What is the Isle of the Blessed?

There are many traditions when it comes to paradise, or a place where there is no suffering or pain. To the ancient Greeks, the Fortunate Isles, or Isles of the Blessed were a place where heroes went, a green paradise where the sun always shone. To the Romans, that was Elysium, or the Elysian Fields, the place where heroes blessed by the Gods went to spend eternity in peace.

In the latest Eagles and Dragons series novel, Isle of the Blessed, we find ourselves in a world beyond the water and mist of the Somerset levels of southern Britannia.

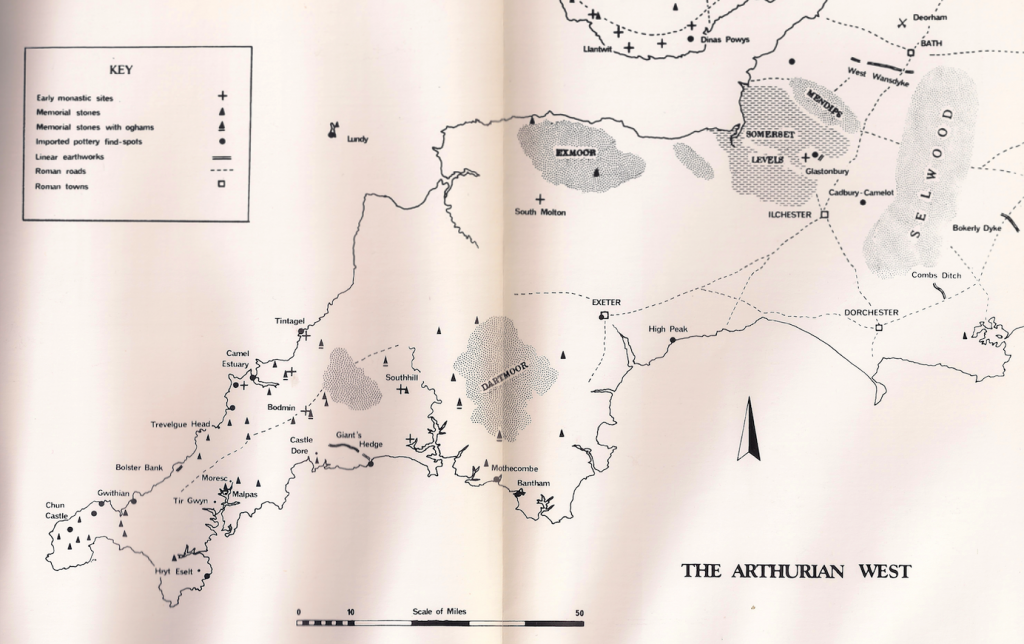

In Part III of The World of Isle of the Blessed, we’re looking at the history, myth and legend of the place known in Celtic myth as Ynis Wytrin, but which we know today as Glastonbury, or the legendary Isle of Avalon.

Glastonbury has always been a special place for me, not because I lived in the countryside outside the town for a few years, or because of its strong Arthurian associations, an area of study and story that I have always gravitated to.

One of the things I love about Glastonbury is the, more often than not, peaceful coming together of various beliefs through the ages.

To most, the mere mention of this town’s name will likely conjure images of wild, scantily clad or naked youths and aged hippies. You’ll think of thousands of people covered in mud as they wend their way, higher than the Hindu Kush, among the tent rows to see their favourite artists rock the Pyramid Stage at Britains’ largest music festival.

It’s a great party, but that’s not the real Glastonbury.

Removed from the fantastic orgy of the music festival, this small, ancient town in southwest Britain is a place of mystery, lore and legend. It is a place that was sacred to the Celts, pagan and Christian alike, Saxons, and Normans. For many it is the heart of Arthurian tradition, and for some it is the resting place of the Holy Grail.

Today, Glastonbury is a place where those seeking spiritual enlightenment are drawn. The New Age movement is going strong here, yet another layer of belief to cloak the place.

When I lived there, I never tired of walking around Glastonbury and exploring the many sites that make it truly unique. I’d like to share some of those sites with you, sites that are featured in Isle of the Blessed, the latest Eagles and Dragons novel.

My morning view of the Tor across the Somerset levels

From where I lived on the other side of the peat moors, I awoke every morning to see Glastonbury’s most prominent feature shrouded in mist – the Tor.

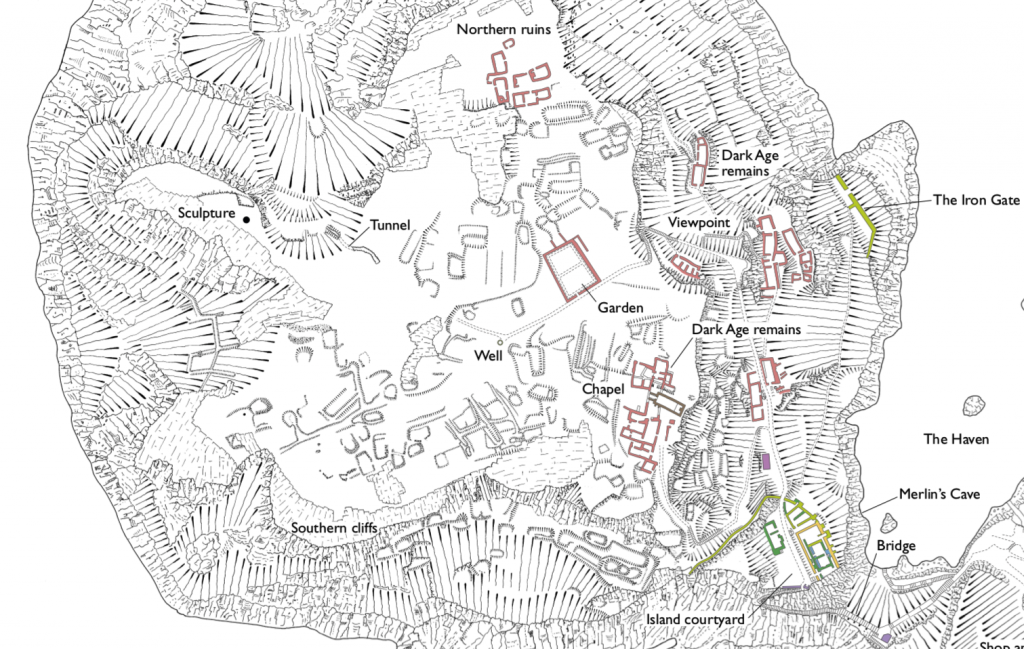

Tor is a word of Celtic origin referring to ‘belly’ in Welsh or a ‘bulging hill’ in Gaelic. Glastonbury Tor thrusts up from the Somerset levels like a beacon for miles around. Every angle is interesting. On the top is the tower of what was the church of St. Michael, a remnant of the 14th century. Before that, there was a monastery that dated to about the 9th century A.D.

