Readers and History-lovers!

Welcome back to The World of An Altar of Indignities, the blog series in which we share the research for our latest novel, An Altar of Indignities: A Dramatic and Romantic Comedy of Ancient Rome and Athens.

If you missed the third post on Roman monuments of Athens, you can read that by CLICKING HERE.

In part four of this blog series, we’re going to be looking at food and dining practices in the Roman world because, let’s face it, food is a big part of culture, past and present!

Let’s get started.

Recreation of Roman foods

In the Roman Empire, diet, and the food that made up that diet, changed according to geographic region and the economic situation of the folk you are talking about. It wasn’t like today where we can just head down the street and buy a pineapple at any time of year. As a rule, there was no mass, global transportation of foods. Romans ate local for the most part, unless you were talking about wine, olive oil, olives and specialty items like garum. We’ll talk about those later.

First off, we need to dismiss the perception that Romans always ate elaborate meals with trays of songbirds, dormice, buckets of wine, and mountains of exotic fruits. This was not a usual occurrence, and when it did happen, it was usually the super-rich or the imperial family who ate like that, and then, only once in a while.

The truth is that the Roman diet was rather simple and, dare we say it, probably pretty healthy. Think Mediterranean diet.

Generally, the staples were various grains, often used in a sort of porridge known as puls, and breads made from a species of wheat known as frumentum. There was no such thing as pasta in ancient Rome! Panem et puls were the go-tos! Beans and lentils were also staples, and research has shown that these, rather than meat, were the breakfast of champions for gladiators!

To hear more about various types of grains from Pliny the Elder, CLICK HERE.

Fruits such as figs, grapes, and olives (yes, olives are technically, a fruit!) were eaten when available, as were a large variety of vegetables that made up the Roman diet. They did not have tomatoes or potatoes in ancient Rome, but they did eat a lot of cabbage, onions, garlic, parsnips, marrows, radishes, lettuce (not Caesar salad BTW!), asparagus, beets, and celery.

Mosaic depicting asparagus

When it came to meats, these were usually consumed as part of the main meal of the day, however that was not as likely or often for the poor. Sausages and domestic fowl were relatively common, as was pork, the latter being a special feature of certain festivals such as Saturnalia. Oysters and fish were very popular in ancient Rome, but there was the constant challenge of keeping them fresh when being delivered from the seaside to the city. It has been suggested that these were transported live, in barrels, to the places where they were to be consumed.

Needless to say, food poisoning may have been a common occurrence in ancient Rome, especially if one had a taste for oyster and other shell fish.

But let’s not think that there was nothing exotic on the Roman dining table. Well-to-do Romans would have consumed game such as venison or wild boar, snails and dormice (yes, little mice!) that were especially bred for the purpose of consumption, as well as small, wild birds or songbirds. If one attended a really fancy convivium, or banquet, one might even have had the chance to eat some peacock or swan.

Mosaic depicting typical Roman foods

With all of the foods mentioned above, I would be remiss if I did not make mention of the wide variety of fresh herbs and spices (too many to name here!) that Romans put on their food.

Romans liked their food highly spiced and cooked in sauces. Garum, a fermented fish sauce, was among the most popular. You can read more about garum by CLICKING HERE.

And there were desserts too! But these were not sweetened with sugar as we know it, but rather with honey. Romans, when they did have sweets, had a variety of cakes, pastries and tarts all sweetened with sticky goodness from the hive.

Lastly, what Roman shopping list would be complete without the two greatest liquid staples in the Empire? I am, of course, talking about wine and olive oil. These were both common in any household and came in varying qualities, depending on one’s income.

Amphorae that would have been used to transport and store wine and olive oil.

So how and where were all of these foods prepared?

Once again, this depended on the means of the household. Some kitchens were bigger than others, the same as today. In the case of tenement apartments in the Suburra, for instance, they did not have kitchens or cooking spaces which would have taken up much-needed space and been a severe fire-risk in the building.

In the case of tenement dwellers without kitchens of their own, there were communal ovens that were used, as well as plenty of food stalls where meals could be purchased – ancient Rome’s answer to take-out curry!

