Salvete history-lovers!

Welcome back for the second part in The World of the Blood Road in which we are taking a brief look at the people, places and history involved in the research for this newest Eagles and Dragons novel.

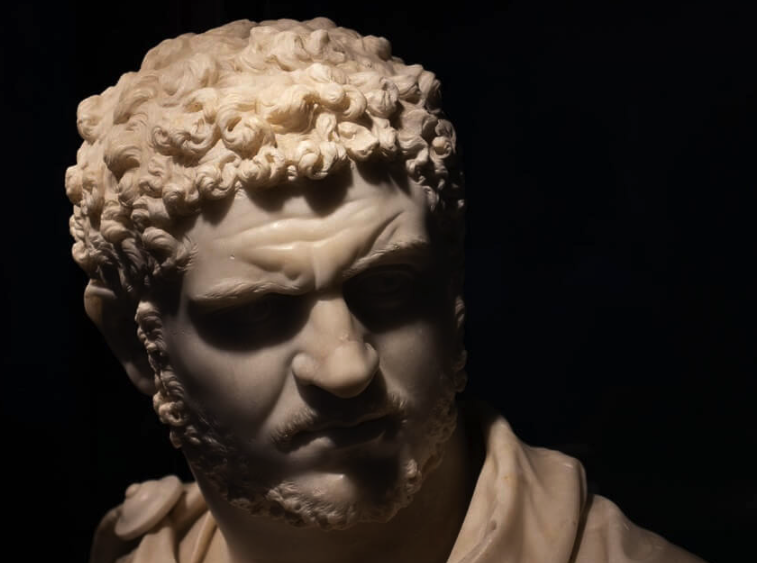

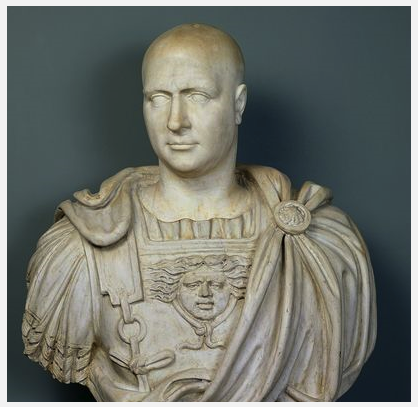

In Part I, we looked at Emperor Caracalla and the murder and fratricide that marked the beginning of his reign. If you missed that post, you can read it by clicking HERE.

In Part II, we’re going to be taking a brief look at travel and transportation in the Roman Empire. As we shall see, this is something the Romans did really well!