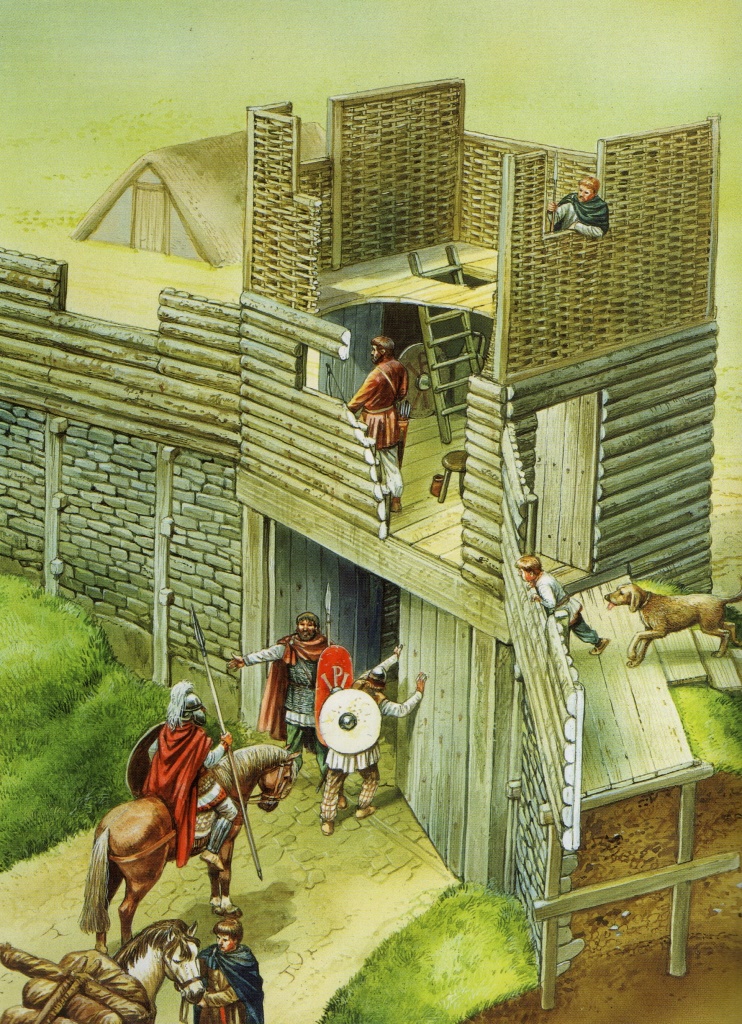

However, habitation of this place goes much farther back in time with some evidence for people in the area around 3000 B.C. It was not always a religious centre. In the Dark Ages, the Tor served a more militaristic purpose and there are remains from this period too.

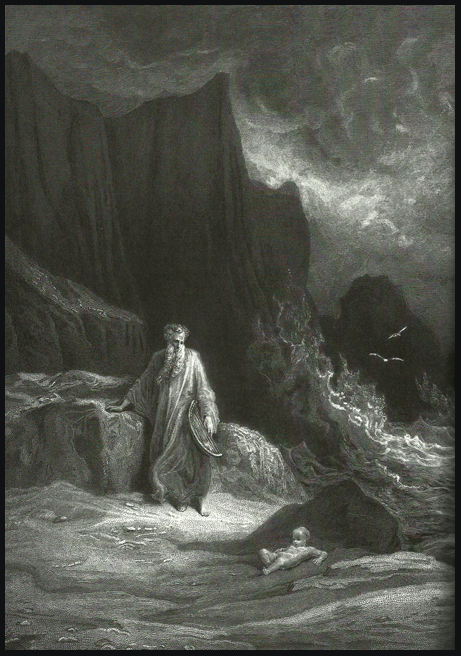

In Arthurian lore, the Isle of Avalon is a sort of mist-shrouded world that is surrounded by water and can only be reached by boat or secret path. In fact, during the Dark Ages and into later centuries, until the drainage dykes were built, the Somerset levels were prone to flooding. This flooding made Glastonbury Tor and the smaller hills around it true islands. With the early morning mist that covers the levels, this watery land would have been a relatively safe refuge for the Druids, and early Christians, Dark Age warlords and medieval monks.

Somerset Levels in flood

In Celtic myth, Glastonbury Tor, one of the traditional gates of Annwn, the Celtic otherworld, is said to be the home of Gwyn ap Nudd, the Faery King and Lord of Annwn.

Gwyn ap Nudd is the Guardian of the Gates of Annwn, an underworld god. It is at Samhain that the gates of Annwn open. This was also the place where the soul of a Celt awaited rebirth.

If you are on the Tor at Samhain, you may hear the sound of hounds and hunting horns as the lord of Annwn emerges for the Wild Hunt of legend.

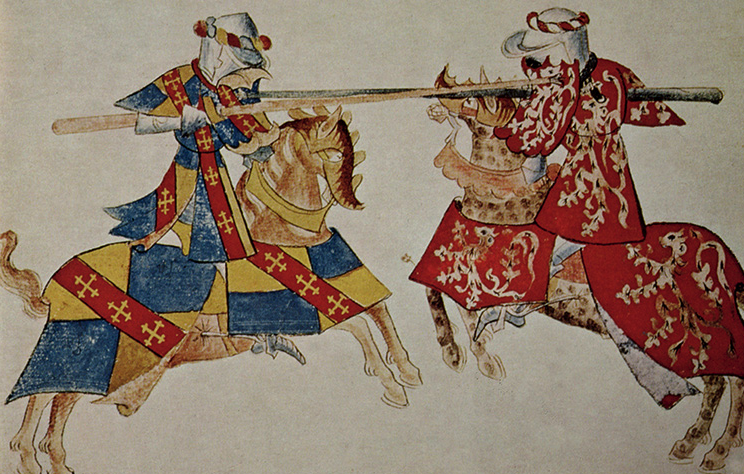

In Arthurian romance, there is a tradition of the wicked Melwas imprisoning Guinevere on the Tor. Arthur rides to the rescue, attacks Melwas and saves Guinevere. This particular story mirrors an episode in Culhwch and Olwen, one part of the Welsh Mabinogion, in which Gwythyr ap Greidawl attempts to save Creiddylad, daughter of Lludd, whom he is supposed to marry, from Gwyn ap Nudd himself.

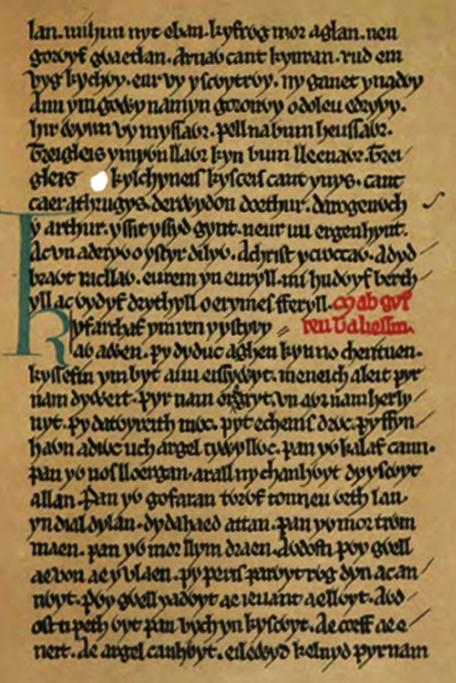

The Book of Taliesin (Wikimedia Commons)

Another even more fascinating Arthurian connection can be found in a pre-Christian version of the ‘Quest of the Holy Grail’, called the ‘Spoils of Annwn’ which was found in the ‘Book of Taliesin’. In this tale, Arthur and his companions enter Annwn to bring back a magical cauldron of plenty. In this, some say that ‘Corbenic Castle’ (the ‘Grail Castle’) is actually Glastonbury Tor. It isn’t just Herakles and Odysseus who journeyed to the Underworld!

