Some of the most timeless stories in western literature are about the heroes of ancient Greece.

For millennia people have been inspired by Perseus, Jason and the Argonauts, Theseus, Achilles and Odysseus. Many an ancient king and warrior has tried to emulate the actions and personae of these heroes, and even claimed descent from them.

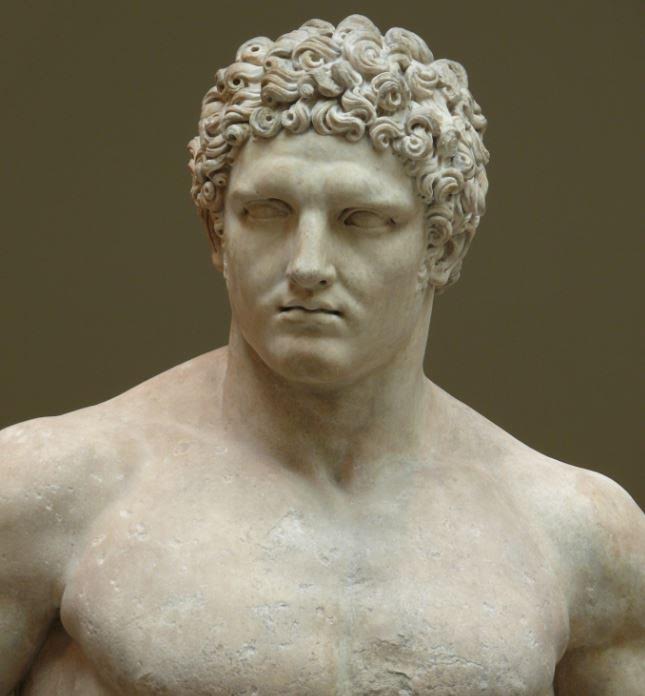

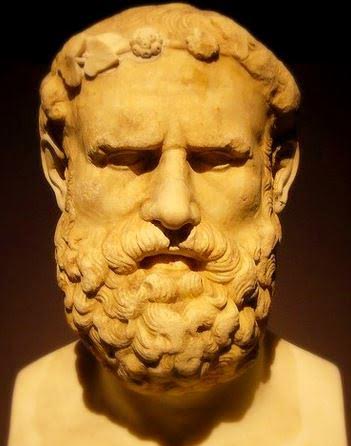

Far and away, the greatest hero of all was Herakles.

There are so many stories related to Herakles (‘Hercules’ of you were Roman) in mythology that it’s impossible to cover all of them in a simple blog post. A book would be required for that.

So, this post is going to be the first in a two-part series on the hero. There are countless triumphant deeds associated with Herakles, but for our purposes here, I’m going to cover the most famous of all – The Twelve Labours.

