Happy New Year everyone!

Welcome to a new year for Writing the Past and Eagles and Dragons Publishing. We’re so glad you’re here to share in our love of history, archaeology, myth and legend.

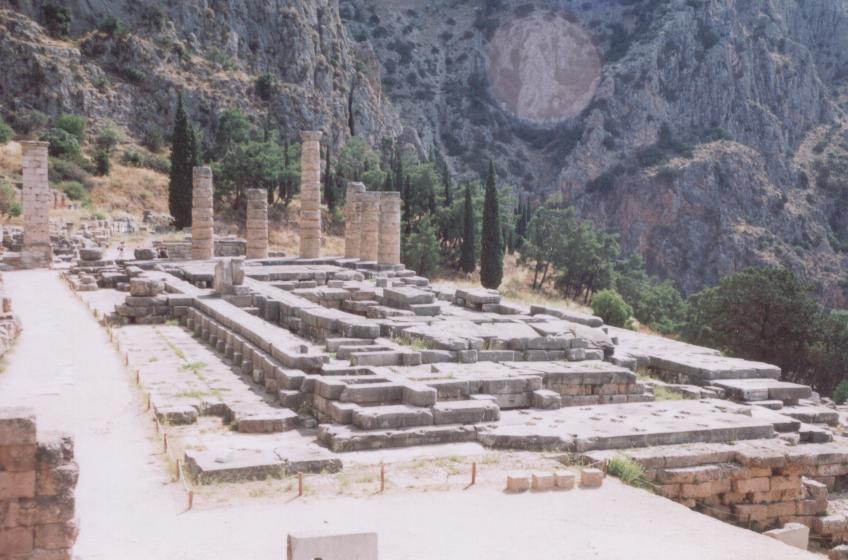

In many posts on this blog I have mentioned some of the great sanctuaries of antiquity such as Delos, Olympia and Nemea. I have touched on the special feeling one gets when walking around these places, the sense of peace that washes over you.

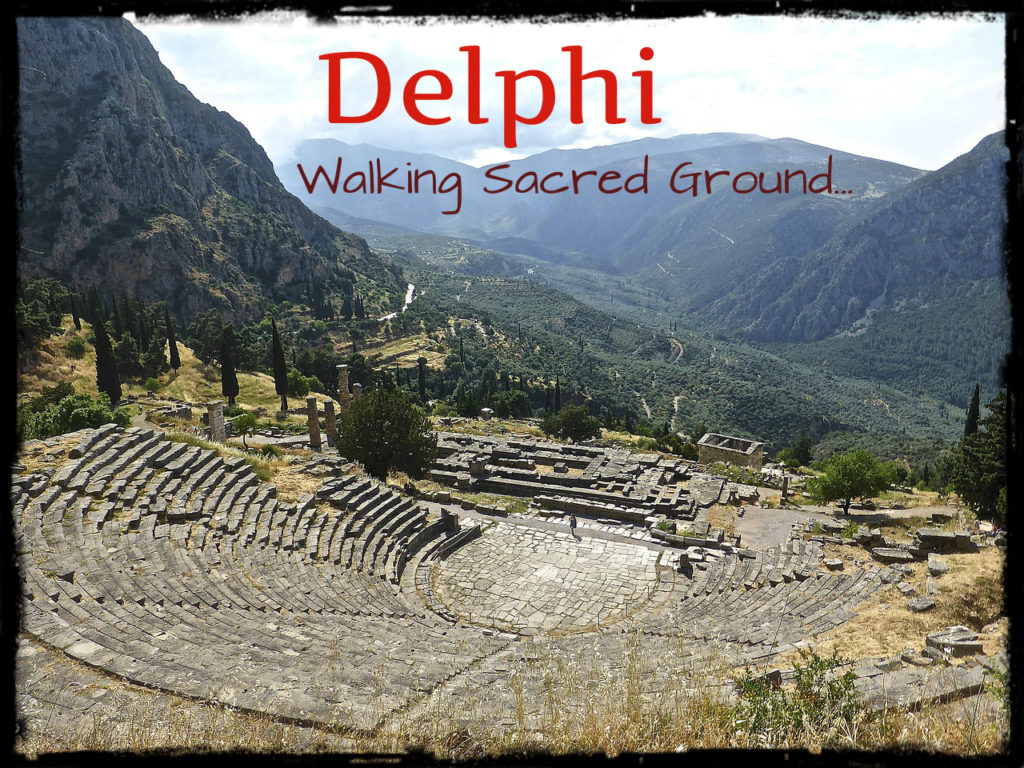

Today, we’ll be taking a short tour of one of the most important sanctuaries of the ancient world: Delphi.

