Serious sport has nothing to do with fair play. It is bound up with hatred, jealousy, boastfulness, disregard of all rules and sadistic pleasure in witnessing violence: in other words it is war minus the shooting.

(George Orwell, “The Sporting Spirit”, Tribune, 14 December 1945)

I was reminded of the above Orwell quote in a book I’ve been reading lately, entitled The Ancient Olympics, by Nigel Spivey. No, we are not going to be talking about modern warfare or guns, those are not my thing. However, Spivey’s use of the quote is apt for his book, and for the purposes of our short discussion here.

What was the purpose of athletic competition in the ancient world, and what is the purpose of it today? How has it evolved, or has it?

I’m just finishing up the research phase for my novel set during the ancient Olympics. I can’t wait to start typing away at it, but there are a few things I need to decide on, one of them being how I will portray the ancient games.

I’m a romantic, and an idealist, and at first my inclination is to portray the ancient Olympics in an idealized and romantic light. It would make for a great story, but would that be accurate?

Today, when we think of the Olympic Games, we think of amateur sport, sportsmanship and fair play. We believe that just to be able to compete in the Olympics is an honour, a victory already achieved. In some ways, that’s true. The athletes who go to the Olympics today have trained and competed for years. They’ve racked up a list of hard-won victories in their part of the world in order to make it to the Olympiad.

I love the Olympics. In fact, it’s the only time that I really watch sports on TV. I love the Olympic ideals we hold so dear.

But are those the same ideals that were held dear in the ancient world? Perhaps some. But not all. Are the Olympics today the same games that they were in the ancient world? No. Not really.

So, in writing my story set during the ancient Olympics, I’ve got to achieve a major shift in mindset and go somewhere my modern sensibilities will not necessarily enjoy.

