historical fiction

Writing Ancient Religion

Why is it that a lot of writers steer clear of ancient religious practices in fiction?

Is it because it’s awkward and clashes with their modern beliefs, religious or otherwise? Or perhaps it’s because they don’t feel comfortable writing about something so strange, practices they really know very little about?

There is a lot of good fiction set in the ancient world and I’m always trying to find new novels to entertain and transport myself. One thing I’ve noticed is that when it comes to the religious practices of ancient Greeks and Romans, they are often (not always) portrayed as half-hearted, greeted with a good measure of pessimism. It might be a passing nod to a statue of a particular god or goddess, or a comment by the protagonist that he or she was making an offering even though they didn’t think it would do any good.

There is often an undercurrent of non-belief, a lack of mystery.

Now, I’m not full of religious fervour myself; it’s difficult for anyone who has studied history in depth to be so. However, I see the value of it and respect its meaning for people across the ages. Religion is not necessarily at the forefront of our thoughts in modern, western society, but, in the ancient and medieval worlds, faith was often foremost in people’s thoughts.

It’s easy, blinded by hindsight, to dismiss ancient beliefs in the gods and goddesses of our ancestors.

As a writer, why would I want to dismiss something that is so important to the period in which my novels take place, something so important to the thoughts and motives of my characters?

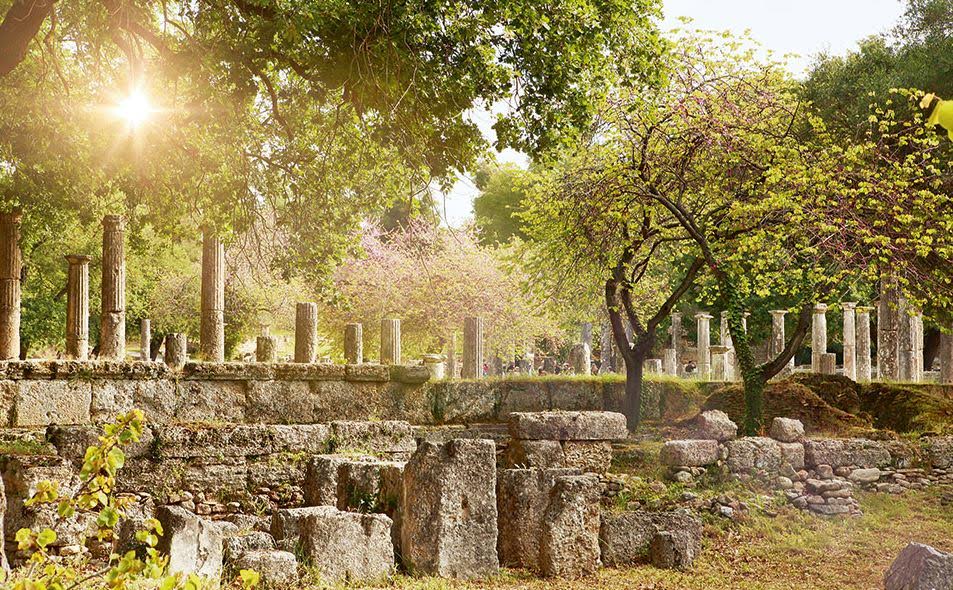

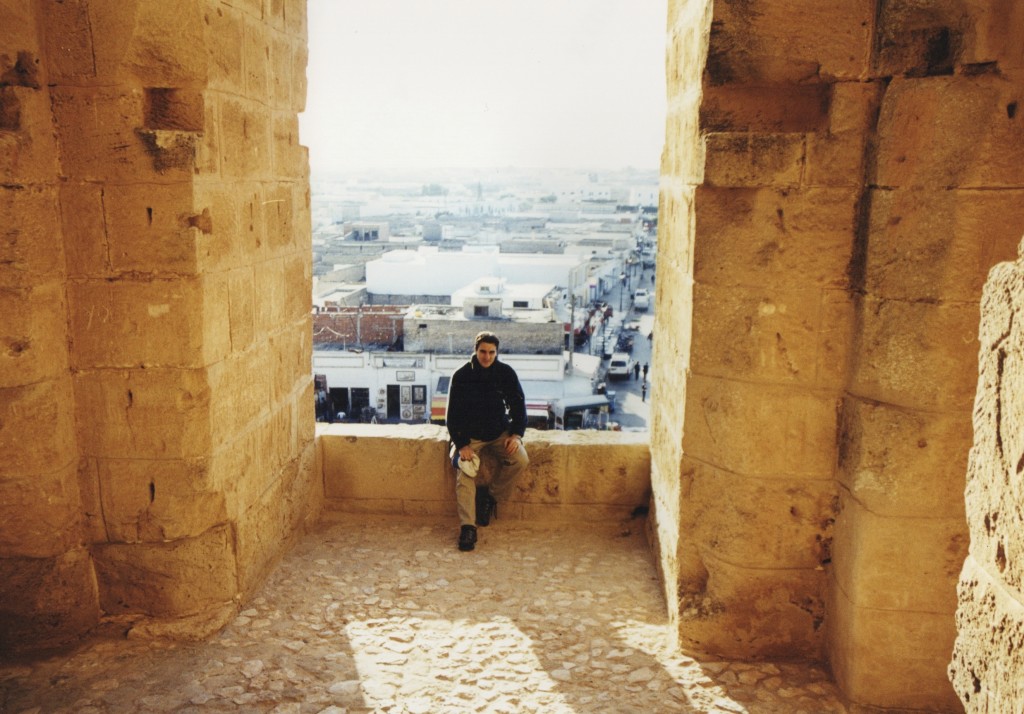

The Door to Hades – part of the sanctuary of Elefsis, where the Elefsinian Mysteries were carried out

People in ancient Greece and Rome (for example) believed in a pantheon of gods and goddesses who governed every aspect of life. From the emotions one felt or the lighting of a family hearth fire, to the start of a business venture or a soldier’s march to battle, most people held their gods and goddesses close. Indeed, there was a god or goddess with accompanying rituals for almost everything.

Religion enriches the ancient world in historical fiction and sets it apart from today, transports the reader to a world that is foreign and exotic. And the beauty is that there is so much mystery, so little known, that the writer can spread his or her creative wings.

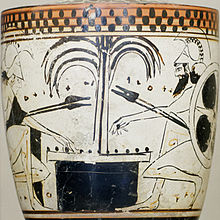

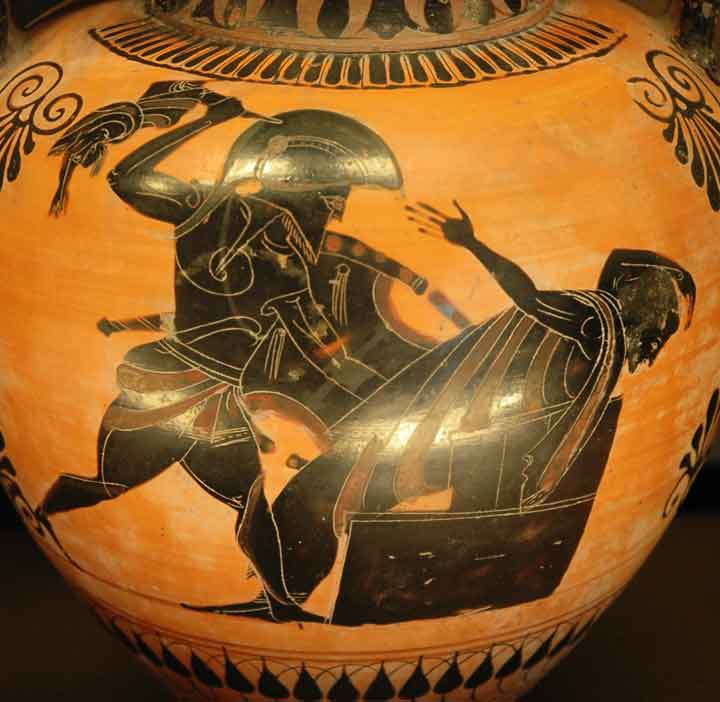

Of course, it’s always important to do as much research as possible – if the primary texts don’t tell you much, then look to the paintings on ceramics, wall frescoes, statues and other carvings. If you can get to the actual sanctuaries of the ancient world, even better, for they are places where even the most sceptical person can feel that there is (or was) indeed something different going on.

When I write, I try to do something different by having my main characters in close touch with the gods of their ancestors. Since it is historical fantasy, I can get that much more creative in having characters interact with the gods who have a clear role to play and are characters themselves.

The beautiful thing about the gods of ancient Greece and Rome is that they are almost human, prone to the same emotions, the same prejudices, that we are. From a certain point of view, they’re more accessible.

Despite this however, their worship, be it Apollo, Venus, Magna Mater, Isis, Jupiter, Mithras or any other, is still shrouded in mystery, clouded by the passage of time. Thousands and thousands of ancient Greeks and Romans flocked to Elefsis to take part in the mysteries dedicated to Demeter and Persephone, but little is known because devotees were sworn to secrecy. Oaths then were ‘water-tight’ as the saying went. Also, at one point, most of the Roman army worshiped Mithras, the Persian Lord of Light and Truth. Do we know much about Mithraism? Some, but there is still much that is not known and perhaps never will be.

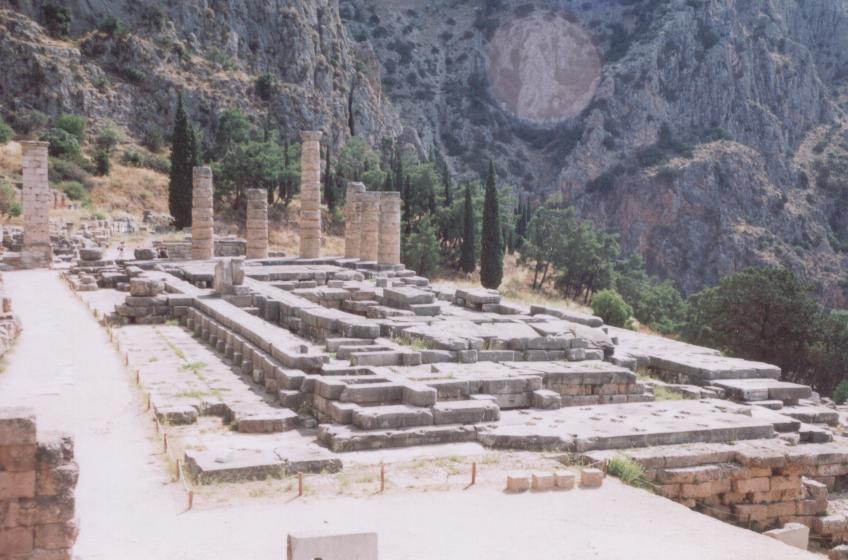

In one of my books some of the characters pay a visit to the Oracle of Apollo at Delphi, which was still revered in the Roman Empire. Today, if you watch a documentary on Delphi, you will hear about how the oracle was used by politicians to deliver fabricated answers to those seeking the god’s advice. It is true that politics and religion in the ancient and medieval worlds were frequent bedfellows, but one can not dismiss the power of belief and inspiration. If the Athenians had not received the famous answer from the Delphic Oracle about being saved by Athens’ ‘wooden walls’, then they might not have had such a crushing naval victory over the Persians at Salamis.