Glastonbury Tor is not only associated with Celtic religion, myth and legend. It is also said by some to be a place of power or a sort of vortex in the land that lies along some of the key ley lines, including what is called the St. Michael ley line. The majority of sites associated with St. Michael, the slayer of Satan, along the ley line were indeed places of power and belief of the old pagan religions.

Filming on Glastonbury Tor

Myth and legend persist through story and place, and the Tor is a prime example of how successive traditions do not overcome each other, but rather combine to make up the various aspects of that place.

If you ever get to Glastonbury, the Tor is a definite must. Walk to the top and sit awhile. Look out over the landscape and watch the crows and magpies dive in the wind around the steep slopes. Close your eyes and listen. While you’re there, you can decide whether you are sitting on a natural formation, a ceremonial labyrinth, a hillfort, a sleeping dragon, the Gates of Annwn, or the mound where Arthur sleeps until he is needed once more. The Tor is all of these things.

Wearyall Hill and the Holy Thorn several years ago

Another prominent feature of Glastonbury’s landscape is known as Wearyall Hill, located on the road as you enter from the neighbouring town of Street.

Wearyall Hill is home to one of Glastonbury’s most ancient treasures – the Holy Thorn.

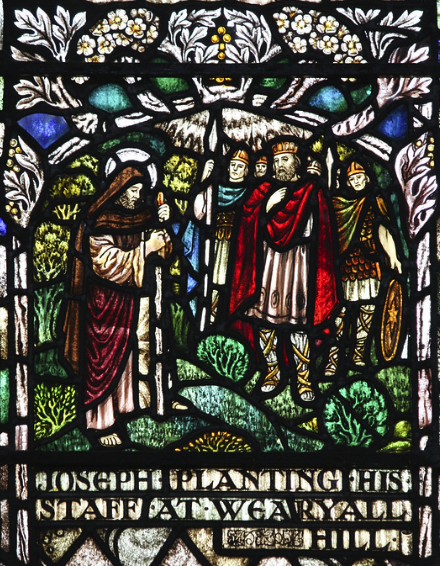

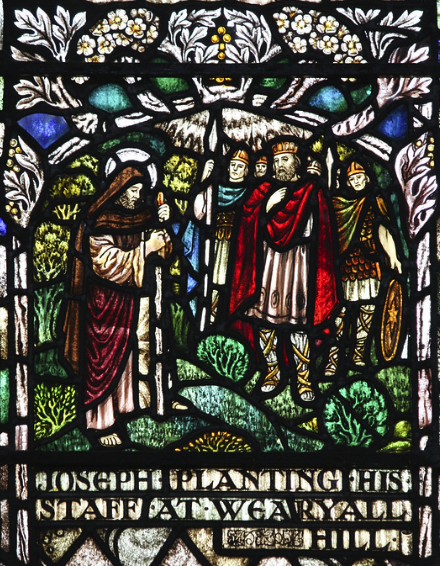

Across the street from the Morrison’s store, you can climb up Wearyall’s gentle slope to see a hawthorn tree known as the Glastonbury Thorn, or the ‘Holy Thorn’. One popular legend associated with Wearyall Hill and the Holy Thorn is that in the years after Christ’s death, his uncle Joseph of Arimathea came with twelve followers by boat to Glastonbury. When they set foot on the hill, tired from their journey, Joseph plunged his staff into the ground and it took root.

There is archaeological evidence for a dock or wharf on the slopes of Wearyall Hill that dates from the period. Did Joseph of Arimathea actually arrive in Britain with the Holy Grail?

Stained glass detail from St John’s church in Glastonbury showing Joseph planting his staff in Wearyall Hill.

Well, that depends on what you believe. And Glastonbury is just that, an amalgam of beliefs living, for the most part, in harmony, just as the Celts and early Christians did here over two thousand years ago.

Cuttings of the Thorn grow in three places in Glastonbury. What is interesting is that this variety of hawthorn is not native to Britain, but is rather a Syrian variety. Curiously, it flowers at Christmas and Easter, both sacred times of year for Pagans and Christians. Every holiday season, the Royal family is sent a clipping of this very special tree that hails from the earliest days of Christianity in Britain.

The current Thorn is not the original, but rather a descendant of the original which was burned down by Cromwell’s Puritans in the seventeenth century as a ‘relic of superstition’. How much destruction has been wrought on the ancient sites of Britain during the wars waged by Henry VIII and later Oliver Cromwell? It’s horrifying to think about.

One of my first visits to Wearyall Hill and the Thorn

As with all other things in Glastonbury, Wearyall Hill and the Holy Thorn do not belong solely to the Christian past.

The hawthorn tree was one of the most sacred trees to the Celts and is the sixth tree on the Druid tree calendar and alphabet. It is also known as the ‘May Tree’ because of when it blossoms most. May was sacred to the ancient Celts as the time of the festival of Beltane, a time for Spring ritual and worship of the Goddess.

In the Middle Ages, the practice of picking hawthorn boughs evolved to include dancing with them around a May Pole.

In Arthurian tradition, Wearyall Hill is associated with the castle of the ‘King Fisherman’ whom the Grail knights meet. To reach the castle, those on the quest were said to have to cross the ‘perilous bridge’ over the river of Death. To pass through the castle was to go from this world to the next.

Interesting to think that the gates to the otherworld of Annwn were believed to be just on the next hill, Glastonbury Tor.

Whatever legend or myth you believe, or don’t believe, about Wearyall Hill is up to you. The stories are many and convoluted, but such is the fate of great and sacred places of the past.

A descendent of the Holy Thorn in Bloom on the grounds of Glastonbury Abbey

I always looked forward to my walks up the gentle slope of Wearyall Hill with the Holy Thorn drawing me up like a beacon, a friend even. Locals, Christian and Pagan believers, hold it close to their hearts.

Once at the top of the hill, I would circle the Thorn, reach out to touch its limbs, and read some of the wishes or prayers on ribbons tied to it – ‘Don’t let me lose my family,’ or ‘Thank you for making my mummy better.’ The wishes wrenched your heart, and the thanks made you smile.

When I would sit on the nearby bench at the top of the hill, I never felt alone. I would look out at the Tor and the surrounding landscape and feel tremendous gratitude. I would always leave with a sense of hope for the future, and a tie to the past.

On my recent visit, long after the vandals struck, there are more wishes than ever upon the Holy Thorn.

When I returned to Glastonbury recently to film a documentary and do some research for Isle of the Blessed, I found the tree much changed from before.

In 2010, vandals took a chainsaw to the Holy Thorn in the middle of the night. In the morning, residents found their beloved tree of hope hacked to bits. A sapling was planted again in the Spring of 2013, but again, that was knocked down in the night.

I’m still in shock over this, lost in my remembrances of Glastonbury’s Thorn in full bloom on a sunlit hilltop.

But the Thorn has survived the centuries and there has been talk that new shoots have been coming up. The Royal Botanical Gardens is on the case, and so are the citizens of Glastonbury.

The Thorn and Wearyall Hill itself are not purely Christian or Pagan. They are symbols of unity, and of a common past. We should indeed cherish sites that are so revered, whether we believe in them or not.

In a way, the Thorn’s sacrifice is bringing people together. Glastonbury is still a town where Pagan and Christian live side by side.

And it is this unity that I explore in Isle of the Blessed.

I have every hope that the Thorn will blossom once again on the crest of Wearyall Hill, and that one day I’ll make the climb to say hello to a very old friend.