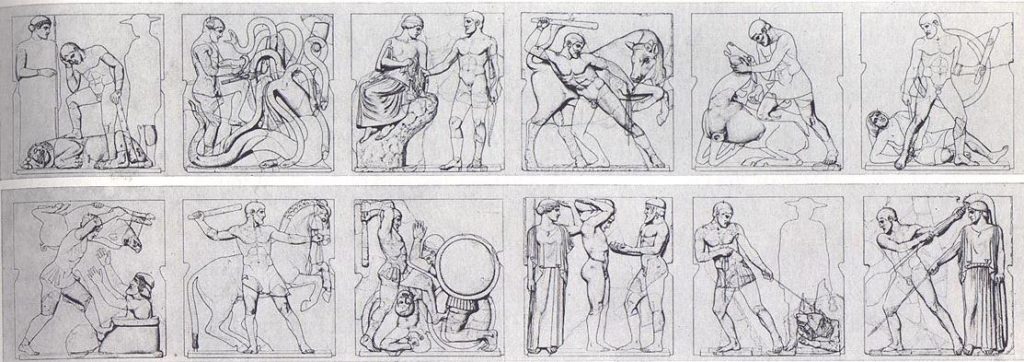

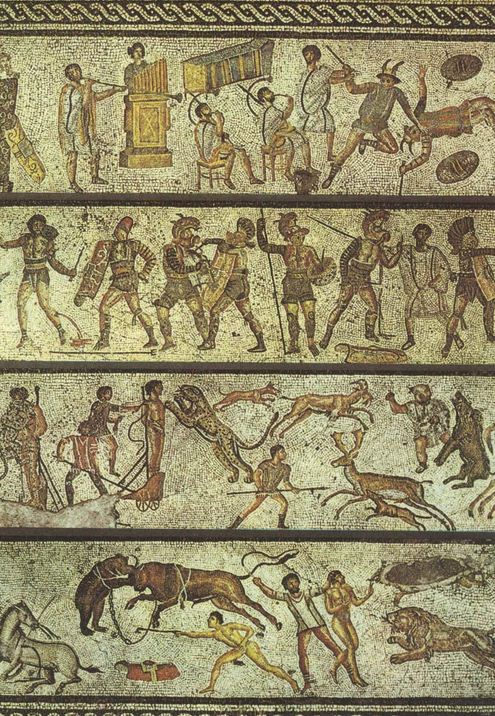

The Twelve Labours of Herakles have been the subject of art, sculpture and song for ages. Their portrayal decorated the ancient world from the images on vases to the metopes on the Temple of Zeus at Olympia. In our modern age, we’ve seen him in comics, television shows, and movies.

Aerial view Tiryns

But who was Herakles? Where did he come from?

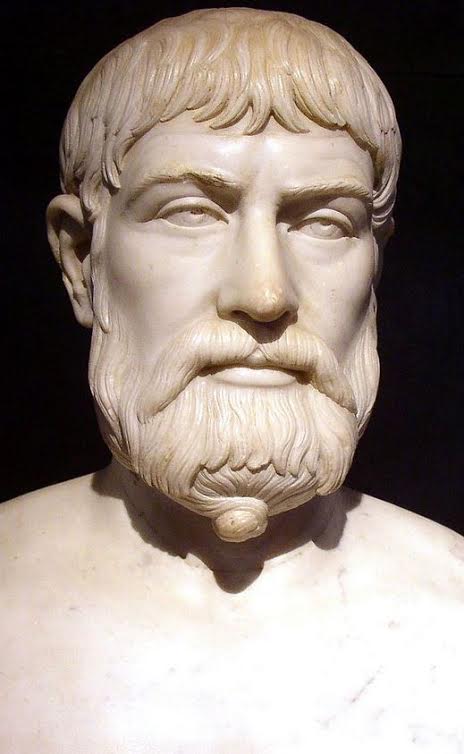

Herakles was born in the city of Thebes. He was the son of Zeus who begat him on Alcmene, a granddaughter of Perseus and Andromeda. Zeus came to her in the guise of her mortal husband, Amphitryon, and so Herakles was born.

From the beginning, Herakles showed that he was not a ‘normal’ person. Out of jealousy, Hera, Queen of the Gods and wife of Zeus, sent two snakes to kill the baby Herakles in his cot. Herakles strangled the snakes with his bare baby hands.

When he was 18 years of age, Herakles began to really make a name for himself by slaying a lion on the slopes of Mount Cithaeron after hunting it for fifty days. During that time, he stayed with the king of Thespiae who was so impressed with the youth that he had him beget children on all fifty of his daughters.

Herakles was a man of extreme prowess, deeds, emotion and appetites.

King Creon of Thebes rewarded Herakles for helping him against his enemy, Erginus, king of the Minyans by giving him the hand of his daughter Megara, with whom the hero had several children.

This is where things sour for the young hero. After all, this is a Greek story, and tragedy is never far behind to bring even the mightiest of heroes back to Earth.

Temple of Apollo at Delphi

Hera stepped in to afflict Herakles with madness, causing him to kill his wife and children. When his sanity returned, he was overcome with grief and went to the Oracle at Delphi for advice.