Delphi was of course the location of the great sanctuary of Apollo whose priestess, the Pythia, was visited by people from all over the world who came to seek the god’s advice and wisdom.

I have been fortunate enough to visit Delphi a couple of times, and I do hope to return there someday soon. The first time I was there, the mountain rumbled throughout the night. Unused to earthquakes, my brother woke me to say that he thought there was a ghost in the room because his bed (he had the smaller one) was jumping up and down. Looking back, it’s funny that ghosts were a more logical explanation for us. Too many movies, I suppose.

But, despite frequent earthquakes, Delphi is indeed a place of ghosts. They are everywhere, the voices of the past, of the devoted, great and small.

There is something about Delphi that draws you in, that makes you want to go back again and again. Despite the throngs of picture-snapping tourists along the Sacred Way, or the hum of multi-lingual tour guides wherever you step, the sense of peace at Delphi is unmistakable.

For those with the ability to see and hear beyond the bustle, it is as though a smoky veil rises from the ground to block out the noise, leaving you with the mountain, the ruins, the voices of history.

Delphi is located in central Greece in the ancient region of Phokis. Perched on the slopes of Mount Parnassos in a spot one can well imagine gods roaming, it possesses a view of a valley covered in ancient, gnarled olive groves spilling toward the blueness of the Gulf of Corinth.

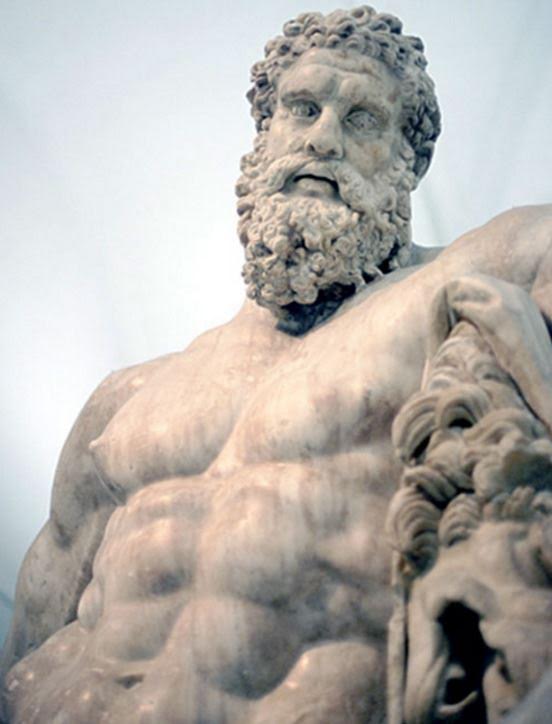

Though the site is always associated with him, Apollo did not always rule here.

Long before the Olympian god arrived, Delphi was the site of a prehistoric sanctuary of Gaia, the Mother Goddess and consort of Uranus.

