Greetings Readers and History-Lovers!

Welcome back to The World of An Altar of Indignities, the blog series in which we share the research for our latest novel, An Altar of Indignities: A Dramatic and Romantic Comedy of Ancient Rome and Athens.

If you missed the first post on drama and theatres in ancient Athens, you can read that by CLICKING HERE.

In Part II, we’re going to be taking a brief look at travel and transportation in the Roman Empire. As we shall see, this is something the Romans did really well!

We hope you enjoy!

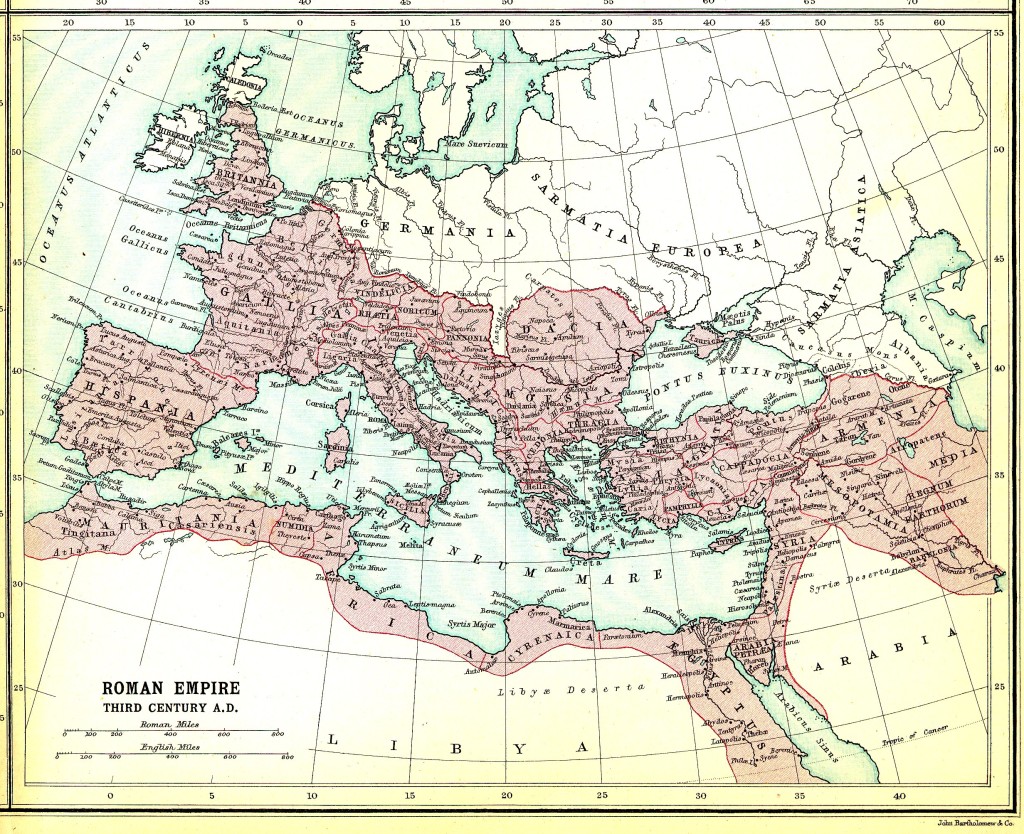

Map of the Roman Empire at its greatest extent (Oxford Research Encyclopedias)

The Etrurian Players – the tumultuous theatre troupe of our story – regularly travel the Mediterranean Sea to get to the location of their next performance, be it in the cities of Iberia, the great polis of Alexandria or, as is the case in this story, the city of Athens where theatre was born.

But how easy is it for The Etrurian Players to get from one place to another while on tour? How did ancient Romans, and Etrurians for that matter, get about?

Travel is something that we take for granted today. We decide we need to get somewhere, and we just go, be it nearby, or over a great distance across oceans and continents. We often take it for granted in fiction too. Characters often need to get from point A to point B, and it happens.

But in the ancient world, travel wasn’t so easy. It required planning, and it took time.

There were also many factors involved such as destination, budget (not unlike today), mode of transportation, and time of year. Unless one was a soldier, or merchant, or someone wealthy, chances are that you might never have left your community or indeed your Etrurian latifundium!

So, when people did travel in the Roman Empire, how and why did they do so?

