Greetings Readers and History-Lovers!

Welcome to the final post in The World of An Altar of Indignities, the blog series in which we’ve explored some of the research that went into our latest dramatic and romantic comedy set in the Roman Empire.

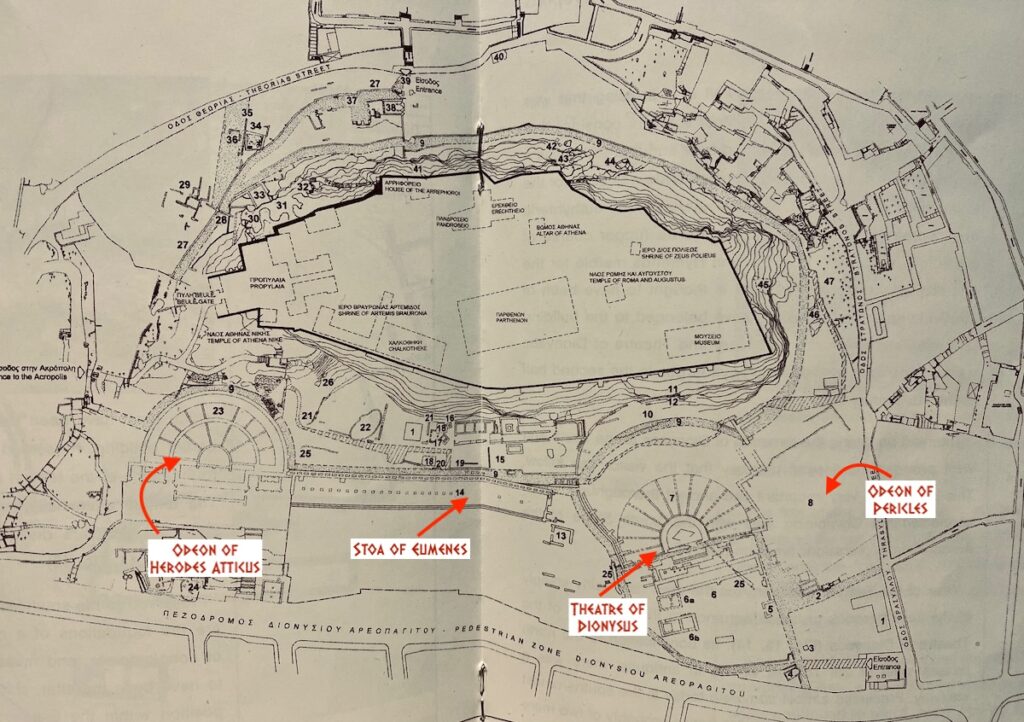

If you missed Part X on the Odeon of Herodes Atticus, you can read that by CLICKING HERE.

In Part XI, we’re going to take a brief look at the life and work of the ancient playwright who is central to the story of An Altar of Indignities: Terence.

