I had an urge this week to write about doing laundry in ancient Rome.

Why?

Because our laundry machine broke down and we are waiting to get it repaired.

As with many things, history geek that I am, it reminded me of ancient history. When I need to clean some piece of clothing without a machine, I use the sink with fresh running water and soap. If you lived in the 19th century, you might have used an old fashioned wash-board with some lye soap – plunge and scrub, plunge and scrub!

But the Romans didn’t have soap, or wash-boards.

So what was a Roman to do when their tunica or stola needed a good cleaning?

Oddly enough, they did not wash their clothes at home.

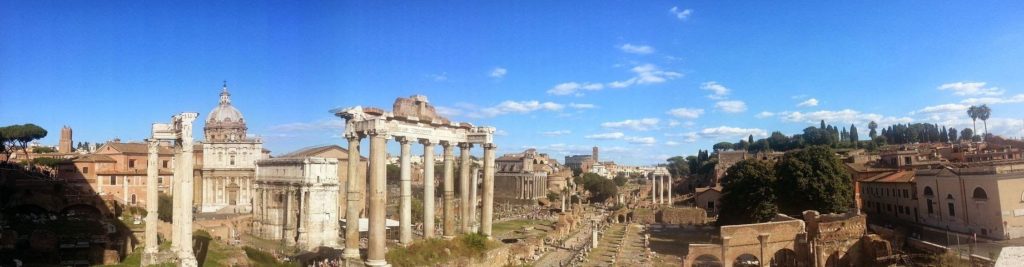

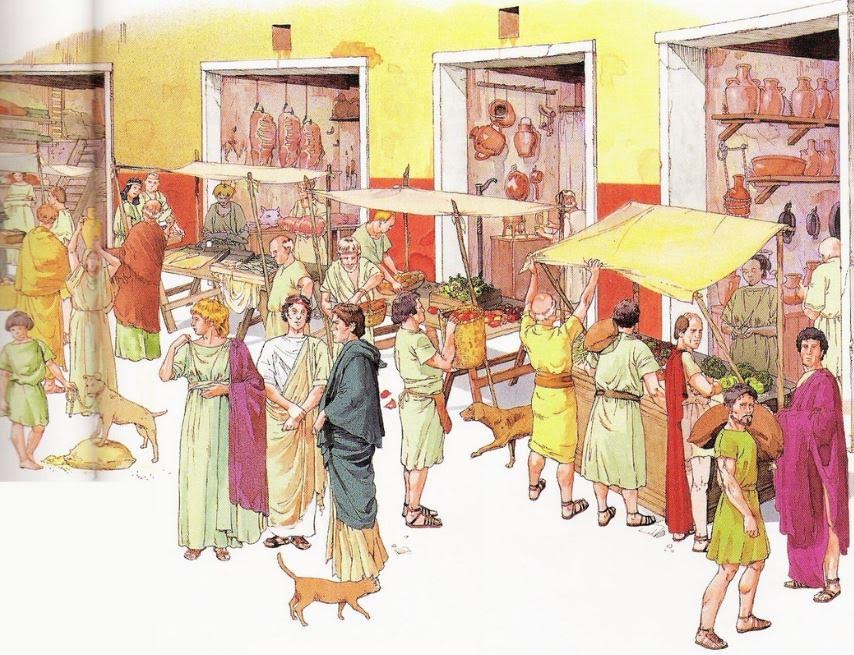

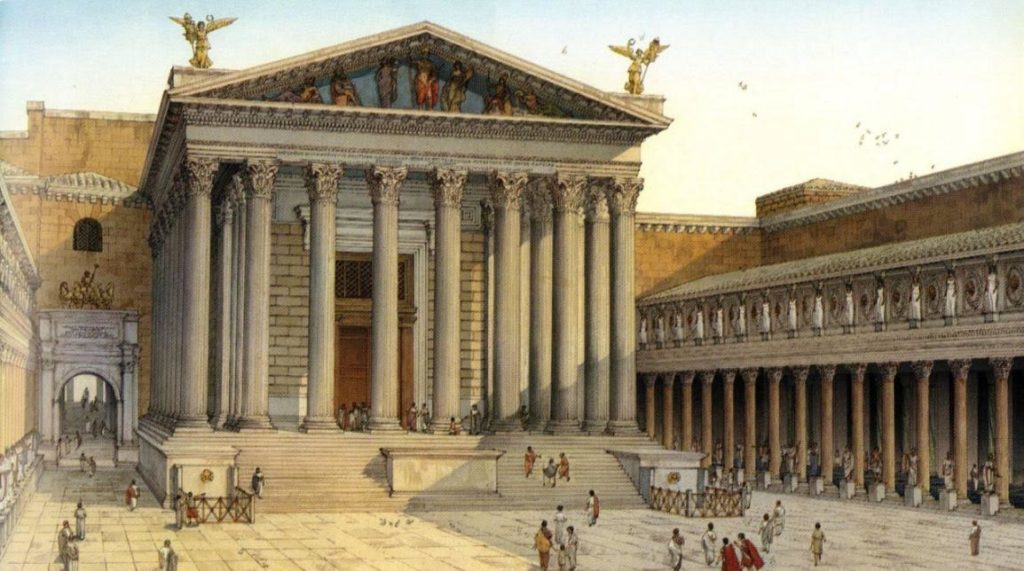

They took them to a fullonica, the ancient version of a laundry mat or dry cleaners.

Fullers, or fullones, were washers and scourers of clothing and new cloth, and they did a pretty good business in ancient Rome.

I mean, those streets were dirty! And with all the olive oil and garum stains on their clothing, their clothes would have needed a good scrubbing.

There were apparently many fullonicae in ancient Rome and other towns such as Pompeii and Ostia, but how did fullones get the clothes of their fellow citizens clean without any soap?

