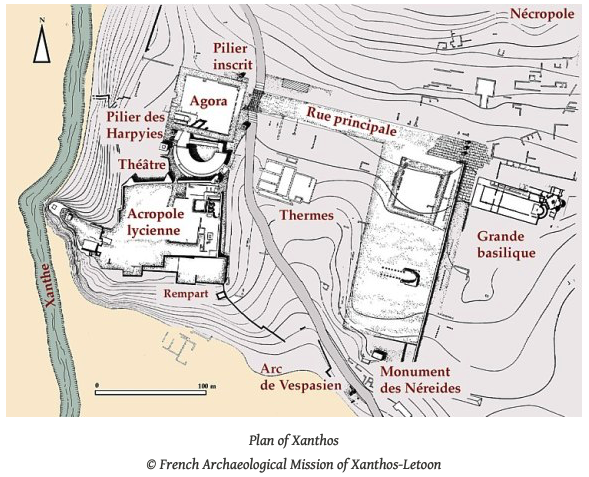

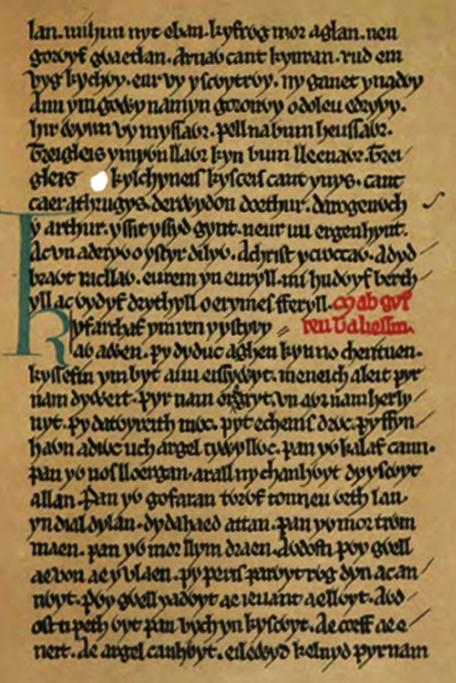

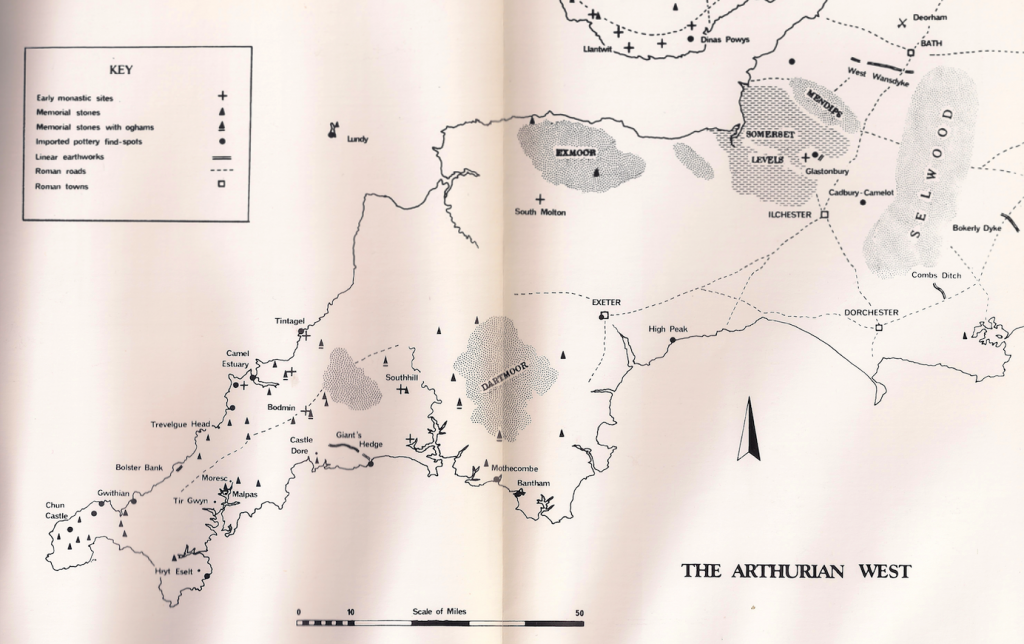

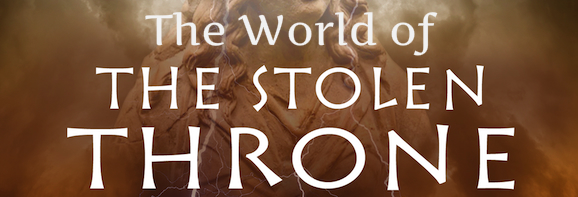

Map from Arthurian Sites in the West (C. A. R. Radford and M. J. Swanton, University of Exeter Press, 1975)

My own love of Arthurian studies has been with me from the beginning. It captured my imagination as a child in the form of stories, and was the focus of my academic studies in later years.