The Oracle told him to go to Tyrins and serve its king, Eurystheus, for twelve years, as punishment for his brutal crime. He had to complete all tasks set for him by the king, and this is the origin of The Twelve Labours.

It’s curious that the name ‘Herakles’ means ‘Glory of Hera’, since she persecuted him so much throughout his life. Then again, perhaps as Hera is the root cause of his Labours, his triumphs reflect on her?

I – The Nemean Lion

This first labour is probably his most famous, and takes us to the ancient land of the Argolid peninsula. The lion that was terrorizing the hills about Nemea had skin that was impenetrable to weapons and so Herakles, when he faced it, choked it to death with his brute strength and then used the claws to skin it. It’s this skin, which he used as a hooded cloak, that the hero became known for in art. If you see someone with a lion’s head on their own, it’s likely Herakles, or someone trying to emulate him.

Region of Nemea

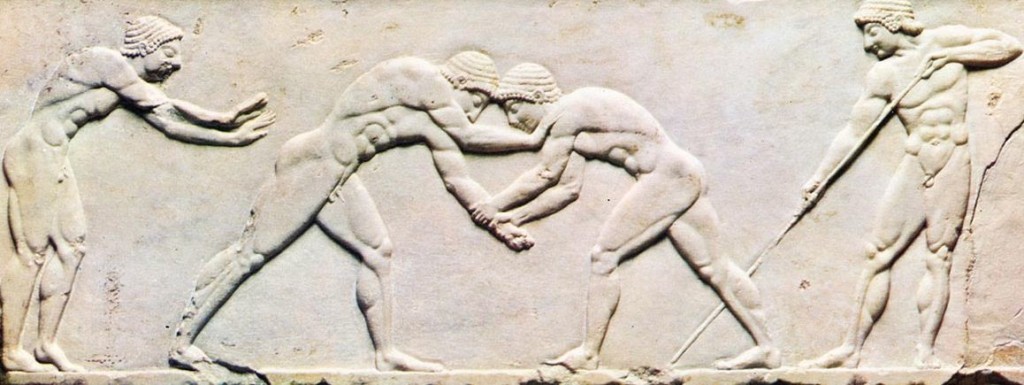

As a side note, Nemea was thereafter the site of the Nemean Games, one of the four sacred games of the ancient world, which also included the Isthmian Games, the Pythian Games, and the Olympic Games. You can read more about ancient Nemea by CLICKING HERE.

II – The Lernean Hydra

When he faced the Hydra in the Peloponnesian swamps of Lerna, it’s a good thing that Herakles brought along his nephew and companion, Iolaus. Facing the monster, he discovered that when he cut one head off, two more grew back in its place. And so, after each head was cut, Iolaus would cauterize the stump before it could grow again. When the Hydra was dead, Herakles dipped his arrows in the blood which was poison, even to Immortals. These arrows would come in useful in later episodes of the hero’s life.

Heracles fighting the Hydra

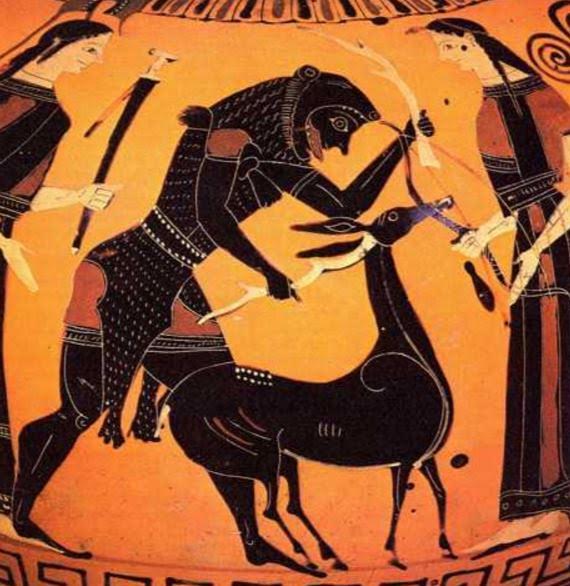

III – The Ceryneian Hind

Eurystheus, this time, thought he would set Herakles against Artemis with this third labour by telling him to capture a deer with golden horns that was sacred to the goddess. But Herakles pursued the hind for a whole year until he finally captured it and brought it before Eurystheus who, by this time, was always hiding in a jar whenever his cousin would return. The hind was allowed to go once it was brought before the king and so Herakles was able to avoid Artemis’ wrath.