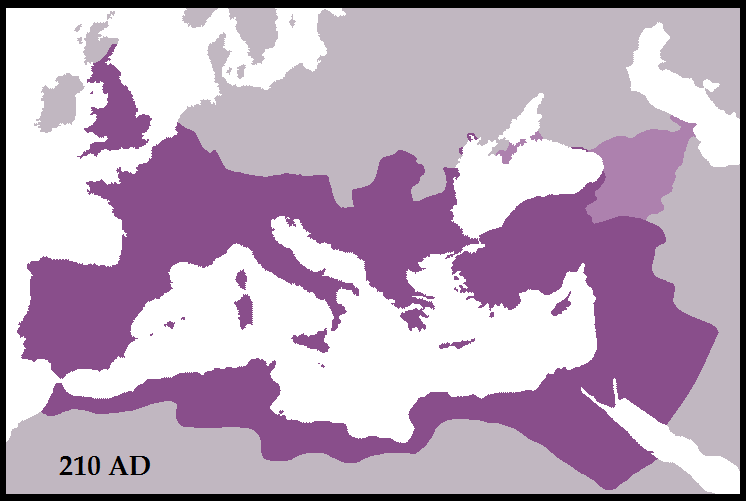

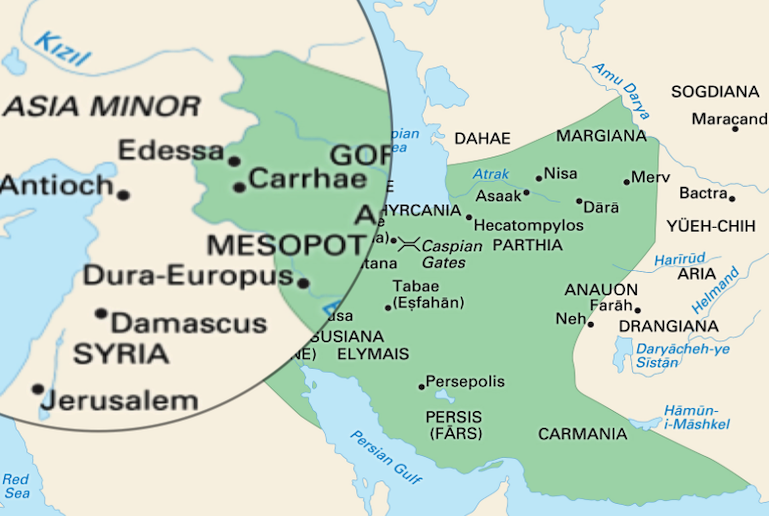

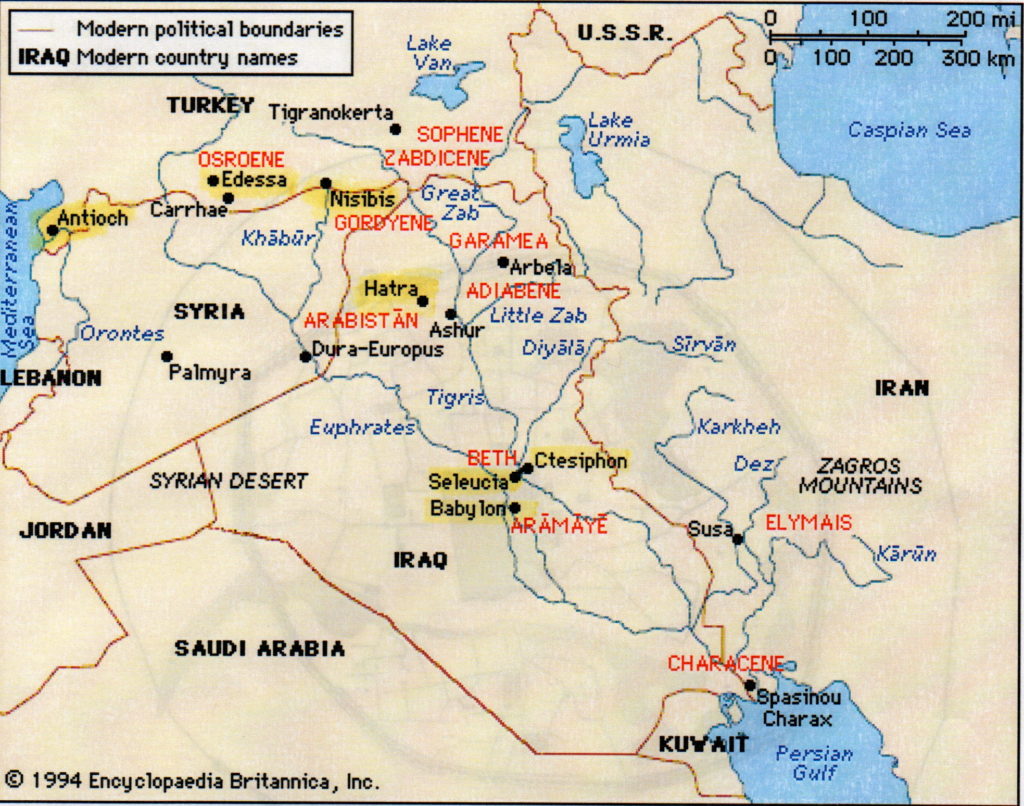

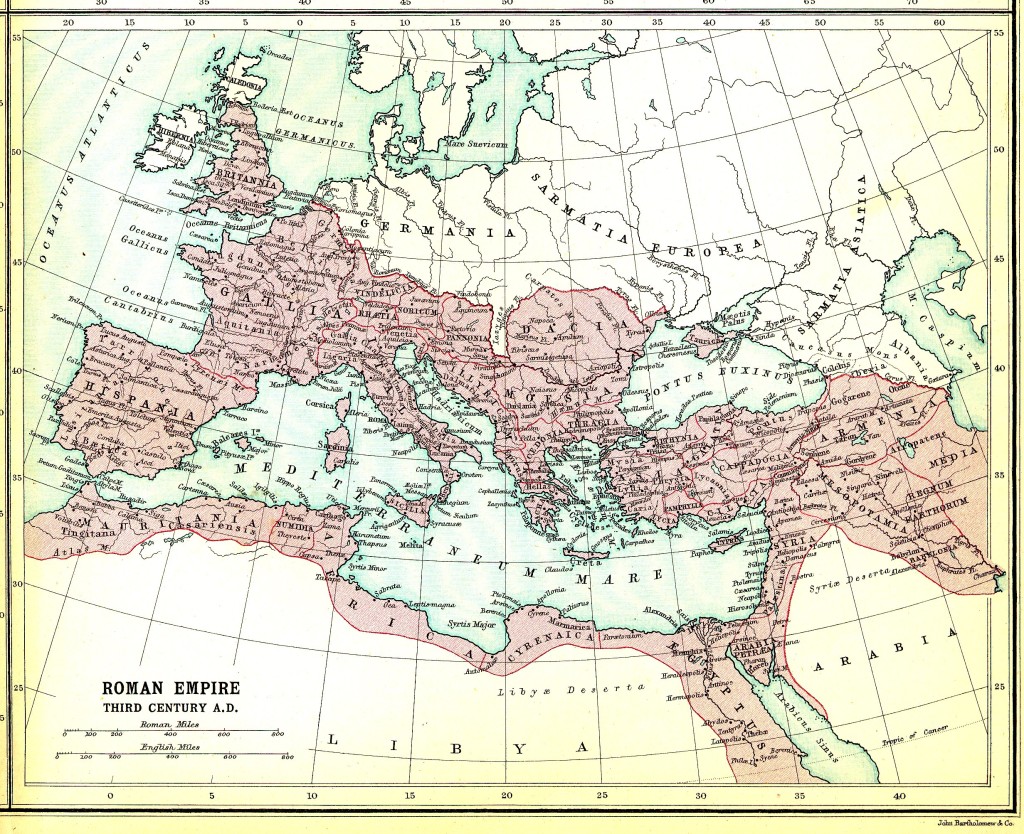

The Blood Road is an epic story that spans the Roman Empire from Britannia all the way to Parthia in the East. Travel is, naturally, a part of the story.

However, travel is something that we take for granted today. We decide we need to get somewhere, and we just go, be it nearby, or over a great distance across the ocean. We often take it for granted in fiction too; characters often need to get from point A to point B, and it happens.

