Greetings Readers and History-Lovers!

Welcome back to The World of An Altar of Indignities, the blog series in which we take a look at some of the research that went into our latest novel set in Ancient Rome and Athens.

If you missed Part VII on Herodes Atticus, you can read that by CLICKING HERE.

In Part VIII, we’re going to be exploring the great event that is at the heart of An Altar of Indignities: the Panathenaic Festival of Ancient Athens.

Not only does this ancient festival provide the backdrop for all of the chaos that ensues in the book, but it is the very reason The Etrurian Players find themselves in the city of the Goddess Athena in the first place.

We hope you enjoy…

Painting of ‘Golden Age’ Athens by Leo von Klenze (1846)

The Panathenaic Festival, or the ‘Panathenaea’, was a religious festival held at Athens in honour of the city’s patron goddess, Athena. It took place from about the twenty-third to the thirtieth day of the Attic month of Hekatombaion, which was mid-July to mid-August. It promoted unity among all Athenians, and eventually among all Greeks.

The Panathenaea was the most important religious festival of ancient Athens. There were annual and quadrennial celebrations of the festival in the form of the ‘Lesser’ and ‘Greater’ Panathenaea.

The ‘Lesser’ Panathenaea was held every year and appears to have been a slimmed-down version of the larger festival, though still a time of great import on the Attic calendar.

The ‘Greater’ Panathenaea – that which takes place in An Altar of Indignities – was held every four years, and included an array of religious ceremonies, athletic competitions, cultural events, poetry and music competitions, and of course the great Panathenaic Procession immortalized on the Parthenon Frieze (the ’Parthenon Marbles’), sculpted under the direction of Phidias.

Recreation of the west pediment statue group of the Parthenon showing the competition for Athens between Athena and Poseidon (Acropolis Museum)

And they that held Athens, the well-built citadel, the land of great-hearted Erechtheus, whom of old Athena, daughter of Zeus, fostered, when the earth, the giver of grain, had borne him; and she made him to dwell in Athens, in her own rich sanctuary, and there the youths of the Athenians, as the years roll on in their courses, seek to win favour with sacrifices of bulls and rams…

(Homer, Iliad, Book II, 549-550)

Before we get into the timeline of events that made up the Greater Panathenaea, let’s discuss what we know about the origins of the festival.

In mythology, it is supposed that the Panathenaea was founded by Erechtheus (continued by his son, Erichthonius), King of Athens, seven hundred and twenty-nine years before the first Olympiad which was held in 776 B.C.E. This first festival may have been called the ‘Athenaea’.

Later, after the sunoikismos under King Theseus of Athens, the amalgamation of the villages of Attica, it became known as the ‘Panathenaea’.

Historically, the Athenian ‘tyrant’, Peisistratos, and the ‘archon’ of the period, Hippoclides, are credited with the reorganization of the Panathenaic Games in 566 B.C.E.

The festival grew to symbolize Athenian unity and cultural excellence. It also became a stage for Athens to assert its influence within the Greek world, as foreign dignitaries and representatives from allied states participated in the festivities. The Panathenaea evolved into a multifaceted event blending religious devotion, athletic competition, musical performance, and civic pride.

It is believed the Panathenaea were held until about 410 C.E.

Statue of Athena – Full-sized recreation in the Nashville Parthenon

The Panathenaea was something of a beacon for the Greek world, just as the Goddess Athena was.

For Athenians, the Panathenaea was more than a religious celebration; it was a manifestation of their identity. The festival underscored their devotion to Athena, the goddess who safeguarded their city, and reinforced communal bonds through shared rituals and competitions. It was an occasion for political expression, with the display of Athens’ military and cultural supremacy.

The festival also offered a platform for social stratification. While the elite funded and organized events, the entire populace participated in the procession, showcasing Athenian democracy in action. Moreover, the Panathenaea fostered a sense of pan-Hellenic unity, attracting participants and spectators from across the Greek world.

Phidias Showing the Frieze of the Parthenon to his Friends (1868) by Sir Lawrence Alma-Tadema

The Panathenaic Festival, and especially the Greater Panathenaea, was an enormous and costly undertaking. During the Classical period, Greeks from around the Mediterranean would come to honour the Goddess Athena and to compete in everything from athletic and equestrian events to music and poetry competitions.