The Cyreneian Hind

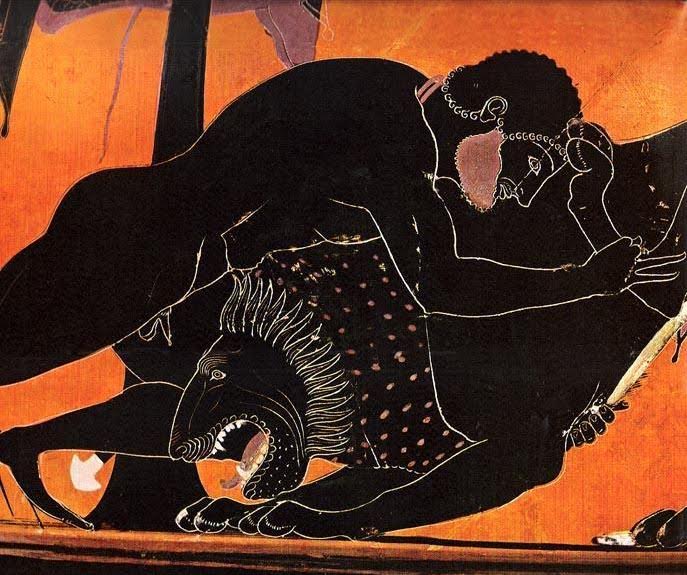

IV – The Erymanthian Boar

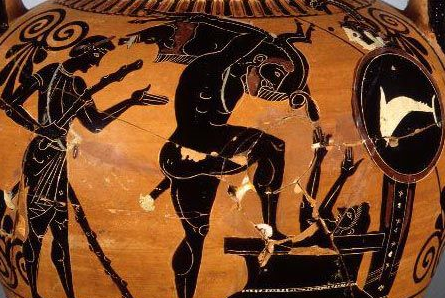

Herakles delivers the Erymanthian Boar to Eurystheus

Around Psophis, in the Arcadian region of the Peloponnese, a massive boar had been giving the locals trouble and so Herakles was sent to capture it. He did so by pursuing it through deep snow in the mountains until it was so exhausted that he was able to capture it. Such a massive specimen would have made quite a sacrificial feast!

V – The Stables of Augeas

Athena aiding Herakles to clean the Augean Stables

Augeas was the King of Elis, and he had a cattle stable that had never been mucked out, EVER! In this case, it was not a monster that terrorized the locals, but rather the monumental stench. In this very different labour, Herakles was told he had to clean out the stables. So, what did he do? What all heroes would do, he diverted the rivers Alpheius and Peneius so that they flowed through the stables and washed the titanic stink away. It’s no wonder the land thereabouts is so fertile!