There is a lot of room for debate on this topic and many, I suspect, will feel strongly for or against the exploration of ancient religion in fiction. If we feel inclined to dismiss ancient beliefs, to have our characters belittle them, to explain them away, we must ask ourselves why.

Do we dismiss ancient beliefs because we think they are silly, quaint, barbaric or false? Or do we stay away from them because we just don’t understand? Taking an interest in them, giving them some space on our blank pages, doesn’t mean we dismiss our own beliefs, it just means that we are open-minded and interested in accurately portraying the world about which we are writing.

I like my fiction to be vast and multi-hued. Like the Roman Empire, all gods and goddesses are welcome to be a part of the whole and it is my hope that, being inclusive, my own stories will be more interesting, more true to life, more mysterious.

I suppose, at the end of the day, we each have to decide whether to take that leap of faith.

Thank you for reading.

THANATOS: Death and the Carpathian Interlude

Today I’m very excited to announce that Thanatos, Part III of the Carpathian Interlude, is finally out in the world!

I know this novella has been a long-time-coming, especially for those of you who have e-mailed me to say that this series is your favourite of all my books.

It feels rather strange to finish this trilogy. It’s the end of a journey that began as a bit of fun, but then quickly turned into something a lot more serious, gruelling, and frankly…painful.

I have a confession to make to you…

The first draft of this book was finished over two years ago.

Yes, you read that correctly.

I regret that I’ve left fans of this series hanging for so long since the release of Lykoi (Part II). However, I wasn’t ready to deal with Thanatos for some time after typing ‘The End’ on it.

This is where I get very personal with you, dear readers.

You see, when I was about half way through writing this story, my father passed away very suddenly. He was alone, away from his family, on his way to work.

The event hit my family like a Dacian raiding party in the dead of night.

I was floored…paralyzed.

But I knew that if I did not finish Thanatos then, while I was in the flow, I never would. So, a few days after this sad occasion for my family, I sat down for hours one night and fought my bare-fisted, bloody way to the end of the novel.

People say that when times are tough, writing can be one of the most cathartic activities you can undertake.

And you know what?

It’s true. Despite the brutality of that writing session, and the darkness of the story itself, it did help me in a way.

When it was done, when I finally typed ‘The End’, my grief poured out and the fog I had been caught in began to lift.

For a long time, I wondered how bad the story might be, that I might have just dumped my chaotic grief onto the page. That’s another reason this took so long to get out.

But this past fall, I finally handed the manuscript to my editor, dreading the feedback I would get and the sight of red all over the paper like vicious sword wounds.

It seems however, that pain and brushes with death can indeed give life to creativity.

When she returned the manuscript of Thanatos to me, my editor told me she thought it was perhaps one of the best things I’ve written yet.

Now for a bit about the story itself…

As I mentioned, The Carpathian Interlude series was originally intended to be a bit of fun, but it quickly became serious.

Despite the fantastical elements of the stories with zombies (Immortui) and werewolves (Lykoi), a fair amount of research has gone into these novels, and Thanatos is no exception. As always, I have striven for accuracy when dealing with the historical parts of these books.

Mithras and Mithraism, which was an important religion among Roman soldiers, are a big part of these books. Thanatos really delves into ancient Zoroastrianism, of which Mithraism is a part.

The historic event that these books revolve around is the Battle of the Teutoberg Forest in A.D. 9, in which Quinctilius Varus lost three of the Emperor Augustus’ legions in the forests of Germania. It was a time of terror in the Empire.

I also did a great deal of research into Dacians, their gods, and the Dacian capital of Sarmizegethusa for Thanatos; it was a fascinating rabbit hole to fall into.

For those of you who like the follow the history and research of my novels, never fear, for later this year I’ll be posting a blog series called The World of The Carpathian Interlude. Stay tuned for that.

Some of you may also be wondering about the title of Thanatos.

‘Thanatos’ is the Greek word for ‘Death’. This is deliberate on my part, and directly tied to the Carpathian Lord in the stories.

However, that is where the ties to the ancient Greek image of ‘Thanatos’ ends.

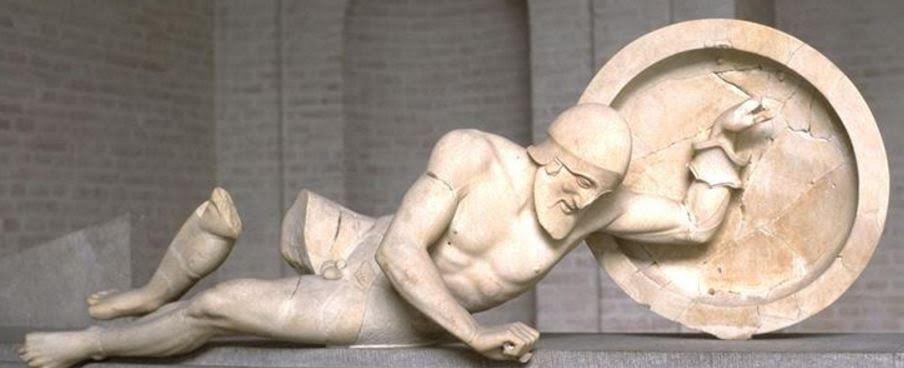

In ancient Greek tradition, Thanatos was a winged god, the twin brother of Hypnos (Sleep). In Hesiod’s Theogeny, Thanatos is the son of Nyx (Night) and Erebos (Darkness).

Thanatos was the personification of Death, and to the ancient Greeks, it was his duty to usher the spirits of the dead to the appointed place, a role later more associated with Hermes. To the ancient Greeks, he was a dreaded god, but not wicked or evil.

In Part III of the Carpathian Interlude, Thanatos is a much more ancient evil, an enemy of the gods in the battle between Light and Dark.

As I said, there will be a blog series about all the research for the Carpathian Interlude trilogy coming out later this year.

In the meantime, I do hope you enjoy this new story, and that it gets you thinking, even in the darkest of places.

Thank you for reading, and may you walk in the Light…

To get a copy of Thanatos, or read the synopsis of this final part in The Carpathian Interlude, just click the link below to go to the book’s page:

http://eaglesanddragonspublishing.com/books/thanatos-carpathian-interlude-part-iii/

Slavery in ancient Rome – A guest post by A. David Singh

Salvete readers and Romanophiles!

This week on Writing the Past, I’d like to welcome fellow author, A. David Singh, who has written a fantastic piece for us about slavery in ancient Rome.

You probably know that slavery was widespread in the Roman world, but what you might not know are the ins and outs of slaves’ lives.

Check out David’s post below for a brilliant introduction to this topic…

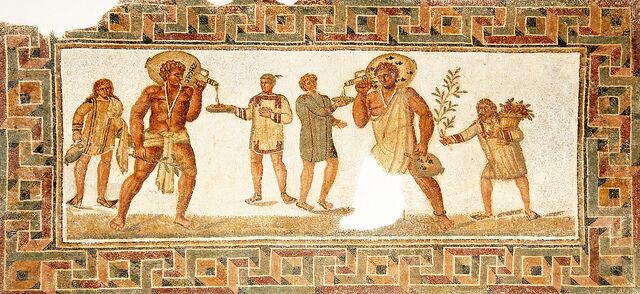

Slaves serving at a banquet – mosaic floor. Found in Dougga, Tunisia, 3rd century A.D. (Dennis Jarvis_Flickr)

In the first century A.D., over a million people lived in Rome — and a third of them were slaves.

Ancient Romans considered their households to be a microcosm of the state of Rome, and slaves were an integral part of their households. Slavery was such a key foundation of their society that if an ancient Roman were to time-travel to the present day, he would be surprised to see a society function just fine without slaves.

In addition to cooking, cleaning, and carrying loads within their master’s household or country estate, slaves served another important function — that of elevating the social status of their masters. This is much the same prestige that a champion race-horse confers upon its owner.

How did one become a slave?

Being born into slavery was the commonest way. Children born to a women slave automatically became slaves to her master.

Another way was by capturing enemies. As Rome waged wars far beyond its borders — in Europe, Asia and northern Africa — a steady supply of prisoners of war poured in, who, in lieu of their lives being spared, were sold to the slave-traders. During his Gallic campaigns, Julius Caesar is rumored to have captured over a million prisoners of war in Gaul and sold them into slavery.

Criminals too could be enslaved, but their masters had to be careful about their violent streak. Unwanted babies who were thrown into rubbish dumps outside the city, though technically free, could be picked up by slave dealers or surrogate parents who would sell them into slavery. A similar fate awaited children kidnapped by pirates and other shady elements of society.

Finally, free Roman citizens, if deep in debt, could be forced into slavery. Some of them voluntarily chose to become slaves to repay their debt. However, Roman citizens submitting to slavery was considered illegal.

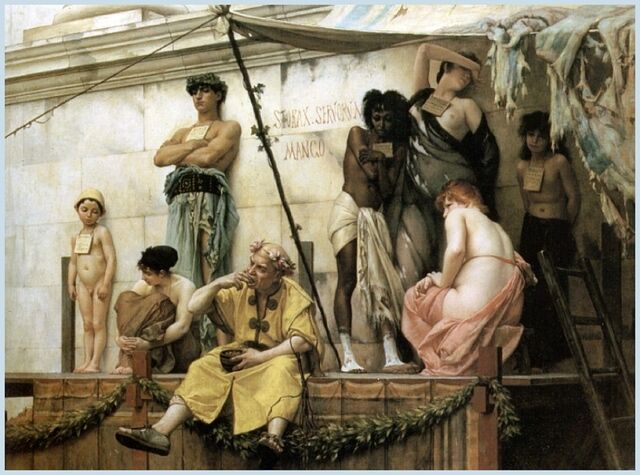

Where were slaves sold in Rome?