But in the ancient world, travel wasn’t so easy. It required planning, and it took time.

There were also many factors involved such as destination, budget (not unlike today), mode of transportation, and time of year. Unless one was a soldier, or merchant, or someone wealthy, chances are that you might never have left your community.

So, when people did travel in the Roman Empire, how and why did they do so?

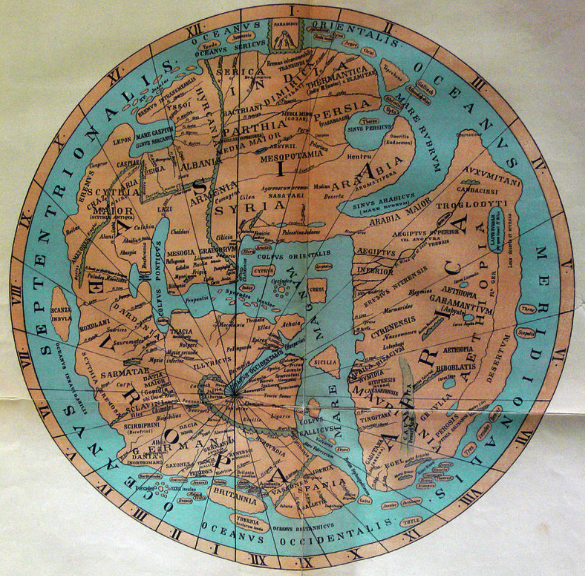

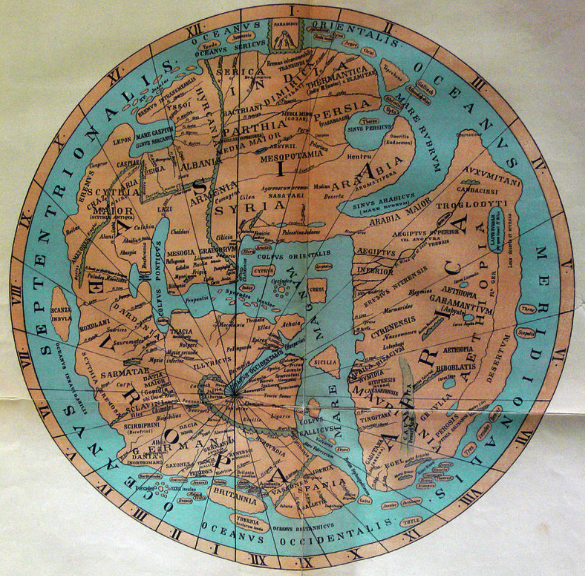

Ptolemy’s world map, reconstituted from Ptolemy’s Geography, circa AD 150, in the 15th century, indicating Sinae, China, at the extreme right. (Wikimedia Commons)