And it wasn’t just men who competed. There were also categories for boys, with divisions for paides (12-15 years), ageneioi (16-20 years), and andres (men over 20).

From inscriptions on artifacts, we know that there were prizes for winners, second place runners-up, and even others down the line, depending on the event. For musical contests, for example, a golden crown and money (valued around 1500 drachmae) was given to the winner, but also up to sixty amphorae filled with valuable Attic olive oil in red and black ware Panathenaic vases. Second place winners could receive a smaller sum of money, plus six amphorae of oil.

Some events were more richly-rewarded too. For example, the winner in the chariot race received money and one hundred and forty Panathenaic amphorae of olive oil! Another inscription indicates that a winner in the athletic races, however, could receive 1450 amphorae of olive oil and 2700 drachmae!

These amounts would likely have varied over time, but it is clear that victors could suddenly find themselves quite wealthy.

Panathenaic amphora depicting the Goddess Athena

But what was the Panathenaea actually like? Was there an order to the events?

Despite the perhaps chaotic atmosphere in the city, and the excitement that no doubt pulsed through participants and attendees, the Panathenaea appears to have been highly organized and reverent, as befitted the goddess whom the festival honoured.

Let’s take a brief look at the eight days of events during the Greater Panathenaea…

Artist impression of what the interior of the Parthenon might have looked like during the Panathenaea

There can be little doubt that, as this was primarily a religious festival, every day would have included offerings and sacrifices to the gods, and especially to Athena, whom the festival honoured.