Just as the land of Dumnonia (Cornwall) is a sort of liminal space in The Stolen Throne, the Dark Ages, or Arthurian period is, to me, a liminal space and time between the Classical and Medieval eras.

Some years ago, before moving back to Canada from Britain, I had the opportunity one rainy February to tour Cornwall for the first time. This was more than just a nice trip for me, it was a pilgrimage of sorts. I had dreamt of visiting several Arthurian sites in Cornwall for years, and when the chance came to do so, I jumped at it.

Roughtor, Bodmin Moor aerial view (photo: webbaviation.co.uk)

It was wintry and crisp when we left Somerset and drove through Devon that February, skirting the northern edge of Dartmoor and heading deeper into Dumnonia, just as the protagonists in The Stolen Throne did, leaving the world of Rome and Isca Dumnoniorum behind.

Cornwall was different, mild and misty. Rain began to fall and did not stop, and the landscape was like no other I had seen before.

The land cast a spell over me.

Cornwall is covered in ‘Arthurian’ sites, including early monastic settlements, memorial stones, earthworks and more, but the sites I wanted to visit most were concentrated on that wondrous landscape of Bodmin Moor, a place of grassland and downs where the horizon is pierced by rocky tors, formations that make it a world unto itself.

Rock formations on Stowe’s Hill – Granite tors on Bodmin Moor (photo: Gareth James)

Arthur is a part of the landscape here, of its historical and mythological DNA, with places named Arthur’s Chair, and Arthur’s Oven, or Arthur’s Bed. For an Arthurian enthusiast, Cornwall is one vast adventure or hunt upon the windswept moors.

One of the first places we sought was none other than Dozmary Pool.

Approach to Dozmary Pool

Dozmary Pool is one of the places in Arthurian tradition that is associated with Excalibur.

It is a tarn (a mountain lake) 900 feet above sea level, in the middle of Bodmin moor. Where it sits, surrounded by open grassland and hills, Dozary Pool is, perhaps, one of the most mysterious places I have ever been too.

No doubt that is due to the tales it has been cloaked in over the centuries. Local lore, for a long time, said that the pool was bottomless, until it dried up in 1859, but the place continued to be a place of mystery.

And you can feel it.

To the ancient Celts, pools were often sacred, the water spirits who watched over them to be respected, and feared. Offerings, sometimes in the form of weapons, were made at such pools.

There was one such offering that I had in mind as I parked my car and took the footpath to the shore of Dozmary Pool…

