Salvete, history-lovers!

Welcome back to The World of The Dragon: Genesis, the blog series in which we’re taking a look at the research that went into our latest Eagles and Dragons series release.

In the previous post in this blog series we looked at the Antonine Wall, the construction and the history behind it. If you missed that post, you can check it out HERE.

In Part II, we’re going to be taking a look at the prestigious career path sought by most men with political aspirations in ancient Rome – the cursus honorum.

What was the cursus honorum?

Literally, it meant ‘the course of honours’, and it referred to the sequence of official offices in the career of a Roman politician.

Late in the sixth century B.C., when Rome became a Republic, it was run (some might say ‘ruled’) by various magistrates who would form the members of the senate of Rome.

With the rise and rule of military commanders such as Sulla, Pompey, and Caesar, the magistracies of the Roman Republic became less effective, but they remained a prestigious goal for most.

From the third century B.C., there developed a specific track for a senatorial career – the cursus honorum.

In 180 B.C. a law was proposed by the tribune of the Plebs, Lucius Villius Annalis, which set down the rules and age limitations for the cursus honorum and, to an extent, perhaps sought to curb the ambitious young men of Rome.

In Tacitus’ Annals, we see reference to the law and the changes that had occurred within the cursus honorum:

With our ancestors, office had been the prize of merit, and all citizens who had confidence in their qualities could legitimately seek a magistracy; nor was there even a distinction of age, to preclude entrance upon a consulate or dictatorship in early youth. The quaestorship itself was instituted while the kings still reigned, as shown by the renewal of the curiate law by Lucius Brutus; and the power of selection remained with the consuls, until this office, with the rest, passed into the bestowal of the people. The first election, sixty-three years after the expulsion of the Tarquins, was that of Valerius Potitus and Aemilius Mamercus, as finance officials attached to the army in the field. Then, as their responsibilities grew, two were added to take duty at Rome; and before long, with Italy now contributory and revenues accruing from the provinces, the number was again doubled. Later still, by a law of Sulla, twenty were appointed with a view to supplementing the senate, to the members of which he had transferred the jurisdiction in the criminal courts; and, even when that jurisdiction had been reassumed by the knights, the quaestorship was still granted without fee, in accordance with the dignity of the candidates or by the indulgence of the electors, until by the proposition of Dolabella it was virtually put up to auction. (Tacitus, Annals, Book XI)

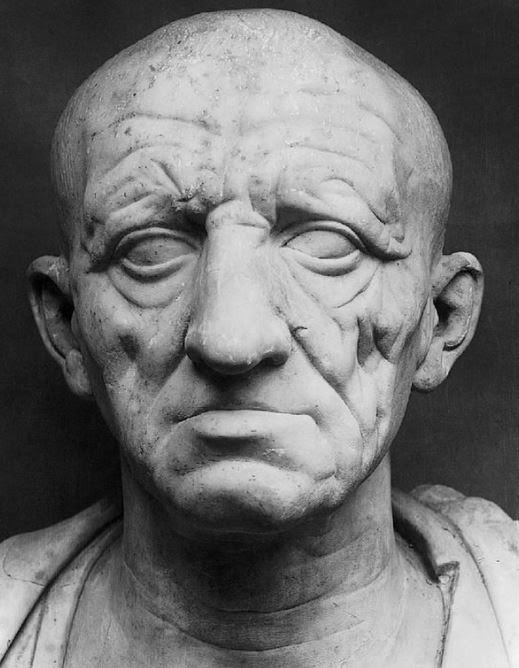

Marcus Tullius Cicero (106 – 43 B.C.)

But the proposed law, the Lex Villia Annalis, was not without its opponents, and over time, more and more young men opposed the restrictions it imposed on the cursus honorum. Many disregarded its precepts and found ways around it. Some of the men who did this were Scipio Aemilianus, Gaius Marius, Pompey, and perhaps one of the most famous men to rise along the cursus honorum, Marcus Tullius Cicero, who is supposed to have achieved each level at the youngest possible age.