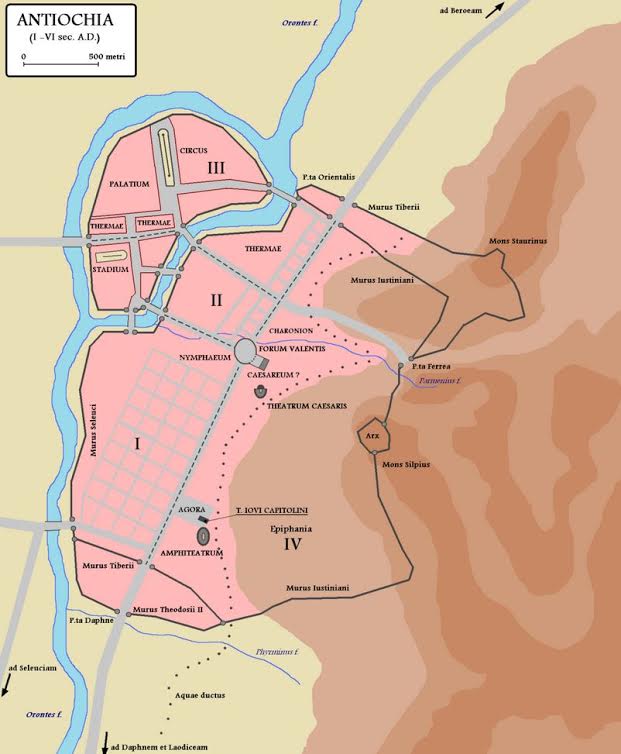

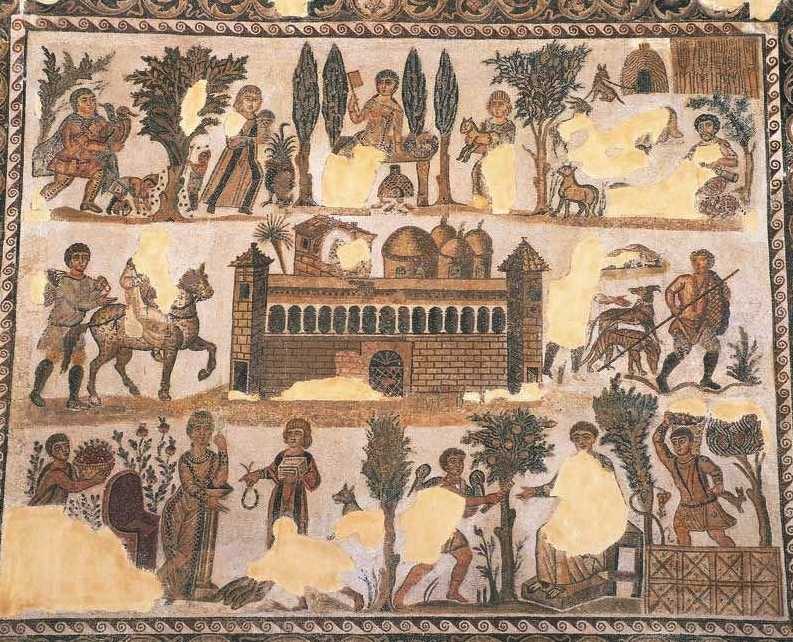

First off, we should probably discuss maps. We use maps today, and the Romans had maps. Geography was important, especially if you were planning a large scale invasion or military campaign, or even surveying for a new settlement. Not many maps from the Roman period survive, but copies of maps were made from originals. Sometime they were even rendered in paintings or mosaics.

Maps, geography and cartography are mentioned by some ancient authors such as Strabo, Polybius, Pliny the Elder, and Ptolemy. We also know that large wall maps of the world were commissioned by Julius Caesar, and then by Agrippa, during the reign of Augustus.

Much of our knowledge of place names and geography from the Roman world comes from what are called ittinerarium pictum, or ‘iteneraries’, which were travel itineraries accompanied by paintings. Perhaps the most well-known of these is Ptolemy’s Geography which included six books of place names with coordinates from around the Empire, including faraway places such as Ireland and Africa.

Another source is the Ravenna Cosmography. This was a compilation by an 11th century monk of documents dating to the 5th century A.D. It was made up of copies by a cleric at Ravenna, dating to around A.D. 700. This particular source gives lists of stations, river names and some topographical details.

Details of a map based on the 11th century Ravenna Cosmography (Wikimedia Commons)

The Notitia Dignitatum is a late Roman collection of administrative information which included lists of civilian and military office holders, military units and forts. The maps that accompanied this were medieval, but it is believed that they were derived from Roman originals of the fourth and fifth centuries A.D.