This next site we are going to look at is one that, like the rest of Glastonbury, is suffused with layers of history, legend, and belief.

The Chalice Well and surrounding gardens, located in a valley between Chalice Hill and the Tor, is one of those places that you don’t quite know what to make of at first. When you enter under the vine-covered pergola you are met by colour, soft light, and the gentle trickle of water playing about your senses.

You see young, wildly coloured blossoms exploding from the soil at the foot of Yew trees that have seen centuries of summers in Ynis Wytrin.

The same goes for the people visiting this place.

You will see young children frolicking like fairies at the edge of the water, adults of all ages contemplating beauty…life…death.

And you will find aged men and women, whose years are beyond the care of counting, strolling silently about the gardens. They’ll admire a particularly beautiful blossom or sit on one of the many benches hidden in private corners, perhaps remembering others they have come here with long ago. Or maybe they are just looking up at the Tor and harkening back to the tales of Arthur they loved when they too were children.

Peace in the Chalice Well Gardens

The thing about this place is its overwhelming sense of peace and harmony, from which all can benefit.

But what exactly is the Chalice Well?

Scientifically-speaking, Chalice Well is actually an iron-rich spring, the source of which is unknown. Some believe it comes from deep in the Mendip Hills to the north. The Chalice Well is where it comes out of the ground.

Springs were sacred to the ancient Celts. To those who inhabited this area from the pre-historic era on, the Well may have been a healing place beside the Tor. The waters that run red were sacred to the Goddess and were her water of life.

The spring has never failed, even in drought.