For those homes that did have kitchens (indoor or outdoor) the space often consisted of a round, or domed oven where a cook-fire was kindled with wood or charcoal. Cauldrons were also suspended over fires, as were frying pans or skillets.

Roman pans and skillets for cooking

When meat was cooked, it was more often boiled with a sauce, rather than roasted or grilled, although skewered roast meats were available, likely sold street-side.

I tell you, souvlaki has been around a long time!

Preservation of food was also important in ancient Rome, and so the curing and smoking of meats was common, as was the use of salt and pickling in vinegar for preservation.

What some archaeologists believe to be a sort of ancient souvlaki rack

Now we come to it, however, the nectar of the gods – wine!

Eight glasses of water a day?

Not in ancient Rome.

The most common drink in ancient Rome was wine. It was usually watered down, as it was considered barbaric to drink it undiluted, which is a shame if you ask me. But watered wine is not so bad. Go on, give it a try!

Just as with olive oil and garum, there were varying qualities of wines made at home and outside of the Italian peninsula.

Wine and bread? Yes please!

In addition to the fine Falernian and Chian vintages that might have graced the tables of the wealthy, there was also a wine concentrate that had to be diluted in water.

Among the poor, the drink of choice was posca, a sort of watered down acetum akin to wine vinegar. It might have had a bite, but perhaps it helped to keep one’s innards clean?

We prefer medieval Chianti Classico.

In Rome, beer and mead were not widely available and were much more common in the northern provinces.

And milk? Not so much. It was considered uncivilized to drink, the preferred use of dairy being to make cheeses, which were central to the Roman diet.

Fresco of a Roman dining scene

Now we’re going to take a brief look at the eating habits and formalities of dining in ancient Rome.

When it comes to eating, we seem to have inherited some of our modern-day habits from the Romans.

They normally ate one large, main meal a day, along with two smaller ones. However, the ientaculum, that is, breakfast, to the Romans, was not the most important meal of the day as we are sometimes told. In fact, Romans might have skipped this altogether before heading down to the Forum or visiting with clients or benefactors.

Breakfast in ancient Rome was light, and most likely involved puls, a sort of porridge, or some bread, perhaps dipped in honey or olive oil. They didn’t attack the day with a lumberjack breakfast in their stomachs!

In the early days, the midday meal or lunch, known as the cena, was the main, large meal of the day. This would perhaps have coincided with the sexta, the sixth hour of daylight, or siesta time of day. For more about the Roman siesta, CLICK HERE.

Lastly, the Romans would have enjoyed a lighter evening meal called the vesperna, perhaps involving bread and cheese, or some fruit.

Sensible eating for those early Romans!

Over time, however, the midday lunch became a lighter meal known as the prandium, and the cena, the main meal, was moved to the evening.

For the poor, most meals would have consisted of puls or bread, sometimes with some sort of meat, or vegetables if they were available. There was certainly less variety among the different meals of the day if one was not wealthy or at least well-off.

For the rich and well-to-do, things were different. As the cena was the large meal of the day it would have included three courses of food.

The first course was the gustatio or promulsis, and this would have involved appetizers of olives, eggs, raw vegetables, and simple fish or shell fish.

The second, or main course, the prima mensa, often included cooked vegetables and meats, the types and amounts varying greatly, depending on the occasion and wealth of the family or individual.

And lastly came the sweet course, the secunda mensa. This is when fruit and sweet pastries would have been served.

Fresco of eggs, wine, and songbirds. The makings of a cena, perhaps?

But what about the etiquette of dining? What was the etiquette? How did they sit? Did the Romans just move from course to course, gobbling up all that was placed before them?