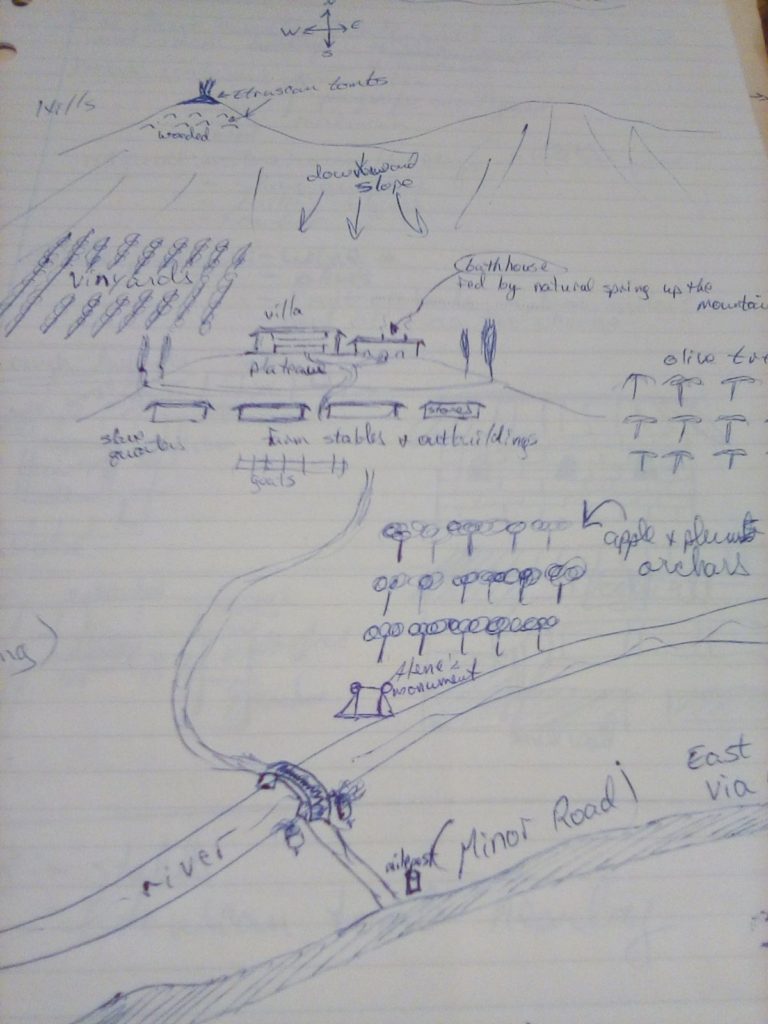

Perhaps the most important surviving example of an itinerary, however, is the Itinerarium Antoninianum, the ‘Antonine Itinerary’, which was a collection of journeys compiled over seventy-five years or more and assembled in the late 3rd century. It describes 225 routes and gives the distances between places that are mentioned. Some believe it was probably used for travel by emperors or troops. This particular source also included a maritime section with sea routes entitled Imperatoris Antonini Augusti itinerarium maritimum. The longest route in this itinerary appears to represent Caracalla’s trip from Rome to Egypt in about A.D 214-215, the exact time period for The Blood Road.

Map of Roman Britain based on the Antonine Itinerary, plotted by William Stukeley in the 1700s using the Itinerary as its source. (University of Kent)

Next, one cannot talk about travel in the Roman Empire without talking about one thing in particular: Roads.