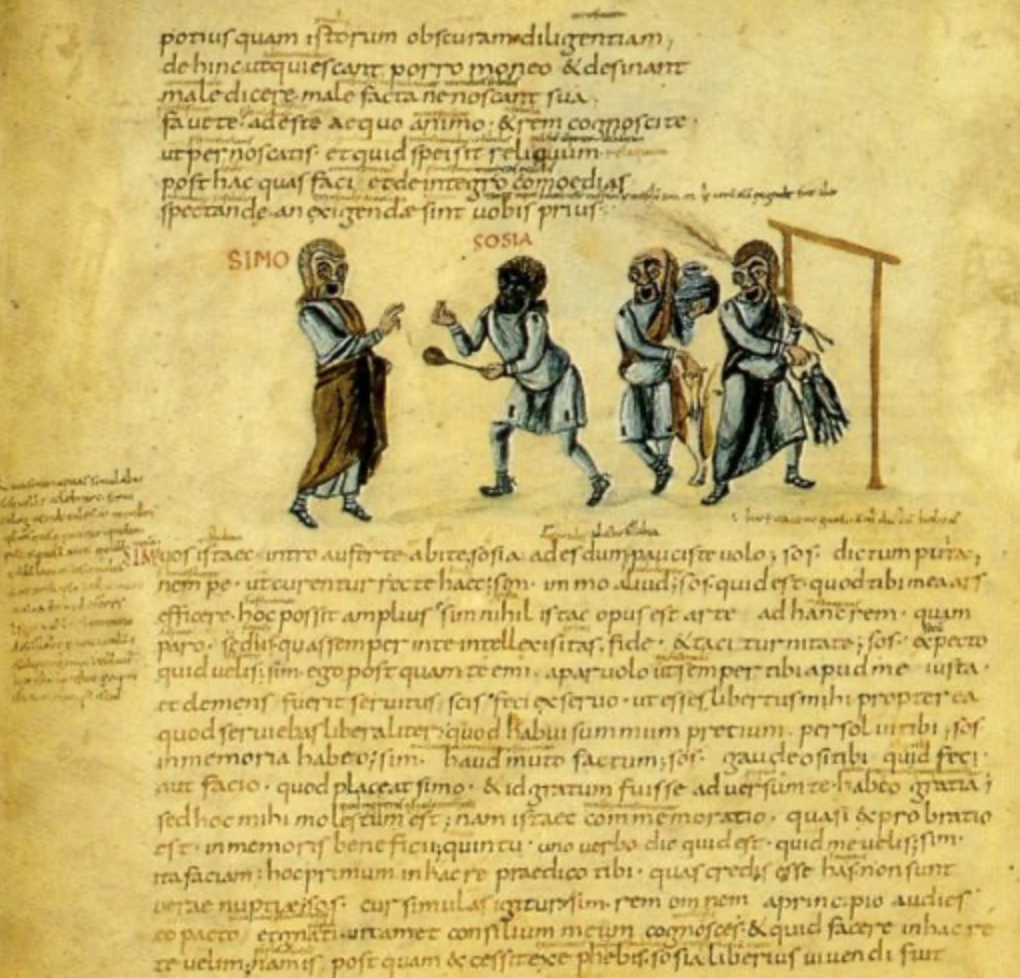

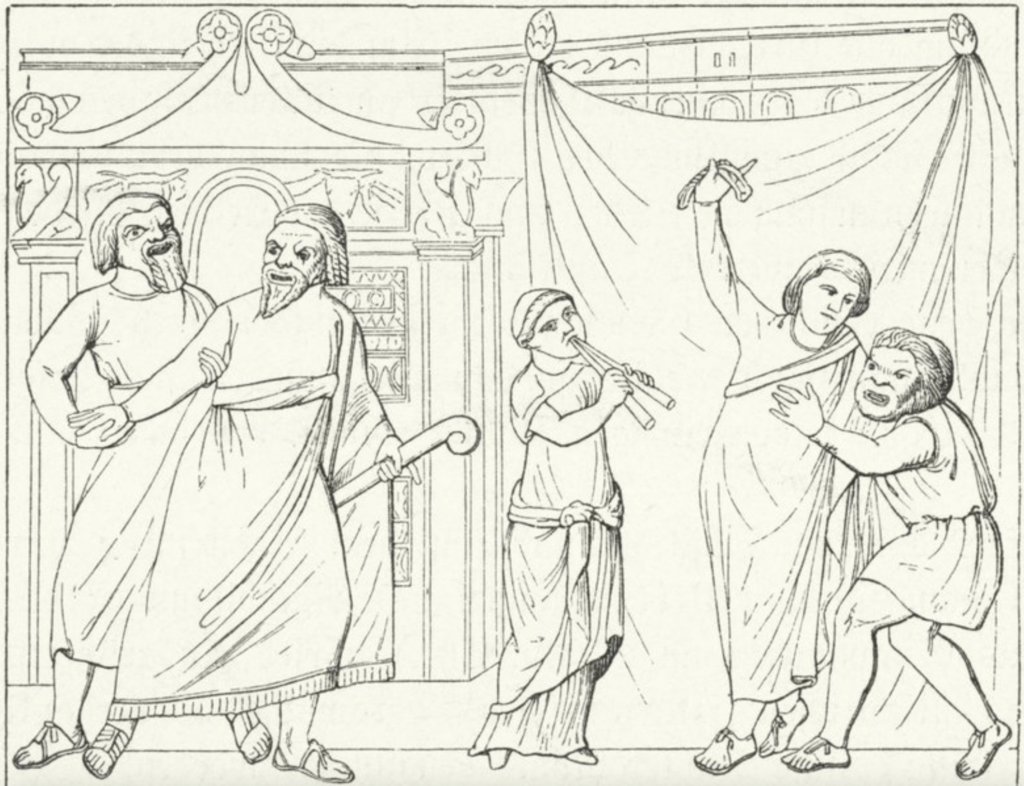

Day one of the festival was reserved for the musical and rhapsodic contests, and these were reserved only for the Greater Panathenaea.

Musical contests were instrumental and would have included musicians playing the aulus, which was a single or double reed pipe, and the cithara, which was sort of stringed lyre. In addition to contests for playing these instruments, there were also competitions of citharody, which was singing to the aulus and cithara.

The rhapsodic contest, introduced to the festival by Peisistratos, consisted of dramatic recitations of Homeric poetry from the Iliad and Odyssey. There were also poetry competitions with readings of Homer, Pindar, and Hesiod.