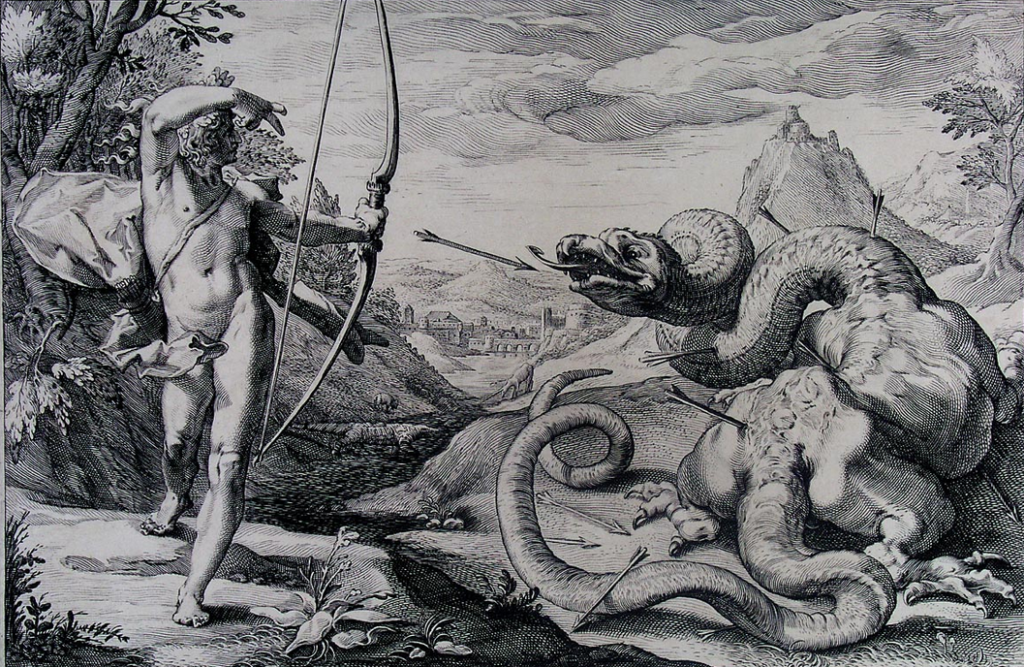

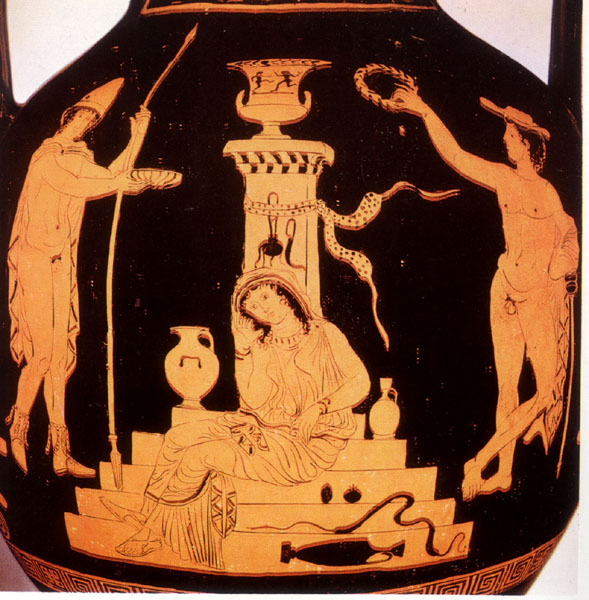

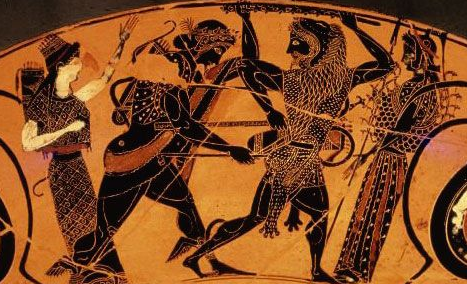

It was after Apollo, urged on by his mother Leto, defeated the great python in the sanctuary of Gaia that Delphi came under his protection.

A new era had dawned and after Apollo’s slaying of the Python, barbarism and savage custom were discarded. In place of the old religion came a quest for harmony, a balancing of opposites. Apollo was worshiped as a god of light, harmony, order and of prophecy. His oracles communicated his will and words.