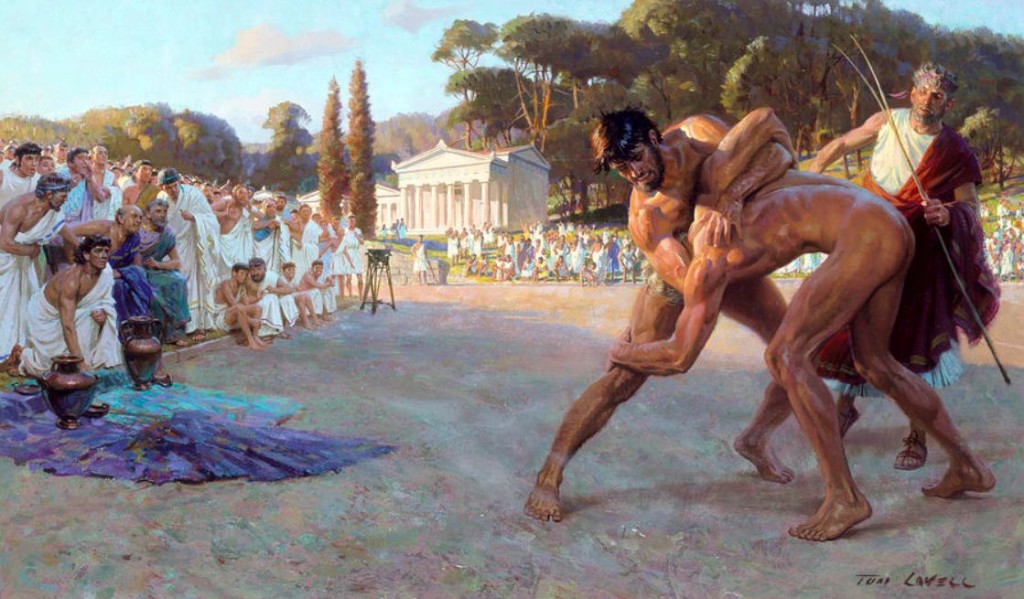

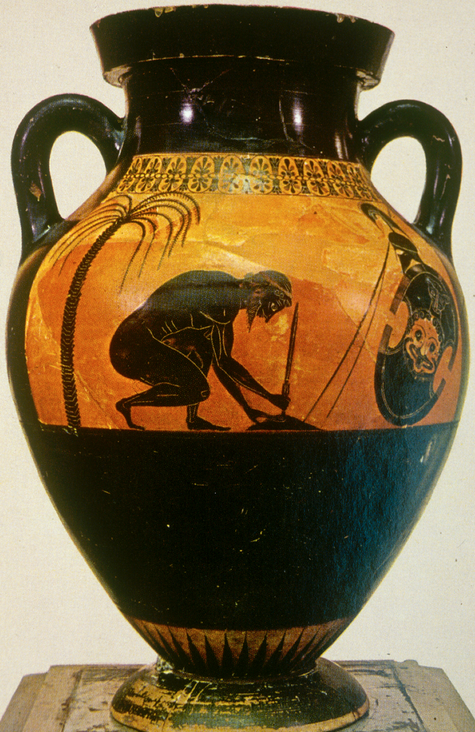

In the ancient world, men (yes, only men) went to the Olympics to win (women were only permitted to compete insofar as owning the horses in the equestrian events). It was not honourable to just participate. Oftentimes, losers would have to return to their polis by back streets, humiliated that they did not wear the olive crown of victory. Only the winners were hailed as demi-gods. The losers, though participants in the great games, were nothing.

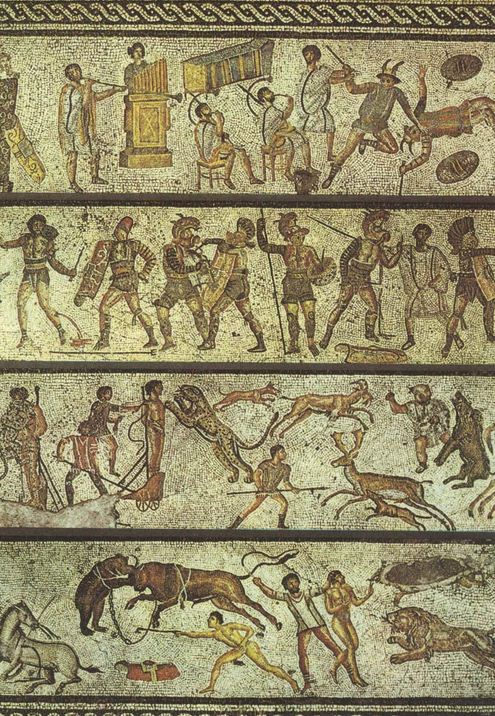

It’s pretty harsh, but that was the nature of the Olympics and other games (including the Isthmian, Pythian, and Nemean games). They were violently competitive, brutal in nature, and though the Olympics were a time of official peace (the ‘Sacred Truce’), they were anything but peaceful.