But what exactly did the cursus honorum entail? What was its purpose, and how did things work?

It is actually quite complex in the details, but we will now seek to look briefly at these questions to gain a better understanding.

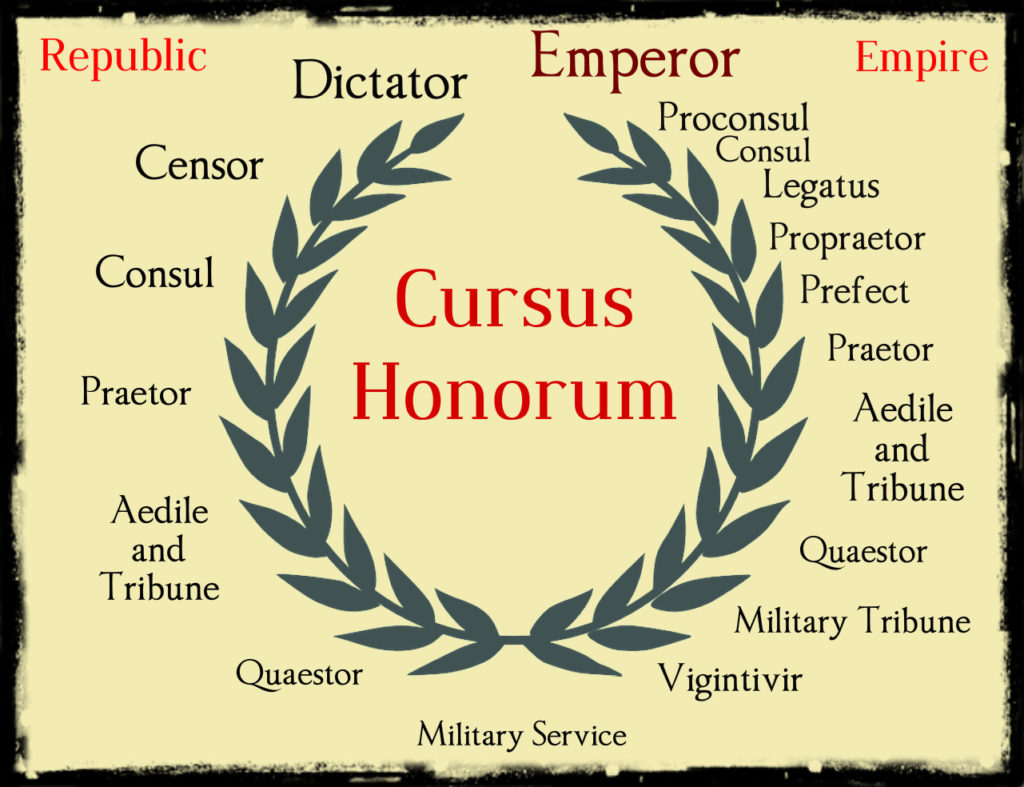

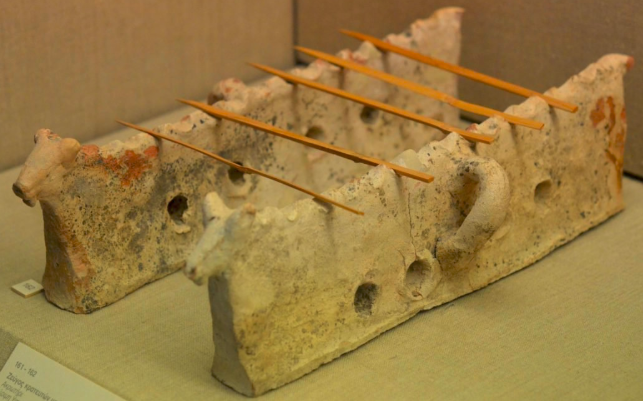

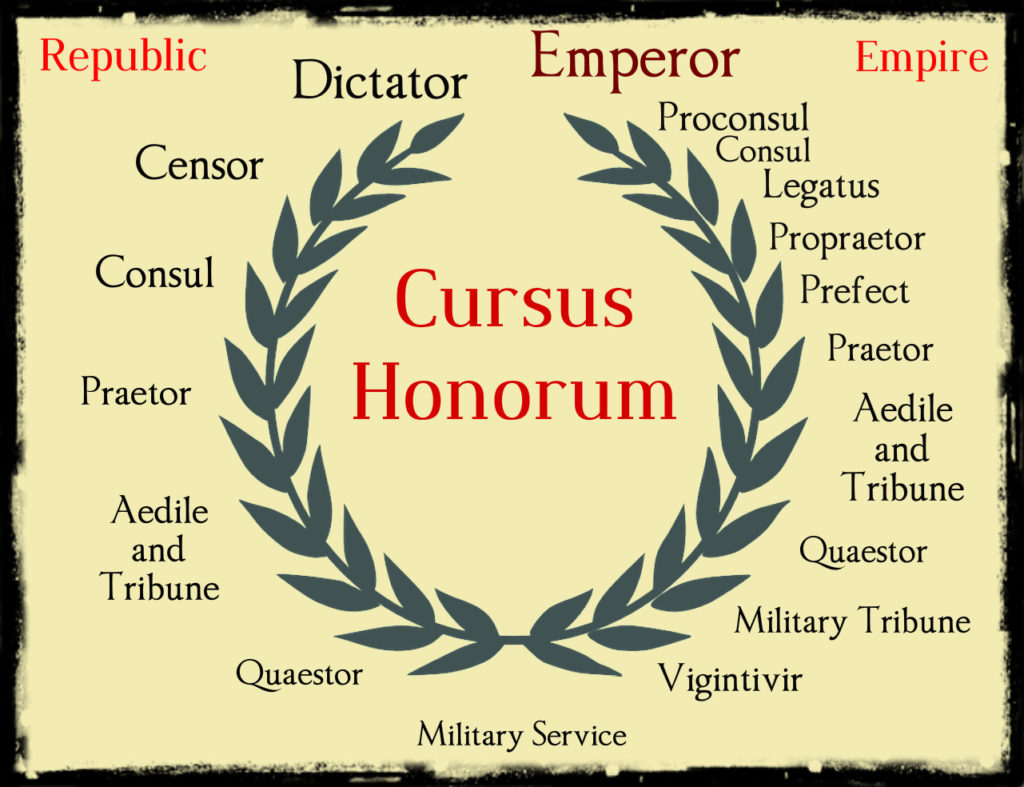

General representation of the steps along the cursus honorum during the Republican and Imperial periods. (image: Eagles and Dragons Publishing)