We hope you enjoy…

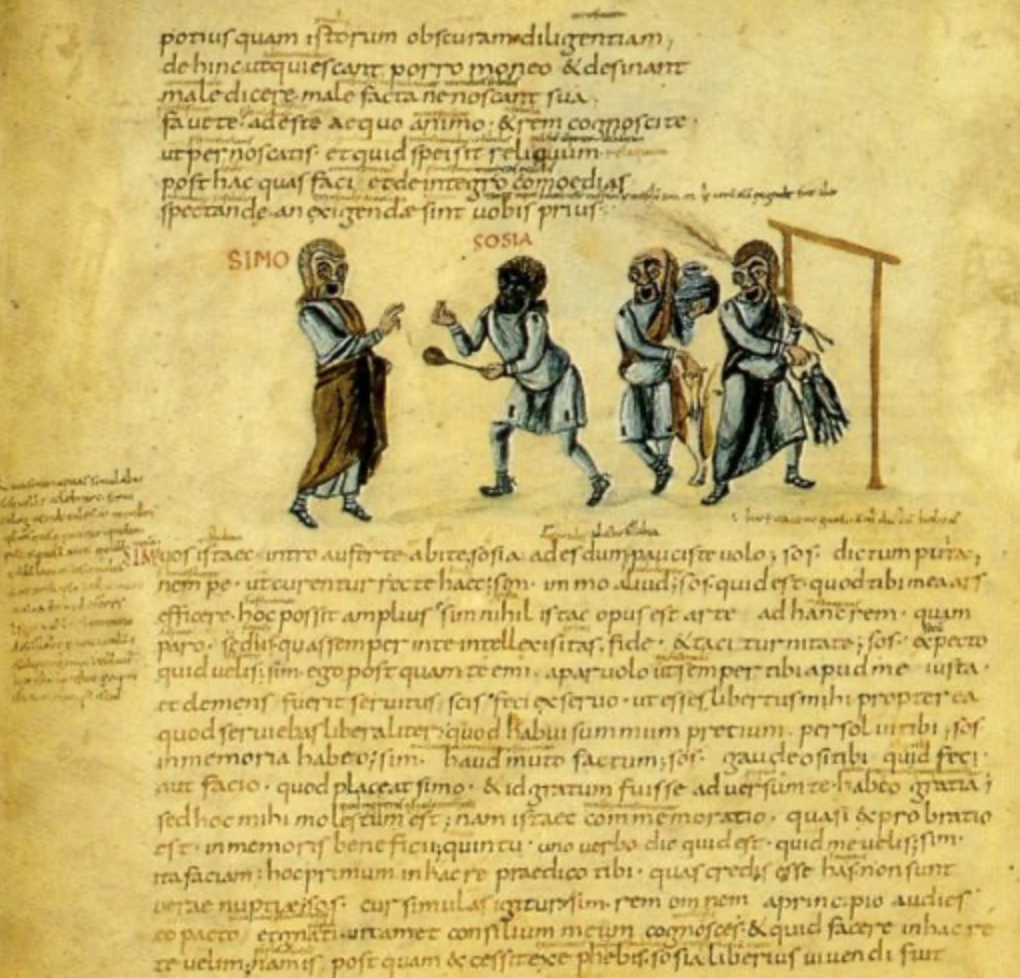

Terence, 9th-century illustration, possibly copied from 3rd-century original

Whatever fortune brings, we will patiently bear.

– Terence

The Etrurian Players series is about the life, loves, struggles, and theatrical misadventures of a troupe of players in the Roman Empire in the early 3rd century C.E. Every book in the series revolves around the production of a particular Roman play, usually at the Gods’ command.

In the first book in the series, the multi award-winning Sincerity is a Goddess, The Etrurian Players put on a production of Plautus’ Menaechmi. Plautus was, of course, one of the great comedic playwrights of Ancient Rome, and his plays were raucous and comical, using wordplay and slapstick comedy. He really was the playwright of the Roman people. You can read our article about Plautus HERE.

For An Altar of Indignities, the choice of playwright was clear. It had to be Terence, certainly, but there were a few questions that needed answering before embarking on this story’s escapade… Which of Terence’s plays would The Etrurian Players perform? How did Terence’s life and personality differ from other playwrights, and how would that affect the story? Was the cast up to the challenge? Was I?

In the end (but really, it’s a beginning!), I chose to tackle what some believe to be Terence’s most difficult play: The Heautontimorumenos , ‘The Self-Tormentor’.

The research into this play, and the personage of Terence, has been an adventure in and of itself. What little is known of Terence hints at a short and difficult life filled with both tragedy and a degree of adulation. But, like most writers, it is the work that often speaks for the person, and in reading and re-reading Heautontimorumenos several times over, attempting to plumb the complex depths of the work’s meaning, I came to see that Terence truly was – is – one of history’s greatest, most sympathetic and insightful authors.

Engraving of Terence, though he did not live to be so old…

Obsequiousness begets friends; sincerity, dislike.

– Terence

Who was Publius Terentius Afer (c. 185 – 159 B.C.E.)?

Let’s take a brief look at the man and his origins.

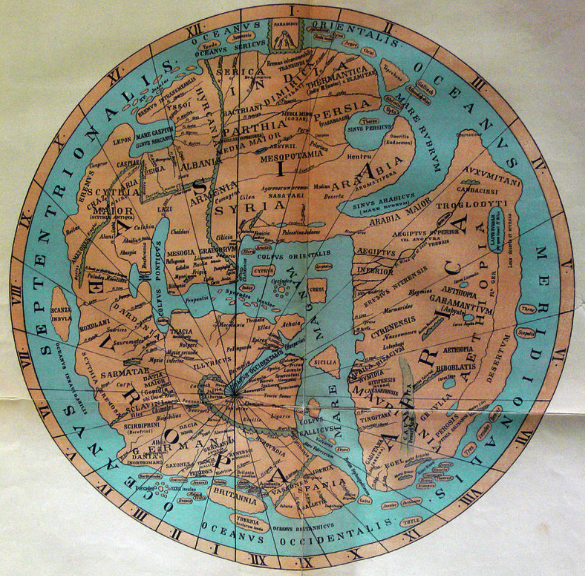

According to Suetonius in his Life of Terence, Terentius was born in Carthage in North Africa between the end of the Second Punic War and the start of the Third Punic War. Generally, his birth is thought to be around 185 B.C.E, but 195 B.C.E is also a possibility.