The slave market was commonly held behind the temple of Castor and Pollux, and also near the Pantheon. Men, women and children were displayed on raised platforms, just like fruit stands in a bazaar. They wore dejected looks, being resigned to their fates.

The slave trader adorned them with signboards around their necks with information like place of birth and other personal characteristics. It was a common spectacle to see signs like: Gaul, cook, specializes in making spicy fish and the use of Garum or Greek, ideal for teaching philosophy and reciting verses during parties.

Those who came to buy slaves found it in their interest to ensure that the slaves had no physical or mental defects. So, a thorough examination of their bodies was a common occurrence, and putting them on raised platforms helped to do just that.

A young male, 15 to 40 years old, cost 1,000 sesterces, while a female was priced at 800 sesterces. Much younger slaves or those older than 40 years went cheaper. Of course, prices would have been higher for slaves with special skills like reading and accounting.

The slave market had different days allocated for selling different types of slaves. There was a day for selling strong, muscular slaves meant for heavy labor. Another day for those specializing in trades like bakers, dancers and cooks. Boys and girls meant to work in houses and for banquets had their own day of sale, as did those with physical deformities.

What happened afterwards?

Once they started their lives of servitude, not all slaves had the same luck. The best deal that a slave could hope for was becoming a house slave to a kind master — even better, if the master was an important man in Rome. Moreover, there was also the possibility of being freed one day.

Then there was a class of slaves who worked in shops, under the command of an ex-slave. In addition to lugging heavy loads, they had to contend with the emotional baggage of their boss’ recently concluded life as a slave.

Those less fortunate were sold into miserable hovels of brothels, used pitilessly till they broke down or became useless. But a worse fate awaited those slaves who worked in country estates and mines. They lived in pathetic conditions with little food, frequent beatings, and were even locked in filthy prisons at night. It’s no wonder that they had very short life expectancies.

Wealthy Romans were not the only people to own slaves. The state of Rome had its own collection. These slaves were of another class — public slaves. They worked in public baths, food warehouses, or constructed roads and bridges, or worked in public administration offices. They helped in running the economy of Rome. Life was probably kinder to them than to their counterparts who worked in the mines and country estates.

The conditions for slaves were extreme during the Roman Republic. But it is believed that they eased later on. During the Empire, slaves could earn money, get married (informally) and have children. Killing of slaves was banned.

The Slave Market – oil painting by Gustave Boulanger, 1886 (Wikimedia Commons)

What were master-slave relationships like?

In rigid households, slaves were considered nothing more than objects that could talk and walk. They could be sold, rented, or replaced, just the way we do nowadays to our inanimate possessions. The master always decided the level of relationship permitted to their slaves. They could be friendly, or exploit their slaves, or in extreme circumstances even kill them.

On the other hand, if a slave killed his master, then all the other slaves in the household were slaughtered under the charge that they failed to protect their master from the rogue slave.

However, many masters considered slaves as human beings, worthy of moral behavior, and hence treated them with a degree of respect.

Each master had to balance how he treated slaves with the need to keep them working. Brutal treatments were rare because they would wear out the slaves.

Home-born slaves were most likely to remain loyal to their masters, considering him like their own father (which, in many cases he really was). However, barbarians captured from distant lands took some time to be broken into their new, reduced station in life.

Most often, masters incentivized slaves to work hard and stay loyal. Firstly, they rewarded hard work with generous rations of food and clothing. At times, even allowing them to have children, and occasionally organized sacrifices and holidays for them. Such acts of generosity went a long way in ensuring their slaves’ loyalty.

Secondly, slaves had clearly defined job roles, suitable to the their mental and physical attributes, like cooks, door-keepers, or food-servers. This division of labor generated accountability, as the slaves knew that they could be punished only for jobs that they were responsible for, and not for duties outside their job descriptions.

But the most important incentive for slaves to work honestly and with diligence was the possibility of gaining their freedom and becoming Roman citizens.

Manumission

Unlike the Greeks, the Romans took a liberal view of slavery, regularly incorporating slaves into their own society. Thus slavery was viewed as a temporary state, after which, if the slave had shown the right attitude, they could be set free and become a Roman citizen.

This process of leaving the shackles of slavery and becoming free men and women was called ‘manumission’.

If a master was happy with a slave’s services and felt him worthy of being free, the slave could be set free by appearing before a magistrate. Once the magistrate had confirmed that the slave was a free man, the master would often slap the slave, as a final insult, before he started his new life.

Often, a master would bequeath his slaves’ freedom in his will. This is how most slaves got their freedom. In rare cases, slaves could also buy their freedom, if they could raise enough coin — or get another freedman to buy their freedom.

Manumission was generally practiced in urban regions, where it was possible for slaves to form meaningful relationships with their masters and be in their good books. Those working in country estates or mines did not have direct contact with their masters, and were usually worked to death.

Relief showing manumission of a slave. Marble, 1st century B.C. Musèe Royal de Mariemont (Ad Meskens_Wikimedia Commons)

Those slaves who gained freedom became citizens of Rome, enjoying all civil rights. But this freedom came at a cost: they were obligated to their former masters, who now became their patrons, and the slaves became their clients. As clients, the former slaves had to provide ongoing services, stipulated by their patrons before manumission.

In return for their services, the freedmen received patronage from their former masters in the form of helping them set up businesses, giving them financial assistance, and providing them with contacts, or opening doors in the Roman society.

However, freedmen, though Roman citizens, were ineligible to hold political offices. This rule did not apply to any children born to them after manumission. Such children were freeborn citizens and hence could hold political office.

Sadly, any children born before manumission were not so fortunate, because they remained as slaves in their former master’s household — but as was often the case, the parents bought their freedom once they were rich enough.

Even though freedmen moved out of their former masters’ house, they were still considered part of the household. Some patrons even allowed their former slaves — now clients — to share in their family’s tomb.

In essence, manumission was truly the lifeblood of Rome. It provided generations of new citizens hungry to make their way up in society. Since they could not hold political office, the only way to fulfill their ambitions was by acquiring wealth.

Later, it became a cultural norm that rich freedmen married into traditional, but impoverished, Roman families. This proved to be of mutual benefit — the old Roman families became richer, thanks to the nouveau riche, while the freedmen improved their social standing and circle of influence.

In today’s world, the concept of slavery is outrageous because of the prevalent traditions of civilized society. However, in ancient Rome, slavery was a well established institution. In fact, Rome would have collapsed had there not been any slaves because the Romans did not have complex machinery, like we do, to replace human muscle.

The notion of slavery in ancient Rome should, therefore, be viewed within the context of a different era, where society was entrenched in another set of values.

What practices in our current times, do you think, will be considered outrageous, even barbaric, by future generations? Tell us your thoughts in the comments below.

Author Bio

A neurosurgeon by profession, A. David Singh operated on brains invaded by tumors, aneurysms, and other vile maladies. Funnily, after turning a couple (or more) gray hairs, a rather strange affliction invaded his own brain. Characters from a parallel universe besieged his brain cells and refused to leave, unless David transcribed their lives onto paper. At first, he resisted the assault on his cerebral faculties, but these denizens of the Magical Rome Universe kept prodding his gray cells with their antics, forcing him to write their story.

I’d like to thank David for taking the time to write this fascinating post for us. More often than not, writers focus on the great people of the Roman world, but just as the legions were the backbone of Rome’s military might, so were slaves that of Roman society.

Even though the thought of slavery is definitely unsavory, we can’t forget that it was a major part of the Roman world. Thanks to David for reminding us of that.

Everybody, be sure to sign-up to his mailing list and get the Free books he is offering. It’s always good to have more ‘Ancient Rome’!

As ever, thank you for reading…

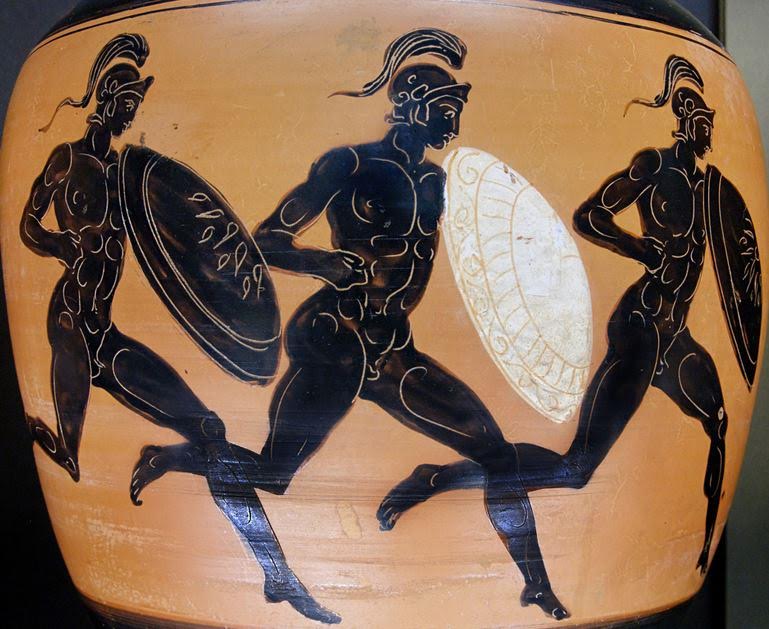

The World of Heart of Fire – Part X – A Novel of the Ancient Olympics

This is the final post in The World of Heart of Fire blog series.

I sincerely hope you have enjoyed it.

Writing Heart of Fire has been a tremendous journey into the world of Ancient Greece. Yes, I am an historian and I already knew much of the material, but I still learned a great deal.

The intense, and in-depth, research, some of which you have read about in this ten-part blog series, made me excited to get stuck in every day. A lot of people, after an intensive struggle to write a paper or book, are fed up with their subject afterward, but that is not the case for me.

In writing this story, and meeting the historical characters of Kyniska, Xenophon, Agesilaus, and Plato, in closely studying their world, I have fallen even more in love with the ancient world. I developed an even deeper appreciation of it than I had before.