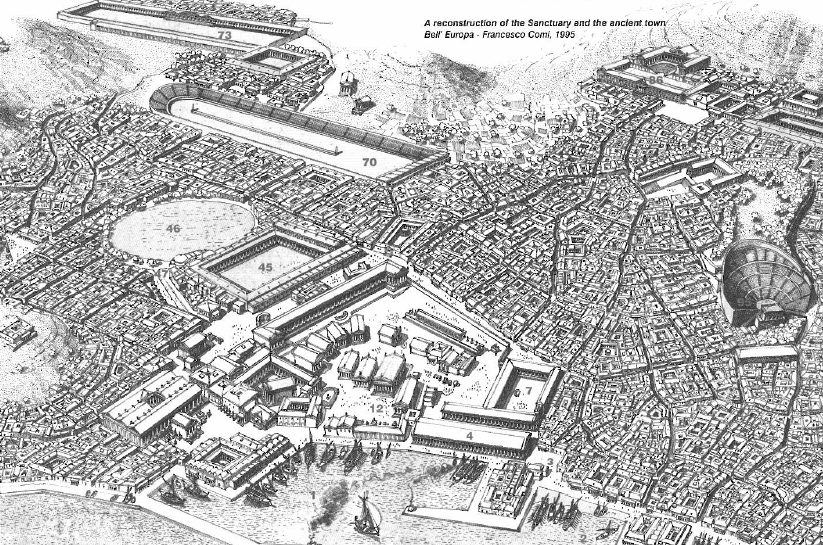

If one approaches Delphi from the East and the town of Arachova, the first thing you pass is another important sanctuary, that of Athena Pronaia. ‘Pronaia’ means ‘before the temple’. This sanctuary would likely have been visited by pilgrims first.