We do not know who his parents were, but we do know that he was born into slavery, the ‘property’ of a Roman senator by the name of Terentius Lucanus who was kind to Terence and gave the young man an education and his freedom.

A page from a manuscript of Terence, written about 825 AD

Terence was apparently a handsome young man who proved to be quite astute and brilliant. After being given his freedom and education, he made his way to Rome where he ended up moving in important and influential literary circles and was accepted into the family of the Roman consul, Lucius Aemilius Paulus, the general who had conquered Macedonia.

The story goes that at a dinner party in Rome, Terence was asked to read his own work to the famous playwright, Caecilius Statius, who was so impressed that he invited the young man to join him for dinner. Suetonius relays the events of that evening:

He wrote six comedies, and when he offered the first of these, the “Andria,” to the aediles, they bade him first read it to Caecilius. Having come to the poet’s house when he was dining, and being meanly clad, Terence is said to have read the beginning of his play sitting on a bench near the great man’s couch. But after a few lines he was invited to take his place at table, and after dining with Caecilius, he ran through the rest to his host’s great admiration.

(Suetonius – The Life of Terence)

Sometime after this entrance onto the Roman literary scene, Terence became a part of what was known as the ‘Scipionic Circle’, an informal group of Hellenophile intellectuals, poets, philosophers, and politicians who gathered around Scipio Aemilianus (185–129 B.C.E), the adoptive grandson of Scipio Africanus. This circle was deeply influenced by Greek culture, particularly Stoic philosophy, and played a key role in the Roman reception of Hellenistic thought and literature.

Artist impression of the ‘Scipionic Circle’

It is with human life as with a game of dice: if the throw you wish for happens not to come up, that which does come up by chance, you must correct by art.

– Terence

In his relatively short life, Terence wrote six comedic plays which were produced between 166 and 160 B.C.E. All of them survive.

He wrote what were known as fabulae palliatae, comedies based on Greek plays, mostly by Menander, and perhaps Apollodorus. You can read more about Roman drama by CLICKING HERE.

Terence’s six plays are as follows:

Andria (The Girl from Andros) – first performed at the Ludi Megalenses (the Festival of Cybele at Rome) in 166 B.C.E.

Hecyra (The Mother-in-Law) – first performed at the Ludi Megalenses in 165 B.C.E.

Heautontimorumenos (also Heauton-Timorumenos, The Self-Tormentor) – first performed at the Ludi Megalenses in 163 B.C.E.

Eunuchus (The Eunuch) – first performed at the Ludi Megalenses in 161 B.C.E.

Phormio (about a clever slave) – first performed at the Ludi Romani (the Roman Games) in 161 B.C.E.

and

Adelphoe (The Brothers) – first performed at the funeral games of Aemilius Paulus in 160 B.C.E.

All of the plays were produced by one Lucius Ambivius Turpio, an actor, stage manager, patron, promoter and entrepreneur who had also produced Statius’ plays. He also performed the lead in most of Terence’s plays. The music for the plays was composed by a musician, or tibicen, named Flaccus.