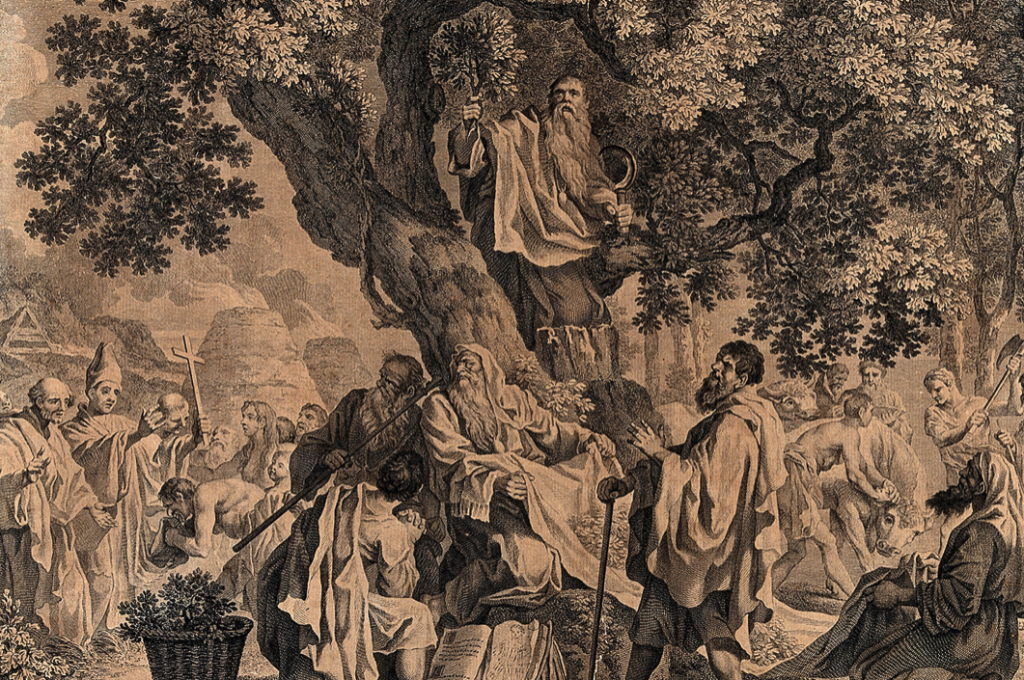

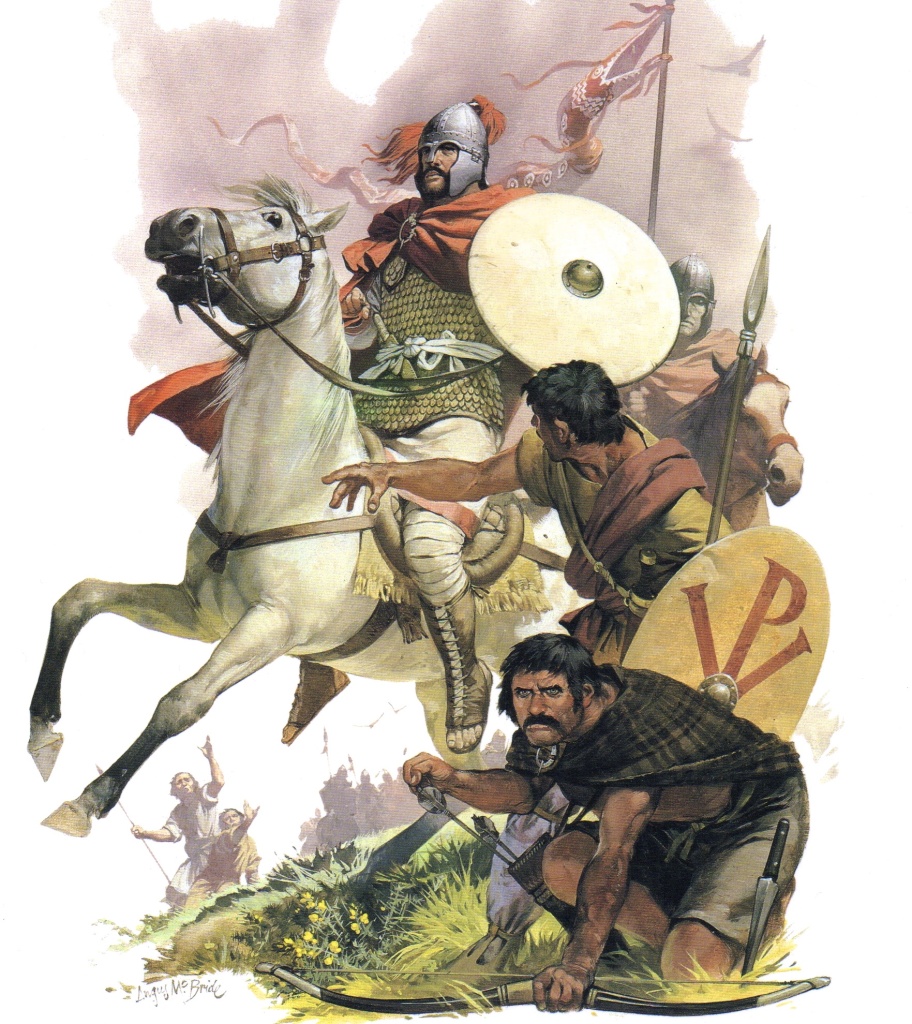

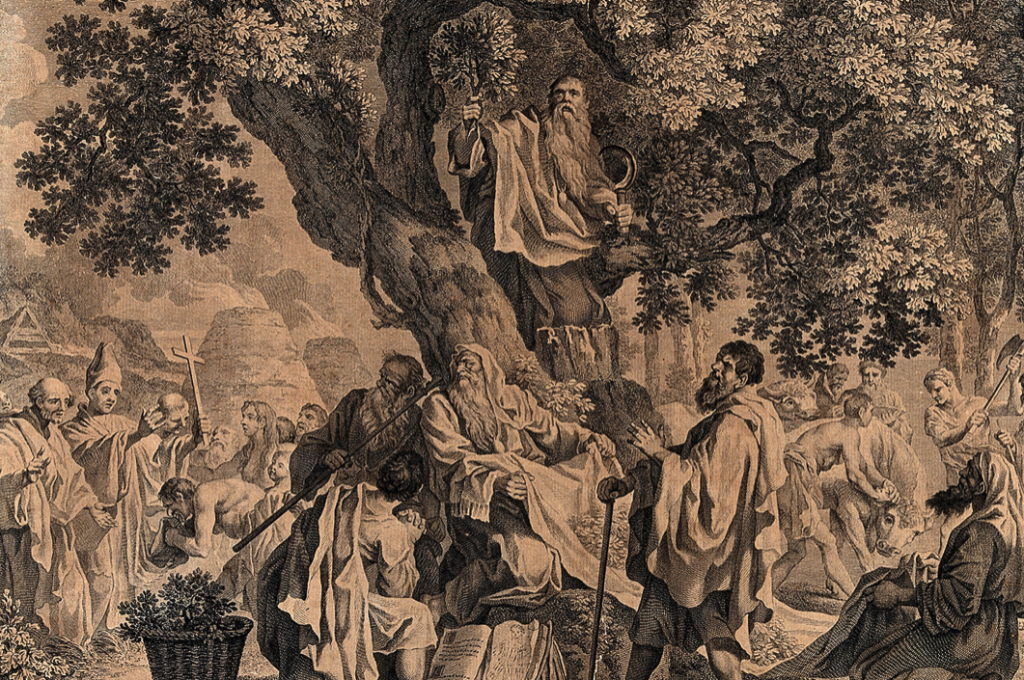

‘The Druids; or the conversion of the Britons to Christianity’. Engraving by S.F. Ravenet, 1752, after F. Hayman.

It is also believed that Glastonbury was the site of a Druid ‘college’ of instruction and that the avenue of sacred Yew trees, some still remaining in the Chalice Well gardens, were part of a processional way to the Tor, passing beside the Well.

Later legend, and the reason for the name given to the Well, relates how Joseph of Arimathea brought the Holy Grail to Glastonbury in A.D. 37. It is said that he buried the Grail near the Well and that the water runs through it, hence the redness of the water.

The Goddess’s blood was replaced by that of Christ, but the sanctity of the place remained (and remains) intact.

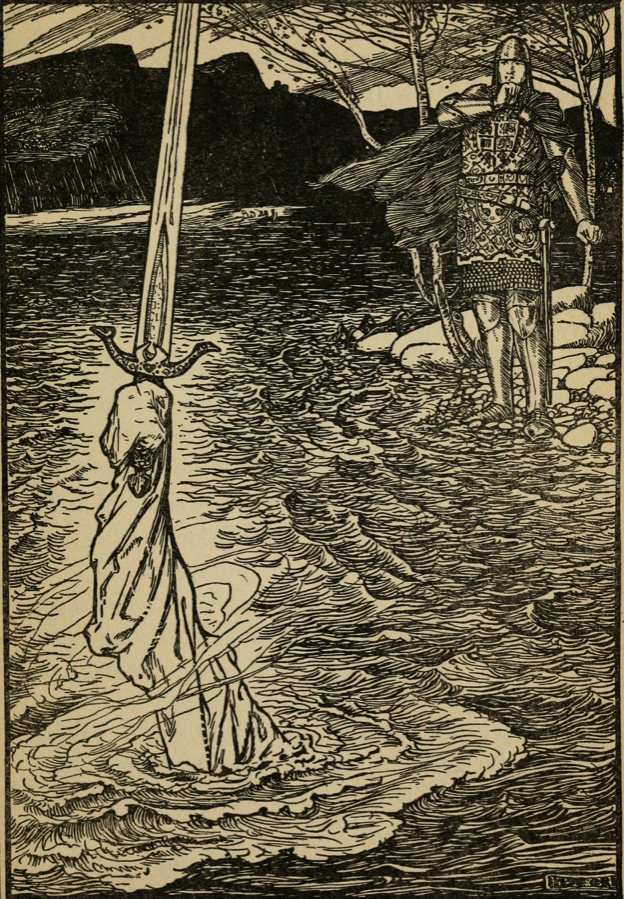

Of course, there is an Arthurian connection. Where you find the Grail, there too will you find Arthur and his knights.

The Knights of the Round Table and the Holy Grail

In the 15th century, Sir Thomas Malory mentions the spring in his Morte d’Arthur when Lancelot and others are said to have retired as hermits in a valley near Glastonbury. Some believe it was this site that he referred to.

The sacred water of the Chalice Well feels like the beating heart of the gardens that surround it, and visitors, like a protective shield.

There are four places where the water surfaces in the Gardens.

The first is one of the most striking features – the well cover in the form of the Vescica Piscis.

The Vescica Piscis is an ancient symbol that represents the intersection of the material and immaterial (Natural and Supernatural) worlds. Fitting for one of the traditional gateways to Annwn.

The Vesica Piscis well cover in the Chalice Well Gardens

The Chalice Well cover is made of English oak and wrought iron, and was designed after WWI by the architect and clairvoyant, Frederick Bligh Bond, who carried out the first excavations on Glastonbury Abbey.

The difference with this Vescica Piscis is that the circles are intersected by a sword, or bleeding lance, a Christian addition to this ancient symbol of power.

From the Well, the red water flows to the Lion’s Head where people can go to drink, or sit in quiet reflection while the water splashes onto a stone below.

Farther down the garden you come to a striking rich-red waterfall where the spring cascades into a pool where people can soak themselves in the healing water. This pool is another place of meditation known as Arthur’s Courtyard.

Filming at the Lion’s Head fountain in the Chalice Well Gardens

After that, the water flows past two ancient Yew trees, and a shoot of the Holy Thorn (yes, it survives!) into a pool shaped like the Vescica Piscis near where you enter the Gardens. The spring then flows away underground, beneath the Abbey and the pavement of Magdalene Street.

The red water’s healing sojourn above ground is fleeting, but for thousands of years it has brought people comfort, and peace.

Ancient yew trees in the Chalice Well gardens

Whenever I would visit Chalice Well and the gardens, my head pounding from a migraine, or the weight of a world of worries pressing me down, I would always leave feeling rejuvenated, calm, and optimistic.

Whether visitors are pagan, Wiccan, atheist, or Christian, or they adhere to some other system of belief, the Chalice Well is a place where people still believe in miracles, as they have done for thousands of years.

The Vesica Piscis pool in the Chalice Well Gardens

On the next part of our journey through Ynis Wytrin, or in insula Avalonia, we’re going to meet two very special giants.

They are tall, and broad, and green, and together they have stood the test of time. Their names are Gog and Magog.

The names of Gog and Magog will be well-known to Old Testament historians as evil powers to be overcome in the Book of Ezekiel (38-39), and in the New Testament Book of Revelation (20).

Gog and Magog also figure largely in the British foundation myths, mainly in the Historia Regum Britanniae of Geoffrey of Monmouth.

According to Geoffrey, when Brute, a descendant of the Trojan Aeneas, came to Britain in around 1130 B.C. he and his people fought a West Country giant(s) named Goemagot.

