Roman Britain

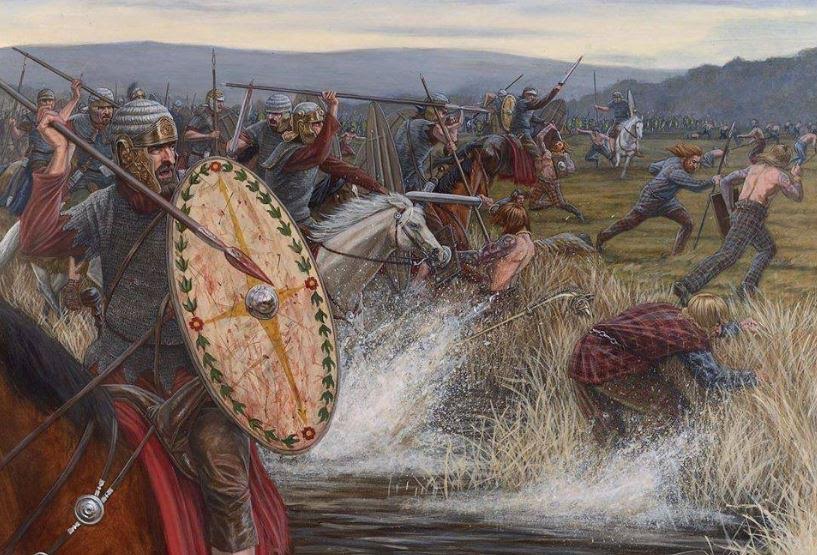

The World of Isle of the Blessed – Part VII – The Severan Invasion of Caledonia: Victory or Failure?

In the midst of the emperor’s distress at the kind of life his sons were leading and their disgraceful obsession with shows, the governor of Britain informed Severus by dispatches that the barbarians there were in revolt and overrunning the country, looting and destroying virtually everything on the island. He told Severus that he needed either a stronger army for the defence of the province or the presence of the emperor himself. Severus was delighted with this news: glory-loving by nature, he wished to win victories over the Britons to add to the victories and titles of honour he had won in the East and the West. Be he wished even more to take his sons away from Rome so that they might settle down in the soldier’s life under military discipline, far from the luxuries and pleasures of Rome. And so, although he was now well advanced in years and crippled with arthritis, Severus announced his expedition to Britain, and in his heart he was more enthusiastic than any youth. During the greater part of the journey he was carried in a little, but he never remained very long in one place and never stopped to rest. He arrived with his sons at the coast sooner than anyone anticipated, outstripping the news of his approach. he crossed the channel and landed in Britain; levying soldiers from all the areas, he raise a powerful army and made preparations for the campaign.

(Herodian, History of the Empire, XIV,1-3)

Welcome to the seventh and final part in The World of Isle of the Blessed.

In Part VI, we looked at the mystery of decapitated Roman bodies found in York, and how they may relate to Caracalla’s rampage upon taking the imperial throne after the death of his father, Emperor Septimius Severus. If you missed that post, you can check it out HERE.

In Part VII, we are going to be looking at Severus’ Caledonian campaign that is the focus of Warriors of Epona (Eagles and Dragons – Book III) and the newest release in the series, Isle of the Blessed.

First of all, why did Septimius Severus march on Caledonia? The main reason most often given by the sources is that it was something he thought would give his unruly sons, Caracalla and Geta, focus. It was something to train them for the role of emperor. Severus was a big believer in the importance of nurturing the loyalty of the legions, and so perhaps he also hoped his sons would prove themselves and, in the process, earn that loyalty.

But there had to be more to it than a training exercise for his delinquent boys.

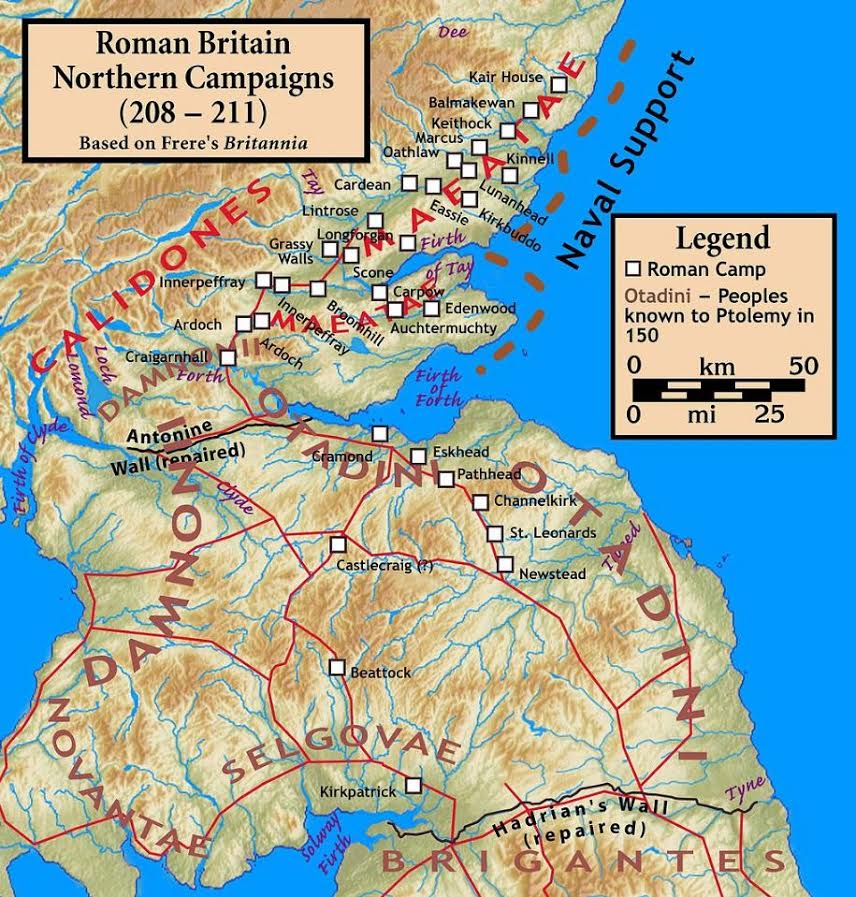

Severus’ Caledonian campaign was enormous. He moved on Caledonia with at least three full legions (the II Augusta, the VI Victrix, and the XX Valeria Victrix) as well as greater numbers of detachments and auxiliary units. When Septimius Severus took the imperial throne, he was immediately engaged in consolidating the Empire after the civil war, and then taking on the Parthian Empire. He was a military emperor, and he knew how to keep his troops busy, and how to reward them.