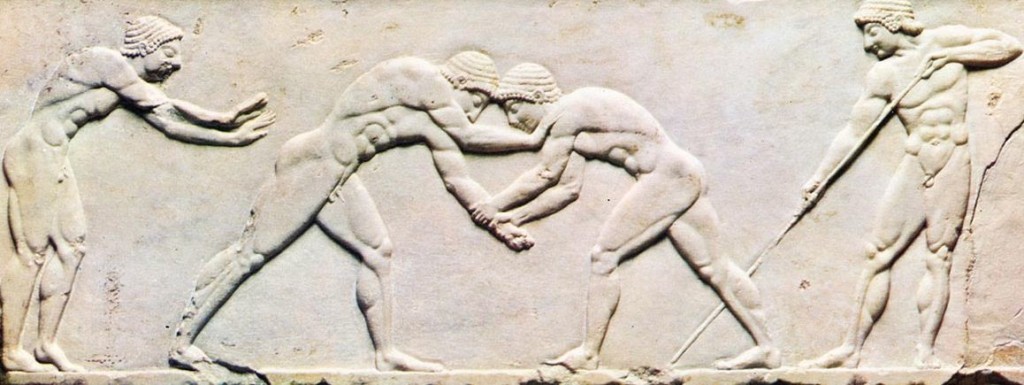

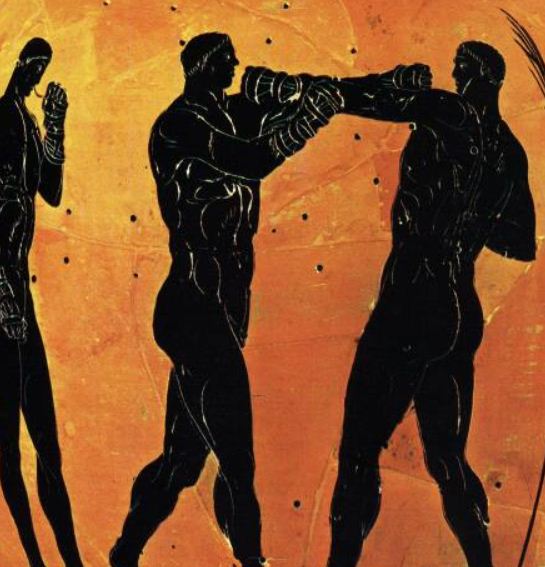

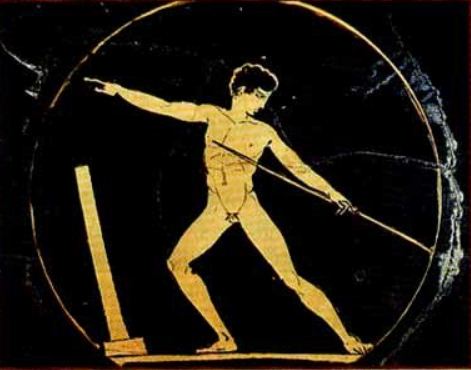

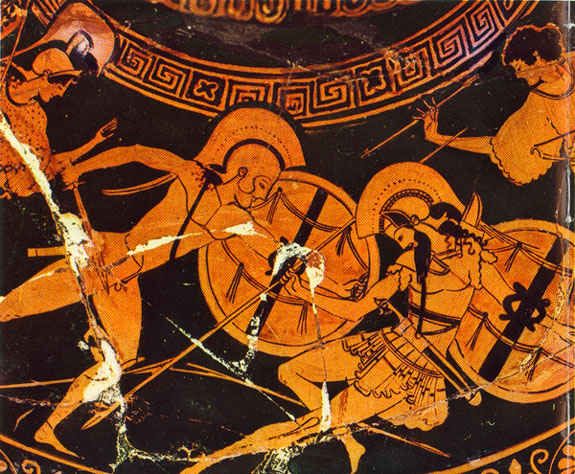

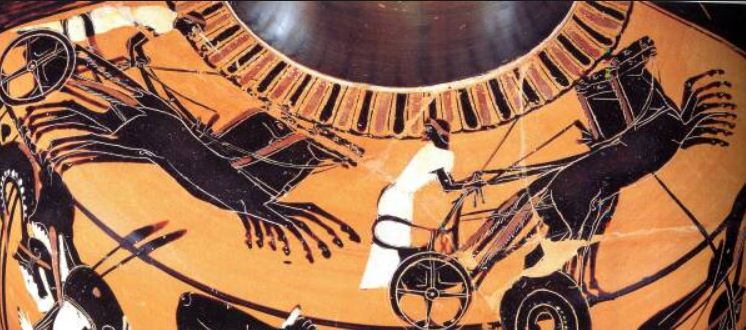

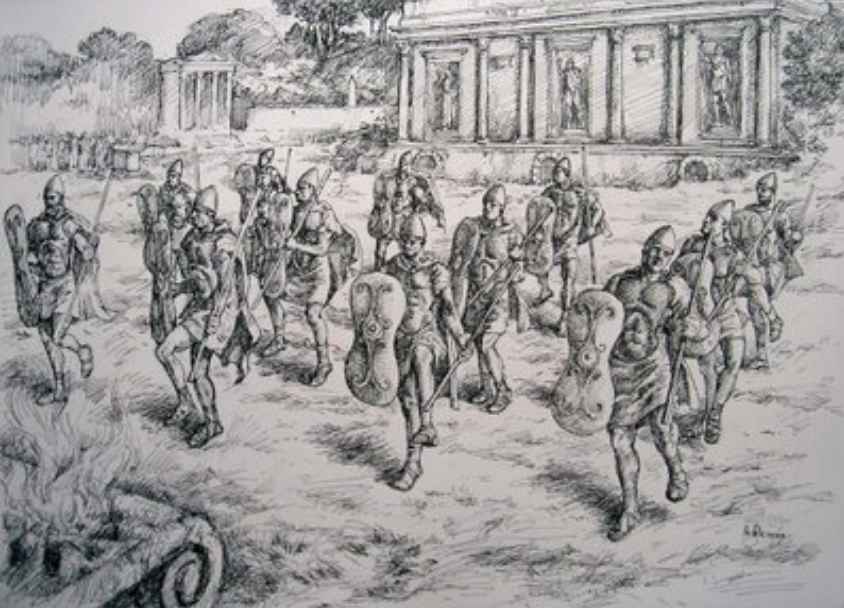

When I think of the ancient Olympics, I don’t think about gymnastics or synchronized swimming, kayaks, or graceful dives from on high. I think of boxing and the discus, hoplite warrior sprints and the roar of a crowd at the marquee chariot races. When I think of the ancient Olympics, I think of the pankration, that most brutal of events where bones were broken, and faces were smashed with fists covered in lead or leather.

So, were ancient sports just about a sadistic pleasure in violence, about merely bettering your competitors, about hatred being given a release? Was sport really war on a small scale?

There isn’t really a straight and easy answer to the question, I’m afraid. I suppose the answer is yes, and no. Certainly, when you look at the array of events, the games were in one form, a training ground for war, “war without the shooting”.

As today, there were probably ‘good’ and ‘bad’ men who competed. There were those whose sole purpose was to utterly humiliate and destroy their opponents, to inflict pain and suffering, but there were also men who, in competing in the sacred Olympiad, sought to honour not only their polis and their family, but also to honour the gods themselves.

That said, they all wanted to win. I suspect that athletes today, no matter how much the media proclaims their virtue for simply being there, today’s athletes, once there, can see that victory within their grasp, and so, crave it more than we realize.