In creating the character of Stefanos of Argos, and watching him develop of his own accord as the story progressed (yes, that does happen!), I felt that I was able to understand the nuances of Ancient Greece, and to feel a deeper connection to the past that goes beyond the cerebral or academic.

I’ve come to realized that in some ways we are very different from the ancient Greeks. However, it seems to me that there are more ways in which we have a lot in common.

Sport and the ancient Olympics are the perfect example of this.

We all toil at something, every day of our lives. Few of us achieve glory in our chosen pursuits, but those who do, those who dedicate themselves to a skill, who sacrifice everything else in order to reach such heights of glory, it is they who are set apart.

In writing, and finishing, Heart of Fire, I certainly feel that I have toiled as hard as I could in this endeavour. My ponos has indeed been great.

There is another Ancient Greek idea that applies here, that comes after the great effort that effects victory. It is called Mochthos.

Mochthos is the ancient word for ‘relief from exertion’.

Athens 2004 – Mochthos

My moment of mochthos will come when I return soon to ancient Olympia. I have been there many times before, but this time will be different, for I will see it in a new light – the stadium, the ruins of the palaestra and gymnasium, the Altis, and the temples of Zeus and Hera… all of it.

For me, Olympia has exploded with life.

When I next walk the sacred grounds of the Altis, I’ll be thinking about the Olympians who competed this summer and in the years to come.

They deserve our thoughts, for to reach the heights of prowess that they do to get to the Games, they have indeed sacrificed.

Athens 2004

I always feel a thrill when I see modern Olympians on the podium, see them experience the fruit of their toils, their many sacrifices.

It is possible that they may have been shunned by loved ones or friends for their intense dedication and focus. It can be a supremely lonely experience to pursue your dreams.

Whatever their situation, Olympic competitors deserve our respect, and just as in Ancient Greece, their country of origin should matter little to us.

Yes, we count the medals for our respective countries, but what really matters is that each man and woman at the Games has likely been to hell and back to get there.

Athens 2004 proud winner

When I see the victors on the podium, when I witness the agony and the ecstasy of Olympic competition, I can honestly say that I have tears in my eyes.

Perhaps you do too? Perhaps the ancient Greeks did as well, for in each individual victor, they knew they were witnessing the Gods’ grace.

It’s been so for thousands of years, and it all started with a single footrace.

It is humbling and inspiring to think about.

Heart of Fire – A Novel of the Ancient Olympics is out now, and I hope that I have done justice to the ancient Games and the athletes whose images graced the Altis in ages past.

A Mercenary… A Spartan Princess… And Olympic Glory…

When Stefanos, an Argive mercenary, returns home from the wars raging across the Greek world, his life’s path is changed by his dying father’s last wish – that he win in the Olympic Games.

As Stefanos sets out on a road to redemption to atone for the life of violence he has led, his life is turned upside down by Kyniska, a Spartan princess destined to make Olympic history.

In a world of prejudice and hate, can the two lovers from enemy city-states gain the Gods’ favour and claim Olympic immortality? Or are they destined for humiliation and defeat?

Remember… There can be no victory without sacrifice.

Be sure to keep an eye out for some short videos I will be shooting at ancient Olympia in the places where Heart of Fire takes place. I’m excited to share this wonderful story with you!

Thank you for reading, and whatever your own noble toils, may the Gods smile on you!

If you missed any of the posts on the ancient Olympic Games, CLICK HERE to read the full, ten-part blog series of The World of Heart of Fire!

If Heart of Fire – A Novel of the Ancient Olympics sounds like a story you enjoy, you can download the e-book or get the paperback from Amazon, Kobo, Create Space and Apple iBooks/iTunes. Just CLICK HERE.

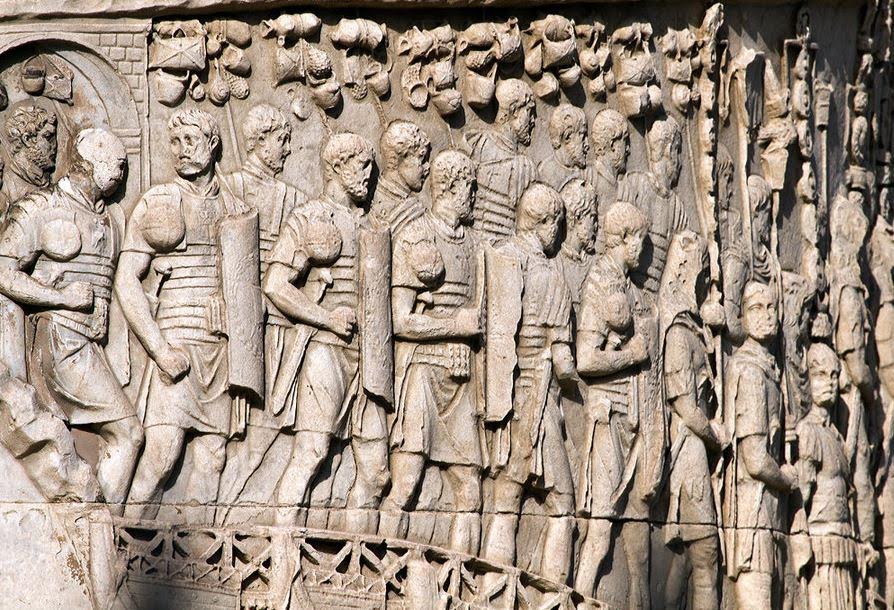

The World of A Dragon among the Eagles – Part II – The Imperial Roman Legion

The world in which A Dragon among the Eagles takes place, and with which the main characters are concerned, is also the world of the Roman legion.

Indeed, the imperial Roman legion figures largely in the entire Eagles and Dragon series, and so, I thought it good to do a brief introduction of the make-up of the legion at the time the book begins in A.D. 197.

Roman legionaries on Trajan’s column

At this time in the history of the Roman Empire, the Roman legion is a well-oiled machine. It, and its troops, had been perfected after centuries of warfare, of trial and error, victory and defeat.

This army, the army of the Principate, is quite different from that of the Republic. It used to be that Roman legionaries were required to meet minimum requirements of possession and wealth in order to qualify for service in the ranks.

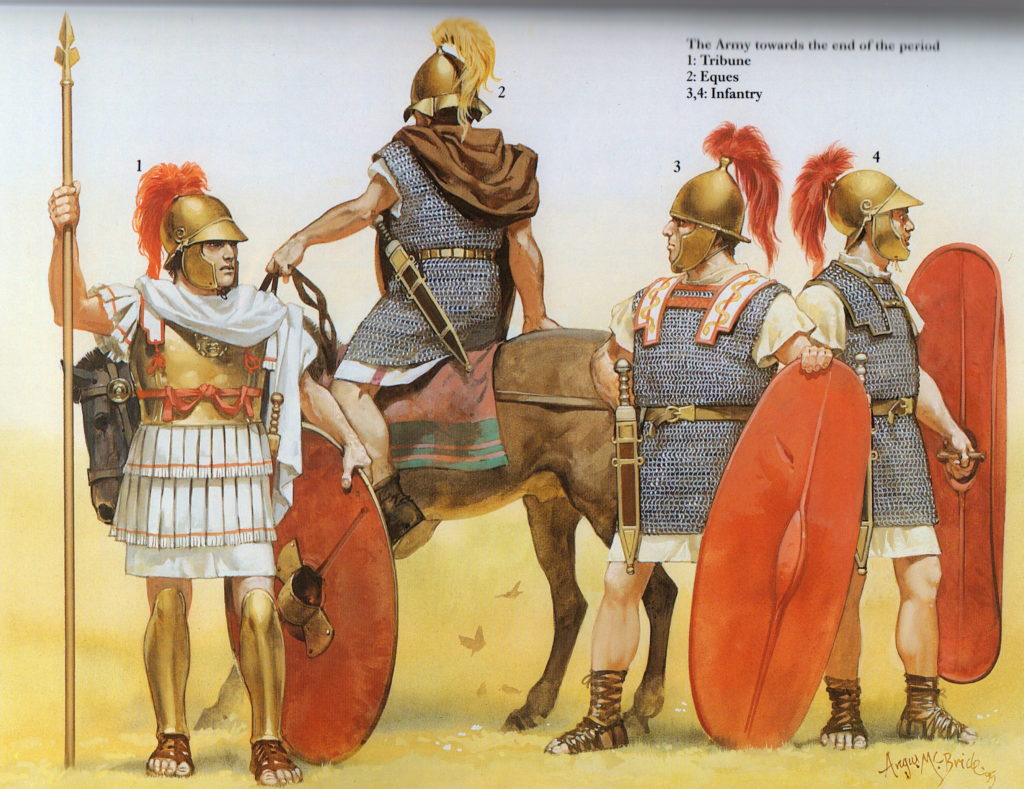

Republican Roman troops (illustration by Angus McBride)

This all changed in 107 B.C when Caius Marius was elected consul and sent to Numidia to continue the war there. However, Marius was denied the right to raise new legions in Africa, permitted only to take volunteers with him.

Of course, Marius took advantage of this, and in a move no other had taken, he appealed to the poorest classes of citizens who became known as the capite censi.

These ‘head count’ citizens were enthusiastic about joining the legions and the new opportunity for a livelihood that it presented them with. They became the backbone of the Roman Legion, and from that time onward the link between military service and property was done away with. They need only have been citizens.

Gaius Marius among the ruins of Carthage (Joseph Verner 18th century)

Marius made many reforms to the Roman army which I won’t go into here, however, his move contributed to the creation of a permanent, full-time citizen army, a self-sufficient fighting force of well-trained men with standard-issue equipment, food and lodging. They carried everything they needed on the march on their own backs, including weapons, spikes for palisades, pots, pans, and pick-axes for digging fortifications.

Marius’ Mules – Re-enactors marching in full kit

Because of all the kit they carried in the field, they became known as ‘Marius’ Mules’.

The average kit for a rank-and-file soldier in the imperial legions included hobnail sandals known as caligae, a standard tunic, a leather belt or cingulum, a lorica segmentata which was a breast plate made up of individual iron strips, a helmet, cloak, gladius (short sword), pugio (dagger), a pilum (javelin), and a scutum (shield).