The Caledonians had been a thorn in Rome’s side for a long while at that time, but it was not until A.D. 208 that Severus was finally able to deal with them. And so, the imperial army moved to northern Britannia, poised to take on the Caledonians once again.

We’ve already touched on Severus’ campaign in The World of Warriors of Epona blog series. However, it’s important to note that this is believed to be the last real attempt by Rome to take a full army into the heart of barbarian territory.

Severus moved on the Caledonians with the greatest land force in the history of Roman Britain, making use of his predecessors’ fortifications (such as the Gask Ridge frontier) and roads, and penetrating almost as far as Agricola’s legions over a hundred years before.

The war may have been an opportunity to train and discipline Severus’ sons, but it seems evident that the true intention of the Caledonian campaign was to put a stop to the rebellious behaviour of the Caledonii, Maeatae and other Caledonian tribes.

Severus’ ultimate goal was the complete and permanent conquest of Caledonia.

There are two principal races of the Britons, the Caledonians and the Maeatae, and the names of others have been merged in these two. The Maeatae live next to the cross-wall which cuts the island in half, and the Caledonians are beyond them. Both tribes inhabit wild and waterless mountains and desolate and swampy plains, and possess neither walls, cities, nor tilled fields, but live on their flocks, wild game, and certain fruits; for they do not touch the fish which are there found in immense and inexhaustible quantities. They dwell in tents, naked and unshod, possess their women in common, and in common rear all the offspring. Their form of rule is democratic for the most part, and they are very fond of plundering; consequently they choose their boldest men as rulers. The go into battle in chariots, and have small, swift horses; there are also foot-soldiers, very swift running and very firm in standing their ground. For arms they have a shield and a short spear, with a bronze apple attached to the end of the spear-shaft, so that when it is shaken it may clash and terrify the enemy; and they also have daggers. They can endure hunger and cold and any kind of hardship; for they plunge into the swamps and exist there for many days with only their heads above water, and in the forests they support themselves upon bark and root…

(Cassius Dio, The Roman History 12,1)

It seems that Severus knew the Caledonian campaign would not be easy, for this was a huge offensive with a lot of military might behind it. However, one has to wonder if they knew what to expect. The Caledonii and the Maeatae were smart fighters. They knew their terrain, and their strengths. But they also knew Rome’s strengths, and so refused meet the legions in a pitched battle.

The result? A brutal guerrilla war.

…as he [Severus] advanced through the country he experienced countless hardships in cutting down forests, levelling the heights, filling up swamps, and bridging rivers; but he fought no battle and beheld no enemy in battle array. The enemy purposely put sheep and cattle in front of the soldiers for them to seize in order that they might be lured on still further until they were worn out; for in fact the water caused great suffering to the Romans, and when they became scattered, they would be attacked. Then, unable to walk, they would be slain by their own men, in order to avoid capture, so that a full fifty thousand died.

(Cassius Dio, The Roman History 14,1)

Severus’ Caledonian campaign was actually carried out in two phases. The first, explored in the novel Warriors of Epona, actually ended in a peace treaty in which Dio tells us that Severus “forced the Britons to come to terms, on the condition that they should abandon a large part of their territory.”

If Dio’s horrific number of fifty-thousand Roman casualties is to be believed (remember, ancient sources are often prone to exaggeration), then the Caledonii must have suffered even greater losses if they agreed to the terms.

It is here that one of the strangest episodes of the campaign occurred, though it had nothing to do with actual fighting, or the Caledonians.

On another occasion, when both [Severus and Caracalla] were riding forward to meet the Caledonians, in order to receive their arms and discuss the details of the truce, Antoninus [Caracalla] attempted to kill his father outright with his own hand. They were proceeding on horseback, Severus also being mounted, in spite of the fact that he had somewhat strained his feet as a result of his infirmity, and the rest of the army was following; the enemy’s force were likewise spectators. At this juncture, while all were proceeding in silence and in order, Antoninus reined in his horse and drew his sword, as if he were going to strike his other in the back. But the others who were riding with them, upon seeing this, cried out, and so Antoninus, in alarm, desisted from his attempt. Severus turned at their shout and saw the sword, yet he did not utter a word, but ascended the tribunal, finished what he had to do, and returned to headquarters.

(Cassius Dio, The Roman History, 14,3)

When they had returned to base, Severus apparently chided his son before Castor, his freedman, and Papinianus, the Praetorian Prefect, both men whom Caracalla hated and who would later feel his wrath.

It would seem that Septimius Severus, during the Caledonian campaign, was fighting a war on two fronts in a way – one in the glens and forests of Scotland, and the other at home. If the emperor was hoping that the campaign would bring his two sons closer together, he was wrong in that assessment. With Geta running the imperial administration in Eburacum (York) and Caracalla leading the troops in Caledonia, it seemed the rift between them was growing wider and wider.

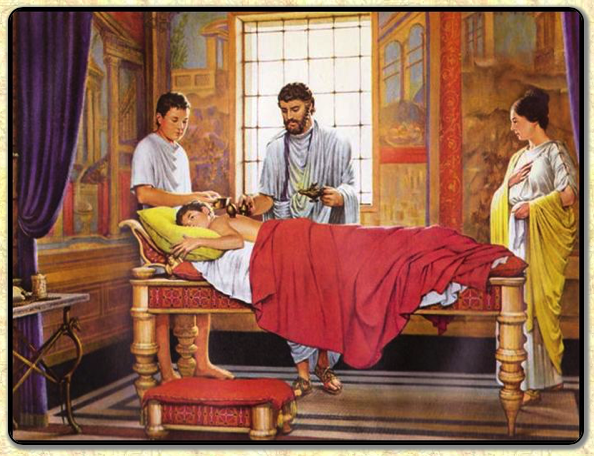

After the treaty with the Caledonians was settled, Septimius Severus, growing more and more ill and infirm, returned to Eburacum. It was during this time that Caracalla is supposed to have tried to get his father’s doctors to speed his demise, an act they refused to do at their own peril.

It was not long, however, before the Caledonians and Maeatae broke the treaty and the drums of war began to thrum once again. It is the second, bloody portion of the Caledonian campaign that takes place in Isle of the Blessed.

Cassius Dio quotes the ailing emperor’s words when he discovered that the Caledonians and Maeatae had broken the truce:

When the inhabitants of the island again revolted, he summoned the soldiers and ordered them to invade the rebels’ country, killing everybody they met; and he quoted these words:

“Let no one escape sheer destruction,

No one our hands, not even the babe in the womb of the mother,

If it be male; let it nevertheless not escape sheer destruction.”