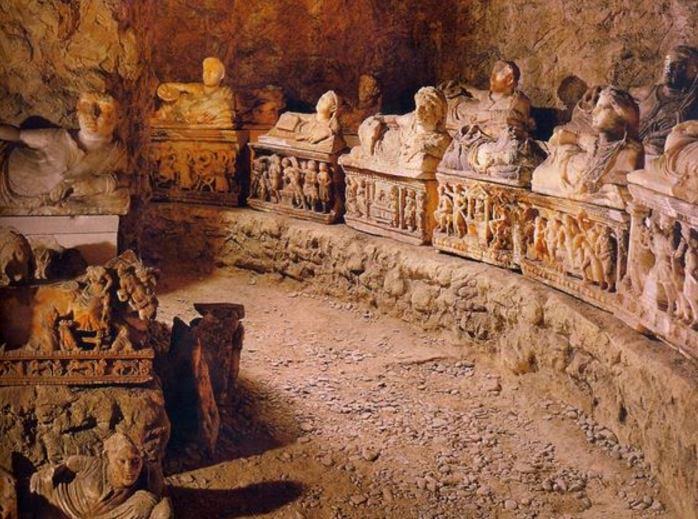

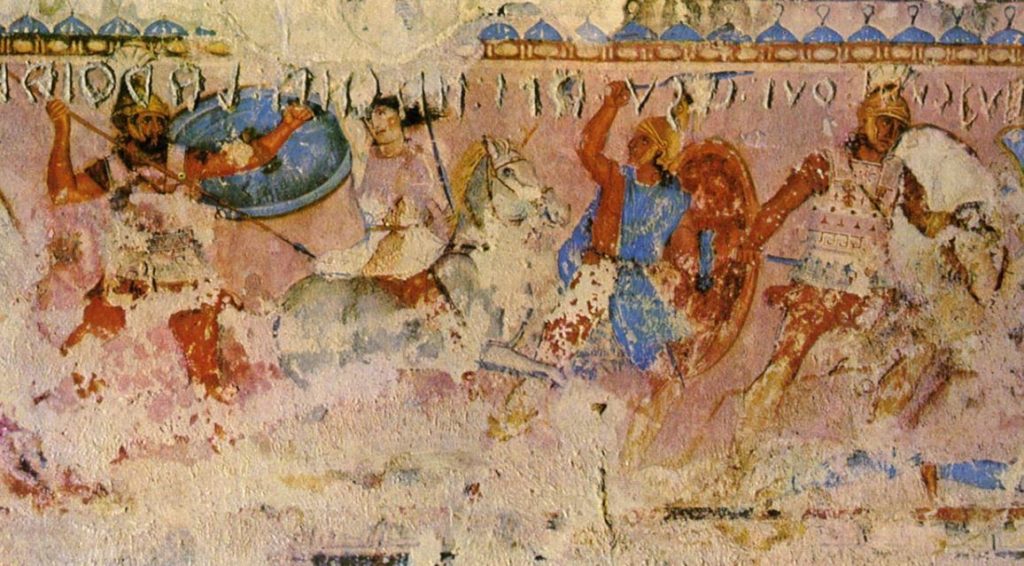

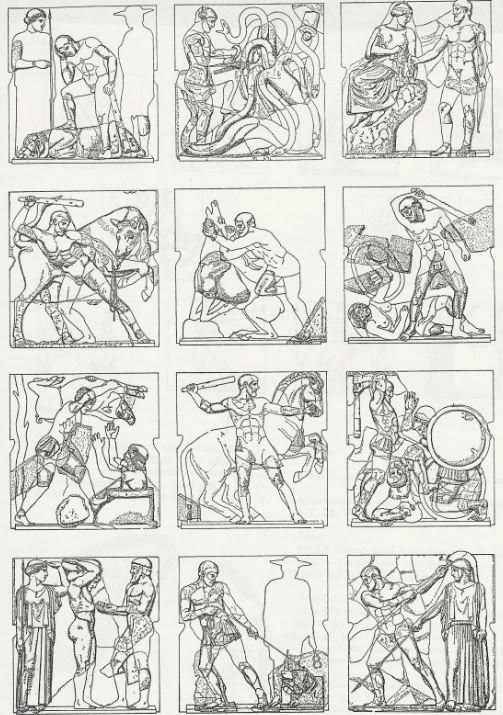

The sanctuary of Athena is farther down the mountainside from that of Apollo and located in a quiet olive grove. In its time, it contained two temples dedicated to Athena, the earliest dating to 500 B.C. There were also two treasuries, altars, and of course, one of the most picturesque ruins of ancient Greece, the round tholos temple. The latter is 13.5 meters wide and had twenty Doric columns with metopes portraying the Battle of the Amazons and the Battle of the Centaurs, the remains of which can be seen in the Delphi museum. The exact use of the tholos is uncertain though many believe it was consecrated to the cult of deities other than Apollo or Athena.

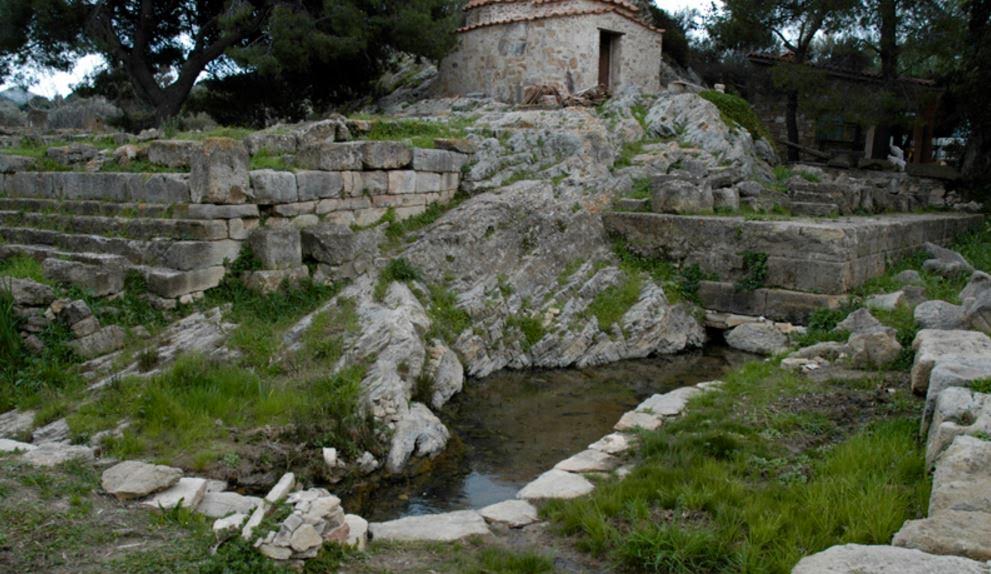

Between the two sanctuaries is the sacred spring of Kastalia, the water of which was intimately associated with the oracle. Water from here was carried to the sanctuary of Apollo and it was also here that priests and pilgrims cleansed themselves before entering god’s domain.