Re-enactor in Roman Legionary outfit

In A Dragon among the Eagles, there is mention of the various ranks and units that make up the legion, so I think it a good idea to cover the basics now.

The smallest unit of men in the imperial legion was a contubernium which consisted of eight men who shared a tent, or barrack room. These men marched, fought, lived, and cooked together.

Then there was the century. This is probably the most well-known unit of men. It consisted of 10 contubernia, and was run by a centurion with a standard bearer and an optio beneath him.

The centurion was usually a career soldier, and a harsh task-master. He wore different armour that was chain mail, usually with a harness decorated with phalerae, decorative discs that represented awards he had been given. The crest of a centurion’s helmet was horizontal, and he carried a short wooden staff called a vinerod, which gave him the right to strike his citizen soldiers in the interests of discipline.

Re-enactor dressed as a Centurion (Wikimedia Commons)

There are stories about a particular centurion in the imperial legions whose nick-name was ‘give me another’ because he was constantly breaking his vinerod over the backs of his men!

Centuries of eighty men were the most flexible military units in the legion. They numbered enough to go on patrol, or building duty, and could manoeuvre effectively in battle.

Now, the next unit of the legion was the cohort.

The imperial cohort was made up of 480 men, and consisted of six centuries let by an Equestrian tribune. The first cohort of a legion, however, was led by a Patrician tribune.

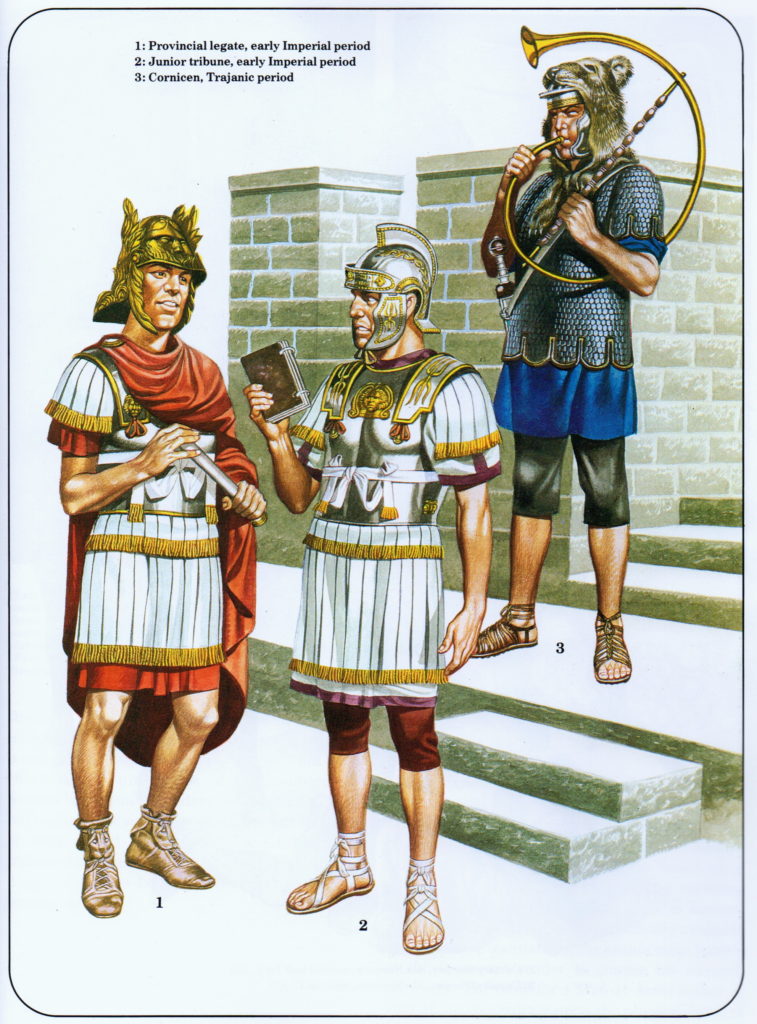

Officers of the Imperial Roman Legions (illustration by Ron Embleton)

Finally, there were ten cohorts in a legion which brought the average number of troops in the imperial legion to 5000.

The commander or general of an entire legion was known as the legatus legionis, or legate commander. This person was usually a senator, just like the patrician tribune who was his second-in-command. The third person of overall authority in the legion was the camp prefect, or praefectus castrorum. The latter was often a career soldier, perhaps a former centurion who had been promoted, and was responsible for much of the legion’s administration and logistics.

There were many other minor positions within the legions such as duplicarii, men who received double pay for skills such as engineering, or the building of siege equipment, as well as benificari, those who were aides to the legate or other officers, and who were excused for intense labour such as the digging of ditches and erecting palisades.

Roman legionary standards with an image of Emperor Severus and his family

We must not forget the standard bearers who made up the imperial legion. These included the vexillarius, the person who carried the vexillum standard of each unit, the signifer, the soldier who carried a century’s standard and wore a wolf or other pelt over his helmet. There was the cornicen, the trooper who carried the cornu, the round horn used to rally the troops and give commands, as well as the imaginifer of the legion, the trooper whose task it was to carry the image of the emperor before the legion.

Probably the most important standard bearer was the aquilifer, the man whose solemn duty it was to carry the legion’s golden eagle, the aquila, into battle. This man was to protect the legion’s eagle at all cost, for it was the ultimate disgrace for a legion to lose its aquila to an enemy.

Re-enactor dressed as an Aquilifer

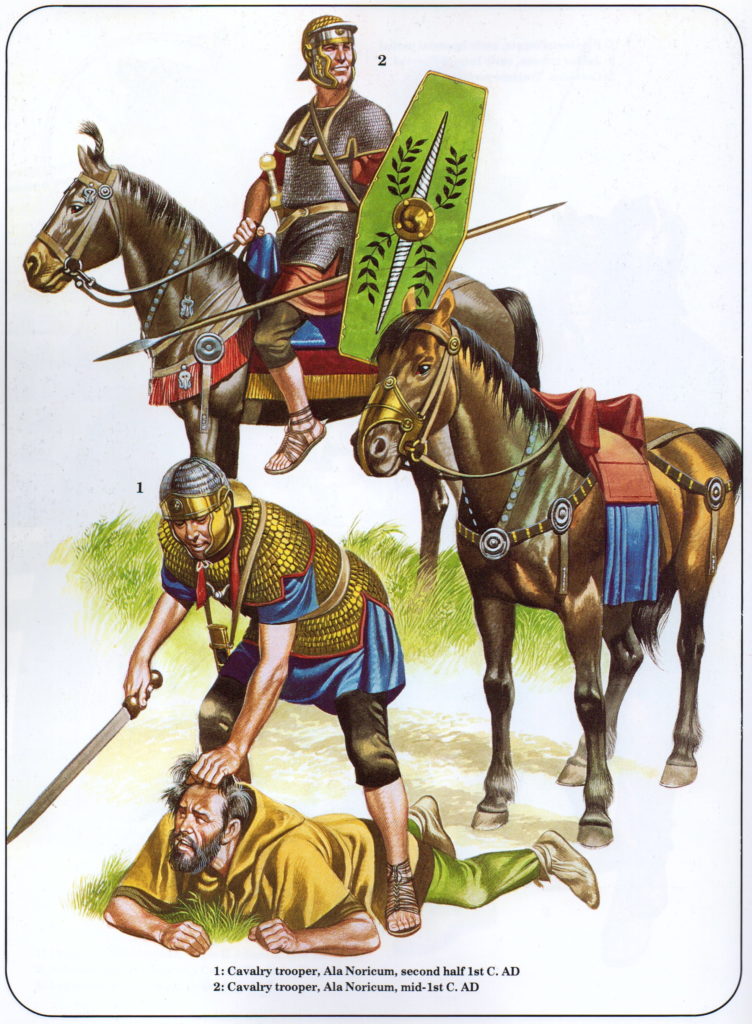

Along with the 5000 regular troops that made up an imperial legion, there were often alae, or auxiliary units, attached to the legion. These were usually units of 120 cavalrymen who acted as scouts and supported the legion on the march. They were often made up of foreign troops who had been brought into the Roman ranks such as Sarmatians, Numidians, or Scythians to name a few.

Ala units might also consist of skirmishers such as Cretan or Balearic slingers, but most often they were cavalry.

Auxiliary Cavalry troops (illustration by Ron Embleton)

The imperial Roman legion was one of the most effective fighting units of the ancient world, and it is no wonder that the Empire covered so much of the known world by the time in which A Dragon among the Eagles takes place.

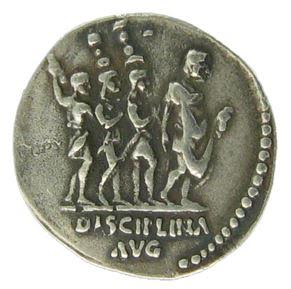

Disciplina, the goddess personification of discipline, was something that was taken very seriously. If a soldier obeyed her and remembered his training, he would survive the direst of circumstances.

Roman coin showing stardard bearers and the world ‘Disciplina’ – second century A.D.

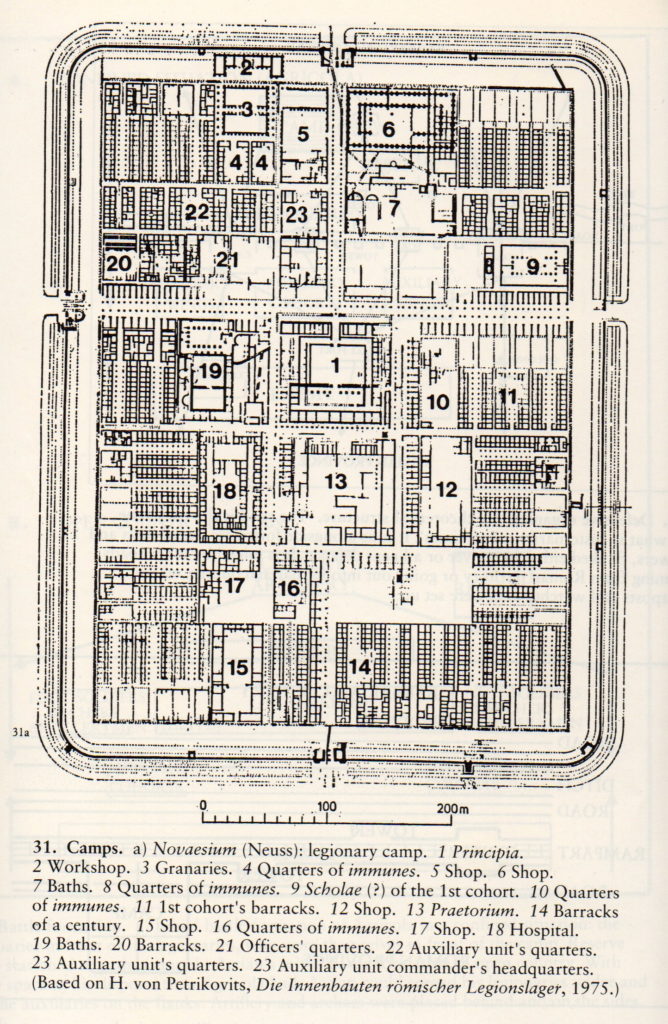

When the legions marched in the field, every night they dug in, every trooper going to his assigned space to dig ditches, pile up ramparts, and raise the palisade around the entire camp.