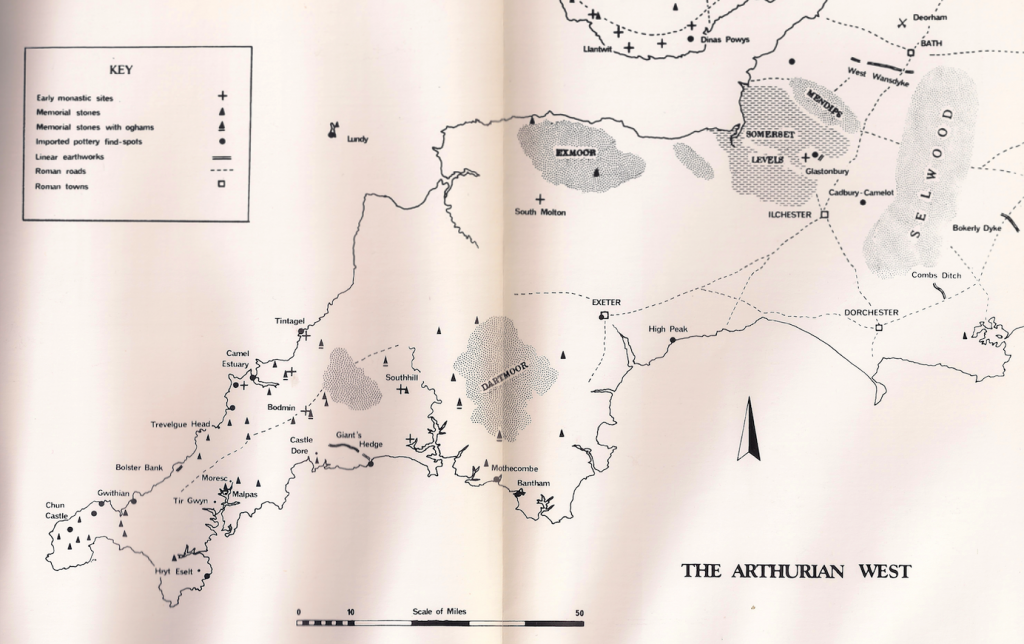

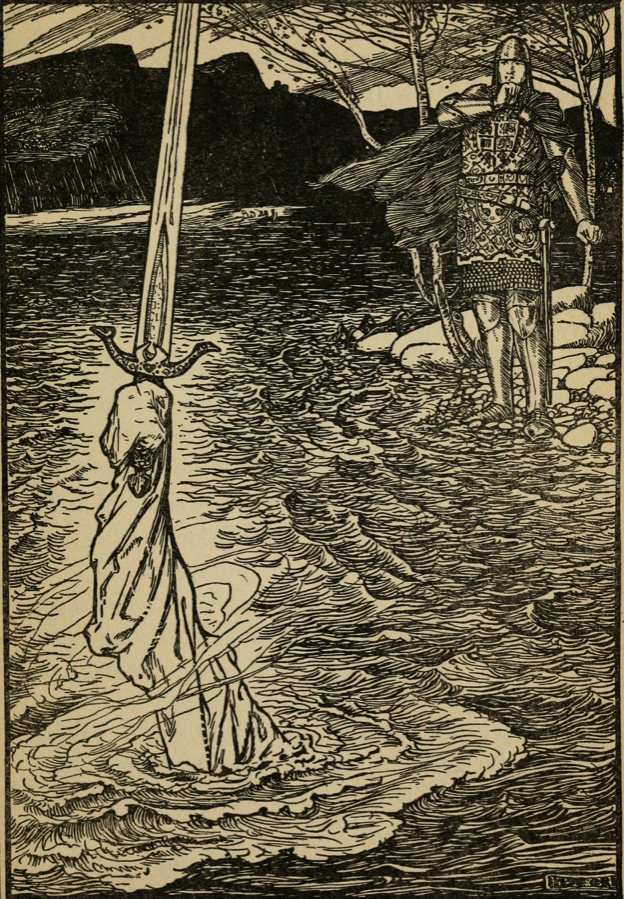

In Arthurian legend, at the end of the cycle, after the bloody battle of Camlann where Arthur receives his fatal wound, Sir Bedivere, at Arthur’s bidding, takes the sword Excalibur and throws it (after two attempts) into a body of water to return it to the Lady of the Lake.

In the ancient land of Dumnonia, Dozmary Pool is that lake.

Whether the story is true or not, as I approached the calm water of Dozmary Pool, I felt the spell of myth and legend grab hold of me in a way that I had never before experienced. I stood there, playing the scene over and over again in my head, of a battle-worn warrior standing at the edge of the water with his fallen king’s sword in his hand, gathering the courage to offer up Excalibur to the dark depths before him.

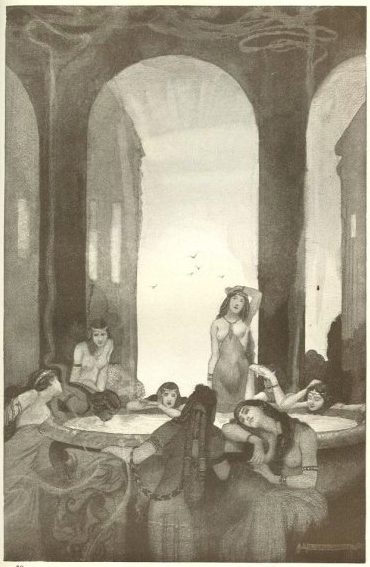

Sir Bedivere returns Excalibur to the lake (Andrew Lang, 1908)

Even as the rain beat down on me, I felt a sense of calm in that place as my eyes scanned the rippling surface and the line of the shore with the hills rising in the distance.

It was a lonely and beautiful place.