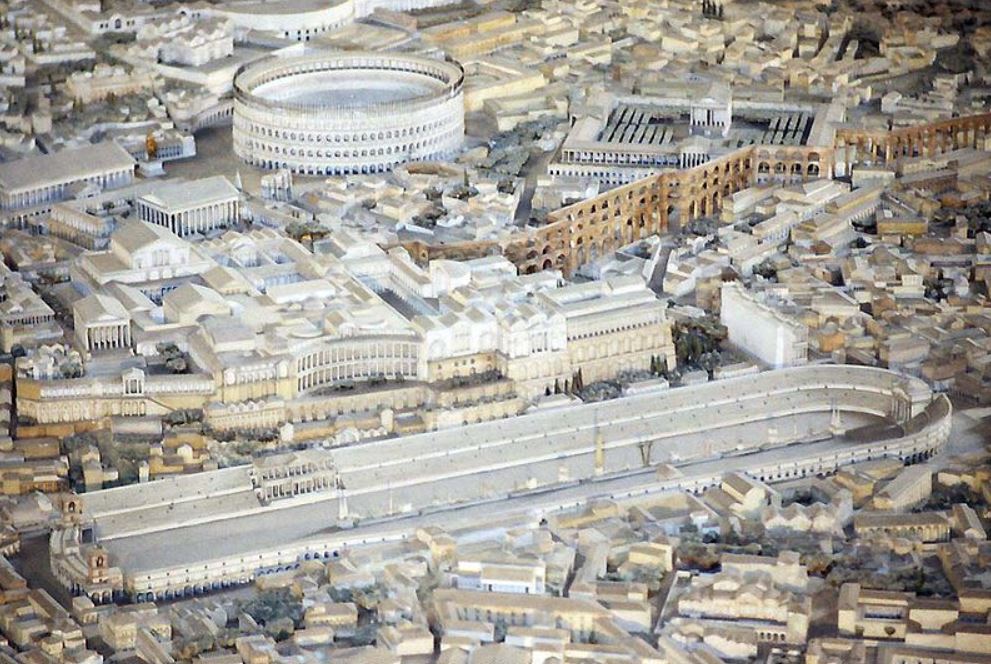

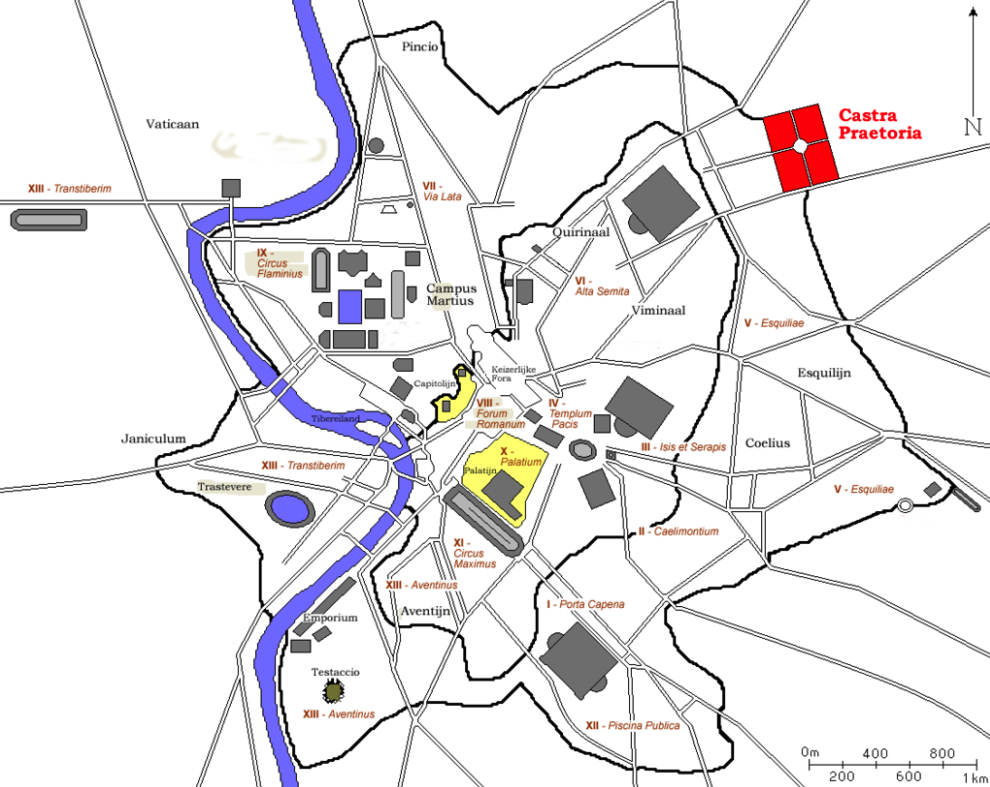

There is a reason the expression ‘All roads lead to Rome’ exists. It was true, at least for a time. This is believed to have originally referred to the milliarium aureum, the ‘golden milestone’ near the temple of Saturn in the Forum Romanum, from which all distances were measured. It is believed that distances to specific cities or settlements were written upon it.

Roman roads, such as this section of the Fosse Way in Leicestershire, are still in use today. (photo: Geograph.org)