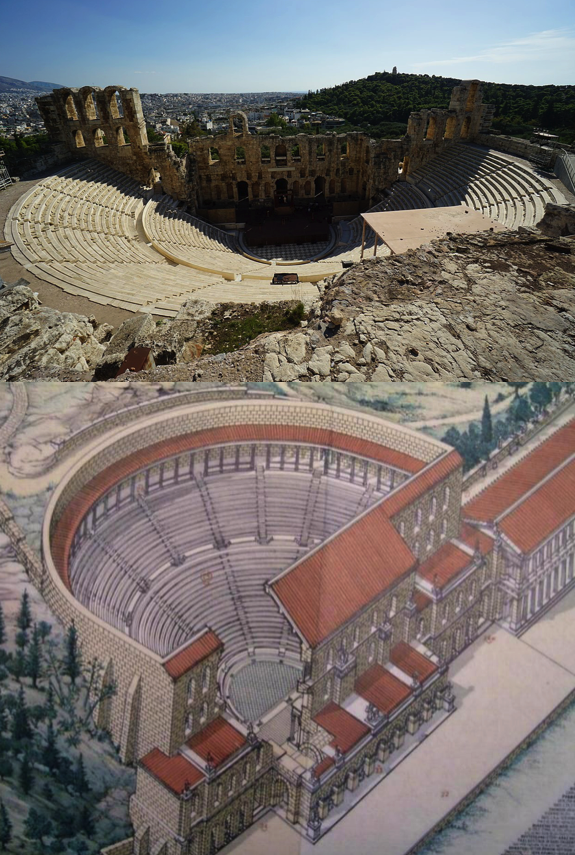

Not exactly. In fact, there was a rigid system of seating, or placement. Contrary to modern views, most Romans ate while sitting, but when it came to the wealthy, they tended to recline on couches, especially at dinner parties.

At a banquet, or convivium, there would also have been entertainment between courses, perhaps by clowns, dancers, or readings by poets.

Food was eaten with fingers, and cut with knives. Spoons were also used, but forks were not.

Hypothetical triclinium visualisation (created by Martin Blazeby)

Today, when one attends a dinner, there are sometimes places assigned to guests. There might even be name cards, and some hosts might distance themselves from their least favourite guests at the table.

Well, this was also true in ancient Rome!

Imagine you’re invited to an evening cena at a senator’s home. You’re greeted in the atrium and led through the house to the dining room, the triclinium, just off of the peristyle garden. It’s dark out, and the scent of lemon blossoms and jasmine are on the night air. After a cup of watered wine, you’re shown into the triclinium by one of the well-dressed slaves who shows you to the couch known as the lectus medius, the middle couch of three, the couch of honour.

At this point, you’re very happy, for your host, seated with his wife on the lectus imus, the low couch, has honoured you above all other guests. The other guests behind you grin and bear it as they are shown to the high couch. From where you are, you have a wondrous view of the night garden and all of the other guests, and conversation comes easily, for you do not have to twist and turn.

Sound like a good evening? It could be. But the Romans took seating of this sort very seriously.

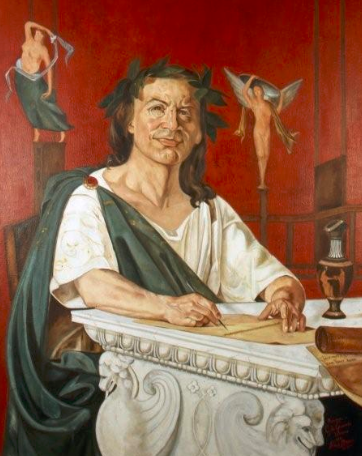

Horace (65 B.C. – 8 B.C.), in Satire VIII presents us with a scene depicting the seating arrangements and the trials of being a host in ancient Rome:

‘I was there at the head, and next to me Viscus

From Thurii, and below him Varius if I

Remember correctly: then Servilius Balatro

And Vibidius, Maecenas’ shadows, whom he brought

With him. Above our host was Nomentanus, below

Porcius, that jester, gulping whole cakes at a time:

Nomentanus was by to point out with his finger

Anything that escaped our attention: since the rest

Of the crew, that’s us I mean, were eating oysters,

Fish and fowl, hiding far different flavours than usual:

Soon obvious for instance when he offered me

Fillets of plaice and turbot cooked in ways new to me.