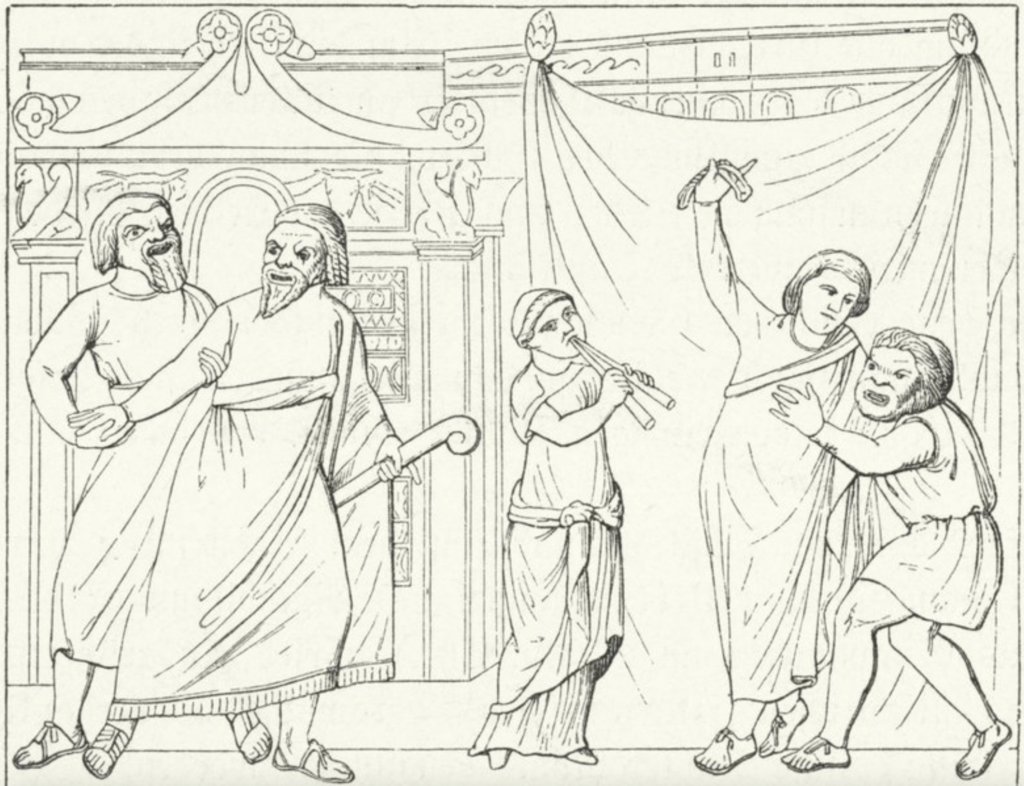

Scene from the Roman Playwright Terence’s Play Andria (engraving) by German School.

Do not do what is done.

– Terence

Terence’s work was celebrated for its refined language, realistic characterizations, and subtle humour which were a marked departure from the more boisterous style of earlier Roman comedy, including his predecessor, Plautus. His plays adapted elements of Greek New Comedy while emphasizing dialogue that was closer to natural speech. There was less musical accompaniment than in the average Roman comedy at the time, and his meters were much simpler than those used by Plautus, something that enhanced that natural feel of the dialogue. He had an uncanny ability to keep the audience’s interest.

He also used the prologus of his plays in a way that was different to others before him. Where playwrights such as Plautus used the prologus to explain the plot of the play to come, Terence used it to address criticisms of his own work such that his prologues were rhetorical in nature.

But Terence is perhaps best known for his impressive understanding of the human condition and ability to illustrate, through his dialogue and storytelling, the complexities of human behaviour. His work is truly heartfelt.

This wish to understand the human condition is perhaps best illustrated in what might be considered Terence’s most famous quote from Heautontimorumenos:

Homo sum: humani nil a me alienum puto.

I am human: nothing human is alien to me.