When this had been done, and the Caledonians had joined the revolt of the Maeatae, he began to make war upon them in person. While he was thus engaged, his sickness carried him off on the fourth of February, not without some help, they say, from Antoninus.

(Cassius Dio, The Roman History, 15,1)

The Romans began visiting brutal retaliation upon the enemy then, but all ground to a halt with the death of Emperor Septimius Severus at York.

It is at this point that Caracalla and Geta became co-rulers. However, Their primary objective now was to return to Rome and garner support.

The brothers, despite the hope of their parents, tutor, and others, were anything but harmonious.

Caracalla began gathering support and power unto himself, and it is at this time that he carried out the bloody killings hinted at by the discoveries at York we heard about in Part VI of this blog series.

After the death of Septimius Severus, the Caledonian campaign came to an abrupt end:

Antoninus [Caracalla] assumed the entire power; nominally, it is true, he shared it with his brother, but in reality he ruled alone from the very outset. With the enemy he came to terms, withdrew from their territory, and abandoned the forts; as for his own people, he dismissed some…and killed others…

(Cassius Dio, The Roman History, 11,1)

The Severan invasion of Scotland was a massive campaign, involving hundreds of thousands of men. It was not nearly as large as his successful Parthian campaign in which he led thirty-three legions east, but it was one of the largest Roman operations on British soil.

50,000 Roman dead.

And how many more Caledonian and Maeatae casualties?

If Cassius Dio is correct, the numbers are staggering.

But was the campaign a victory or a failure for Rome? Was it worth it?

Severus had not only wished for the complete and permanent conquest of Caledonia, but also for the war to give his sons discipline, for it to bring them close together.

Perhaps Severus also wanted to add one more battle honour to his name – ‘Britannicus’?

If we are to believe Cassius Dio and Herodian, our primary sources for this period, we must conclude that Severus’ Caledonian campaign was more of a failure, not because Rome lost on the field of battle – indeed, despite the loss of life, they brought the tribes to their knees temporarily – but because the finalizing of the campaign was left in the hands of incapable heirs whose only concern was to return to Rome and gather power, heirs who continued to hate each other.

How many possible victories in history have been wasted in a greedy aftermath?

Caracalla and Geta abandoned Caledonia and returned to Rome with destruction and bitter enemies in their wake.

The forts of the Gask Ridge, the would-be northern capital of Horea Classis, and the Antonine wall, Trimontium and other forts were abandoned and silent once more. Rome’s allies in the fight, mainly the Votadini, were left to their own defences yet again.

The Caledonians and Maeatae had been paid off, and may have been quiet for a time, but they would rebel again…and again.

And so the cycle of powerful men wasting the lives of loyal troops in foreign wars echoes through history without end. And the same goes for the pain and suffering on both sides of any conflict.

The Severan invasion of Caledonia was just another such conflict.

And for the characters in Isle of the Blessed, the scars of that conflict will be long-lasting indeed.

Thank you for reading.

We hope you have enjoyed this blog series on The World of Isle of the Blessed. If you missed any of the posts, or would like to read them again, you can read the entire blog series by CLICKING HERE.

Isle of the Blessed (Eagles and Dragons – Book IV) is available in e-book and paperback in most major on-line retailers HERE.

If you haven’t read any books in the Eagles and Dragons series yet, you can start with the #1 bestselling A Dragon among the Eagles for just 0.99! Or get the first prequel novel, The Dragon: Genesis, for FREE by signing-up for the newsletter HERE.

Stay tuned for our next blog series about Book V in the Eagles and Dragons series, The Stolen Throne (available now).

The history, archaeology and mythology continue, and we’re thrilled to have you along for the ride.

The World of Isle of the Blessed – Part VI – Mass Murder in Roman York

After his father’s death, Caracalla seized control and immediately began to murder everyone in the court; he killed the physicians who had refused to obey his orders to hasten the old man’s death and also murdered those men who had reared his brother and himself because they persisted in urging him to live at peace with Geta. He did not spare any of the men who had attended his father or were held in esteem by him.

(Herodian, History of the Empire, XV-4)

Thus began the reign of Marcus Aurelius Severus Antoninus Augustus, the emperor more commonly known as Caracalla.

Welcome back to The World of Isle of the Blessed, the blog series in which we look at the research that went into the creation of the latest Eagles and Dragons historical fantasy novel.

In Part V, we looked at the death of Emperor Septimius Severus in York. If you missed that post, you can read it HERE.

In Part VI we are going to explore the immediate aftermath of Severus’ death, and how a mysterious archaeological discovery gives some interesting clues about the bloody beginning of Caracalla’s reign.

Septimius Severus and Caracalla (painting by Jean-Baptiste Greuze; Department of Paintings of the Louvre)

It could be argued that the death of Septimius Severus in York (Roman Eburacum) in A.D. 211 was one of the most pivotal moments in Rome’s history, that it was perhaps the beginning of the end for the Empire.

Severus had always been a strong leader who had decisively won out over his opponents in the civil war, who had conquered the Parthian Empire, and perhaps most importantly, had nurtured the loyalty of the legions.

As Cassius Dio tells us, one of the final pieces of advice to both of his sons was to “be harmonious, enrich the soldiers, and scorn all other men.”

But harmony between his sons and heirs, Caracalla and Geta, was something that would never come to be. As explored in Killing the Hydra (Eagles and Dragons Book II), after the death of Plautianus, Severus’ previous, traitorous Praetorian prefect, the two brothers were constantly at odds, running amok in Rome.

That was one of the reasons the sources give for the Caledonian campaign, that it was to give his sons a sense of purpose.

His belief in his sons, especially in Caracalla, might have been Severus’ fatal flaw when it came to the health of the Empire. Dio tells us “he had often blamed Marcus [Aurelius] for not putting Commodus quietly out of the way and that he had himself often threatened to act thus toward his son [Caracalla]”.

But Severus erred and made the same mistake as Marcus Aurelius, and set his son upon the imperial throne. Only this time, there were two heirs, and if one thing is certain, imperial power was never easily shared.

When Septimius Severus finally passed away in Eburacum, (Roman York) on February, A.D. 211, Caracalla made his bid to secure power immediately.

As have other rulers in Rome’s history, he began by eliminating his perceived enemies, those who posed an immediate threat.

This did not include his brother Geta at first, for Geta was also well-loved by the men of the legions as Severus’ son, and Caracalla needed the legions’ loyalty.

Others were not so fortunate.

As Herodian tells us in the quote above, Caracalla began to “murder everyone in the court”.

But how and where did he do this?

In the early 2000s, a gruesome discovery beneath a patio in York hints at what might have happened.