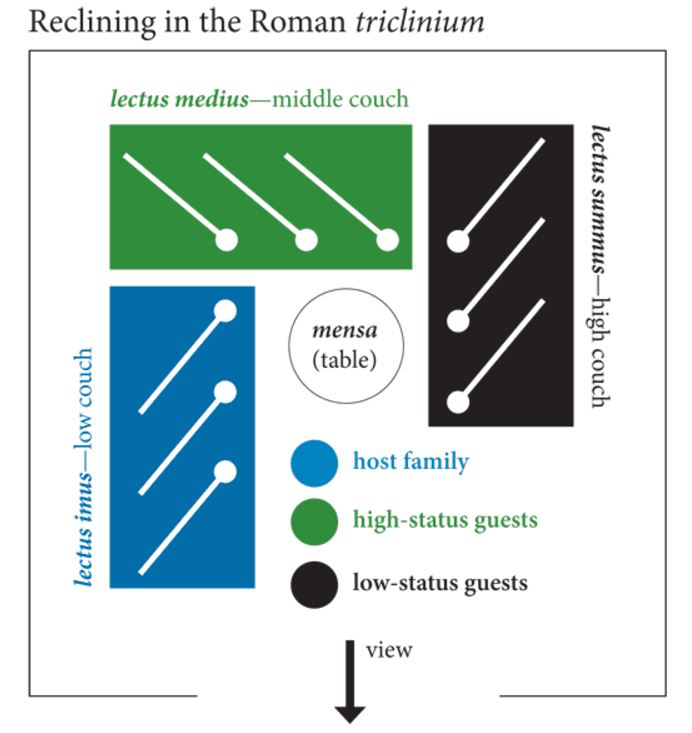

The cursus honorum gave men with political aspirations a chance to work and prove themselves at various levels of government after their general military service. Because it evolved over time, there was a difference between the cursus honorum in the Republic versus the Principate (Imperial Age).

During the Roman Republic, the cursus honorum was a path open to men of the senatorial class. After one’s military service, the positions in order of ascendency were as follows:

Quaestor: twenty financial and administrative officials in charge of public records and the treasury (aerarium). They were also paymasters for the army, accompanying generals on campaign. This was a required post for those seeking to enter the Senate. The minimum age was 30 years.

Aedile: there were four patrician aediles who administered the temple of Ceres, and later were placed in charge of public buildings, archives, and later, public games. The minimum age was 37 years.

Tribune: ten tribunes were elected from the plebeian class, and their role early on was to protect this class from the patricians. They were directly responsible to the people’s assembly and had similar duties to other magistracies. They had a veto power in the city of Rome. The minimum age was 37 years.

Painting of a young Julius Caesar, eager to climb the cursus honorum

Praetor: the praetors of Rome were the men who originally replaced the king. There were eight of these, and their role was to administer the law at Rome. They were, at first, the supreme civil judges. Later, they were to deal with legal cases with foreigners, and as Rome acquired more territories, more praetors were required. The minimum age was 40 years.

Consul: with the abolishment of the kings in 509 B.C., there were two magistrates at a time who were elected to this position. They had the duties of the king, but did not have supreme power. At first, they were only of the patrician class, but in 367 B.C., plebeians could stand for the office. Elections were held on the Ides of March (the 15th). The minimum age was 43.

Lastly, and not strictly a post required for the cursus honorum, the role of dictator was one that was granted by the Senate, through the consuls, during times of emergency. The dictator had supreme military and judicial authority, but other magistrates retained their offices during a dictatorship. It was usually granted for six months. After Julius Caesar’s murder on the Ides of March in 44 B.C., the office of dictator was abolished.

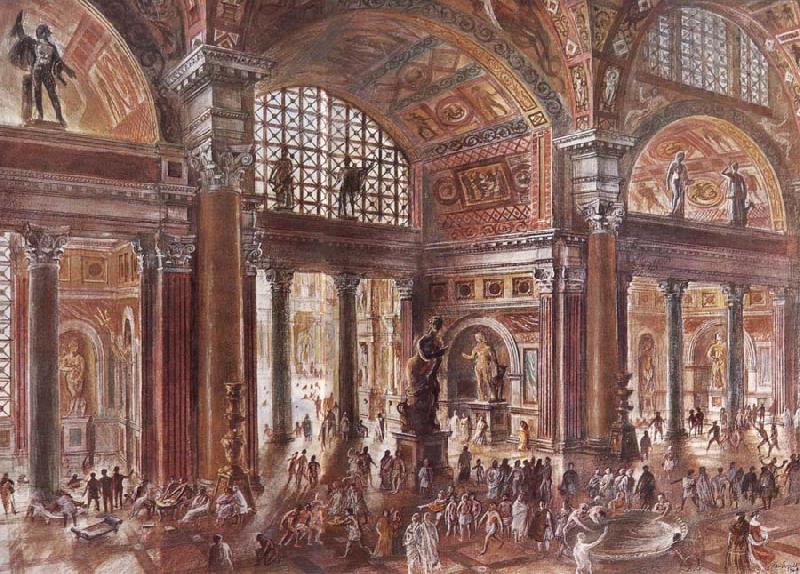

Ruins of the Basilica Julia (right of centre), one of the main public buildings, in the Forum Romanum

Now that we have looked briefly at the cursus honorum during the Republic, let us look at the course of honours during the Empire.