Tent and command centre, the Principia and Praetorium, tribunes’ tents, stables etc. were always in the same position, the streets set out in the same grid every time. So, whatever happened, a Roman soldier knew where he was, and what he had to do.

Every morning, when they would break camp, they would take down the work of the previous evening, which they had done after a twenty mile march, so that the enemy could not make use of their fortifications.

Plan of a typical legionary fortress (from The Imperial Roman Army by Yann Le Bohec)

It was hard work, but the imperial legion gave opportunity to the poorer classes of Roman citizens and allowed them to make something of themselves, if not at least be clothed and fed at the state’s expense.

In return, the men of the legions bled for Rome as they extended her borders into the world.

A Dragon among the Eagles takes place during the Severan invasion of the Parthian Empire, one of the biggest thorns in Rome’s side for over two hundred years.

In A.D. 197, Septimius Severus set out with one of the largest invasion forces in Rome’s history, made up of a titanic 33 legions.

The stage was set for one of the greatest military campaigns in Rome’s history.

In the next post, we’ll look at this powerful enemy and the tactics they used in battle against the legions.

Until then, check out this great video that illustrates the make-up of the Roman legion.

Thank you for reading!

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=wCBNxJYvNsY

The World of A Dragon among the Eagles – Part I – The Roman Empire in A.D 197

The Legions are marching!

A Dragon among the Eagles – A Novel of the Roman Empire, the prequel book in the Eagles and Dragons series is now out.

To celebrate the release of this action-packed novel, I’m posting a five-part blog series entitled The World of A Dragon among the Eagles.

In this short blog series, I’m going to look at the world in which A Dragon among the Eagles takes place, the Empire itself, the state of the army, Rome’s primary enemies, and the many places of the Middle East where most of the action takes place.

In Part I, we’re setting the scene with a look at the state of the Roman Empire in the year A.D. 197 when this story begins…

The Roman Empire had reached a critical time in its history at the end of the second century A.D., but, despite this, it is a period for which we have very few primary sources.

It is also a period that is often glossed over in fiction and non-fiction today.

That is one of the things that drew me to write the Eagles and Dragons series, that there was/is so little about this supremely fascinating period in the history of the Roman Empire, its people, its geography, and the workings of the great machine that kept it all going, part of which was the army.

A Dragon among the Eagles is the prequel novel to Children of Apollo. It is concerned mainly with the early days of Lucius Metellus Anguis’ enlistment in the imperial legions and his march east in one of the largest invasion forces Rome has ever assembled.

As we know, politics in ancient Rome governed all, and so before we set out on the march, we need to develop a picture of what the Empire looked like in A.D. 197.

Septimius Severus

Septimius Severus is emperor in the year 197, but he actually came to power in A.D. 193. What he established was a huge military dictatorship, but this in fact provided some much-needed stability after the chaos of Commodus’ reign, and the subsequent murder of his successor, Pertinax, by the corrupt Praetorian Guard, after only three months. The Praetorians then auctioned off the imperial throne to the highest bidder, the rich senator Didius Julianus. The latter ruled for just about sixty-six days.

It was at this time, upon the murder of Pertinax in A.D. 193, that Septimius Severus’ troops proclaimed him emperor. He marched on Rome with his legions and promptly discharged the corrupt Praetorian Guard, banishing them from Rome, on pain of death.

Severus then re-appointed his own, fiercely loyal men of the Danubian legions to the Praetorian Guard. He was quick to consolidate power, but things were not yet meant to go smoothly.

Like any good bit of Roman history, civil war ensued.

Two other claimants to the imperial throne came forward with the support of their troops: Clodius Albinus, Governor of Britannia, and Pescenius Niger whose legions were in Syria.

After a few years of bloody fighting on two fronts, Septimius Severus became the sole emperor of the Roman Empire with his victory over Clodius Albinus at the Battle of Lugdunum in Gaul, early in 197.

Marching Legions (Wikimedia Commons)

After many years of turmoil around the imperial throne, the Empire finally had a strong ruler. But this was now an age for the military, and Severus knew how to treat his troops, granting them pay raises, the right to marry, and much more that made him popular.

However, he was not so popular with the Senate because of his use of the military to seize power. Severus was not to be cowed. He held a series of proscriptions to eliminate those senators who had supported his rivals in the civil war, replacing them with men loyal to him.

Severus was now firmly, and safely, on the imperial throne, set to be the most stable emperor since Marcus Aurelius.

This is also an interesting period in history for the role of women, thanks to Severus’ empress, Julia Domna.

Empress Julia Domna was the first of the ‘Syrian Women’ of the Severan dynasty, and the sources, such as Cassius Dio, seem to suggest that she had an almost equal share in power and decision-making alongside her husband. They were the ultimate power couple.

Empress Julia Domna

Julia Domna was said to be highly intelligent, and politically astute. She had a circle of intellectuals from around the world, including philosophers, scientists, and priests who came to talk with her and exchange ideas. It was a sort of ancient Roman salon of great thinkers.

Like all Roman military leaders, Septimius Severus needed a campaign to solidify his claims and busy his troops. Another war against fellow Romans would not do.

So, in A.D. 197, the campaign against Rome’s long-time enemy, Parthia, was set to begin.

We’ll discuss the Parthians in a separate post.

It is important to note however, that in the past many Romans had taken on Parthia and failed. Could Septimius Severus be the one to finally bring the Parthians to their knees?

This is the world in which A Dragon among the Eagles takes place.

A strong emperor is finally in power again. He has numerous loyal legions, and has consolidated his power. He has the love of the Roman people and the troops, if not that of the Senate. And he and his men are itching for a titanic fight.

In the next post on The World of A Dragon among the Eagles, we will be looking at the composition of the imperial Roman legion at this time in history, so stay tuned.

Also, if you have not already done so, be sure to sign-up for the Eagles and Dragons Newsletter so you can be the first to find out about our upcoming releases and special offers.

A Dragon among the Eagles is available from Amazon, Kobo, and very soon from iBooks/iTunes, so be sure to head on over and download your FREE copy today.

Thank you for reading!

A Journey to Hell with Special Guest, Glyn Iliffe

Greetings everyone!

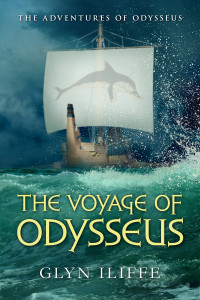

This week, I’m pleased to welcome author Glyn Iliffe back on Writing the Past.

It’s been a couple of years since I interviewed Glyn on the old website around the time of the release of the fourth book in his series, The Adventures of Odysseus.

This time, Glyn is back with a special guest post that I know you will find fascinating!

He has just released book five, The Voyage of Odysseus, which I am reading right now and cannot put down.

Homer’s Odyssey is one of the foundational works of western literature, and the story of Odysseus’ journey back home after the Trojan War is one that has fascinated people for ages.

One of the terrifying elements of this story is the hero’s journey into Hades, and that is what Glyn is going to talk about today.

Katabasis – The Descent into Hell

By Glyn Iliffe

According to Benjamin Franklin only two things in life are certain: death and taxes. The latter we can grumble about and try to dodge, but death is a different question. You might say it’s the question. Being aware of the finite nature of our existence is what separates us from the rest of the animal kingdom and, essentially, makes us human. Death – and what lies beyond it – is the great unknown. The anticipation or fear of it has shaped every culture across the world and throughout time.

To understand the psychology of a culture you need look no further than its art, and a lot of art focuses on death. Enter any Catholic church and you will see depictions of Jesus on the Cross. The tombs of the ancient Egyptians are filled with hieroglyphs illustrating the journey into the afterlife. Indeed, the reason we know so much about our ancestors is because of their obsessions with death, culminating in the desire to take their treasures with them into the next world, or leave monuments to the lives they led before death took them. But the clearest insights into a culture’s views on death come from its stories.

In particular, there is one type of story that appears again and again in the texts of different civilizations from different eras: the descent into Hell. I’m thinking here of a physical journey to the underworld, rather than a symbolic or psychological descent into madness or suffering. Possibly the earliest is Gilgamesh’s visit to Utnapishtim. The Egyptians had the Book of the Dead. The Roman poet Virgil told of Aeneas’s visit to his death father, Anchises; and in the Renaissance Dante’s Divine Comedy describes one of the most memorable and terrifying visions of Hell ever depicted. The most defining katabasis of all, for Western culture, was that of Jesus Christ, who spent three days in Hell after taking mankind’s sins onto himself on the Cross.

The term katabasis comes from the Greek words κατὰ ‘down’ and βαίνω ‘go’, and it is the Greeks we must thank for the most numerous and vivid myths on the subject. In the case of Orpheus, the greatest of all poets and musicians, the journey was undertaken for love. When his wife died after being bitten by a viper, he descended into the Underworld and so charmed Hades and Persephone – King and Queen of the Dead – with his music that they agreed to release her back to him. There was one condition, though: that Orpheus walked ahead of his wife and did not look at her until they had both reached the world of the living. In his anxiety after reaching the upper world, he turned to look at her before she had crossed the threshold of Hades. She disappeared in an instant, and this time it was forever.