What this archaeological discover entailed aligns well with what we are told of Caracalla’s bloody start to his reign, and hints at the madness or paranoia that already had a hold on the young emperor.

As it turns out, the discovery in York entailed the burials of over 30 male skeletons, all of them between the ages of twenty and forty.

The strange thing about these skeletons was that they were all decapitated…executed. And they date to the beginning of Caracalla’s reign.

The heads of the bodies were places in strange positions – some by the feet or between the legs and some face down. There are even two skeletons in which the heads were exchanged, the one put with the other.

Ancient Romans took death and burial seriously, but in this instance there is little respect shown to the skeletons.

From the forensic evidence, experts believe that these men were executed by beheading.

Some of the bones display horrific injuries too. A few show a single, clean cut through the vertebrae of the neck, but others show a brutal end with one skeleton displaying eleven separate cuts to the neck on all sides, plus a massive head trauma.

So, who were these men that Caracalla would strike so brutally at them?

The theories vary, but it seems likely that most of them were Praetorians who had been loyal, not only to his father, but to Papinianus, the Praetorian Prefect. These were men Caracalla felt he did not have their loyalty. But there were possibly others among the slain.

It is quite possible that among the dead are the remains of the doctors who refused to help speed the emperor’s passing when requested by Caracalla. Also, Severus’ loyal freedman, Castor, is a possible victim, for he was often at odds with the young Caesar and had Severus’ confidence. Another who had helped to rear Caracalla and Geta, and who is said to have often annoyed the former, was their tutor, Euodus. Was he also among the decapitated dead?

One of the decapitated bodies found as if thrown unceremoniously into the ‘grave’ (photo: York Archaeological Trust)

Whoever the victims of this massacre in Roman York were, they had incurred Caracalla’s anger in some way, and he made them pay for it before dumping their mangled corpses in a cemetery outside the walls of the city.

In Isle of the Blessed, this horrific event is one of the more grisly episodes in a history that, quite frankly, you just can’t make up.

Often, history is unbelievable, and when turning it into fiction, the stakes have to be raised.

So, what happens to the protagonist, Lucius Metellus Anguis, during Caracalla’s rampage in Isle of the Blessed?

You have to read the story to experience it for yourself.

Thank you for reading.

To learn more about the Severan invasion of Scotland as well as the archaeological discovery of the decapitated bodies at York, be sure to watch the Timewatch documentary below.

Tune in next week for the sixth post in The World of Isle of the Blessed when we will take a brief look at the Caledonian campaign and wether it was indeed a victory or not.

Isle of the Blessed is now available in e-book and paperback formats on major retailers. CLICK HERE to learn more.

The World of Isle of the Blessed – Part IV – The Court of Severus in Eburacum

Welcome back to The World of Isle of the Blessed. We are at the midway point in this blog series about the history, archaeology and research that are related to Isle of the Blessed, the latest novel in the Eagles and Dragons historical fantasy series.

Last week in Part III, we took a tour of Glastonbury, Somerset and some of the sites that are featured in the novel. If you missed it, you can check it out HERE.

This week, in Part IV, we will be meeting some of the main players in the story, the members of Septimius Severus’ imperial court in Eburacum (modern York) when he spent three years there during the Caledonian campaign. Fans of the series will already be familiar with some, but others will be new, but no less interesting or important to this part of the story.

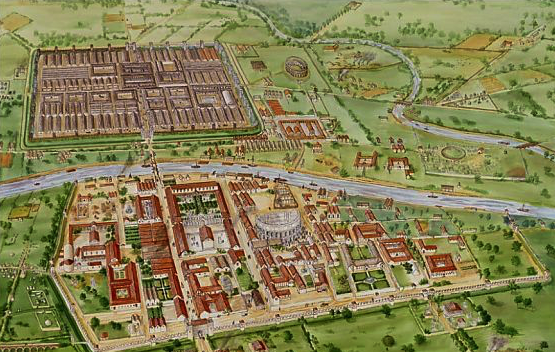

During the Caledonian campaign, Septimius Severus moved much of his government to Eburacum, the provincial capital of Britannia Inferior, the northern half of the province.

His entourage would have included not only his wife, sons, and other family members, but also an army of slaves, civil servants and more.

With the court moving to Eburacum for over three years, the city would have been bustling with activity. The markets would have been full with merchants and suppliers coming from around the Empire to provide for the great influx of civilians as well as the many thousands of auxiliary troops who came to Caledonia in addition to the legions that were already posted there.

Like any imperial court, however, there were camps with different intentions and interests working in the background. The glens of Scotland were not the only battlefields, and the period of Severus’ rule, perhaps especially during the Caledonian campaign, was a crucial time for the Empire.

So who were the main players at the imperial court, and where did their loyalties lie?

Severus had been ‘dying’ for years, but now, it seemed, the end was near, and the vultures were circling.

First, let us look at the family of Severus himself.

The Severans were a very interesting family and not without their tales of violence and greed and uniqueness of character. The period is not marked by something so brutal (not yet!) as the psychotic reign of Caligula, but there are certainly many more dimensions. It is a time of militarism, of a weakened Senate, a time of spymasters in various camps. It is a time marked by the rise of lower classes, the presence of powerful women and, over it all, a blanket of religious superstition at the highest levels. Many believe that it is this period in Rome’s history that marks the true beginning of the end of the Roman Empire.

In writing the Eagles and Dragons series, it has become obvious that Septimius Severus (A.D. 193-211) was, perhaps, one of the better emperors in Rome’s history. Sure, he was not Antoninus Pius (few were), but he was far better than say, Tiberius.

He was the son of an Equestrian from Leptis Magna in North Africa. When Commodus was killed in A.D. 192, Severus was governor of Pannonia. When the Praetorians decided to auction the imperial seat a short time later, Severus’ legions declared him Emperor. He subsequently defeated his two opponents who had also declared themselves Emperor: Clodius Albinus and Pescennius Niger. A purge of his opponents’ followers in the Senate and Rome made Severus sole ruler of the largest empire in the world.

Septimius Severus was a martial emperor, the army was his power and he knew how to use it, how to keep the legions loyal and happy. During his reign, he increased troops’ pay and in a radical move, allowed soldiers to get married. Severus was good to his troops, his Pannonian Legions and victorious Parthian veterans, some of whom fought for him in Caledonia. He promoted equestrians to ranks previously reserved for aristocrats and lower ranks to equestrian status. There was a lot of mobility within the rank system at the time due to Severus ‘democratization’ of the army. Remember, this was an emperor who favoured his troops, especially those who distinguished themselves. However, as Lucius Metellus Anguis discovers in Isle of the Blessed, there are prices to be paid. No favour is free, and being close to the imperial court can be perilous.