VI – The Stymphalian Birds

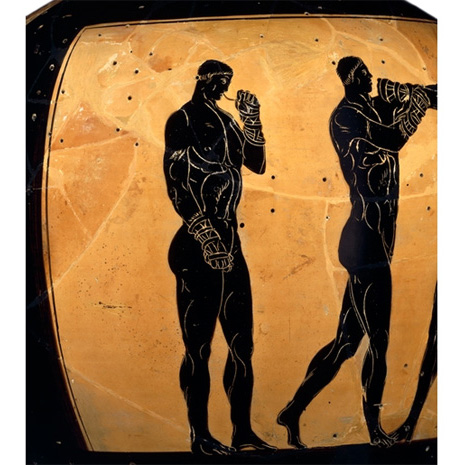

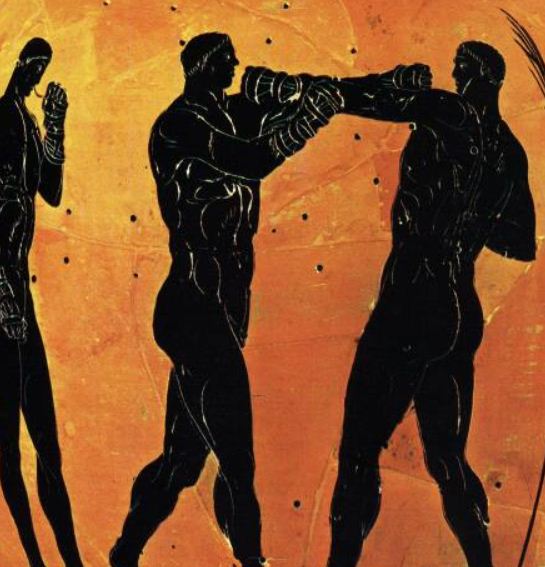

In Stymphalia, there were flocks of man-eating birds with bronze beaks that infested the woods around the Lake of Stymphalus, again in Arcadia. Herakles was told he had to get them out. So, he scared them all from their hiding places and then shot them down with his great bow. No more birds.

Lake Stymphalos

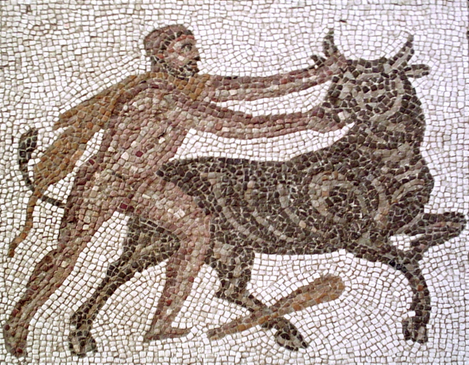

VII – The Cretan Bull

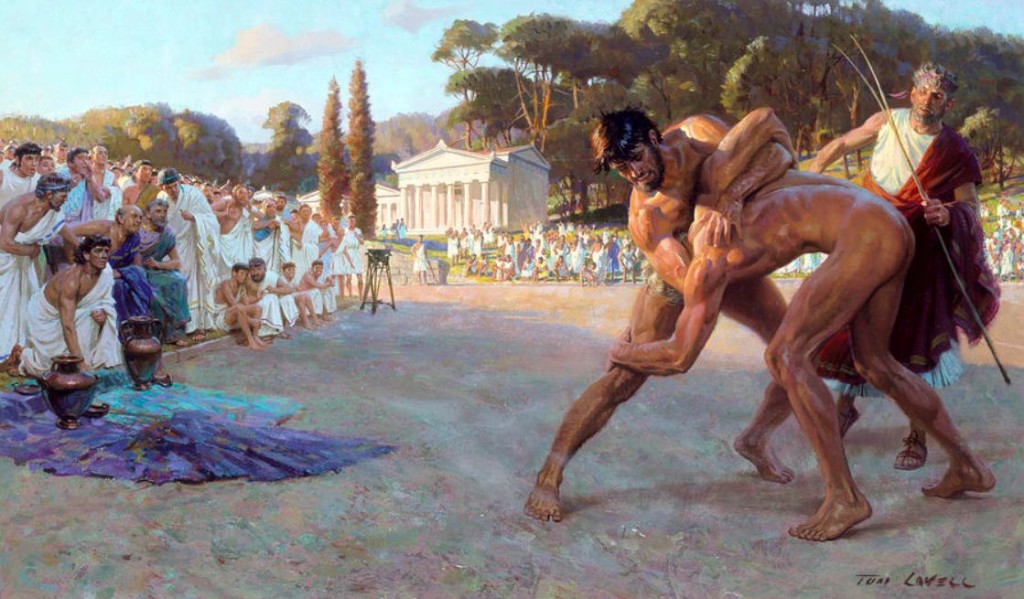

For his seventh labour, Herakles had to leave the Peloponnese for the Island of Crete to capture and bring back the Cretan Bull. This was no ordinary bull. This was the bull that Poseidon sent to Crete for King Minos to sacrifice. When Minos refused, Poseidon made his wife, Pasiphae fall in love with it and from that union was born the terror that was to become the Minotaur. The Cretan Bull rampaged all over Crete until Herakles arrived, wrestled it to the ground, and brought it back to Greece. The hero’s friend, Theseus, would come back to Crete years later to take care of the Minotaur.