A less tragic visitation was made by Heracles, the greatest of all Greek heroes. As a penance for slaying his own family in an episode of madness (induced by the gods, of course), Heracles was forced to serve his weakling cousin, King Eurystheus, for twelve years. Eurystheus set him several labours, the twelfth of which was to capture Cerberus, the three-headed hound of Hell. Hades agreed to let Heracles attempt the feat, but only if he fought without weapons. Despite the fearsome nature of the beast, Heracles succeeded and carried Cerberus back to his cousin. Eurystheus was so frightened he agreed to set no more labours if Heracles would take the hound back!

Teiresias speaks to Odysseus

The most famous katabasis features in Book 11 of Homer’s Odyssey. Odysseus descends into the Underworld to seek the ghost of Teiresias, who will tell him how to find his way home to Ithaca. There he encounters his dead mother and many of the heroes who died during the Trojan War. Chief among them is Achilles, who in life had been the greatest of all the Greek warriors and covered himself in martial glory. But in Hades he is a mournful phantom, scornful of what he had achieved on the battlefield:

‘…We Argives honoured you as though you were a god: and now, down here, you have great power among the dead. Do not grieve at your death, Achilles.’

‘And do no make light of death, illustrious Odysseus’ he replied, ‘I would rather work the soil as a serf on hire to some landless impoverished peasant than be King of all these lifeless dead.’

Odysseus comes away from the Underworld without learning the way back home, which makes the reason for his visit to such a bleak and terrifying place seem pointless. But was it pointless? Indeed, why do some heroes have to descend to Hades? What’s the meaning underlying these myths?

Though later Greeks softened their ideas, in the Bronze Age they believed one thing: that death was followed by an eternity of misery and regret in Hades, relieved only by forgetfulness. Knowing this, many sought the one form of immortality available to them – a reputation that would be honoured from generation to generation. This could only be achieved in battle, by defeating enemies and accumulating honour. This is the driving force for many of the characters in my own novels about the Trojan War.

The katabasis, though, is about symbolic immortality. Importantly, the hero does not reach Hell by the usual route (death). Instead, he seeks to enter the Underworld as a mortal, fulfilling a quest that requires him to take or retrieve something of great worth, such as an object, a person or a piece of knowledge. Interestingly, Odysseus does not return with the knowledge he went in search of, but emerges with something of possibly greater worth: an understanding of the value of life. By achieving his quest the hero proves himself to be exceptional, and by overcoming a figurative death he also becomes more than just mortal. He is reborn into a new life, similar to the Christian baptism ceremony, where the lowering into and rising up again from water is symbolic of death and rebirth.

Wilfred Owen

Such deep themes have inspired many modern retellings of the katabasis. Though the themes are no longer Greek, such stories are still reflective of their own times. Wilfred Owen was an officer in the Manchester Regiment during the Great War. His poetry is full of hell-like visions from the mud and slaughter of trench warfare, but in Strange Meeting there are clear parallels with Odysseus’s descent into Hades:

Yet also there encumbered sleepers groaned,

Too fast in thought or death to be bestirred.

Then, as I probed them, one sprang up, and stared

With piteous recognition in fixed eyes,

Lifting distressful hands, as if to bless.

And by his smile, I knew that sullen hall,

By his dead smile I knew we stood in Hell.

The speaker, like Odysseus with Achilles, tries to comfort the dead man; but like Achilles, the unhappy spirit will have none of it:

‘Strange friend,’ I said, ‘here is no cause to mourn.’

‘None,’ said that other, ‘save the undone years,

The hopelessness.’

The twist comes at the end, where the dead man informs the speaker ‘I am the enemy you killed, my friend’. Though only a glimpse of a descent into Hell, and one from which we don’t know whether the “hero” returns, Owen nevertheless plays on Homer’s suggestion that death is hollow and empty, and that any kind of life is rich by comparison.

A more recent katabasis appears in Phillip Pullman’s The Amber Spyglass, in which Lyra enters the Land of the Dead to rescue her best friend, Roger, who has been murdered. This already has echoes of Orpheus and Eurydice, but there are also other allusions to Greek mythology in the Harpies that patrol this terrible underworld, as well as the phantom-like figures of the dead that populate it. But there are heavy Christian references, too. Like Christ, Lyra leads the lost souls to a form of redemption. Through Lyra’s katabasis Pullman tries to offer an atheistic view of what lies beyond death – very different from traditional descents into Hell – but ironically still relies very heavily on Christian beliefs about redemption.

In The Voyage of Odysseus I retell the story of Odysseus’s long and arduous journey home to Ithaca. The previous books in the series have attempted to draw the full story of the Trojan War into one narrative, focussed on Odysseus. As a fan of Greek mythology, it has always been my intention to be faithful to the original myths and make them accessible, regardless of what the reader may or may not already know about the story. And yet it will always be my take. This is particularly true of the scene in which Odysseus enters the Underworld.

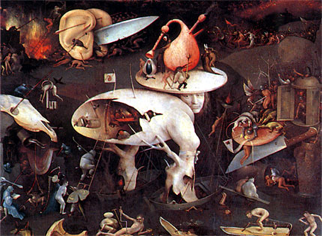

I have had a fear of Hell since childhood. This was probably instigated by seeing Hieronymus Bosch paintings, and reinforced in my teenage years by Dennis Wheatley novels. The notion that Hell is not merely a place of suffering, but a place where the relief of light, love and peace do not exist, is even more frightening. I have incorporated these fears in my retelling of Odysseus’s katabasis – as well as my terror of enclosed spaces!

The Garden of Earthly Delights by Hieronymus Bosch

Glyn Iliffe studied English and Classics at Reading University, where he developed a passion for the stories of ancient Greek mythology. Well travelled, Glyn has visited nearly forty countries, trekked in the Himalayas, spent six weeks hitchhiking across North America and had his collarbone broken by a bull in Pamplona. He is married with two daughters and lives in Leicestershire. He is currently working on the concluding book in the series.

Connect with him on Facebook, or visit his website at www.glyniliffe.com

Be sure to check out The Adventures of Odysseus books at any of the following outlets:

Amazon (UK) – Amazon (US) – Waterstones – Barnes & Noble – Book Depository – Kobo

I’d like to thank Glyn for taking the time to write such an interesting piece for us. I know that whenever I read or write about a character’s descent into Hell or the Underworld, I will be doing so through a new lens.

If you haven’t already read Glyn’s work, I highly recommend The Adventures of Odysseus books. It is definitely one of the best historical fantasy series out there, and despite these being very old stories and characters, Glyn manages to give them new life. Trust me on this one, folks!

For my Eagles and Dragons Newsletter subscribers, Glyn and I have got a special treat which I will be notifying you about shortly by e-mail, so stay tuned for that.

As ever, do be sure to leave your questions or comments for Glyn or myself in the comments section below.

Thank you for reading!

Top 10 Ways to get excited about History

It’s no secret that I love history, and I suspect that if you are reading this blog or my books, you love history too.

This morning I was on my usual commute, herded into the cattle car, surrounded by myriad long faces, when I started to day dream. This time of year, I day dream a lot more, my mind clawing at the distant past, trying to find a way to immerse myself in the comfort of history.

What can I say? I’m a history geek through and through.

The truth is that when this hectic, modern world gets me down, I do indeed find solace in the past. I need to grasp at that thread in the labyrinth to get back to my place of balance.

So, I thought I would share some of the ways in which I connect with and get excited about history. I will do these things not only to immerse myself in history, but also to fire my creativity and imagination so that I am ready to get stuck into the next story.

Here are my Top 10:

#10 – Listen to Period Music

I always write to soundtrack music, but listening to music or interpretations of music from the ancient or medieval worlds is a different sort of experience.

While the music is playing, I may flip through a book, have a glass of wine, or just close my eyes and let my mind wander, imagining myself in an ancient agora, or walking the lonely halls of a castle.

There are a lot of great period music groups out there, one of my favourite medieval ones being the Ensemble Claude Gervaise, their album, Douce Dame Jolie in particular.

There are fewer ancient music groups, but lately I did come across a wonderful album called Musical Instruments of Ancient Greece by the Petros Tabouris Ensemble. I played this during a dinner in which we made some ancient dishes and it really added to the atmosphere. If you have access to Hoopla through your public library system, that is where I found it.

Musical Instruments of Ancient Greece – Petros Tabouris Ensemble

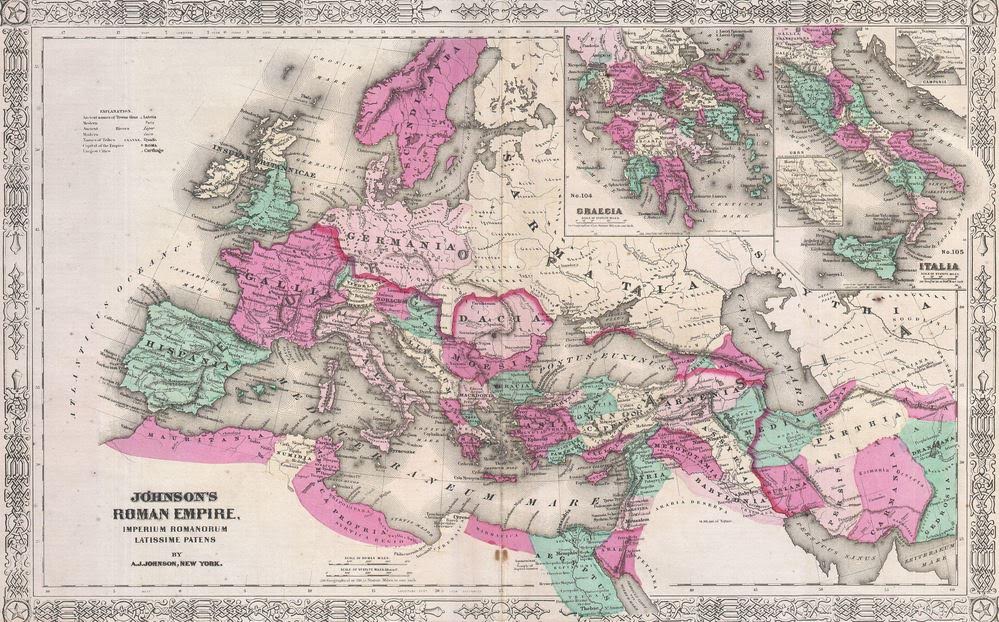

#9 – Maps

I love maps, and I use them frequently in my research and writing as they help me to better visualize the world and period in which I am working.