One of the most interesting characters of the period is Empress Julia Domna. She appears as one of the strongest women in Rome’s history, an equal partner in power with her husband who heeded her advice but also respected her. Julia Domna was the first of the so-called ‘Syrian women’, hailing from Antioch where her father had been the respected high priest of Baal at Emesa (Homs in modern Syria).

Julia Domna was also highly intelligent, known as a philosopher, and had a group of leading scholars and rhetoricians about her. They came from around the Empire to be a part of her circle, to win commissions from her. Her strength also bought her a great many enemies, including the previous Praetorian Prefect and kinsman to Severus, Gaius Fulvius Plautianus. In Caledonia however, years after the death of Plautianus, with her husband’s health deteriorating rapidly, she must have worried a great deal about the dual succession of their sons, Caracalla and Geta, both of whom brought a tenseness to the court.

By all accounts Caracalla and Geta, Severus’ heirs, were both at odds much of the time. The two brothers seem to have tolerated each other’s presence and competed fiercely back in Rome, even in the hippodrome where at one point they raced each other so aggressively on their chariots that they ended up with several broken bones, almost leaving their father without a successor.

Caracalla seems to have been the favourite of the empress, though in later years Julia Domna does come to Geta’s defence, however much in vain.

One of the main reasons the sources give for the Caledonian campaign was that Septimius Severus believed it would be good for his sons, a way to teach them, give them focus, and prepare them to succeed him together. If anything, however, the angry chasm between the brothers grew worse the more their father’s light faded.

Caracalla, the older of the two brothers and about twenty-two at the time of the campaign, was the more martial of the pair. While Geta was appointed to administer the province from Eburacum, Caracalla went north to fight alongside the troops.

Did resentment build in the young Caesar as he fought, away from the court? Suspicion? Paranoia? Perhaps it was all of that and more? During the first phase of the Caledonian campaign, when Severus was about to agree to peace with Argentocoxus, the Caledonian leader, it is said that Caracalla nearly murdered his father in front of everyone, an episode that plays out in the previous novel, Warriors of Epona.

Caracalla was eager for the imperial throne, so much so that, as Herodian tell us, “he tried to persuade the physicians to harm the old man in their treatments so that he would be rid of him more quickly.”

And what of Geta, Severus’ younger son and heir?

He seems to have been entrusted with much as far as the administration of Britannia during the Caledonian campaign, so he must have been skilled to some extent. However, from what little we know of him, he was not the survivor that his brother was, and most likely lacked the ambition that was needed in the imperial court.

He was respected by people at court and by the army, but this was perhaps due more to his parentage and position than his actions over the course of his short life.

Whatever impact Geta had over the years, perhaps the most prominent was his ability to anger his brother by way of his mere existence.

One of the main players at the imperial court was Aemilius Papinianus, or ‘Papinian’ (A.D. 150-212), Prefect of the Praetorian Guard.

Papinianus is a fascinating man, a man of intelligence who was thrust, perhaps unwillingly, into one of the most powerful and perilous positions in the Roman Empire.

After the death of Gaius Fulvius Plautianus in A.D. 205, as told in Killing the Hydra, Severus appointed Papinianus as prefect of the guard. Before that, he had been a brilliant jurist (lawyer), legal expert, and had served as Severus’ main secretary. He was Syrian, and it seems likely that he was a cousin of the empress, Julia Domna. Perhaps that is why he was so trusted.

Papinianus, in his day, wrote many legal texts and was a great believer in the equity of the law. But what must he have thought to see the risk of all that Severus built over the years – with his advice – turning to ash after the succession of Caracalla and Geta?

It must have been dark days for the reluctant Praetorian Prefect.

Lurking in the shadows of Papinianus was his long-time apprentice and fellow jurist, Domitius Ulpianus, or ‘Ulpian’ (A.D. 170-223).

It seems that Ulpianus was also a brilliant lawyer who served as a secretary under Severus (beneath Papinianus), and then became Papinianus’ right hand when the latter was made Praetorian Prefect.

Interestingly, Ulpianus’ writings were very influential on Roman law and later, on the laws of Medieval Europe.

But what must he have thought constantly playing second to Papinianus? Did the apprentice ever feel jealous of the master, or try to outdo him? We don’t know for certain, but what we do know is that he survived the tough years ahead, and so he must have been close to Caracalla. In fact, Ulpianus went on to become sole Praetorian Prefect in A.D. 223 under Emperor Severus Alexander. He must have been a survivor.

There are two other men who played a very prominent role at the imperial court, who had the emperor and empress’ utmost trust, but who had also incurred the wrath of Caracalla.

Euodus, was the long-time tutor of Caracalla and Geta, and was still with the family when they went north during the Caledonian campaign. It seems that life was easier when the young caesars were smaller, but as the years went by and the animosity between them grew worse, Euodus’ job was more to try and nurture harmony between the brothers, something he evidently failed at.

This man may have felt he had much influence at court, and perhaps he did. But his constant attentions, his preachings perhaps, would prove to be more of an aggravation to Caracalla. Euodus would pay for it.

Likewise, Castor, who was Septimius Severus’ most trusted chamberlain, had a prominent role at court. He was a freedman of Severus’, elevated from a lowly rank to having the emperor’s ear, and his confidence, on a daily basis.

It is said that Castor was one of the imperial court members who most annoyed Caracalla. He was there at every turn, even when Severus reprimanded his son for attempting to kill him in front of the Caledonii at the end of the first campaign.

As Cassius Dio tell us, both Castor and Euodus did not fare well when Severus finally passed.

There were others who played a crucial role in the imperial court and would have been present at Eburacum during Severus’ time there.