Why, with human pee of course!

Ok, I’m sensationalizing this a bit, but urine was certainly a part of the process.

Basically, there were three steps to doing laundry properly in the Roman world.

First, the clothing or new cloth had to be washed by the fuller, the fullo.

This was done by putting the clothes in a small tub full with a mixture of water, nitrum or fuller’s earth (known as creta fullonia), some alkali elements, and of course, urine. Water and urine appear to have been the main ingredients of this ancient detergent.

But how did a large prosperous fullonica get enough urine to do the laundry of Rome or Ostia? Well, they placed jars on street corners around the neighbourhood where they operated so that passersby could make a…donation.

I’m guessing the jars near tabernae might have been the most useful. You have to feel for the poor sod whose job it was to go and bring the full jars of urine back to the fullonica through the busy streets of Rome. Maybe people gave him a wide berth so as not to get splashed?

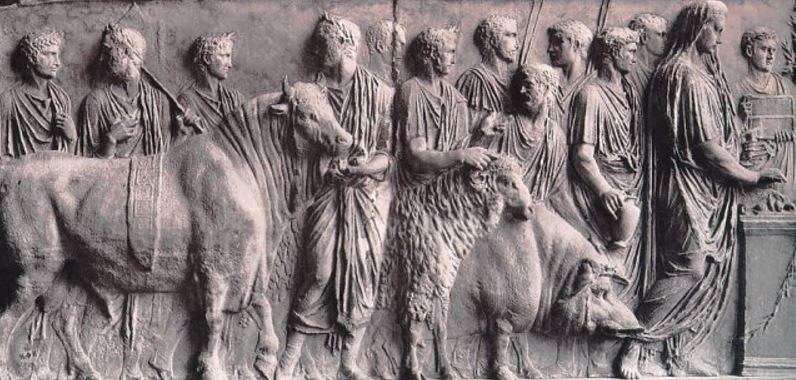

At any rate, once the clothes were in this cleaning mixture, the fuller would get in barefoot and stomp away, over and over, until the clothes were scrubbed of oil, dirt, and grease. This little dance was known as the saltus fullonicus, or the ‘fuller’s jump’.