My favourite maps are the Ordnance Survey maps from Britain. This are military grade maps that give a wonderful level of detail, and the series of historical Ordnance Survey maps are the best for writing historical fiction, or simply exploring the past.

My go-to historical map is the Ordnance Survey map of Roman Britain. I used this a great deal in research in past years, but also when writing the upcoming Warriors of Epona (Eagles and Dragons Book III).

Some of my favourite Ordnance Survey Maps

#8 – Primary Sources

When getting stuck into the past, you can only get so far on secondary sources, sources written by modern or later scholars about past ages.

If you really want to get a feel for a certain period in history, to hear things from the ‘horse’s mouth’ so to speak, then primary sources are key.

Most people are not able to read ancient Greek or Latin, so it’s lucky that almost everything is available in translation. Two series I like are the Loeb Classical Library, which is now available on-line, and the much more affordable Penguin classics range which you can find in most bookstores.

Both of these are fine and can really immerse you in the ancient and medieval worlds.

The problem with some classical or medieval texts is that they can go on sometimes, depending on the author.

I remember reading Froissart’s Chronicles on the Hundred Years War a while ago and being bored by the never-ending lists of nobles. So, for a modern reader, some of these sources can be a bit tedious. But not all of them are boring and, in fact, a great many are quite entertaining.

If you don’t want to pay for some of these primary sources, you can find a lot of them on the Project Gutenberg website, and the Perseus Digital Library.

Loeb Classical Library On-line

#7 – Documentaries

I’ve written before about how I love to watch documentaries in a previous post called ‘Roaming the Past’.

There are so many great documentaries available on YouTube that with the touch of a couple buttons, you can be off on a grand adventure with some of the leading historians of the day.

The thing I like about documentaries is that they are the next best thing to actually going to a site. The presenters often go to places that are not accessible to the average person.

If they are well-done, documentaries are a wonderful way to unwind, to learn, and to escape into the past from the comfort of your own home.

I always get pumped about history after watching a good documentary!

Click here to watch one of my favourites from Michael Wood.

#6 – Big Non-Fiction Books

When it comes historical landscapes, ancient ruins, or castles, a picture definitely speaks a thousand words.

That’s why I love to sit down on a quiet Sunday morning, or after a stressful day at work, and peruse the large, full-colour pages of some of my favourite coffee table books.

I have several of these mighty tomes at home and they can always be relied upon to help me escape into history.

From a book on the Parthenon and ancient Athens, to ancient Rome, the castles of Britain, world archaeology, Egypt, and the travels of Alexander the Great, every time I heft one of these titans I’m guaranteed to get lost for a while in the best possible sense.

Some of my BIG BOOKS!

#5 – Visiting Museums

What better place to get in touch with different periods of history than in your local house of the Muses.

If you live in a big city, chances are you have access to a museum with a decent collection. Two of my favourites are the new Acropolis Museum in Athens, and the British Museum, entry to the latter being free!

You may also have a small, local history museum near you that could be of interest, so be sure to check it out.

Museums are a great way of connecting with people of the past, of getting close to the normal everyday objects that our ancestors used. These can add the texture to the greater historical picture we are imagining.

Having fun at the Trimontium Roman Legionary Museum. So much fun!

#4 – Living History Displays

When it comes to people dressed up in historical costume and swinging swords around, most of you may think of mad Renaissance festival goers with bad accents, and supremely laughable movies like The Knights of Badassdom or All’s Faire in Love (both are on Netflix).

These sorts of flicks can be fun, but they are not the living history displays I’m referring to.

If you want to really get into history, you should go and attend a display of one of the many living history, or re-enactor groups near you.

The people who take part in living history displays are not only die-hard history fans, but also serious researchers who have helped to further our knowledge of the past alongside our academic brethren.

Living history re-enactors use ancient and medieval methods and tools to create weapons and utensils, fabrics, horse-harness and all the other everyday implements of the past. They bring famous battles to life, and put on displays that show us how, for instance, Roman siege engines work.

A display by the Ermine Street Guard re-enactment group

For many people who have been bored by history through textbooks in school, living history re-enactments can be a welcome breath of fresh air that awakens a love of the past.

No matter what historical period you’re interested in, there is certainly a group of re-enactors that fits the bill. Ask around and see what is going on in your area, especially during the summer months.

Many of these groups put on displays at historic sites like Hadrian’s Wall. You can ask some questions, swing a sword, and maybe even try on some armour!

#3 – Watch Movies

Whenever any historical movie comes out, there is never any shortage of complaints on-line about the accuracy, or lack thereof, of the film.

And it is true that most historical movies do not depict the history exactly as it was. Of course not! They are telling a story and they have to work within the confines of their medium, and of their particular budget.

But I love watching movies that take place in an historical setting, even if it is rife with errors. It gets me excited about history. Period.

I loved this movie!

I’ve said before that Robin Hood, Prince of Thieves was the movie that really turned me on to studying history. People laugh at me for that (and that’s ok!), but I say that that movie started me reading everything I could get my hands on about the 12th century, warfare, and the Middle Ages. And in reading further, I found out how things really were. The movie made me want to learn more about history.

Is that a bad thing? Absolutely not!

So, if watching movies is something that you love and enjoy, ignore the critics and just go for it, whether you’re watching 300, Kingdom of Heaven, Troy, Pompeii, Gladiator, or any other period flick. It doesn’t matter, so long as the setting is historical, you are bound to get switched on.

Great scene from Ridley Scott’s epic, Gladiator

#2 – Read Historical Fiction

Now I may be biased here, but I read a lot of historical fiction, almost exclusively.

Setting my bias aside, however, I truly believe that historical fiction, if done well, can both entertain and educate. It can move people’s hearts and minds, and give them an in-depth look at the past, the people, places, ways of thinking, and ways of living.

I really do believe that historical fiction should be on the curriculum for history classes at every level. It brings history to life in a more accessible way than non-fiction text-books, and in a deeper way than any film.

The reader is put smack dab into the history of the period the book is about. The reader can get lost, immersed in the history for as long as they want to read, or until the book ends.

Historical fiction, in a way, paints a more complete picture of the past, and is not constrained by any budget, or medium.

In writing historical fiction, or historical fantasy, anything goes, and there are no limits to the places a reader can be taken.

My current read!

Stay tuned for a big surprise related to this book!

Finally, my number one activity for getting excited about history…

#1 – Site Visits and Travel

I think I fell in love absolutely with history the first time I set foot inside a real castle. I believe it was Warwick Castle in England.

I can remember walking around, not only impressed by the sheer scale of the place, but mesmerized by the battlements, the towers, the rooms filled with armour.

Warwick Castle

Most of all I was amazed by the lives people actually led in the past.

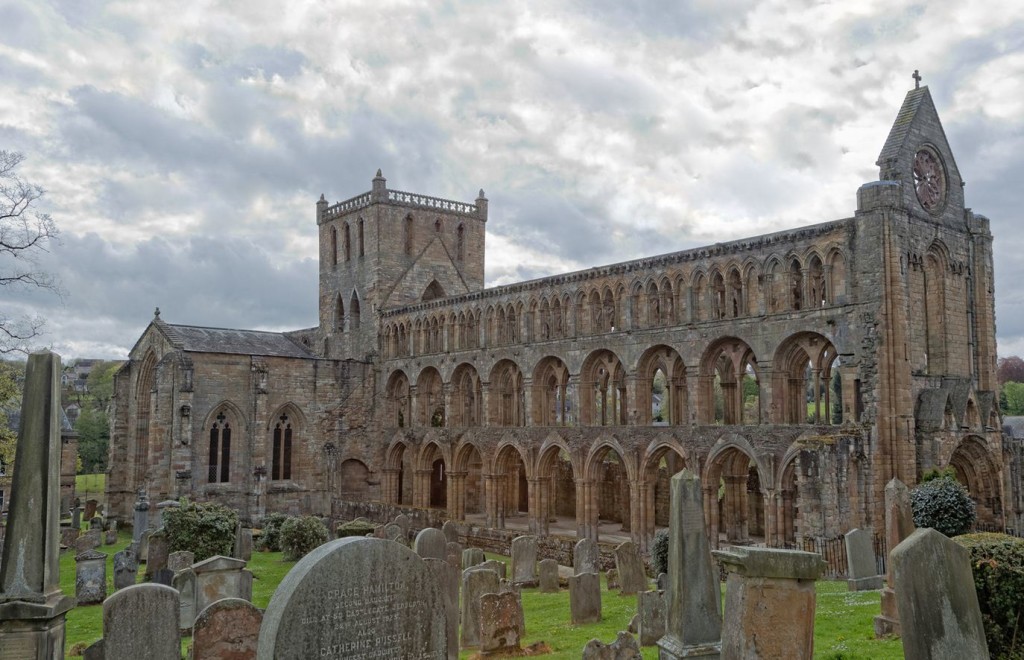

Visiting an archaeological site, a castle, a ruin, or an ancient landscape, however big or small, is unlike any other experience.

I’m a firm believer that travel is the best education, and site visits are the perfect way to put you in touch with history and the people of the past.

I’ve written about the sites I’ve visited a lot on this blog, most recently ancient Argos, Epidaurus, and Nemea, but I remember every time I have visited an historic site. The experiences are burned in my memory.

Every time, I felt like I connected with the people who inhabited that place and age, that I gained a fuller understanding of them. I touched the altars where they worshiped their gods, smelled the air they smelled, heard the way the wind caressed the wall about their dwellings or as it rushed through their forests.

To stand on the top of Hadrian’s Wall I had an inkling of what it was like for a Roman soldier on the edge of the Empire. I’ve walked beneath the Lion Gate of Mycenae on my way to an audience with King Agamemnon, heard the battle cries of 300 Spartans at Thermopylae, and gazed across African olive groves to the Sahara from the arches of a remote desert amphitheatre.

Desert light at the theatre of Thysdrus (El Jem)

Until virtual or augmented reality are perfected, there is no better way to connect with the past than standing where ancient people stood, seeing what they say, touching what they touched.

The problem with this is the cost of travel. I don’t travel nearly as much as I would like. But, if you can manage to save to go to a place of history that you’ve always wanted to visit, the memories of that journey will sustain you for a long time and give you a much greater understanding of the past.

Ipogeo Etrusco de Montecalvario (6th century B.C.)