Gog and Magog in the Lord Mayor’s Show, London

There are many other tales and places around England and Ireland associated with the giants, Gog and Magog.

In Glastonbury it is different.

The giants of which I speak are two ancient and magnificent oak trees that are tucked away in this misty isle.

They are not war, or pain, or suffering. Gog and Magog represent the last of the great oaks of Avalon. They demand nothing of the wanderer, and yet they are revered.

The association with the giants only goes so far as the names of the trees, and their size.

The short walk to the oaks from the middle of Glastonbury town is one of the most beautiful walks in the area.

Cross Chilkwell Street, near the Abbey Barn, and head up Wellhouse Lane between the slopes of the Tor and Chalice Hill. Follow the foot path into the field where you will come to the ancient trail of Paradise Lane. At the bottom of Paradise Lane, you will find Gog and Magog waiting for you.

Gog and Magog on a wintry day some years back

These trees are ancient, no doubt. When they come into view, you are drawn to them as if to a comforting grandparent. You’ll find the odd ribbon tied to a branch, or a sheaf of wheat laid in offering among the sturdy limbs.

These two trees are friends to many in Glastonbury and beyond.

Gog and Magog are all that remain of an avenue of oaks that led to the Tor, and which was thought to be used as a processional way by the Druids in ages past.

Sadly, the avenue was cut down for farmland in 1906, and these two giants are all that remain.

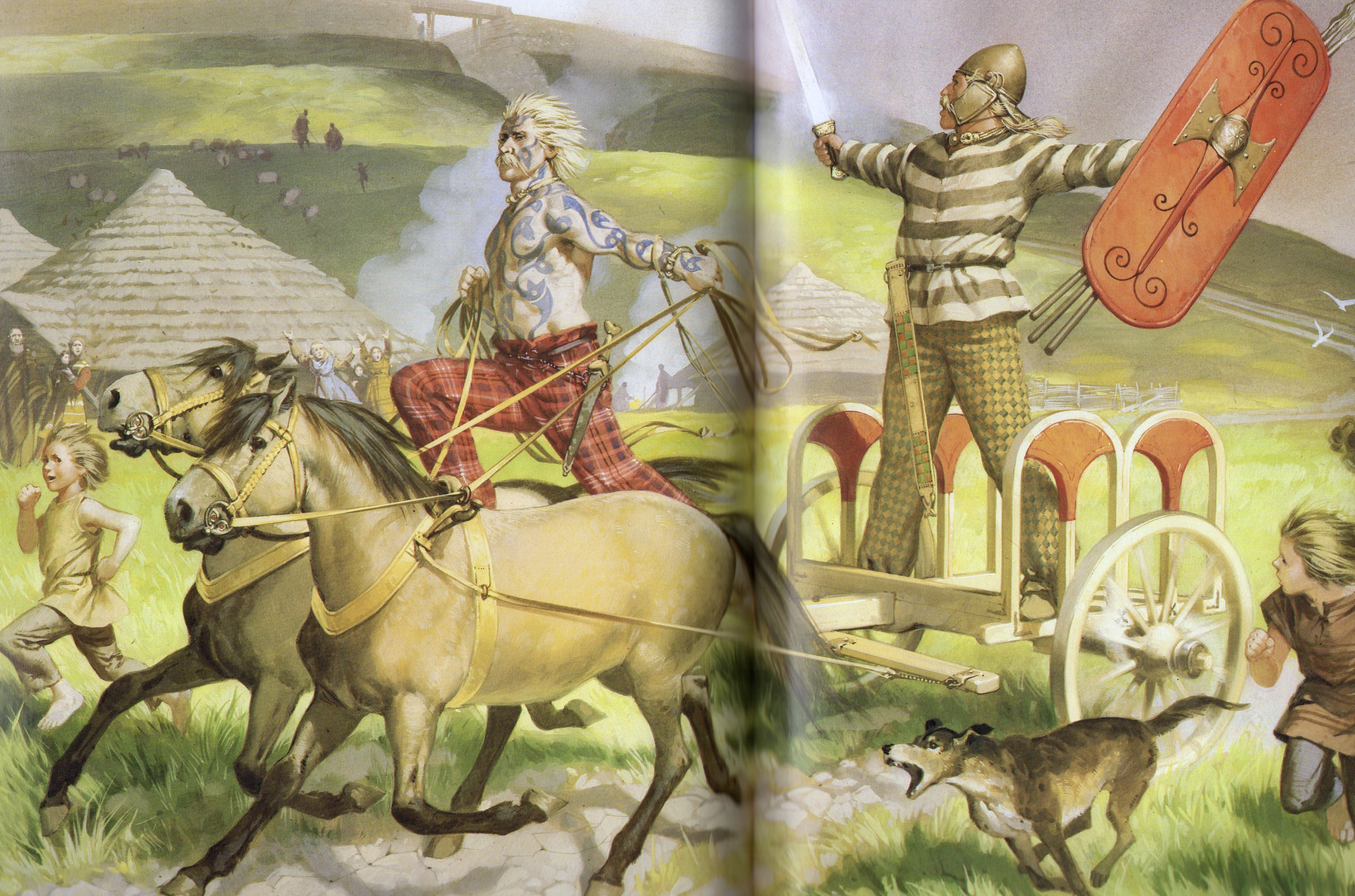

Oak trees like Gog and Magog were sacred to worshippers of the Great Mother, and later the Druids. Before Rome and mass farming came to Britain, the whole of the south of Britain was covered in forests from Hampshire to Devon.

Oak groves were sacred, the sites of the Goddess’ perpetually burning fires and the rites of the Druids who used oak leaves in their rituals.

View of the Tor from Paradise Lane, on the way to Gog and Magog

The sanctity of the oak was not relegated to Celtic Europe either, but also goes back to ancient Greece. At the sanctuary of Zeus at Dodona, priests would glean the will of Zeus from the rustling of the leaves in the sacred oak groves.

At Glastonbury, Gog and Magog would likely have seen many a ritual or procession.

If they could only speak in a way we could understand, I’m sure they would have some fantastic tales to tell.

Taking the walk from town, past the Tor, and down Paradise Lane to see Gog and Magog was always one of my favourite walks. Because there are no roads nearby, the sound of cars is absent, and all you can hear is the chirruping of birds and the whisper of the wind as it blows across the Somerset levels.

When I returned there to do research for Isle of the Blessed, my feet found their way there once more, whisking through the dry field grass, or squelching through the mud, until I caught that first glimpse of the two giants.

“It’s good to see you again, after so long…” I thought, feeling a great comfort and sense of gratitude.

Visiting the friendly giants

From my days in insula Avalonia, I can still recall refreshing walks along the crest of Wearyall Hill, along the dragon’s back of the Tor, and down Paradise Lane to Gog and Magog.

However, there is another place of peace, a sanctuary in the middle of town, nestled between Wearyall Hill, Chalice Hill, and the Tor. It is Glastonbury Abbey.

The Abbey grounds, like other sanctuaries in town, are a place to get away to. You have to pay to get in, but once you walk through the arch, past another descendent of the Holy Thorn, and onto the green lawns surrounding these magnificent ruins, you are set to experience a whole new aspect of Glastonbury.

The ruins of Glastonbury Abbey from the area of the main altar

The ruins of what was once one of the largest abbeys in England rise up from the soft ground, sentry-still, surrounded by mist. ‘Majestic’ is a word I would use to describe the ruins, and ‘sad’. When you see the model of what the place looked like at its height of power and prominence, you understand.