During the early imperial period, the cursus honorum was extended with a series of new posts being inserted between the offices of quaestor, aedile, praetor, and consul, which were retained. The role of senators was diminished, and they came to take on a more administrative role beneath the emperor. It is also important to note that the age requirements for posts were reduced, reflecting previous opposition to the old restrictions.

Here are the main positions along the cursus honorum during the Empire:

Vigintivir: there were twenty vigintiviri and these were minor magistrates who worked on various portfolios such as the mint for which perhaps only three of them would have charge of at a time. This position was the new stepping stone to get onto the cursus honorum path. The minimum age was 18 years.

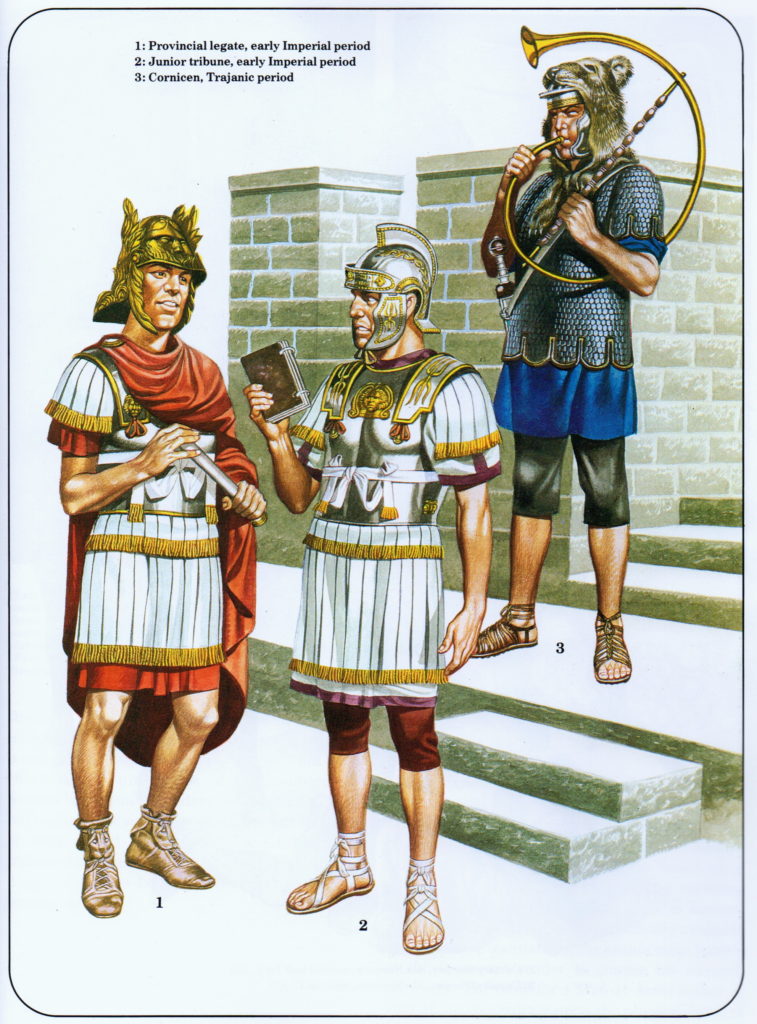

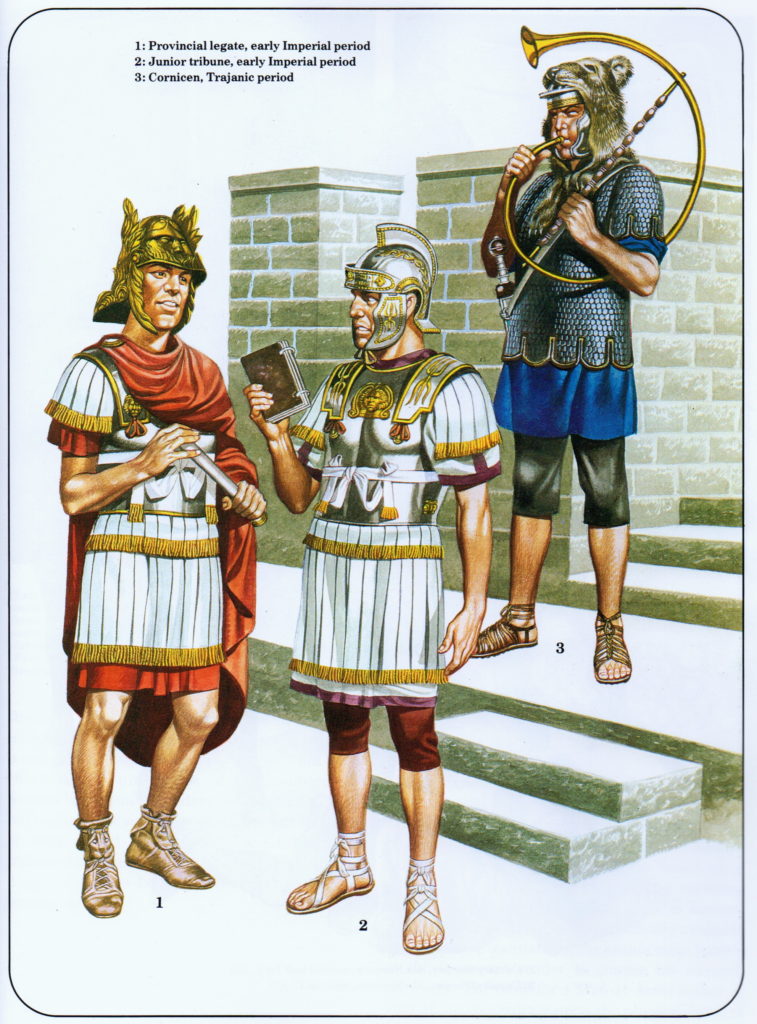

Tribunus Angusticlavius: the role of tribune during the Empire took on a more military role, with the emperors assuming the previous tribunician powers wielded by the tribunes of the Plebs during the Republic. This was one open to Equestrians (more on this class shortly), and there were five of these junior tribunes assigned to each Roman legion. The position remained until the fifth century A.D., and was another important step on the cursus honorum. The minimum age for a military tribune was 20 years.

Officers of the Imperial Roman Legions (illustration by Ron Embleton)

Quaestor: during the Empire, the number of quaestors increased as the empire itself grew in size, and though their functions might have been slightly reduced, it was still a qualifying magistracy for entry to the Senate. Minimum age was 25 years.

Aedile: this position remained during the Empire, but it was not an essential part of the cursus honorum. However, as it served an important, elected, local role across the Empire’s domains, it provided the wealthy possessors of this position with an opportunity to gain publicity for their political careers and to accumulate voters. One of their roles was to stage expensive games for the people. And we know the Romans loved their games! The minimum age was 27.

Tribunus Laticlavius: this position was reserved for Patricians who served as the senior tribune in a Roman legion. These were not usually career soldiers, but rather would-be politicians on their way up the cursus honorum. The minimum age was 27 years.

Praetor: a praetorship was an important role during the Empire, and the duties of praetorswere actually increased as opposed to other positions. They were responsible for games and festivals, and propraetors (‘in place of praetors’) were chosen for military command as governors in some senatorial provinces. This was also one of the promagistracies during the Empire. A propraetorship extended the powers and time of one in that position. The minimum age was 30 years.