– Terence

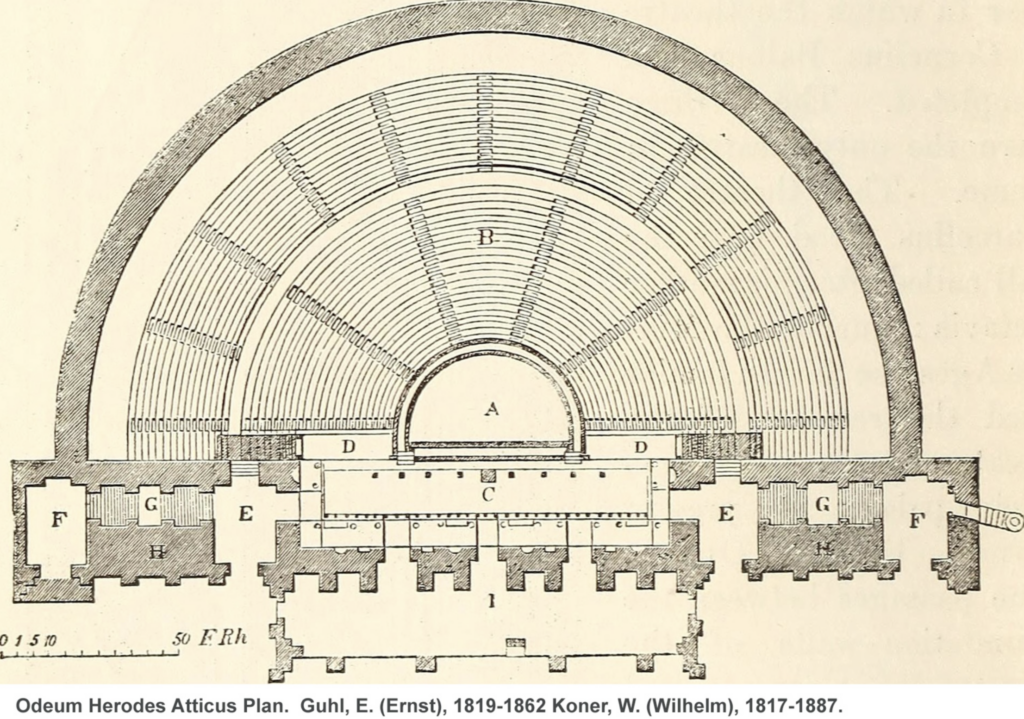

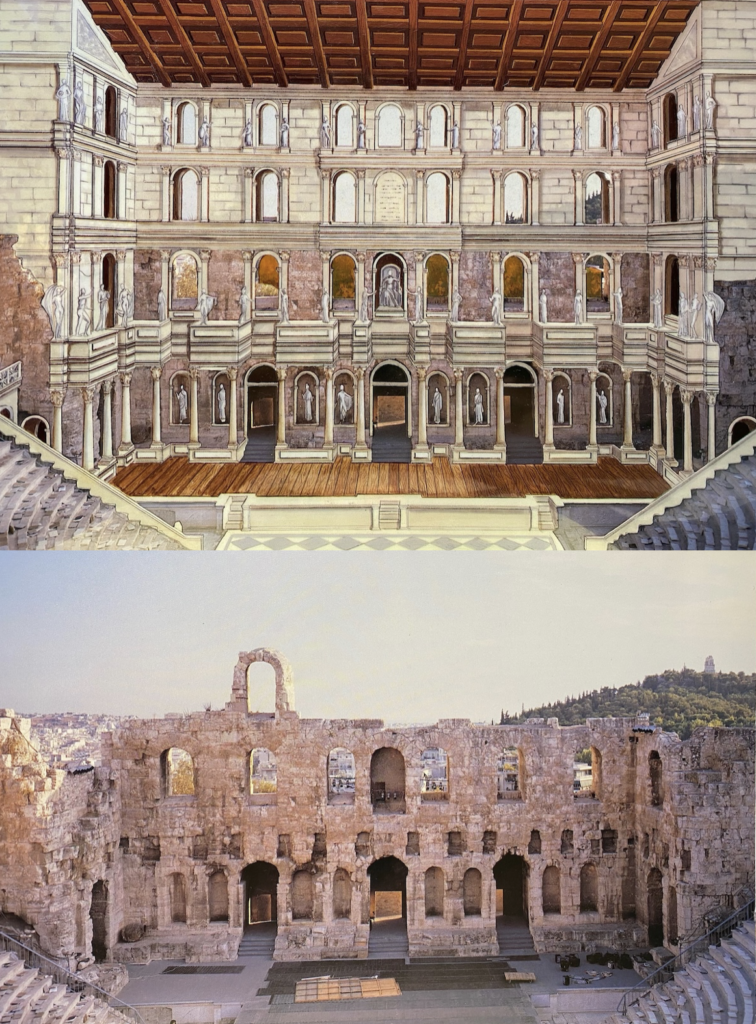

The Odeon of Herodes Atticus in Athens where the drama plays out in An Altar of Indignities

Using Heautontimorumenos (The Self-Tormentor) as the play for An Altar of Indignities was quite a deliberate choice.

As the translator, A.J. Brothers, said, it is “the most neglected of the dramatist’s six comedies… Yet the Self-Tormentor, for all its occasional imperfections, in many ways shows Terence at his best; the plot is ingenious, complex, fast-moving, and extremely skilfully constructed, its characters are excellently drawn, and the whole is full of delightful dramatic irony. It deserves to be better known.”

In truth, the play is so complex, so nuanced, that it required several readings to fully grasp all that Terence was trying to say. Perhaps in tackling this play, I discovered that there was something of a ‘self-tormentor’ in myself!

Nevertheless, I cannot imagine having chosen a different play to be featured in this novel for, in reading through it and developing an understanding of it, I came to admire the brilliance of Terence.