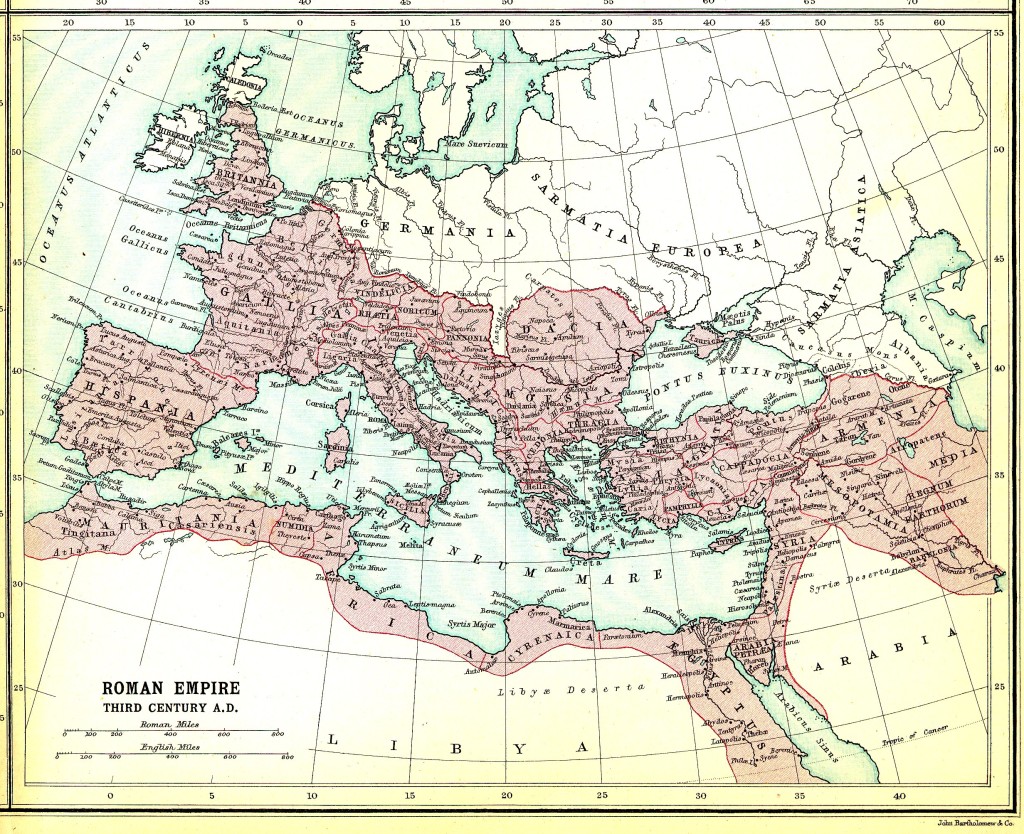

When it comes to roads, Rome was the best. In fact, Roman roads forever altered the empire and travel itself. Not only did Roman roads make troop movements much easier – with the troops building the roads themselves! – but they also opened up parts of the empire to trade and further settlement. They spread out from Rome like a titanic spider web connecting the eternal city to the farthest outposts.

There were also various types of road too, not just the broad, paved roads upon which vehicles and legions could travel. There were also small tracks, causeways, narrow streets, embanked roads or strata, lanes and more. Whether you were crossing the world, or crossing a settlement, roads of all types were useful.

The Roman empire in the time of Hadrian, showing the network of main Roman roads. (Wikimedia Commons)

Of course, with Roman roads, came Roman bridges over rivers that might have added days to a journey in order to reach a suitable crossing point. Travel was shortened in many ways by using Roman roads.

Now that we know how important roads were to the Roman Empire, how did people travel upon them?

When it came to the legions, marching was the order of the day for most troopers, and the average Roman soldier, fully laden, could travel up to 25 Roman miles in one day. For the average person living within the bounds of the Empire, walking was also the norm. This mode of travel was slower, to be sure, though roads made it much easier.

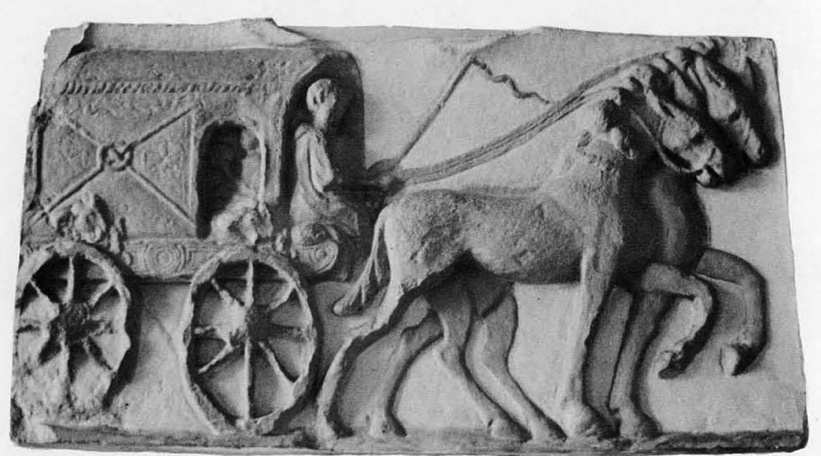

Apart from walking, there were of course other, faster modes of transportation such as by horse, pack animal, two-wheeled cart, and four-wheeled wagon. Obviously, these required one to have the funds to own or rent such animals and vehicles, but they did greatly cut back on the travel time.