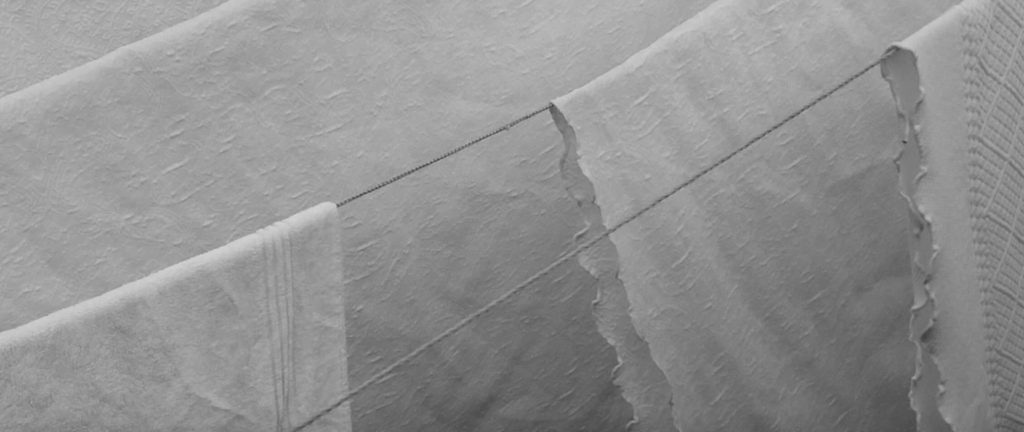

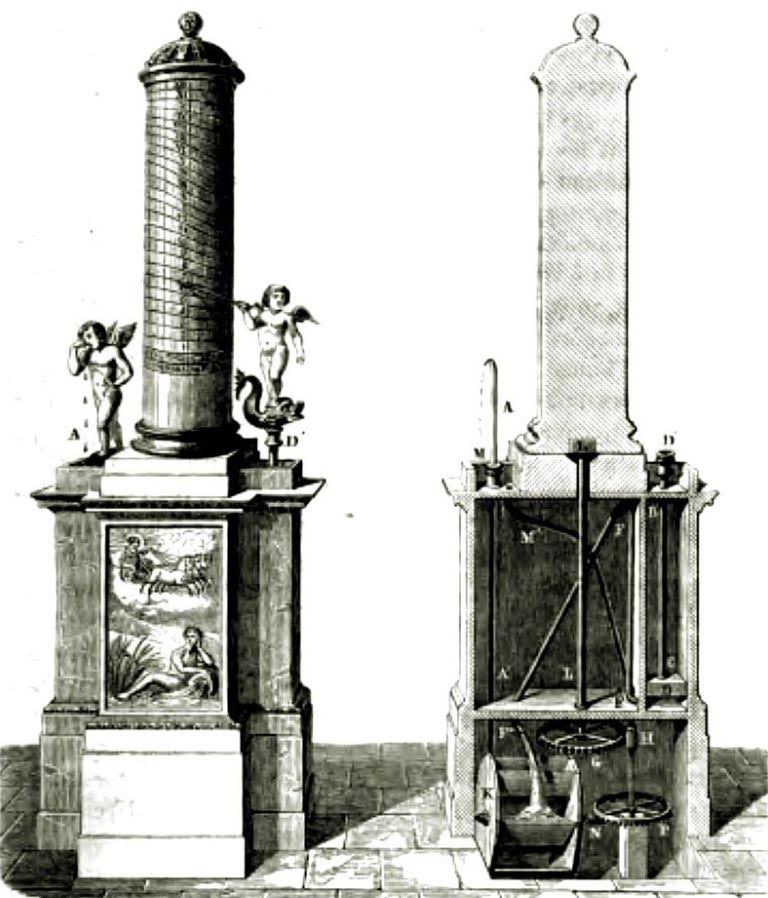

The next step in the process was to rinse the clothing or cloth. This was done in a series of larger, interconnected wash basins into which poured fresh running water from the town water supply.

The fullo would start at the the dirty end, near the spout where the water exited, and then move up the basins toward the clean end where the water came out.

The final stage involved brushing the clothing (usually wool) with either thistly plants, or the skin of a hedgehog (insert sad face here). They were then hung to dry on a large upside-down wicker basket work with sulphur placed beneath it so as to allow the fumes to whiten the clothes.