Then he taught me that sweet apples were red when picked

By the light of a waning moon. What difference that makes

You’d be better asking him. Then Vibidius said

To Balatro: “We’ll die unavenged if we don’t drink him

Bankrupt”, and called for larger glasses. Then the host’s face

Went white, fearing nothing so much as hard drinkers,

Who abuse each other too freely, while fiery wines

Dull the palate’s sensitivity. Vibidius

And Balatro were tipping whole jugs full of wine

Into goblets from Allifae, the rest followed suit,

Only the guests on the lowest couch sparing the drink.’

Horace (by Giacomo Di Chirico) Is he writing about the banquet he attended the night before?

Seems like Horace had a lot of fun with this, and his satires are certainly good for a laugh! We do feel for that host.

But what was all this ‘status seating’ about?

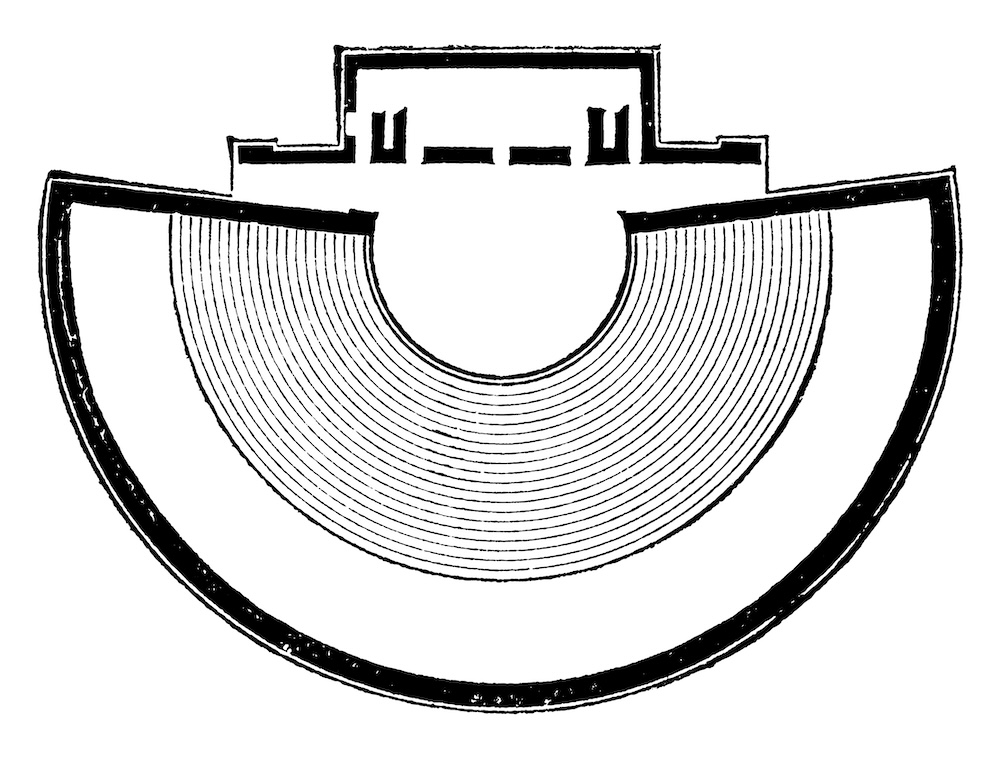

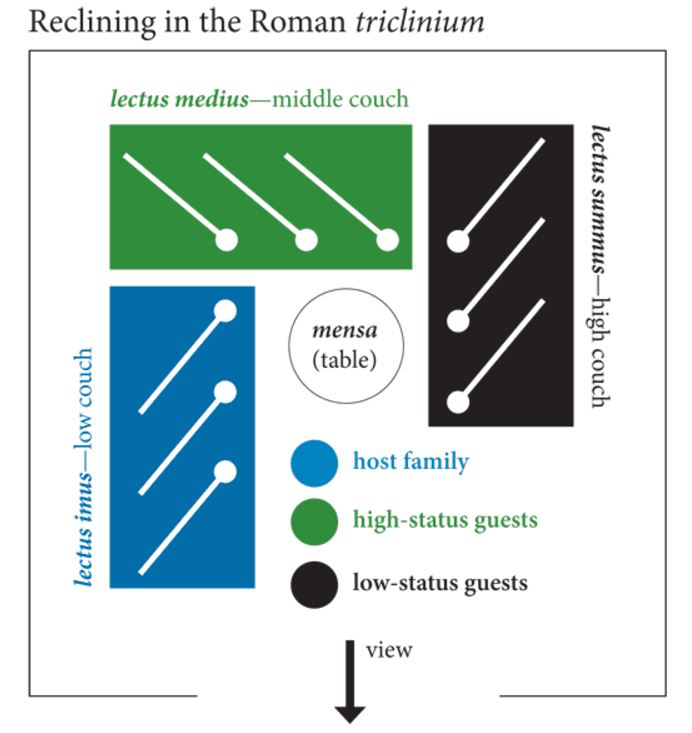

In a relatively well-off Roman household, three couches in a triclinium were standard. These were arranged around a low table, or mensa, and these couches had specific names and purposes.

The lectus medius, the middle couch, was the couch of honour, and was where important guests were placed. Because of its position, guests seated here were able to talk easily with other guests and had the best view, whether onto a peristyle garden or some sort of rural landscape.

The lectus imus, the low couch, was reserved for the hosts. It allowed them to speak with the high status guests on the lectus medius, and also the guests sitting directly across on the lectus summus.

Last and least, the lectus summus, or the high couch. This was not like the high table at a wedding today. No. The lectus summus in ancient Rome was the opposite. It was reserved for the lower status guests, maybe even for children if they were permitted to attend. This couch possessed less of a view, though still allowed its occupants the chance to participate in the conversation, though they might have had to turn awkwardly to do so. If you were shown to the lectus summus, then it seems you knew your place at the gathering.