The Cretan Bull

VIII – The Mares of Diomedes

Once more, Herakles was forced to deal with another group of man-eating animals. But this time they were not birds, but rather horses! The mares of Diomedes were in Thrace.

When Herakles arrived in that northern kingdom, he had a run-in with Diomedes himself and so, to tame the horses, Herakles fed them their own master. After that, the mares followed him back to Eurystheus.

The man-eating Mares of Diomedes

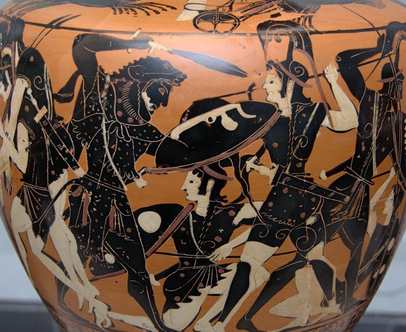

IX – The Girdle of Hippolyte

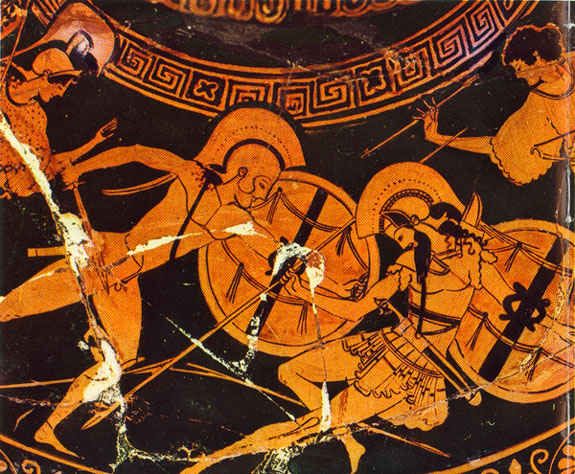

Herakles fighting the Amazons

Near the River Thermodon, just off the Black Sea, Herakles and his followers, including Theseus, went to the Amazons and their Queen, Hippolyte. The story goes that Herakles just asked this lovely daughter of Ares for her girdle, or belt, and she said ‘Yes’. Hera decided to step in and whispered to the rest of the Amazons that their queen was being abducted.

The Amazons attacked Herakles and his men who fought back, and in the bloody engagement, Hippolyte herself was killed. Herakles managed to get the girdle, but the cost of this labour was indeed heavy.