As part of her ritual too, the Pythia bathed in the Kastalian spring before entering the Temple of Apollo.

When the Pythia was prophesying, Delphi must have been bustling, for she was not always there. In fact, in its early days, the oracle performed her function once a year on the 7th day of the ancient month of Bysios (February-March) which was considered Apollo’s birthday. Later, the Pythia prophesied once a month, apart from the three winter months when Apollo was said to spend time in the land of Hyperborea far to the north.

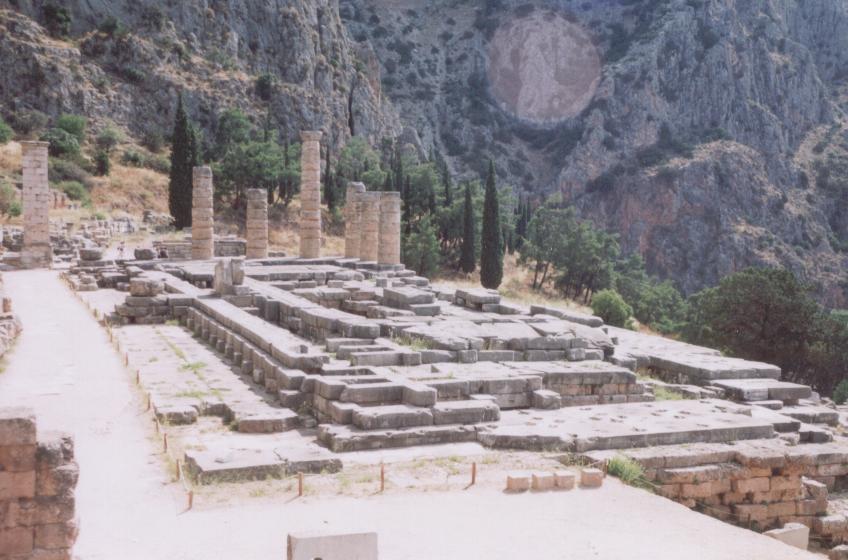

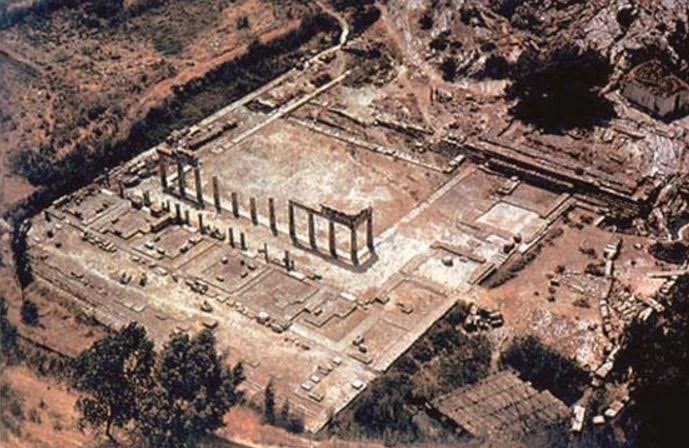

I won’t describe all the remains of the sanctuary of Apollo in detail here. There is far too much to cover and it is all fascinating. I will say that it is one of those places that every lover of history must visit.

When I think of history, the study of it, this place is what it’s all about.

On your way through the sanctuary you pass many remains, one of the most interesting being the Athenian treasury which held many rich votive offerings from the ancient polis. It is well preserved and some of the most interesting things are the inscriptions of the Hymns to Apollo and carvings of laurel leaves upon its walls.

On the left, once you leave the Athenian treasury, there are two large boulders. They look to be nothing more than rocks but these were of utmost sanctity thousands of years ago. The smaller of the two is called Leto’s Rock because it is believed that that is where Apollo’s mother stood when she urged him to slay the python. The larger rock is called the Sibyl’s Rock as that is where the first oracle (‘Sibyl’ is another name for Apollo’s oracles) stood when she came to Delphi and gave her first prophecy.