High-end fullones, as part of this final stage in the process, might also have rubbed in cimolian, a fine white earth that was supposed to whiten the garment even further.

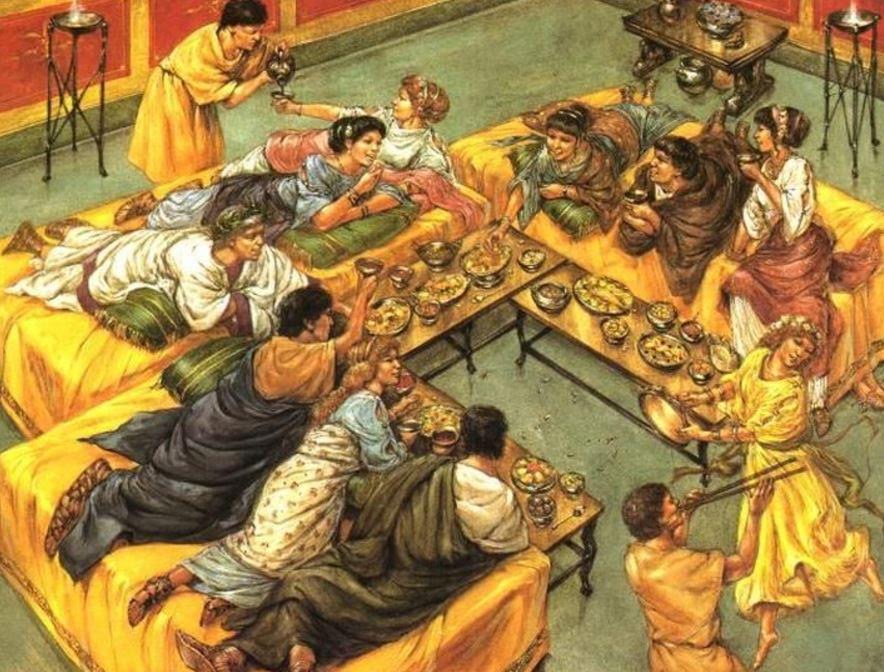

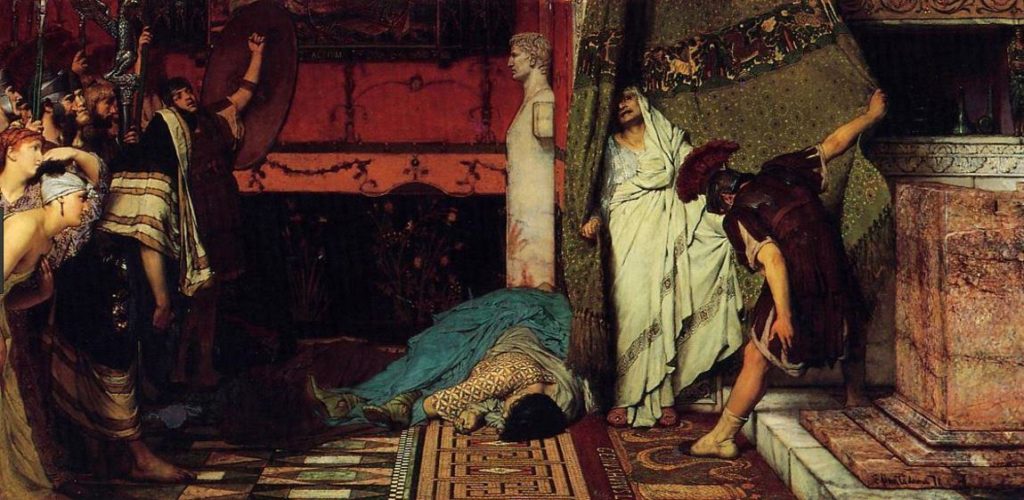

Once this was all done, your toga was ready to wear to your next imperial banquet!

Caesar and Vorenus had to clean their togas somewhere! (screen shot from HBO’s fantastic series, ROME)