After some time, I turned to pull myself away, to carry on with my journey, and was met by a curious monster-of-a-horse (perhaps a shire or sport horse?) towering over me, seeming to stare down at me wondering what I was up to. I looked up at him, and reached to touch his neck. He leaned into me as I took one last look at the sacred pool spread out before us.

Dozmary Pool on Bodmin Moor, Cornwall

It was not easy to leave Dozmary Pool or my new friend behind, but there were other places to visit on my Arthurian pilgrimage. I walked back up the footpath where rain cascaded down and around me toward the pool. I turned again, one more time, to glimpse the water before getting in the car and driving away.

The next destination we sought could only be reached by a circuitous, 19 mile route across Bodmin, but it was one that I had longed to see for years.

It wasn’t a place where any great scene from Arthurian legend had taken place, such as at Dozmary Pool. However, from the images I had seen over the years, the setting called to me, as did the name of Arthur’s Hunting Lodge.

Arthur’s Hunting Lodge with remains of stone wall slabs visible

Also known as Arthur’s Hall, Arthur’s Hunting Lodge is a stone enclosure on Bodmin Moor near to Mount Pleasant, Garrow Tor, and Hawks Tor.

To visit this site, you need to park the car near St. Breward and take a foot path across the moor for a short distance.

The walk is magnificent.

This section of Bodmin Moor is crossed by an ancient highway dotted with markers in the form of short standing stones. As you walk, across it, there is a sort of thrumming in the air, just beneath the sound of the wind. It feels like history is speaking to you.

Standing stone on ancient trackway across Bodmin Moor

The setting for Arthur’s Hunting Lodge is magical, and the site itself fascinating.

Set in the middle of the moor, this rectangular structure has walls that are formed by great slabs of granite jutting out of the grass and moss-covered earth. It is 60 feet long and about 35 feet wide. The floor of the ‘lodge’ is also lined with granite slabs.

It is believed to have prehistoric origins, but was used over the centuries as a shelter or as a water reservoir upon the moor.

There are many similar sites associated with Arthur across Britain. Some may have links to the historical Arthur, and many may be the stuff of legend.

However, standing among the ruins of this ancient site, I could see how this ancient association with Britain’s greatest hero, in a land long-tied to him, could grab hold of the imagination.

Adam exploring Arthur’s ‘Hunting Lodge’ on Bodmin Moor

As the wind sang all around me in that isolated place, I could begin to see Arthur and his men resting here while hunting deer on the surrounding moorlands.

It is a place where one can leave the cares of the world behind.

And I can understand that…

How many times have you visited an ancient site and wished you could remain there in calm, comfortable silence with the past?

Arthur’s Hunting Lodge, for me, was such a place.

But as I stood beside the leaning stone slabs of the walls of the lodge, and looked to the rise in the land to the north called Arthur’s Downs, I knew I could not stay.

What I did not know is that one of the most poignant scenes in The Stolen Throne would later be set in that place.

Arthur’s Hunting Lodge on Bodmin Moor

The fight began and immense slaughter was done on both sides. The loses were greater in Mordred’s army and they forced him to fly once more in shame from the battlefield. He made no arrangements whatsoever for the burial of his dead, but fled as fast as ship could carry him, and made his way towards Cornwall.

Arthur was filled with great mental anguish by the fact that Mordred had escaped him so often. Without losing a moment, he followed him to that same locality, reaching the River Camblan, where Mordred was awaiting his arrival…

It is heartrending to describe what slaughter was inflicted on both sides, how the dying groaned, and how great was the fury of those attacking. Everywhere men were receiving wounds themselves or inflicting them, dying or dealing out death…

They [Arthur’s forces] hacked a way through with their swords and Arthur continued to advance, inflicting terrible slaughter as he went. It was at this point that the accursed traitor [Mordred] was killed and many thousands of his men with him…

Arthur himself, our renowned King, was mortally w0unded and was carried off to the Isle of Avalon, so that his wounds might be attended to. (Geoffrey of Monmouth, History of the Kings of Britain, xi,2)

Like many ancient myths and legends, the end of the Arthurian cycle is one of tragedy.

No matter how many times I read stories about Arthur and his knights, even though I know how it ends, I always hope that things will go differently, that Arthur will win out against the odds, that might will truly remain on the site of right.

But the story is a tragedy, and that is why a part of me approached the next site on our itinerary with some trepidation.