Praefectus: the role of prefect was an addition to the cursus honorum during the Empire. This was normally reserved for men of the Equestrian class, and served a variety of functions from being in charge of the grain supply (praefectus annonae) to the prefect of auxiliary forces in the army, or to the high position of Praetorian Prefect. Prefects gradually took over the roles of aediles. The minimum age was 30 years. However, the minimum age for the role of urban prefect was 32 years.

Legatus Legionis: there was great power to be had with the command of a legion, and the legionary legate was at the top of the chain of military command, beneath the emperor of course. Every legion across the empire had a commanding legate. The minimum age was 30 years.

Consul: during the Empire, the consuls lost all responsibility for military campaigns. It was more of an honorary position assigned (or assumed) by the emperors, and held for just two to four months. This meant that there could be up to twelve senators in this position in a given year. As an honourary position, the consuls were permitted to go around with a bodyguard of twelve lictors, and to wear a purple-bordered toga, a colour normally reserved for emperors. There were also proconsuls at this level. The minimum age was 32 years.

A Roman magistrate followed by lictors

At this point, it is perhaps important to highlight the concepts of imperium and potestas. These were the types or classes of power held by some of the positions on the cursus honorum.

Imperium was supreme authority in matters of command in war, interpretation and execution of the law, as well as the passing of sentences of death as punishment. The positions that held imperium on the cursus honorum were consuls, praetors, the master of horse, and during the Republic, dictators. This was, perhaps, one of the great goals of the cursus honorum – to attain a position with imperium.

Potestas, on the other hand, was a general form of power held by all magistrates that allowed them to enforce the law according to the powers specific to their office.

Senate scene from the movie Fall of the Roman Empire (1964)

There is no doubt that the cursus honorum could be a complicated route, especially with the changes, exceptions and dispensations over time between the Republic and the Empire. But, it remained an important tradition in Roman public life for the upper classes.

This was further complicated by the creation and inclusion of another class in Roman society – the Equestrian class.

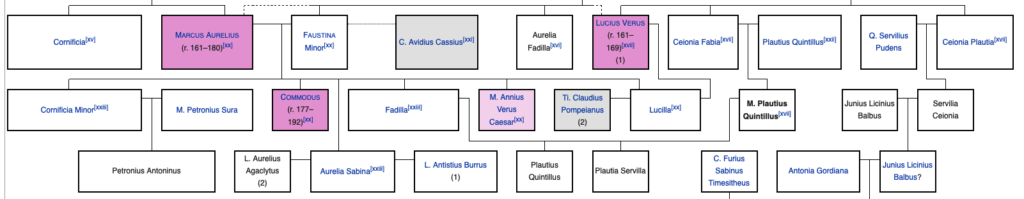

In The Dragon: Genesis, one of the main characters seeking to climb the cursus honorum is of the equestrian class.

During the Republic, equestrians were below the senatorial class, but that changed over time and the two classes became more closely allied, so much so that the equestrians became the second level of the elite in Rome.

Emperor Augustus attempted to recast the equestrians as a military class, but this motion did not pass and, instead, around the year A.D. 69, equestrians became a sort of bureaucratic elite behind the senatorial governors of the provinces.

2nd century Roman cavalry auxiliaries (illustrated by Kawaleria Rzymska)