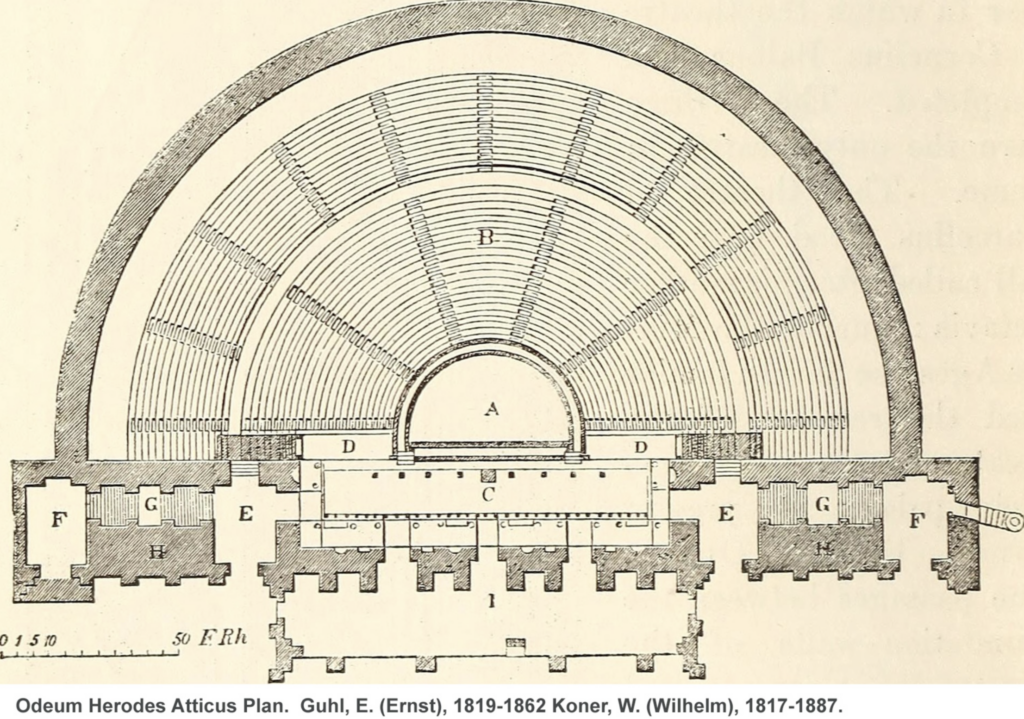

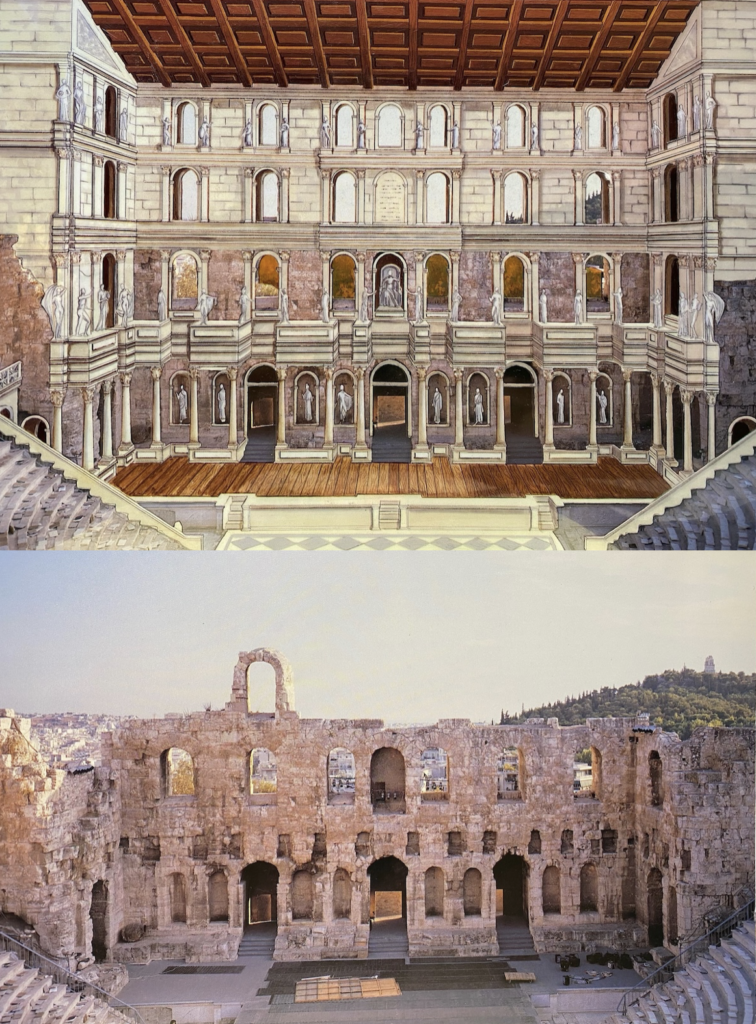

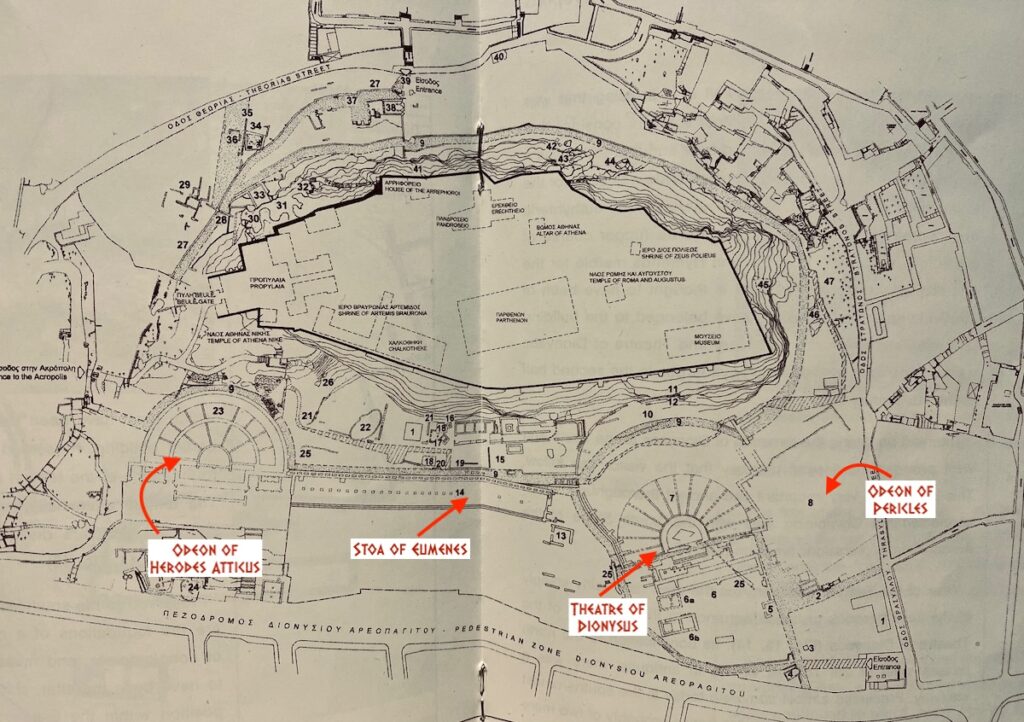

These contests were most often held in the odeon built by Pericles, which was beside the theatre of Dionysus, on the southern slopes of the Acropolis.

Ancient depiction of a musician playing the aulos

Day two of the festival was reserved for the athletic competitions for boys and youths, and these would have been held in the Panathenaic stadium which was located on the other side of the Ilissos river, between the hills of Ardittos and Agras.

Day three consisted of the athletic contests for men over twenty years of age. These would also have taken place in the stadium.

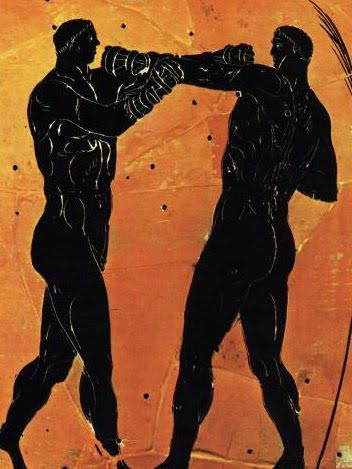

Some of the events that made up the athletic contests included the stade race, the pentathlon, wrestling, boxing and pankration.

Vase depicting Ancient Greek boxers

On day four, the highly popular equestrian events took place, and these would have included four-horse (tethrippon) and two-horse (synoris) chariot races, as well as horseback riding races, javelin throwing from horseback, and the apobates races which involved athletes jumping in and out of moving chariots at high speed. The latter is believed to be the oldest equestrian event, tradition assigning its introduction to Erechtheus.

The equestrian events would have taken place in the Panathenaic stadium and in the hippodrome to the south of the city.