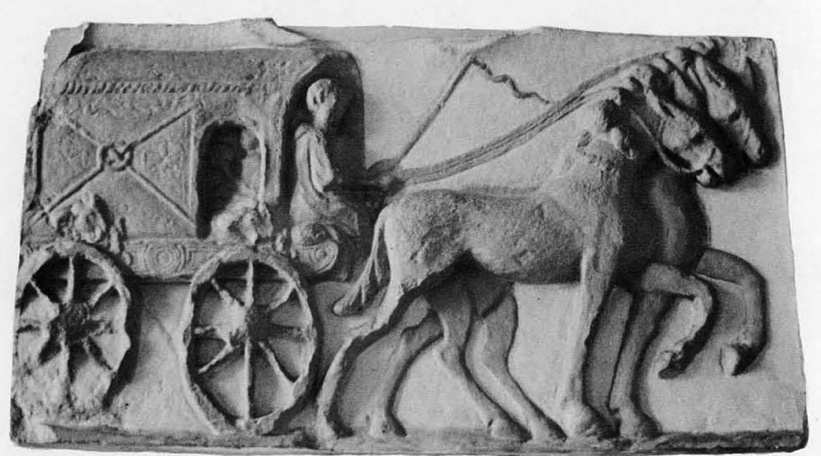

A Roman relief showing a four-wheeled, covered wagon (photo – Penn Museum)

The time of year and the weather were obvious factors when it came to travel upon roads, but also when it came to water routes open to travellers such as by river, open sea, and coastal sea travel.

When it comes to seafaring, the Romans had no such tradition until after the wars with Carthage which forced them to come to terms with the need for a navy. With the creation of that navy, Roman troops could be moved more quickly from Rome to Africa, for instance.

The other reason for travelling by sea or waterway was, perhaps more importantly, trade. The Roman Empire at its peak was vast and varied, and there was an enormous trade network that ensured raw materials such as lead and marble made it to construction sites as far away as Britannia, or from there to Rome itself. Perhaps the officers on Hadrian’s wall missed their favourite garum produced in Hispania, or wine from their family’s Etrurian estate?

A Roman cargo ship, or ‘corbita’ (image: naval-encyclopedia.com)

To transport large amounts of goods where they needed to be at the farthest reaches of the Empire, or to the heart of Rome itself, sea transport was the way to go, and massive ports such as those at Ostia, Carthage, Alexandria, and Piraeus were constantly alive with trade.

There were various types of ships, both commercial and military, but despite the efficiency of this mode of transport, it was even more restricted by the seasons and weather than travel over land. Sea travel could be absolutely treacherous, and the number of ancient shipwrecks that dot the coasts of the former Roman Empire are a testament to this.

The wreck of a 110-foot (35-meter) Roman ship, along with its cargo of 6,000 amphorae, discovered at a depth of around 60m (197 feet) off the coast of Kefalonia. (Photo: CNN)

If you want to read more about the various types of ships used in the Roman Empire, be sure to check out the Naval Encyclopedia page HERE.

As mentioned before, we often take travel for granted in the modern world, but it cannot be overstated how important travel was during the Roman Empire, nor how much Roman road and ship building opened up the world and the economy of Europe at the time. Yet another thing the Romans did for us!

The Port of Ostia, today and in the 2nd century A.D. (photo: BBC/The Portus Project)

I hope you’ve enjoyed this brief post about travel and transportation in the Roman Empire.

If you are interested in taking a look, one particular tool that was especially useful when researching and writing The Blood Road was Orbis: The Stanford Geospatial Network Model of the Roman World. This special GIS tool uses ancient and modern source information to accurately create itineraries for travel between destinations in the Roman Empire, taking into account mode of transport, time of year, and whether travelling by land or sea. You can check that out HERE.

Stay tuned for Part III in The World of The Blood Road in which we will be taking a look at one of the stranger acts of legislation during the reign of Emperor Caracalla: the Constitutio Antoniniana.

Thank you for reading.

The Blood Road is available on-line now in e-book and paperback at major retailers. CLICK HERE to get your copy. You can also purchase a copy directly from Eagles and Dragons Publishing HERE.

If you are new to the Eagles and Dragons historical fantasy series, you can check out the #1 best selling prequel, A Dragon among the Eagles for just 1.99 HERE.