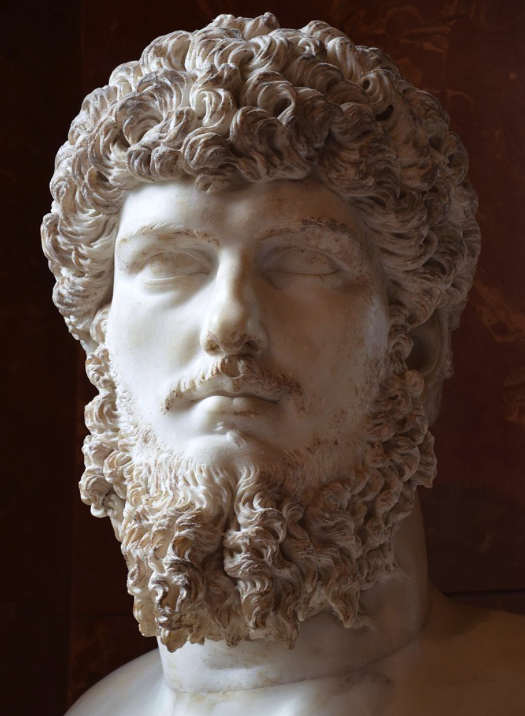

Because they posed less of a threat than the senatorial class, emperors like Commodus and Septimius Severus began to reward and rely more upon equestrians than ever before, even going so far as the grant them command of legions!

Equestrians were permitted to wear a narrow purple stripe on their togas, whereas men of the senatorial class wore a broad stripe.

For equestrians, the cursus honorum was a combination of military and administrative posts.

There were three commands for an equestrian officer in the military: a prefect of auxiliary infantry, a tribunus angusticlavius (on the cursus honorum), and a prefect of an auxiliary cavalry ala. The latter was one of the most prestigious positions available to equestrians. Equestrians could also become admiral of the navy, or a commander or prefect of the vigiles, Rome’s police and fire-fighting force.

As far as administrative positions for equestrians on the cursus honorum, they could be procurators in the provinces (such as a chief financial officer), or a prefect such as one in charge of the all-important grain supply.

As mentioned, perhaps the highest rank that could be granted to an equestrian during the Empire was one of the two positions of Prefect of the Praetorian Guard.

Praetorian Guard officers

Whereas in the past, especially during the Republic, the path along the cursus honorum was clear, the later path for equestrians was not as stringent.

Though military service was expected, it came to be less of a requirement for equestrians and others.

Many did in fact seek to be career military officers without climbing the cursus honorum. The main character is The Dragon: Genesis is such a person.

However, those men with recognizable skills could receive special dispensation from military service, granted by the emperor, so that they could work in the law courts or imperial government. Emperor Hadrian did this, as did subsequent rulers.

Christopher Plummer as the Emperor Commodus flanked by lictors and the Praetorian Prefect (Fall of the Roman Empire – 1964)

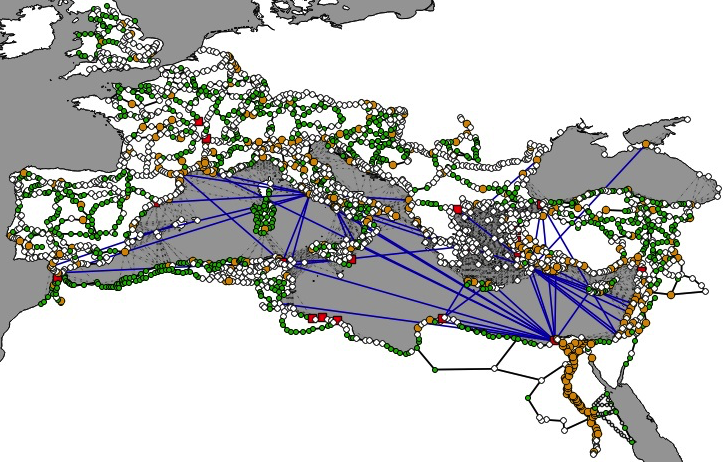

The Roman Empire was vast, and there were any number of public positions up for grabs. Times changed, as did the requirements for public office. But Romans loved their traditions, and though the magistracies of the Republic were diminished in power over time, the cursus honorum was a path that was still respected and sought after.

The course of honours could be complex, and perhaps perilous, but then again, that it seemed to have been life in the world of Roman politics.

I hope you’ve enjoyed this second part in The World of The Dragon: Genesis.

The book is not for sale anywhere, but if you are interested in reading it, you can get a copy for FREE by clicking HERE, or by clicking on the book cover image above.

Stay tuned for Part III of The World of The Dragon: Genesis, when we will be looking at the creation of the three Dacias in the Roman Empire.

Thank you for reading.