As many of you will know, I recently returned from a weeklong vacation in Devon and Somerset. This was a combined family adventure and research trip for some upcoming books.

Needless to say, I had a wonderful time and have returned to the big city relaxed, inspired, and ready to hunker down and write the next book. I also want to share some of my lovely experiences with you, to introduce you to some of the places that came alive for me.

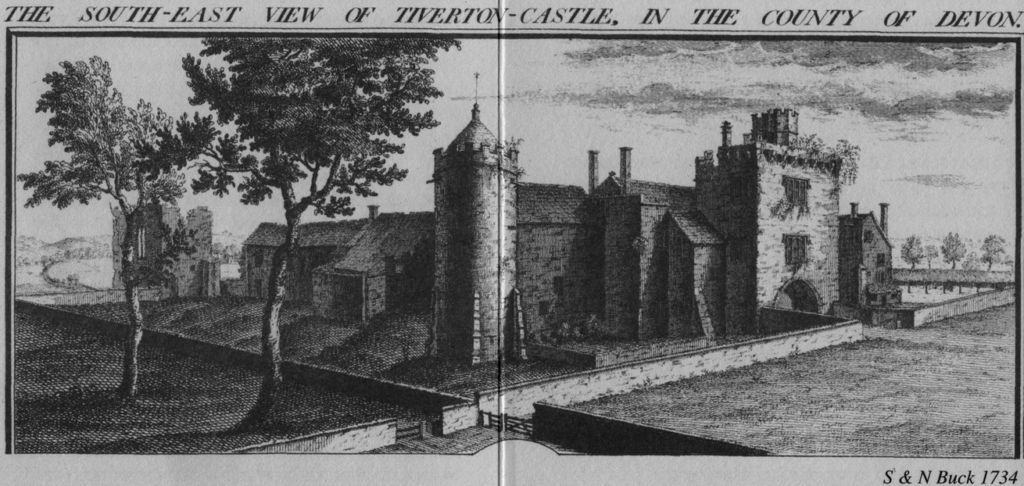

The first destination was Tiverton Castle in Tiverton, Devon.

This castle holds a special place in my heart, but before two weeks ago I had not been back for 15 years.

For a long time, I’ve been daydreaming about a return visit to this lovely castle tucked away in Devon, between Exmoor and Dartmoor.

When our car pulled up, it was like being welcomed by an old friend after too long an absence.

Before I talk about my experience revisiting this castle, we should discuss the history of this place. After all, that’s what this blog is all about!

Tiverton Castle may not be one of the titans of tourism in Britain, but it is no less deserving of a visit, and if you are up for it, a stay within its walls.

There has been human habitation around Tiverton since the Stone Age, but the town itself really peaked financially with its thriving wool trade in the 16th and 17th centuries.

However, I want to focus on the castle itself, for it has a long and varied history that is both fascinating and tragic.

Prior to the Norman Conquest of 1066, the land upon which Tiverton castle would later be built formed part of the estates of the Saxon Princess, Gytha, the sister-in-law of King Canute, and the Mother of King Harold. After the Conquest, the lands came into the possession of William the Conqueror (King William I) and his heirs.

In 1100, when Henry I came to the throne, he began granting land to some of his followers for the purpose of building castles. It was at Tiverton that Henry I commanded Richard de Redvers to build a castle overlooking the important crossing point of the River Exe. This early fortress was probably completed around 1106.

Richard de Redvers’ son, Baldwin, became the 1st Earl of Devon and the manor of Tiverton continued to be held by six successive earls until 1262 when the male line died out. The last earl was succeeded by his sister Isabella, a widow, who assumed the title of Countess of Devon and was one of the richest heiresses in the land. When Isabella died, Tiverton went to her cousin, Hugh de Courtenay.

The Courtenays are thought to be largely responsible for the bulk of the building at Tiverton Castle, the medieval remains of what we see today.

It’s believed that the family originally came to England in the entourage of Eleanor of Aquitaine.

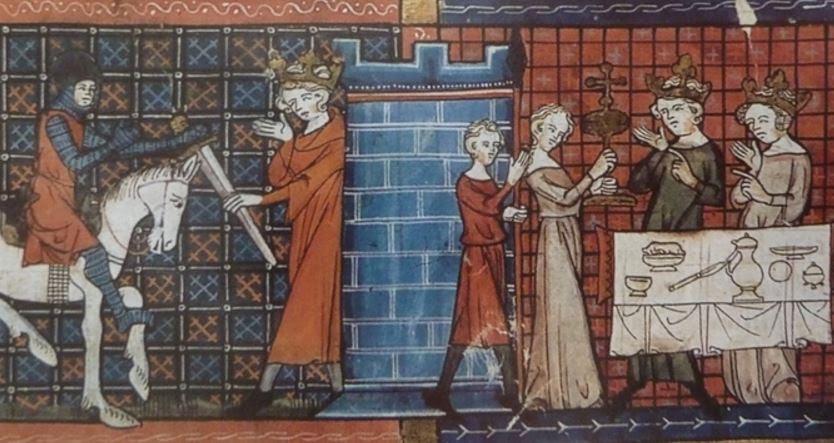

In 1335, it was King Edward III who made Hugh de Courtenay Earl of Devon at Tiverton Castle, and it is believed that Hugh was responsible for building the curtain walls with towers at the corners, and the living quarters on the west side by the river.

The Courtenays held Tiverton Castle for about 260 years until, during the Wars of the Roses, the castle and title were lost to the family as some of them were staunch Lancastrian supporters.

With the death of Richard III at the Battle of Bosworth in 1485, however, it was Henry VII who reinstated Sir Edward Courtenay as Earl of Devon at Tiverton Castle. In about 1485, his son, William Courtenay married Princess Katherine Plantagenet, the daughter of Edward IV, and sister of Henry VII’s queen, Elizabeth.

Katherine had something of a sad life – she was also the sister of Edward V of England and Richard of Shrewsbury, Duke of York, both of whom are rumoured to have been killed in the Tower of London by their uncle, Richard III. If you’ve read Shakespeare’s play, you’ll know all about this.

The daughters of King Edward IV and Elizabeth Woodville with Princess Catherine Plantagenet second from the right

Princess Katherine was the most famous resident of Tiverton Castle. She lived there for many years, after outliving her own children, and when she died in 1527, she was buried (at her request) in St. Peter’s Church next door.

Princess Catherine’s tomb is believed to lie beneath the tomb of this merchant in St. Peter’s Church. The very bottom is said to be part of her burial.

During the years of the English Civil War, more building was done at Tiverton Castle, which was held for King Charles I.

It was widely acknowledged that Tiverton held great strategic importance at this time, and so this led to the only occasion in which the castle faced an enemy attack. The Parliamentary army, under the command of Sir Thomas Fairfax, commenced bombarding the castle with cannon and gun.

It was a lucky cannon shot that hit the drawbridge chain, allowing the Parliamentarians to rush into the castle and church to plunder. Few lives were lost in the siege, but for one woman who was hit by a cannon ball in the round tower while holding her child. The child survived.

I’ve glossed over the rich history of Tiverton Castle, opting to give you some of the highlights. There is much more to it, but I feel that a visit to the castle itself is the only way to do it justice.

After the Civil War siege, Tiverton Castle was under the ownership of various families over time. Today, it is owned and lovingly cared for by Angus and Alison Gordon who give a warm welcome to any visitors to the castle.

Over time, the Gordons have become family friends, and Tiverton Castle a place that we will return to when we are in need of an escape.

The Castle Lodge, our wonderful self-catering accommodation at Tiverton Castle. This is just one of many beautiful accommodations!