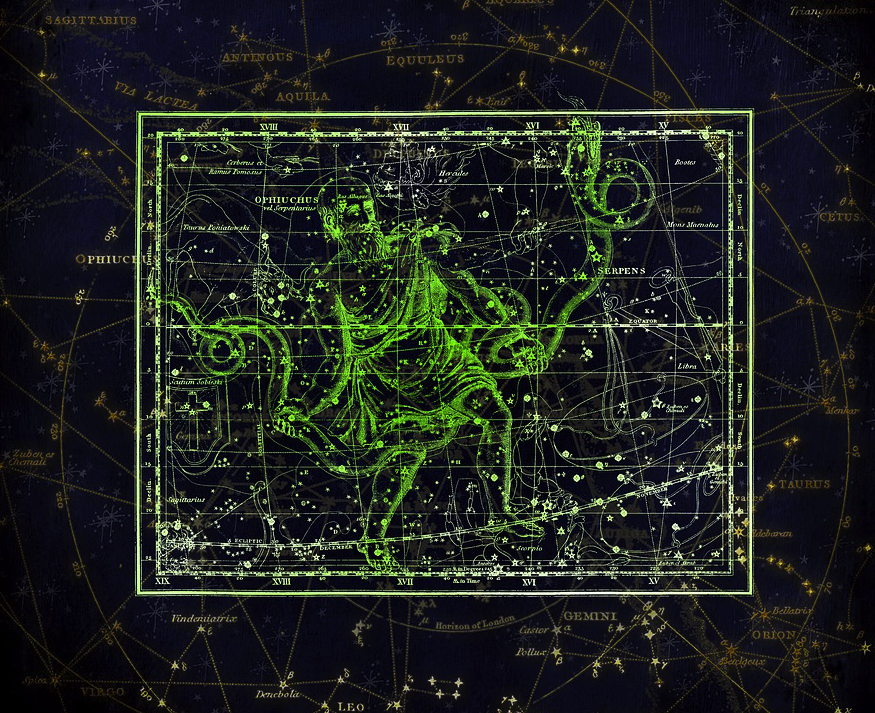

As almost fanatical believers in astrology, Septimius Severus and Julia Domna would have had their primary astrologer, possibly named Artemidoros, with them at all times. He would have done daily readings for them, advised on any action, civic, personal, or military, and was probably the one who determined the date of Severus’ death before they even left Rome.

The sources say little to nothing about him, but his role would have been an important one, his influence upon the emperor and empress great.

As someone who would have been ill for many years, Septimius Severus would have required medical attention on a daily basis, especially at the end. His physicians would have been there, at the heart of imperial politics, hearing and seeing much, including Caracalla’s aforementioned request to speed his father’s passing.

These doctors, who had refused Caracalla’s request (threat?), likely grew extremely wary as their patient’s health deteriorated more by the day in the British climate.

To this point, we’ve discussed the people whom we know to have been present at the imperial court. In truth, however, there would have been many hundreds (thousands?) who were a part of the imperial machine and civil service who were present in Eburacum. After all, the Empire was being administered from there during that time.

There are also some other key players who may have been present.

It is quite possible that Julia Domna’s sister, Julia Maesa, may have been present. After her sister, Julia Maesa was perhaps one of the most influential of the ‘Syrian Woman’. She and her daughters, Julia Soaemias Bassiana and Julia Avita Mamaea (mother of later Emperor Severus Alexander) would be extremely influential in the years to come.

It would not be surprising if Julia Maesa were present at court, close to the heart of things. She was apparently close to Caracalla too, and this would have protected her and her daughters. She survived until A.D. 226.

With much of the government following the emperor, one has to wonder if there were not also a certain number of senators present in Eburacum as well.

If so, it is possible that Cassius Dio was there. As the primary, contemporary source for the reign of Septimius Severus, it would not be surprising if he were present in Britannia for at least a portion of the campaign.

Then there is Caracalla’s wife, Plautilla, and her brother Plautius. Were they present? Or did Caracalla want to keep her as far from him as possible, as it was said that she was ever an annoyance to him in previous years.

If the names of Plautilla and Plautius are somewhat familiar to you, it may be that that is because they are the children of Gaius Fulvius Plautianus, the traitorous Praetorian Prefect who was dispatched by Caracalla and others in a plot in A.D. 205, with Julia Domna no doubt working toward that end in the background.

As for his wife and brother-in-law, Cassius Dio said that Caracalla had them killed when to took power, but whether it was immediately, or upon his return to Rome is not stated.

Another person who may have been in Eburacum for much of the time, and who may have found his work partially hi-jacked by the presence of the imperial family and the administrations of Geta, was Gaius Junius Faustinus Postumianus. He was the provincial governor of Britannia Superior, based in Londinium.

Faustinus was an officer in the army previously, before being appointed governor. What did he think about the presence of the imperial court in Britannia, or the waging of war at the borders of his province? No doubt the situation brought him many benefits, but also many headaches, especially when Severus passed from the world.

Of one thing we can be certain, and that is that an imperial court was not a place for the faint of heart.

Who survived, and who fell? Did being close to Severus’ sun mean you would get burned, or thrive?

For a writer of historical fiction, these are interesting questions to be explored with different answers for each player in the drama.

If anything, life at the court of Severus in Eburacum would have been anything but dull, despite the fact that they were on the virtual edge of the Empire.

Thank you for reading.

Isle of the Blessed is now available in e-book and paperback from all major on-line retailers. If you haven’t read any books in the Eagles and Dragons series yet, you can start with the #1 bestselling A Dragon among the Eagles for just 0.99! Or get the first prequel novel, The Dragon: Genesis, for free by signing-up for the newsletter HERE.

The World of Isle of the Blessed – Part II – Roman Lindinis: The Small Town with Big Ambitions

Welcome back to The World of Isle of the Blessed, the blog series in which we take a look at the research, history and archaeology that went into the latest novel in the Eagles and Dragons historical fantasy series.

In Part I, we looked at the hillfort of South Cadbury Castle which is one of the major settings of the book. If you missed that post, you can read it HERE.

In Part II, we’re going to be taking a look at another place that plays an important role in Isle of the Blessed: Roman Lindinis.