The equestrian events highlighted the wealth and prestige of the participants, as owning and training horses was a costly endeavour. However, amateurs were also encouraged to participate, and their prizes are thought to have been the highest, the thinking being that they would then put the funds into horse breeding afterward.

Panathenaic amphora depicting a synoris, or two-horse chariot

Day five was when the tribal contests took place.

The first of the tribal contests was the Euandria, a procession in which leaders from tribes of Athens chose twenty-four (same number as in a theatrical chorus) of the tallest and best-looking of their tribe, and arrayed them in colourful, festive garments. They competed with the same number from an opposing tribe. This appears to have been a sort of ancient ‘manliness’ contest that emphasized qualities like physical fitness, strength, and overall excellence, things that were prized by Ancient Greek society, and closely tied to notions of citizenship and civic pride in Classical Athens.

The other tribal event was the Pyrrhic Dance. This was a sort of war dance performed again by twenty-four men from each of the tribes. It was a martial dance that symbolized readiness for battle and which was closely associated with military training, patriotism, and the worship of Athena, Goddess of War and Wisdom. The dancers wore armour, including helmets and shields, and they may also have carried swords or spears. It would have required strength, agility, and coordination, all attributes of a skilled warrior.

The Pyrrhic Dance – painting by Lawrence Talma-Tadema

On the night before the sixth day of the Panathenaea, a sacred event known as the ‘Pannychis’ took place on the Acropolis of Athens. This involved a night of songs, offerings, prayers and thanksgivings by the high-ranking priestesses who expressed joy for the birth of the Goddess Athena. Younger priestesses also danced in honour of the goddess, and toward the morning, choruses of youths and men sang songs to honour Athena.

The night of the Pannychis led into the most important and sacred day of the Panathenaea, on the 28th day of Hekatombaion. This was the day of the Panathenaic Procession, the hecatomb sacrifices at the great altar of Athena on the Acropolis, and subsequent distribution of meat to the people. There may also have been a torch race on this day.

The central event of the Panathenaea, however, was the procession which was immortalized on the Parthenon frieze on what is now known as the ‘Parthenon Marbles’.

Horsemen of the Panathenaic Procession, from The Parthenon Frieze

This was a massive event with many Athenians and non-Athenians involved. There were priestesses and priests, past and present victors in the games (athletic and artistic), as well as magistrates and other officials. There were Athenian women, and young girls who danced, and others who led sacrificial animals that had been adorned with garlands and gold-tipped horns for the goddess. There were young boys, and elders carrying sacred olive branches, military officers, soldiers and musicians and representatives of the various demes of Athens. And then there were the horsemen of the Panathenaea who are so magnificently represented on the Parthenon frieze.

The procession was not only a great show of worship for the Goddess Athena, but it was also an event in which Athenians showed their civic pride and military might.

The Peplos scene from the Parthenon Frieze

The centrepiece of the Panathenaic procession was the peplos of the goddess. This was an enormous, beautiful garment woven and embroidered for the goddess’ statue by the ergastinai, the sacred weavers, who were accompanied by priestesses. This sacred peplos of the goddess was suspended like a sail from the mast of a massive ship that supposedly moved through the streets by way of some ingenious mechanism that made it appear to sail on land. This Panathenaic ship may normally have been kept on a platform on the Hill of Agras beside the Panathenaic Stadium when not in use.