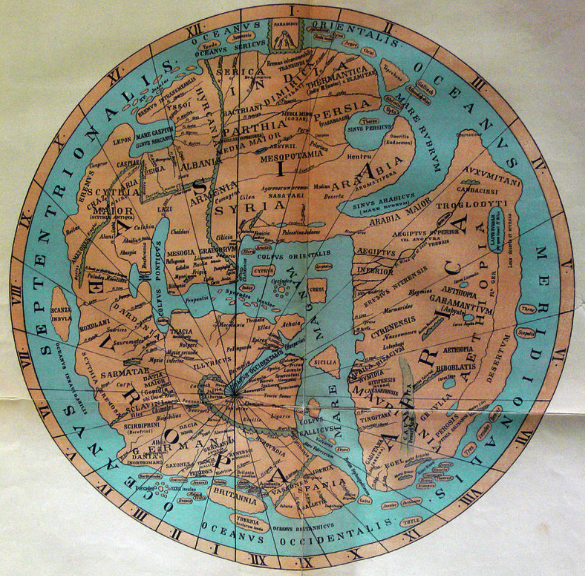

Ptolemy’s world map, reconstituted from Ptolemy’s Geography, circa AD 150, in the 15th century, indicating Sinae, China, at the extreme right. (Wikimedia Commons)

First off, we should probably discuss maps. We use maps today, and the Romans had maps. Geography was important, especially if you were planning a large scale invasion or military campaign, or even surveying for a new settlement. Not many maps from the Roman period survive, but copies of maps were made from originals. Sometimes they were even rendered in paintings or mosaics.

Maps, geography and cartography are mentioned by some ancient authors such as Strabo, Polybius, Pliny the Elder, and Ptolemy. We also know that large wall maps of the world were commissioned by Julius Caesar, and then by Agrippa, during the reign of Augustus.

Much of our knowledge of place names and geography from the Roman world comes from what are called ittinerarium pictum which were travel itineraries accompanied by paintings. Perhaps the most well-known of these is Ptolemy’s Geography which included six books of place names with coordinates from around the empire, including faraway places such as Ireland and Africa.

Another source is the Ravenna Cosmography. This was a compilation of documents by a cleric at Ravenna around 700 C.E. This particular source gives lists of stations, river names and some topographical details as far away as India.

Details of a map based on the 11th century Ravenna Cosmography (Wikimedia Commons)

The Notitia Dignitatum is a late Roman collection of administrative information which included lists of civilian and military office holders, military units and forts. The maps that accompanied this were medieval, but it is believed that they were derived from Roman originals of the fourth and fifth centuries C.E.

Perhaps the most important surviving example of an itinerary, however, is the Itinerarium Antoninianum, the ‘Antonine Itinerary’, which was a collection of journeys compiled over seventy-five years or more and assembled in the late 3rd century. It describes 225 routes and gives the distances between places that are mentioned. Some believe it was probably used for travel by emperors or troops. This particular source also included a maritime section with sea routes entitled Imperatoris Antonini Augusti itinerarium maritimum. The longest route in this itinerary appears to represent Emperor Caracalla’s trip from Rome to Egypt in about 214-215 C.E, about ten years after An Altar of Indignities takes place.

Map of Roman Britain based on the Antonine Itinerary, plotted by William Stukeley in the 1700s using the Itinerary as its source. (University of Kent)

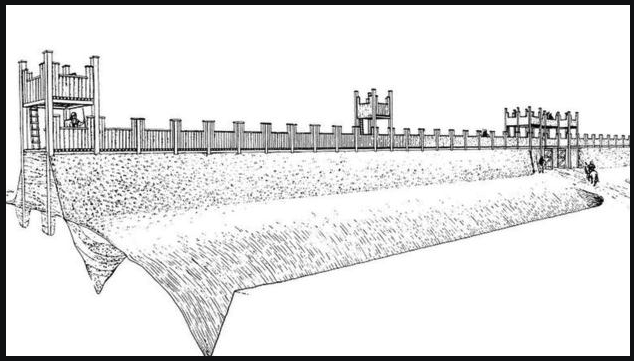

Next, one cannot discuss travel in the Roman Empire without talking about roads.

There is a reason the expression ‘All roads lead to Rome’ exists. It was true, at least for a time. This is believed to have originally referred to the milliarium aureum, the ‘golden milestone’ near the temple of Saturn in the Forum Romanum, from which all distances were measured. It is believed that distances to specific cities or settlements were written upon it.

Part of the Via Egnatia near Kavala, Greece

When it comes to roads, Rome was the best. In fact, Roman roads forever altered the empire and travel itself. Not only did Roman roads make troop movements much easier – with the troops building the roads themselves! – but they also opened up parts of the empire to trade and further settlement. They spread out from Rome like a titanic spider web connecting the eternal city to the farthest outposts.

There were also various types of road too, not just the broad, paved roads upon which vehicles and legions could travel. There were also small tracks, causeways, narrow streets, embanked roads or strata, lanes and more. Whether you were crossing the world, or crossing a settlement, roads of all types were useful.

The Roman empire in the time of Hadrian, showing the network of main Roman roads. (Wikimedia Commons)

Of course, with Roman roads, came Roman bridges over rivers that might have added days to a journey in order to reach a suitable crossing point. Travel was shortened in many ways by using Roman roads.

Now that we know how important roads were to the Roman Empire, how did people travel upon them?

When it came to the legions, marching was the order of the day for most troopers, and the average Roman soldier, fully laden, could travel up to 25 Roman miles in one day. For the average person living within the bounds of the empire, walking was also the norm. This mode of travel was slower, to be sure, though roads made it much easier.

Apart from walking, there were of course other, faster modes of transportation such as by horse, pack animal, two-wheeled cart, and four-wheeled wagon. Obviously, these required one to have the funds to own or rent such animals and vehicles, but they did greatly cut back on the travel time.