There is a duality here that leads us to the nature of Strife in the ancient world, which Spivey touches on in his book.

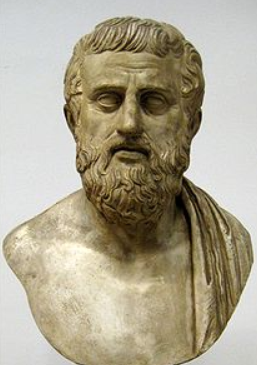

The ancient poet Hesiod (circa 700 B.C.) spoke of Strife in his Work and Days.

So, after all, there was not one kind of Strife alone, but all over the earth there are two. As for the one, a man would praise her when he came to understand her; but the other is blameworthy: and they are wholly different in nature. For one fosters evil war and battle, being cruel: her no man loves; but perforce, through the will of the deathless gods, men pay harsh Strife her honour due. But the other is the elder daughter of dark Night, and the son of Cronos who sits above and dwells in the aether, set her in the roots of the earth: and she is far kinder to men. She stirs up even the shiftless to toil; for a man grows eager to work when he considers his neighbour, a rich man who hastens to plough and plant and put his house in good order; and neighbour vies with is neighbour as he hurries after wealth. This Strife is wholesome for men. And potter is angry with potter, and craftsman with craftsman, and beggar is jealous of beggar, and minstrel of minstrel. (Hesiod, Works and Days)

Here we see that ‘Strife’, who is named Eris, actually has two faces, or natures.

There is Strife as Eris agathos, the useful, productive aspect of Strife, that which lends itself to creative industry in all things, in people of all stations and trades.

Then there is the Strife known as kakochartos, or ‘exalting in bad things’. This aspect of Strife thrives on war and dissent, a lust for bloodshed and battle.

Both aspects of Strife were present in the ancient Olympics and other competitions, both were present in war.