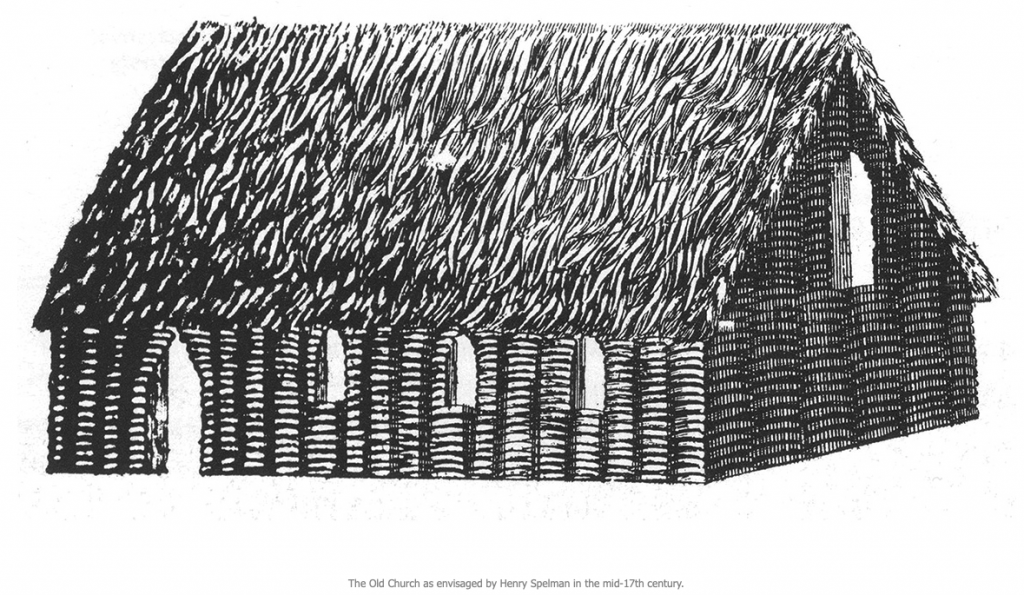

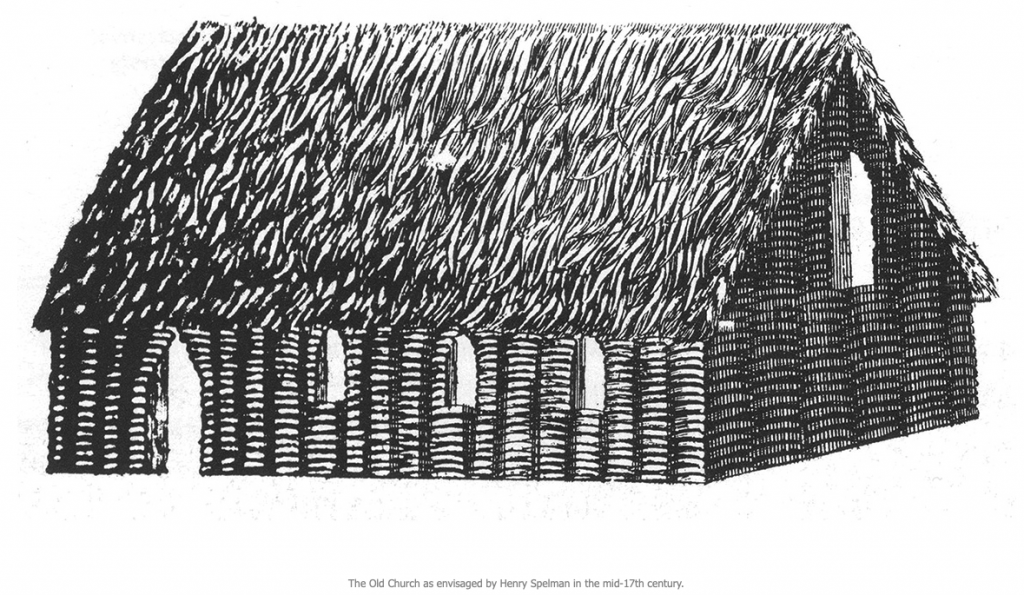

Glastonbury abbey was not always such a soaring monument of Christianity. The lovely ruins that can be seen today are a medieval creation, the remains of which date from the twelfth to sixteenth centuries. But the place itself is said to be the site of the first Christian church and oldest religious foundation in the British Isles.

Model in the abbey museum of what Glastonbury Abbey used to look like before the Dissolution of the Monasteries.

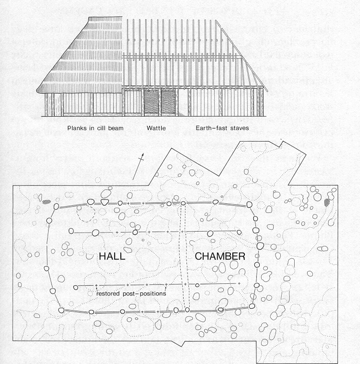

According to tradition, Joseph of Arimathea and his followers built a wattle church on the site on land he was given by the local king, Arviragus (possible ruler of South Cadbury Castle at the time) around the middle of the first century A.D.

Circa A.D. 160, two Christians named Faganus and Deruvianus are supposed to have added a stone structure on the site of what is the Lady Chapel. It is here that there is an ancient well dedicated to St. Joseph.

St. Joseph’s Well in the crypt of the Lady Chapel

In the early days of Christianity in Britain, this first chapel and the well were the predecessors of the magnificent ruins of the abbey we see today. The Lady Chapel was the site of the first Marian cult in Britain, and in the words of Geoffrey Ashe “there is no rival tradition whatsoever. When all of the fantastic mists have dispersed, ‘Our Lady St. Mary of Glastonbury’ remains a time-hallowed title.”

In one of the Welsh Triads, Glastonbury is given the distinction of having a ‘perpetual choir’.

It was a place that Christians gravitated to. Indeed, several Celtic saints are said to have come here, including St. Bridget, St. David, St. Columba, and even St. Patrick whom some stories name as the first abbot of Glastonbury.

Lady Chapel c 1900 (Wikimedia commons)

Walking the grounds of Glastonbury Abbey is a contemplative activity, like so many other spots in insula Avalonia.

It is supremely peaceful and there are all manner of flora in the gardens to add to the calm. Great trees shiver overhead when a breeze blows into town from across the Somerset levels.

You can stroll the scant remains of the cloisters and up the nave with the abbey’s stone titans looming over you. In a couple spots, you can lift a wooden cover to reveal some of the colourful tiles of the medieval abbey floor.