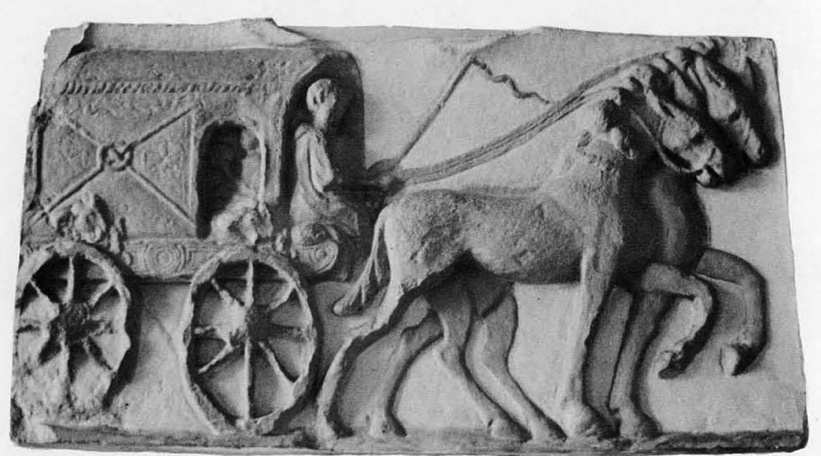

A Roman relief showing a four-wheeled, covered wagon (photo – Penn Museum)

The time of year and the weather were obvious factors when it came to travel upon roads, but also when it came to water routes open to travellers such as by river, open sea, and coastal sea travel.

When it comes to seafaring, the Romans had no such tradition until after the wars with Carthage which forced them to come to terms with the need for a navy. With the creation of that navy, Roman troops could be moved more quickly from Rome to Africa, for instance.

The other reason for travelling by sea or waterway was, perhaps more importantly, trade. The Roman Empire at its peak was vast and varied, and there was an enormous trade network that ensured raw materials such as lead and marble made it to construction sites as far away as Britannia, or from there to Rome itself. Perhaps the officers on Hadrian’s wall missed their favourite garum produced in Hispania, or wine from their family’s Etrurian estate?

A Roman cargo ship, or ‘corbita’ (image: naval-encyclopedia.com)

To transport large amounts of goods where they needed to be at the farthest reaches of the empire, or to the heart of Rome, sea transport was the way to go, and massive ports such as those at Ostia, Carthage, Alexandria, and Piraeus were constantly alive with trade.

There were various types of ships, both commercial and military, but despite the efficiency of this mode of transport, it was even more restricted by the seasons and weather than travel over land. Sea travel could be absolutely treacherous, and the number of ancient shipwrecks that dot the coasts of the former Roman Empire are a testament to this.

The wreck of a 110-foot (35-meter) Roman ship, along with its cargo of 6,000 amphorae, discovered at a depth of around 60m (197 feet) off the coast of Kefalonia. (Photo: CNN)

If you want to read more about the various types of ships used in the Roman Empire, be sure to check out the Naval Encyclopedia page HERE.

As mentioned before, we often take travel for granted in the modern world, but it cannot be overstated how important travel was in the Roman Empire, nor how much Roman road and ship building opened up the world and the economy of Europe at the time. Yet another thing the Romans did for us!

Modern aerial view of the three harbours of the port of Piraeus, the port of Athens

We hope you’ve enjoyed this brief post about travel and transportation in the Roman Empire.

If you’re interested in taking a look, one particular tool that was especially useful when researching and writing An Altar of Indignities was Orbis: The Stanford Geospatial Network Model of the Roman World. This special GIS tool uses ancient and modern source information to accurately create itineraries for travel between destinations in the Roman Empire, taking into account mode of transport, time of year, and whether travelling by land or sea. You can check that out HERE.

Stay tuned for Part III in The World of An Altar of Indignities in which we will be taking a look at the Roman monuments of ancient Athens.

Thank you for reading.

There are more posts coming in The World of An Altar or Indignities, so make sure that you are subscribed to the Eagles and Dragons Publishing Newsletter so that you don’t miss any of them. When you subscribe you get the first prequel book in our #1 best-selling Eagles and Dragons series for FREE!

If you haven’t yet read any books in The Etrurian Players series, we highly recommend you begin with the multi award-winning first book Sincerity is a Goddess: A Dramatic and Romantic Comedy of Ancient Rome.

In celebration of drama in the ancient world, be sure to check out our ‘Ancient Theatre’ Collection in the Eagles and Dragons Publishing AGORA on Etsy which features a range of ancient theatre-themed clothing, glassware and more! CLICK HERE to browse.

An Altar of Indignities: A Dramatic and Romantic Comedy of Ancient Rome and Athens is now available in ebook, paperback and deluxe hardcover editions from all major online retailers, independent bookstores, brick and mortar chains, and your local public library.

CLICK HERE to buy a copy or get ISBN# information for the edition of your choice.

Brace yourselves! The Etrurian Players are back!