In his Theogeny, Hesiod names three offspring of Strife. They are: Death, Destruction, and Toil (Ponos).

It is ‘Toil’ that the ancients ascribed goodness to, for in working to the extremes of ones capabilities, and beyond, one became stronger, and so achieved greatness. This sort of Strife, Eris agathos, was pleasing to the gods, it was something to aspire to.

But the two aspects of Strife are not, in my opinion, mutually exclusive.

Spivey mentions the Iliad, and the part of that wondrous foundational text of western literature where Achilles embodies both aspects of Strife. Homer does not differentiate.

Therefore, perish strife both from among gods and men, and anger, wherein even a righteous man will harden his heart- which rises up in the soul of a man like smoke, and the taste thereof is sweeter than drops of honey. Even so has Agamemnon angered me. And yet- so be it, for it is over; I will force my soul into subjection as I needs must; I will go; I will pursue Hector who has slain him whom I loved so dearly, and will then abide my doom when it may please Jove and the other gods to send it. (Home, Iliad 18)

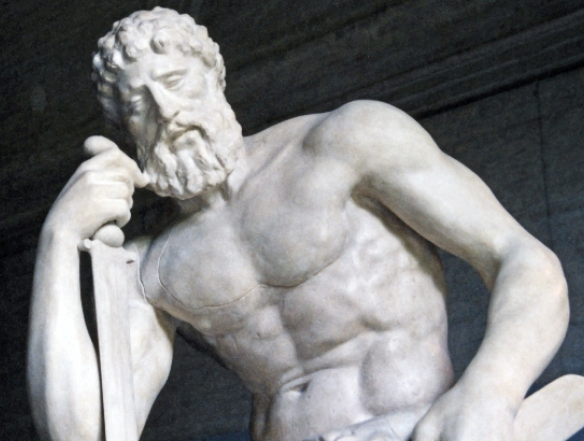

Achilles is by far the greatest hero of the Trojan War, the most skilled. He is godlike. He is what all men aspired to be. He is skilled at war, but can be unbelievably violent in the extreme, such as when he drags Hector’s body behind his chariot. He can, however, be moved to goodness such as when he sets aside his vendetta with Agamemnon to help his brothers again, and when he grants King Priam the return of his son’s body for the rites.

Greatness is not an easy thing to carry upon one’s shoulders, and we see in ancient literature that the heroes who achieve greatness also have a greater measure of grief. Herakles, Jason, Achilles and so many others all have tragedy in their lives, but Eris agathos was with them too, and this set them apart from the base war-mongers of the age, those who throve on kakochartos.

Olympians would have been weaned on tales of these heroes, and many would have aimed for such heights. One of the most famous of Olympians was Milo of Croton who won numerous wrestling victories at all of the Pan-Hellenic competitions for many years.

This same Olympic hero was also a great warrior who led troops of his native Croton in battle against their enemies of Sybaris.

One hundred thousand men of Croton were stationed with three hundred thousand Sybarite troops ranged against them. Milo the athlete led them and through his tremendous physical strength first turned the troops lined up against him. (Diodorus Siculus XII, 9)

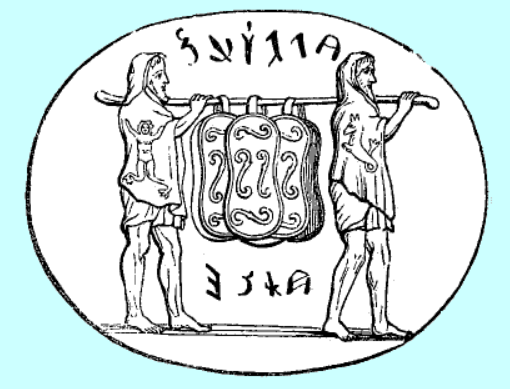

It is said that Milo led the charge against the Sybarites wearing his Olympic crowns, a lion skin, and wielding a club similar to the hero Herakles. It seems that war and athletics were both at their finest in Milo, and I suspect that it was so in many an ancient Olympic champion.

Herakles wearing a victor’s wreath – This is how Milo supposedly dressed for the battle with Croton’s enemies