Surviving tiles of the Abbey’s medieval floor

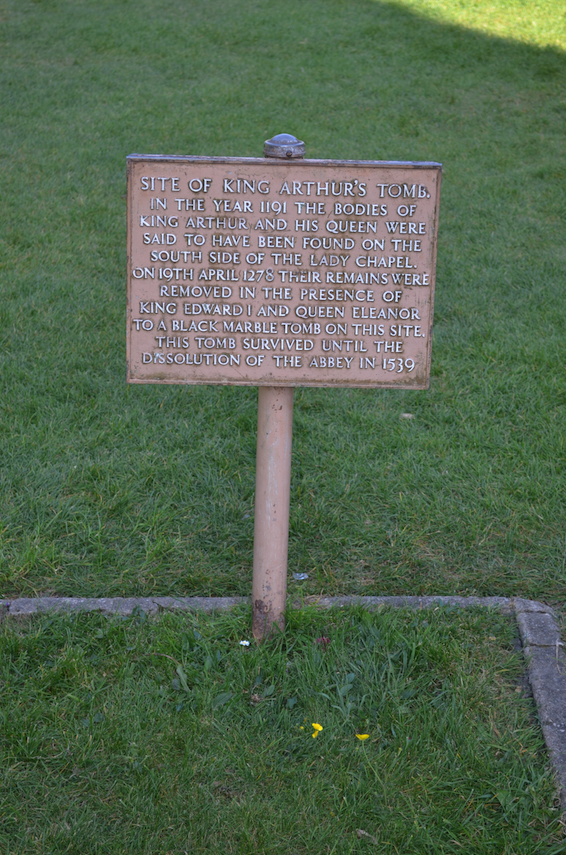

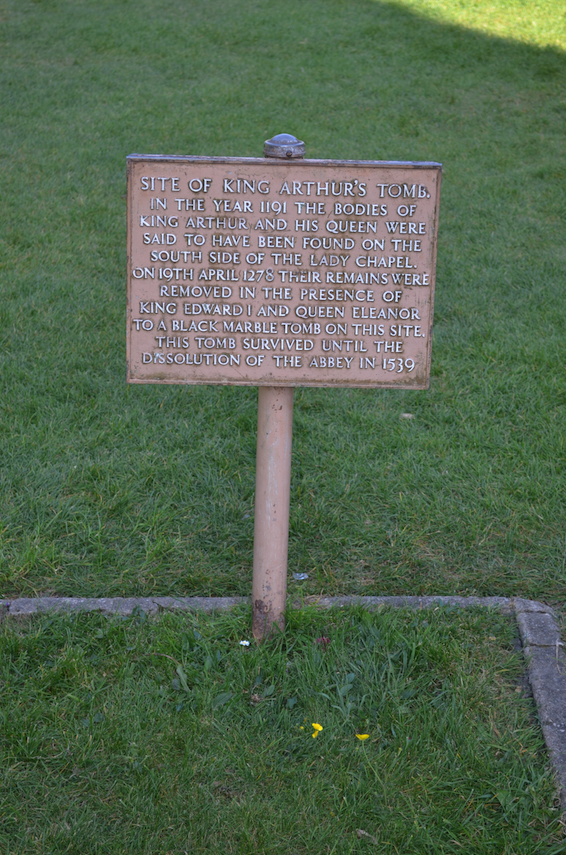

Then, toward the transept, you come to an unassuming outline in the grass with a plaque marking it.

This is where you meet with one of Glastonbury Abbey’s most mysterious connections.

In 1184 a fire ravaged the abbey and the monks needed to rebuild. Around the time of the fire, a Welsh bard is supposed to have revealed to King Henry II that King Arthur himself was buried within the abbey grounds.

The king passed this information on to the Abbot of Glastonbury who later ordered excavations to be carried out. In 1191, it is said that the monks found the bones of a man and a woman in a hollowed out tree trunk who were none other than Arthur, and his queen, Guinevere.

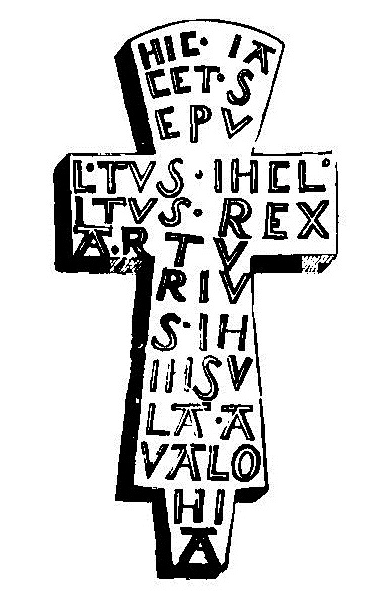

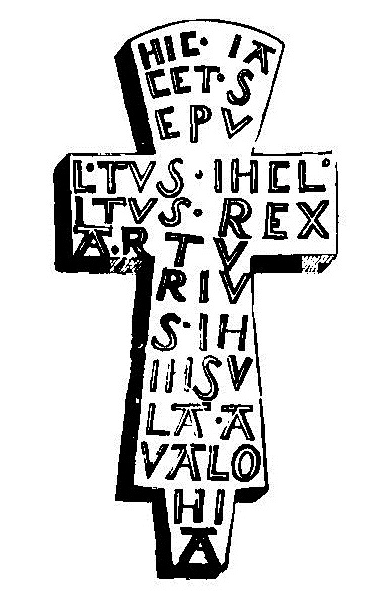

With the remains was a lead cross with the words ‘Hic Jiacet Sepultus Inclytus Rex Arturius in Insula Avallonia’ which translates as ‘Here lies buried the renowned King Arthur in the Isle of Avalon’.

Spot where Arthur and Guinevere’s bones are said to have been discovered

The Elizabethan antiquarian, William Camden, did a sketch of the Arthur cross in the early 17th century.

A lot of doubt has been cast on the monks’ discovery with many believing that it was a hoax created by the monks to boost tourism through pilgrimage. The remains were treated as relics and later moved within the abbey during the reign of Edward I in the early 13th century.

Sketch of the ‘Arthur Cross’ discovered in the burial beside the Lady Chapel

It is important to note that the archaeologist who excavated the abbey in the 1960s, Dr. Ralegh Radford, indicated that the monks’ story might not have been that far-fetched, and that there was indeed a person of great import from the correct period buried in the graveyard just south of the Lady Chapel.

As with all things in Glastonbury, belief is always a part of the great equation.

There are other buildings associated with the abbey too, including the Abbot’s Kitchen where the Benedictine brothers would have prepared meals, and the Abbey Barn which is now home to the Somerset Rural Life Museum.

The site is lovely and inspiring. Tradition on the abbey grounds goes back ages to the very roots of Christianity in Britain and beyond, and this Christian presence comes as a surprise to the Romans who find themselves in Ynis Wytrin in Isle of the Blessed.

17th century sketch of what Joseph of Arimathea’s original chapel might have looked like

As I would sit on a bench, listening to the birds and the breeze, gazing upon the ruins, I would imagine St. Joseph arriving with his followers and picking out the spot for that first chapel. Perhaps they had something in common with the druids and priestesses of the goddess who might have already been there? Perhaps a common yearning for peace and truth?

It is sad that Henry VIII robbed us of the physical beauty of Glastonbury Abbey in the great Dissolution. The last abbot was dragged to the top of the Tor and beheaded by the King’s henchman, Cromwell.

For this place to function peacefully and unmolested from its earliest time, through Saxon incursions and Norman invasions, speaks to its agreed importance over the ages.

The majesty of this place may lie in ruins now, but its spirit and mystery certainly remain intact.

The Lady Chapel today

I hope you’ve enjoyed this post on Glastonbury and The World of Isle of the Blessed as much as I enjoyed researching, revisiting, and writing about it in the novel. It was especially inspiring to write a story set in a place people of various beliefs lived together, and then to send my Roman protagonist into their midst.

What would a Roman think of a place where pagans and Christians, including Druids, lived together in peace and harmony?

Well…to learn that, you will have to read the book.

Join us next week for Part IV of The World of Isle of the Blessed when we will be taking a look at the main historical players in the imperial court in Britannia.

Thank you for reading.