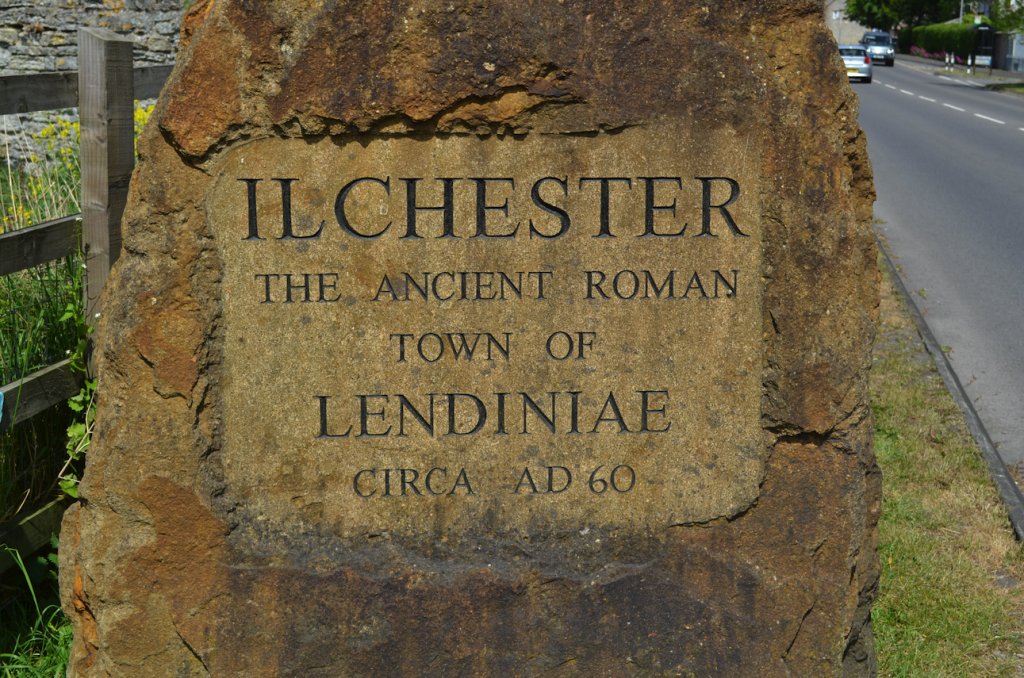

The settlement of Lindinis (also known as ‘Lendiniae’), as it is known in the seventh century Ravenna Cosmography (a list of place names from India to Ireland) is actually modern Ilchester, in Somerset, England.

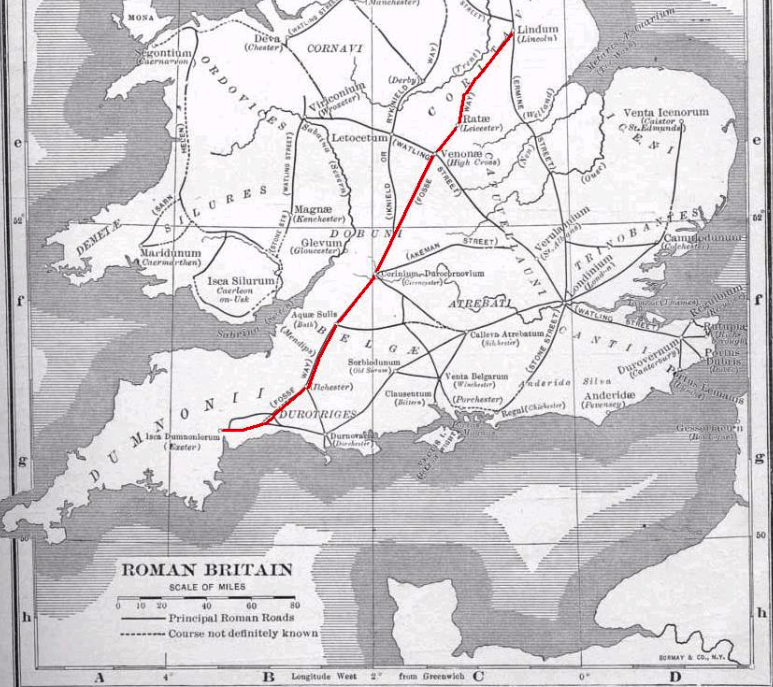

Lindinis, as it was known during the Roman period, was located just a few miles from South Cadbury Castle, and Glastonbury, Somerset. This fifty acre settlement lies where the Dorchester road interests with the Fosse Way, one of the major roads of Roman Britain.

During the Roman period, Somerset was an agriculturally rich area of the Empire, with many villa estates, such as that of Pitney (which also features in the story). These estates’ primary business was in crops such as spelt wheat, oats, barley and rye. The also raised livestock, mainly cattle, but also sheep, horses, goats, and pigs.

These Roman villa owners were wealthy, and Lindinis was one of the main markets where they brought their crops and livestock.

Lindinis was not always a Roman settlement, however.

It was originally a Celtic oppidum, a native center that consisted of a large enclosure with homes, food stores and livestock. One imagines Celtic Somerset as a place of peace and vitality.

But, in A.D. 43 the Romans arrived with the advent of the Claudian invasion of Britain. Forty-five thousand troops marched over the land, including four legions, and the native Britons fought, and lost. Vespasian, the future emperor, stormed the southern hillforts of Britain, including South Cadbury Castle, ushering in an age of Roman domination.

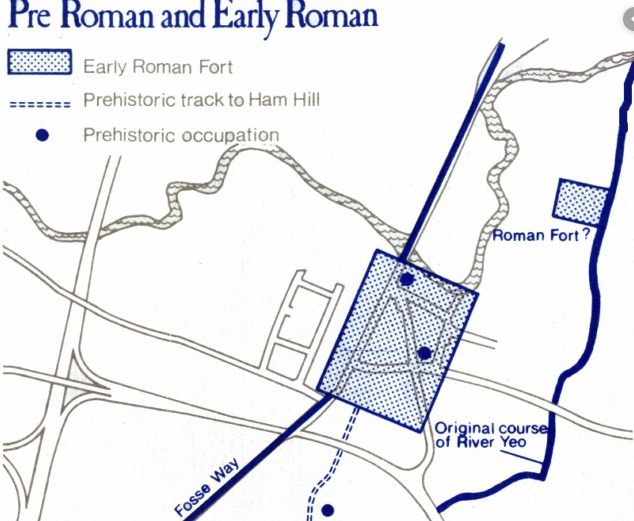

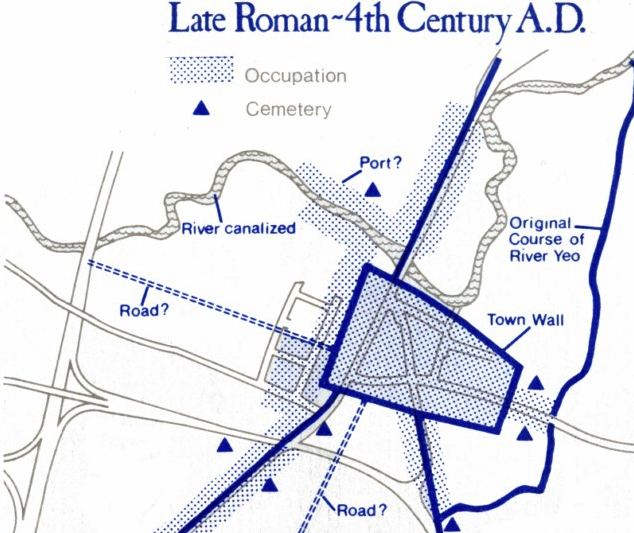

Eventually, at Lindinis, two successive forts were built on the site to the south of the river: one from Nero’s reign, and another during the Flavian period. There is also evidence for a third fort to the northeast of the river crossing where a double ditch enclosure has been discovered.