An image from a manuscript of Terence’s Heautontimorumenos depicting the characters Menedemus and Chremes

Heautontimorumenos, and Terence’s other plays, could be said to be ‘smart-funny’ as opposed to the slapstick humour of Plautus’ work. This is nicely illustrated in a review of the play by Sir Richard Steele, the 17th-18th century Anglo-Irish writer, in the Spectator (No. 502) when he aptly described the play:

“The Play was The Self-Tormentor. It is from the beginning to the end a perfect picture of human life, but I did not observe in the whole one passage that could raise a laugh. How well-disposed must that people be, who could be entertained with satisfaction by so sober and polite mirth! In the first Scene of the Comedy, when one of the old men accuses the other of impertinence for interposing in his affairs, he answers, ‘I am a man, and can not help feeling any sorrow that can arrive at man.’ It is said this sentence was received with a universal applause. There can not be a greater argument of the general good understanding of a people, than their sudden consent to give their approbation of a sentiment which has no emotion in it. If it were spoken with ever so great skill in the actor, the manner of uttering that sentence could have nothing in it which could strike any but people of the greatest humanity—nay, people elegant and skillful in observation upon it. It is possible that he may have laid his hand on his heart, and with a winning insinuation in his countenance, expressed to his neighbour that he was a man who made his case his own; yet I will engage, a player in Covent Garden might hit such an attitude a thousand times before he would have been regarded.”

Whereas Plautus’ plays had great appeal, especially among the Roman people, Terence’s plays seem to have appealed more to the upper educated classes. In fact, during the imperial period, long after his death, Terence was considered second only to Virgil as the most widely read Latin poet. His plays were read in Latin canonical schools on into the Middle Ages and beyond, and Terence himself was often quoted as an authority on human nature, including by St. Augustine who, though not always full of praise for the pagan playwright, quotes Terence thirty-eight times in his own works.

A gathering in Rome

As many men, so as many opinions.

– Terence

As praising as many were Terence and his work, he also had his detractors, and this is one reason for his use of the prologus in defending his work. Suetonius highlights some of the common gossip that swirled around Terence:

It is common gossip that Scipio and Laelius aided Terence in his writings, and he himself lent colour to this by never attempting to refute it, except in a half-hearted way, as in the prologue to the “Adelphoe”:

“For as to what those malicious critics say, that men of rank aid your poet and constantly write in concert with him; what they regard as a grievous slander, he considers the highest praise, to please those who please you and all the people, whose timely help everyone has used without shame in war, in leisure, in business.”

Now he seems to have made but a lame defence, because he knew that the report did not displease Laelius and Scipio; and it gained ground in spite of all and came down even to later times. Gaius Memmius in a speech in his own defence says: “Publius Africanus, who borrowed a mask from Terence, and put upon the stage under his name what he had written himself for his own amusement at home.”

– Suetonius (The Life of Terence)

Julius Caesar too criticized Terence, showing himself to not be the greatest of fans:

Thou too, even thou, art ranked among the highest, thou half-Menander, and justly, thou lover of language undefiled. But would that thy graceful verses had force as well, so that thy comic power might have equal honour with that of the Greeks, and thou mightest not be scorned in this regard and neglected. It hurts and pains me, my Terence, that thou lackest this one quality.

– Julius Caesar

Print from a manuscript of Terence’s work

Despite the few critics of his work, Terence’s plays have stood the test of time, being used to teach Latin in schools and influencing great playwrights. Even William Shakespeare is said to have been influenced by Terence’s comedy and scenic structure in plays such as The Taming of the Shrew, Love’s Labour’s Lost, Othello, and The Merry Wives of Windsor.

Despite the success in Rome of his six initial plays, Terence, for some reason, felt that he had to leave Rome and Italy, and appears to have made his way to Greece, the birthplace of drama:

After publishing these comedies before he had passed his twenty-fifth year, either to escape from the gossip about publishing the work of others as his own, or else to become versed in Greek manners and customs, which he felt that he had not been wholly successful in depicting in his plays, he left Rome and never returned.

– Suetonius (The Life of Terence)

Sadly, Terence seems not to have survived for long, leaving this world at far too young an age at twenty-five years (or thirty-five, depending on the birth date). It is supposed that either he died in a shipwreck on the journey to or from Greece, or that he died of illness when in Greece while seeking to increase his knowledge and skill in the home of the playwrights he had so admired.

Suetonius writes that he was to return “from Greece with one hundred and eight plays adapted from Menander”, but due to his death, or the wrecking of the ship that contained his new works, all of them were lost. And so, the six, brilliant plays of Terence’s that have come down to us today are all that we have of this wonderful, young Roman poet’s work.

Artist impression of Terence writing in Athens along the banks of the Ilissos river