The sacred weavers, or ergastinai, from the Peplos scene of The Parthenon Frieze

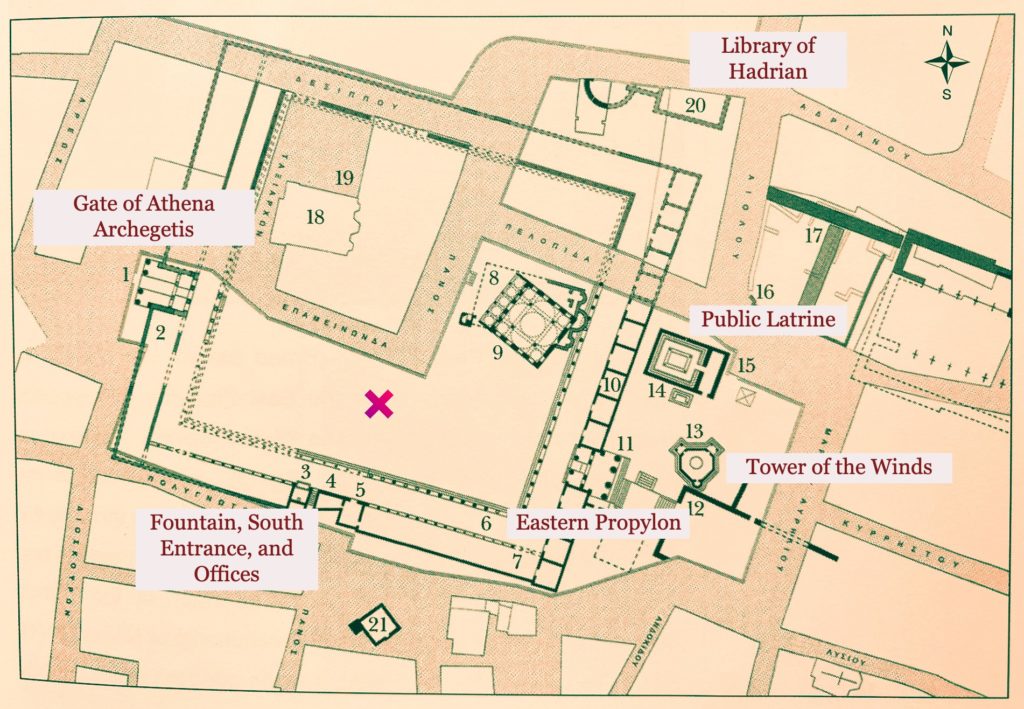

The organization of the Greater Panathenaic procession was, no doubt, a massive task, and organizing all of the people and animals involved would have required a lot of planning. Gathering all of them for the start of the procession would have required a large space. The marshalling of everyone involved in the procession happened just inside the great Dipylon Gate of the city, at the Keramikos, the location of the potters’ district and cemetery, near where the River Eridanos entered the city.

The Dipylon Gate and Keramikos – marshalling area for the Panathenaic Procession

Once everyone was had marshalled for the procession in the early morning hours, they were arranged in a specific order and processed along the Panathenaic Way, from the Dipylon Gate, through the ancient agora and up to the staircase that led to the great propylaea onto the Acropolis itself. Along the way, offerings were made at altars to the gods, including Athena Hygiaea.

When the procession arrived on the Acropolis and the sacred peplos was offered to the goddess, it would have been time for the sacrifices. This involved the sacrifice of a hundred oxen – what is known as a hecatomb – at the great altar of Athena located on the Acropolis between the Parthenon and the Erechtheum.

The sacrificial oxen in the Panathenaic Procession – from The Parthenon Frieze

One can imagine the sacrifices, including the butchering, took the better part of the sixth day of the Panathenaea. During this time, the meat was apportioned out to each deme of the city to be distributed to the people.

On the seventh day of the Panathenaea, there were boat races that took place at Piraeus, the port of Athens. These were in honour of Poseidon and Athena who had both competed for patronage of that proud city. As Athens was a mighty sea power, this event also played an important part in displaying the city’s military might.

Finally, on the eighth day of the Greater Panathenaic Games, the prizes were given to the winners and runners-up from all competitions, making some of them very wealthy and famous as a result. There were then feasts and celebrations into the night.

Parthenon temple on a sunset with pink and purple clouds. Acropolis in Athens, Greece

One can imagine the excitement that gripped the city during the Panathenaea. Civic pride would have been at an all-time high, the city sparkling and adorned in honour of Athena. Greeks from across the Greek world would have come to Athens for the event, to watch, to compete, to trade, and to pay their respects to the goddess.

We have had but a brief look at the Panathenaea in this article, but in An Altar of Indignities, we get to experience the excitement and grandeur of the Panathenaea like never before, and the reader gets fully immersed in the central event, the Panathanaic Procession, along with all of its participants.

And how does an Etrurian theatre troupe fit in to this majestic festival of Ancient Athens?

You’ll have to dive into the book to find out!

Thank you for reading.

An Altar of Indignities: A Dramatic and Romantic Comedy of Ancient Rome and Athens is now available in hardcover, paperback, and ebook editions from all major online retailers, independent bookstores, brick and mortar chains, and your local public library.

CLICK HERE to buy a copy and get ISBN#s information for the edition of your choice.