Ten miles to the north of Arthur’s Hunting Lodge lies Slaughterbridge, one of the possible sites of the Battle of Camlann, Arthur’s last battle.

Field at Slaughterbridge, possible site of the Battle of Camlann, with Bodmin Moor beyond

It is difficult to explain to someone how a story linked to a place for so long can affect you so deeply, even though the connection may be disputed.

However, when I say that I felt a great sadness approaching the field of Camlann at Slaughterbridge, know that I am serious.

Slaughterbridge and the battlefield of Camlann are located at a crossing over the river Camel, near the village of Camelford.

After passing through the small Arthurian centre that is on site, you come onto a broad meadow that is thought to be the site of the early sixth century battle of Camlann. As I was there in February, no one else was present, and so I could roam about that dread place at my leisure, allowing it to sink into me.

The River Camel where it runs through Slaughterbridge

When John Leland, the Tudor antiquarian, visited here in the sixteenth century, he was told by locals that pieces of armour, rings, and brass horse harness were often found around the site.

Archaeologists in more recent years have found no such things, but there is one artifact at Slaughterbridge that ties the site to the Arthurian period.

As you walk down the slope of the hill toward the trees, you come to the river Camel where it is hidden at the bottom of a small valley.

The screams of the dead and dying men at Camlann, where the water is supposed to have turned red with their blood, have been replaced by an eerie silence. However, when you stand upon the wooden platform looking down on the gurgling river below, you can see the nine foot long ‘Arthur Stone’, a commemoration of the Battle of Camlann.

The River Camel at Slaughterbridge with the ‘King Arthur Stone’ at the bottom left

This is an interesting artifact for upon it is a Latin inscription commemorating one Latinus, son of Magarus.

The stone is not in situ, but was moved here from nearby, long ago. At one point, a confused translation led others to believe that the inscription was dedicated to ‘Atry’, or ‘Arthur’.

Though the inscription may cause confusion, the stone does indeed date to the approximate time of the Battle of Camlann, circa A.D. 537.

The Battle between Arthur and Mordred (by William Hatherell)

As I made my way across the deep green meadow of Camlann toward the dark trees that shielded the river from the world, I could see and hear the grisly sounds of Arthur’s last battle. The cries of dying men and horses filled my mind, perhaps as it did for Geoffrey of Monmouth, John Leland, Richard Carew, and later Alfred Tennyson, when they too came to that battlefield in their own times.

Did Arthur and Mordred fight their final battle here at Slaughterbridge? Was this the site of that fateful Battle of Camlann?

We will never know for certain, but for so long this place has been linked to Arthur’s end, has formed the setting for that end, that you cannot help but feel a great sadness standing there, looking down at the flowing water beneath the dark trees, and staring at the sad memorial stone of a long-dead warrior.

The Death of King Arthur (John Garrick, 1862)

Like the other sites I had visited on my Arthurian pilgrimage in Cornwall, this place too would play a role in The Stolen Throne. The water of the river Camel is that liminal space where Lucius Metellus Anguis finds himself taken, a place where everything changes…

In a way, I am still haunted by my visit to Slaughterbridge.

As I left the battlefield behind, I knew I had had my fill of that bleeding piece of earth, the trees, and the water that had once run in crimson rivulets.

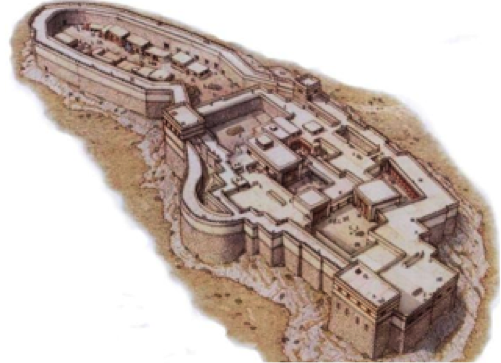

I turned toward the last of my destinations on that journey, the place where Arthur was supposed to have come into the world at the beginning of his life… I turned with hope toward Tintagel Castle.

Stay tuned for Part IV in The World of the Stolen Throne when we will look at the history, archaeology and legend of one of the main settings in The Stolen Throne – Tintagel Castle.

The Stolen Throne is now available in e-book and paperback from all major on-line retailers. If you haven’t read any books in the Eagles and Dragons series yet, you can start with the #1 bestselling A Dragon among the Eagles for just 0.99! Or get the first prequel novel, The Dragon: Genesis, for FREE by signing-up for the newsletter HERE.