Each time I walk the marble of the Sacred Way up to the Temple of Apollo, the theatre and the stadium beyond, I am in awe. The sun seems more brilliant here, the colours richer. The buzzing of cicadas in the pine and olive trees are sounds ancient pilgrims would have been familiar with. It would have been crowded during the time of prophecy, and the line must have wended its way down the mountain to Kastalia and the sanctuary of Athena.

Every part of the sanctuary would have been adorned with bronze and marble statues, tripods, altars and other offerings from around the world. The smoke of incense and sacrifice would have weaved among it all to please Apollo and other deities who also had altars about the temple, such as Zeus, Poseidon, and Hestia, whose immortal flame was never extinguished.

The Temple of Apollo itself occupies a magnificent position and though not much remains, it is still a place of awe due in large part to the surroundings. The layout is not known exactly due to damage over time, but archaeologists have discovered that there were two cellae (temple chambers), an outer one where priests and pilgrims remained, and an inner one.

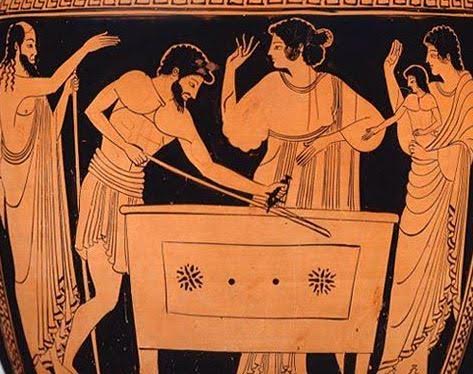

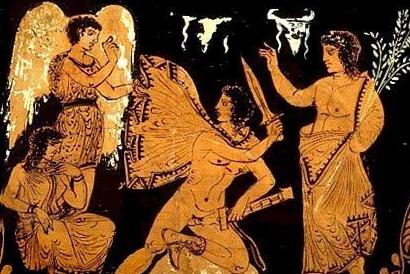

The inner cella is believed to have been the subterranean chamber where only the Pythia herself was permitted. This chamber was where she prophesied. It contained another sacred spring, the Kassiotis spring, from which she drank, a crack in the earth from which fumes emanated, the oracular tripod in which she sat, and the sacred omphalos, or, ‘navel of the earth’.

The Pythia would chew laurel leaves, inhale the fumes from the earth, and go into her trance. She would deliver her prophecy in riddles which were delivered to pilgrims.

To a modern mind, the ancients might seem absurdly superstitious, naïve even. But, in the ancient world the respect and awe with which the oracle of Delphi was viewed cannot be overestimated.

The truth of the oracle was never doubted for matters great or small. Cities, peoples, peasants and kings all sought the wisdom and guidance of Apollo through the oracle.

When I reach the top of the site and look out over the sanctuary to the valley and sea beyond, I feel that I do not want to leave. From the top of the third century B.C. theatre, or in the quiet of the stadium that once held 7000 spectators for the Pythian games, I reflect on my own journey, and on the myriad journeys of those who have come here before over the millennia.

The Stadium farther up the mountain from the sanctuary was the site of the Pythian Games and seated up to 7000 spectators

As a writer, I find people fascinating. What brought each of them to this place? What questions might they have asked? How did they receive the answers given by the oracle? I touch on this through my characters in Killing the Hydra.

Delphi was not just the site of some quaint, ancient, superstitious practices as some might see them today. This was a place of power, of beauty, refinement and of hope. In some ways, it still is.

The Pythia is gone, the sacred games long-since banished by the Christian Emperor Theodosius I. The temple and the treasures of the sanctuary have been looted, and what is left lies in romantic ruin, or on display in the museum.

However, if your path ever leads you to this ancient place on the slopes of Mount Parnassos, you may just hear the pilgrims’ prayers to the gods, the melodic utterings of the ancient hymns, and the hushed voice of the Pythia, beyond the veil of this world, as she passes Apollo’s words on to generations of mortals seeking his wisdom.

Thank you for reading…

Have you ever visited Delphi? If so, tell us what your impressions were in the comments section below.