If it was a rather large banquet, we can assume that the farther from the hosts and guest of honour you were on lectus summus side of the triclinium, the less important you were considered, or at least less influential.

Plan of typical Roman couch placement in a triclinium (from Reclining and Dining (and Drinking) in Ancient Rome by Shelby Brown; The Iris – Behind the Scenes at the Getty)

We hope you’ve enjoyed this article on food and dining in Roman society.

In researching this topic for An Altar of Indignities, and for other books such as Saturnalia: A Tale of Wickedness and Redemption in Ancient Rome, and Isle of the Blessed, we found that some of our modern perceptions about Roman banquets are indeed true, while others are clearly not. If one was eating in a tenement in the Suburra, you were not reclining on a couch eating grapes and drinking wine. It was a table and chair for you.

The food consumed, as well as the eating and dining habits of the poor and the rich were often separated by a wide gulf. Nevertheless, the wonderful colour and variety of the world of ancient Rome never ceases to delight!

Thank you for reading.

What a Roman market might have looked like.

There are more posts coming in The World of An Altar or Indignities, so make sure that you are subscribed to the Eagles and Dragons Publishing Newsletter so that you don’t miss any of them. When you subscribe you get the first prequel book in our #1 best-selling Eagles and Dragons series for FREE!

If you haven’t yet read any books in The Etrurian Players series, we highly recommend you begin with the multi award-winning first book Sincerity is a Goddess: A Dramatic and Romantic Comedy of Ancient Rome.

In celebration of drama in the ancient world, be sure to check out our ‘Ancient Theatre’ Collection in the Eagles and Dragons Publishing AGORA on Etsy which features a range of ancient theatre-themed clothing, glassware and more! CLICK HERE to browse.

An Altar of Indignities: A Dramatic and Romantic Comedy of Ancient Rome and Athens is now available in ebook, paperback and deluxe hardcover editions from all major online retailers, independent bookstores, brick and mortar chains, and your local public library.

CLICK HERE to buy a copy or get ISBN# information for the edition of your choice.

Brace yourselves! The Etrurian Players are back!