The River Thermodon

X – The Cattle of Geryon

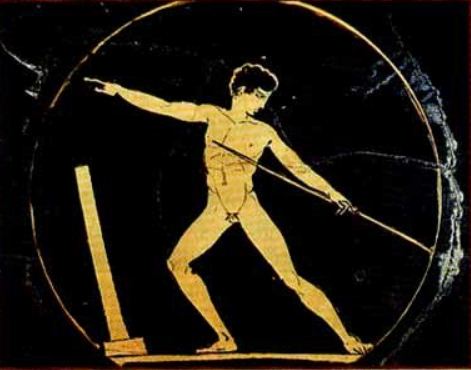

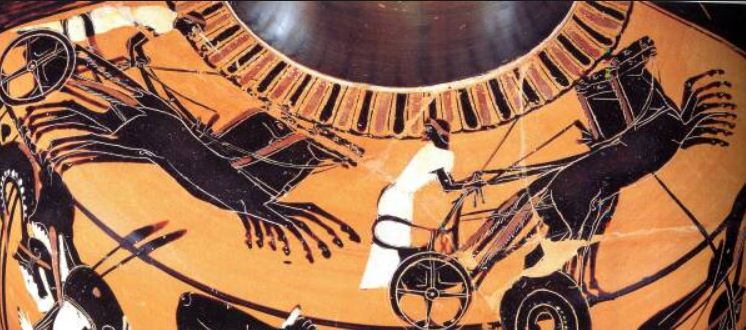

The tenth labour is a sort of epic cattle raid. Herakles was told he had to bring back the red cattle of the three-bodied giant, Geryon, from the Island of Erytheia which was far, far to the west. This took the hero on a long journey into the Atlantic. On his way, he set up the Pillars of Hercules to mark his way.

Herakles driving off the Cattle of Geryon

But Herakles began to grow weary with the heat, and so Helios, God of the Sun, lent Herakles his great golden bowl or boat so that he could sail the rest of the way to Erytheia. Herakles succeeded in raiding the cattle and sailed in Helios’ boat back to Spain. From Spain he travelled to Greece and had many adventures on this mythic cattle drive.

There is a whole list of adventures he had on his way home, but the one I would like to highlight brings him in touch with the Romans. When Herakles arrived in Rome he came into conflict with a monster named Cacus after the beast killed some of the cattle. Herakles killed Cacus in what must have been a great battle of strength.

Temple of Hercules, Rome (Wikimedia Commons)

It’s interesting that in Rome, there are some steps leading off of the Palatine Hill called the Steps of Cacus which is where the monster is said to have lain in wait for passers-by. In the Forum Boarium, or cattle market, near the banks of the Tiber, there is a round Tholos temple dedicated to Hercules, commemorating the hero’s time in Rome.

XI – The Golden Apples of Hesperides

Hesperia was the garden of the gods, and Herakles must have been exhausted when he discovered that he had to go back to the Atlantic. Some believe Hesperia was located on the Atlantic side of the North African coast. The garden was said to be beyond the sunset, where Atlas, the Titan, was holding up the sky.

The Golden Apples of Hesperides

The labour was to pick the golden apples that were guarded by a giant snake. In some stories, Herakles asks Atlas to pick the apples for him while he holds the heavens in his stead. In others, Herakles picks the apples himself and kills the serpent.

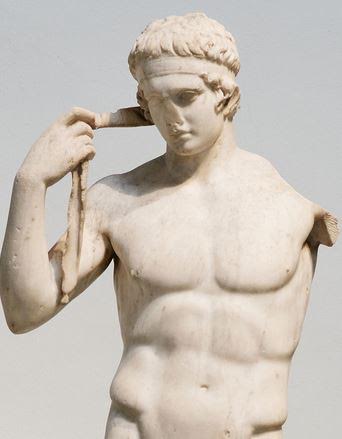

XII – Cerberus

There is one archetype that is common to most hero stories, and that is the journey to the Underworld. And this is where Herakles must go in his final labour, to bring the three-headed hound of Hades back to Eurystheus.

Herakles and Cerberus

To get to the Underworld, Herakles gets help from the god Hermes, who travelled there regularly. Supposedly, they entered through the gate at Taenarum, in the southern Peloponnese.

There is a fascinating episode when they arrive in Hades’ realm. The shades of the dead flee from Herakles who wounds Hades himself with one of his poison arrows. The only shades who do not flee are Meleager, famed for bringing down the great Calydonian Boar, and Medusa, the Gorgon slain by Perseus.

Gate to Hades at Taenarum

Herakles drew his sword against Medusa, but Hermes told him to leave her be. But Meleager told the hero his sad tale. Herakles, inspired by Meleager, said that he would marry the sister of such a noble man. And so, the shade of Meleager named his sister, Deianaira, to be Herakles’ wife. This at the end of his long penance for killing his family. Was it a new beginning?

Hades told Herakles that he could take Cerberus if he could bring him to heel without using his weapons. In true Heraclean fashion, he wrestled the hell hound and then brought it to Eurystheus.

Afterward, Hades got his dog back.

Herakles resting after his Labours