The Roman invasion of Britain was a violent time, and that violence carried on through the Boudiccan revolt of A.D. 59. But when the blood stopped flowing, an age of Pax Romana settled on the southwest of Britannia, and Lindinis was at the heart of it.

Lindinis, however, was not the main settlement of Roman Somerset. To maintain peace and order, and keep the economy running, the Romans instituted various civitates, centres of local government in which tribal groups of the region participated.

The council of a civitas was known as an ordo, and the members of the ordo were decurions, overseen by an executive, elected curia of two men. The ordo of a civitas usually included Romans, tribal aristocrats or local chieftains, and it was their job to administer local justice, put on public shows, see to religious taxation, the census, and represent the civitas in Londinium. Supreme authority, however, belonged to the Provincial Governor who was aided by a procurator, the ‘tax man’.

There were three major civitates during the Roman period in southwestern Britannia: Durnovaria (modern Dorchester) the civitas of the Durotriges tribe, Isca Dumnoniorum (modern Exeter) the civitas of the Dumnonii, and to the north Corinium Dobunnorum (modern Cirencester) the tribal centre of the Dobunni.

Despite its large market and location at a crossroads along the artery of the Fosse Way over the river Yoe – in the southwest, the Fosse Way ran from Isca Dumnoniorum (modern Exeter) to Aquae Sulis (modern Bath) – Lindinis was not one of the major civitates of the region, though it did rival nearby Durnovaria.

In addition to a thriving market where wine, oil, clothing, ornaments, jewellery, tools, pottery and glass were sold, Lindinis also had gravel and stone streets, and stone walls (later). People also came to Lindinis to pay their taxes.

Where the road diverges in Ilchester – the left to Exeter, the right to Dorchester. See the bridge over the river directly ahead.

There was also a small garrison.

Lindinis may have seen itself as the civitas Durotrigum Lendiniensium, but it could not be an official civitas as one of the requirements for civitas status was a basilica or forum. Lindinis did not have either of those.

Roman Lindinis had a large role to play in the economy of Roman Somerset, but perhaps not as large as its ordo would have liked. It also found itself in difficult situations during its time, for during the civil war (A.D. 193) between Septimius Severus, Pescennius Niger, and Clodius Albinus, Lindinis was forced to declare for Clodius Albinus who was in Britannia when he made his claim. At this time, new defences were built around Lindinis, as if in anticipation of the trouble to come.

In the book, Isle of the Blessed, Lucius Metellus Anguis, the main protagonist in the Eagles and Dragons series, has several run-ins with the ordo members of Lindinis’ ruling council who see him as a person of influence at the imperial court, a man who could help their small town to become much more.

Historically, despite its lack of a proper forum or basilica, it seems that Lindinis did succeed in attaining a measure of civitas status, for along Hadrian’s Wall, two inscriptions have been found bearing the name of a detachment from the ‘Civitas Durotragum Lendiniensis’, or the ‘Lindinis tribe of the Durotriges’.

This, despite the presence of the other three, official civitas settlements Durnovaria, Isca, and Corinium.

Who knows? Perhaps the persuasiveness of the ordo members of Lindinis, the settlement’s important location, and the size of its market helped to sway the Roman authorities to grant civitas status.

In Isle of the Blessed, we see how far the local politicians are willing to go.

I hope you’ve enjoyed part two of The World of Isle of the Blessed.

Next week, in Part III, we will look at the history, myth and legend surrounding what is known in Isle of the Blessed as Ynis Wytrin, that is, Glastonbury, England.

Thank you for reading.

Isle of the Blessed is now available in e-book and paperback from all major on-line retailers. If you haven’t read any books in the Eagles and Dragons series yet, you can start with the #1 bestselling A Dragon among the Eagles for just 0.99! Or get the first prequel novel, The Dragon: Genesis, for FREE by clicking HERE.

The World of Isle of the Blessed – Part I – The Dragon’s Domus

Salvete, readers and history-lovers!

Welcome to The World of Isle of the Blessed!

In this seven-part blog series, we’re going to be taking a look at the research that went into my latest historical fantasy release, Isle of the Blessed, Book IV in the #1 bestselling Eagles and Dragons series.

Over the next few weeks, I’ll take you on a journey through the world of early third-century Roman Britain in which we will look at the history, archaeology, and historical events that took place during this pivotal time in the Roman Empire in which the book is set.

In this first post, we’re taking a closer look at a site that is well-known to Arthurian enthusiasts: the hillfort of South Cadbury Castle.

At the very south ende of the chirche of South-Cadbyri standith Camallate, sumtyme a famose toun or castelle… The people can tell nothing ther but that they have hard say that Arture much resorted to Camallate. (John Leland, Royal Antiquary, 1532)

The hillfort of South Cadbury Castle in Somerset, England, is one of the major locations in Isle of the Blessed. However, most people are familiar with it as a site with strong Arthurian associations. As such, its importance and role is hotly debated.

Though Isle of the Blessed is not a story of King Arthur and the Knights of the Round Table, it is difficult not to speak of this important Iron Age site without discussing the Arthurian connection.

Was South Cadbury Castle the power centre of the historical Romano-British warlord, or dux bellorum, we know as ‘King Arthur’? Was this the actual site of what has come to be known in the popular imagination as ‘Camelot’?

I’ve always been a strong proponent of the theory that there was in fact, an historical ‘Arthur’ who formed the factual basis for all the legends we love and cherish. So, when I look at sites such as South Cadbury, I do so with that in mind. However, that doesn’t mean that I accept a site’s association with Arthur on faith alone.

I know this site pretty well – as I studied it and wrote about it as part of my Master’s dissertation entitled “Camelot: A look at the historical, archaeological, and toponymic evidence for King Arthur’s Capital”. As part of this, I looked at three of the main candidates for Camelot that had been put forward at the time – Wroxeter (Roman Viroconium), Roxburgh Castle (in the Scottish Borders), and South Cadbury. There is a copy of the dissertation hidden somewhere in the stacks at the St. Andrews University library in Scotland.

South Cadbury Castle is also where I cut my teeth as an archaeologist as part of the South Cadbury Environs Project team for a couple of seasons under the leadership of Richard Tabor. This was a wonderful experience that helped me to get up close and personal with the site I had studied for so long – I dug test pits, got into bigger trenches in which curious cows came to watch what I was doing, carried out geophysical surveys with a magnetometer, and found some curious objects such as a bronze dolphin that formed the handle of a Roman drinking cup.

Most of all, I was given the chance to spend more time on this amazing, and yes, magical, landscape.

And a couple years ago, when doing research for Isle of the Blessed, I returned to South Cadbury where I also filmed a mini-documentary on the site (coming out later this year!).

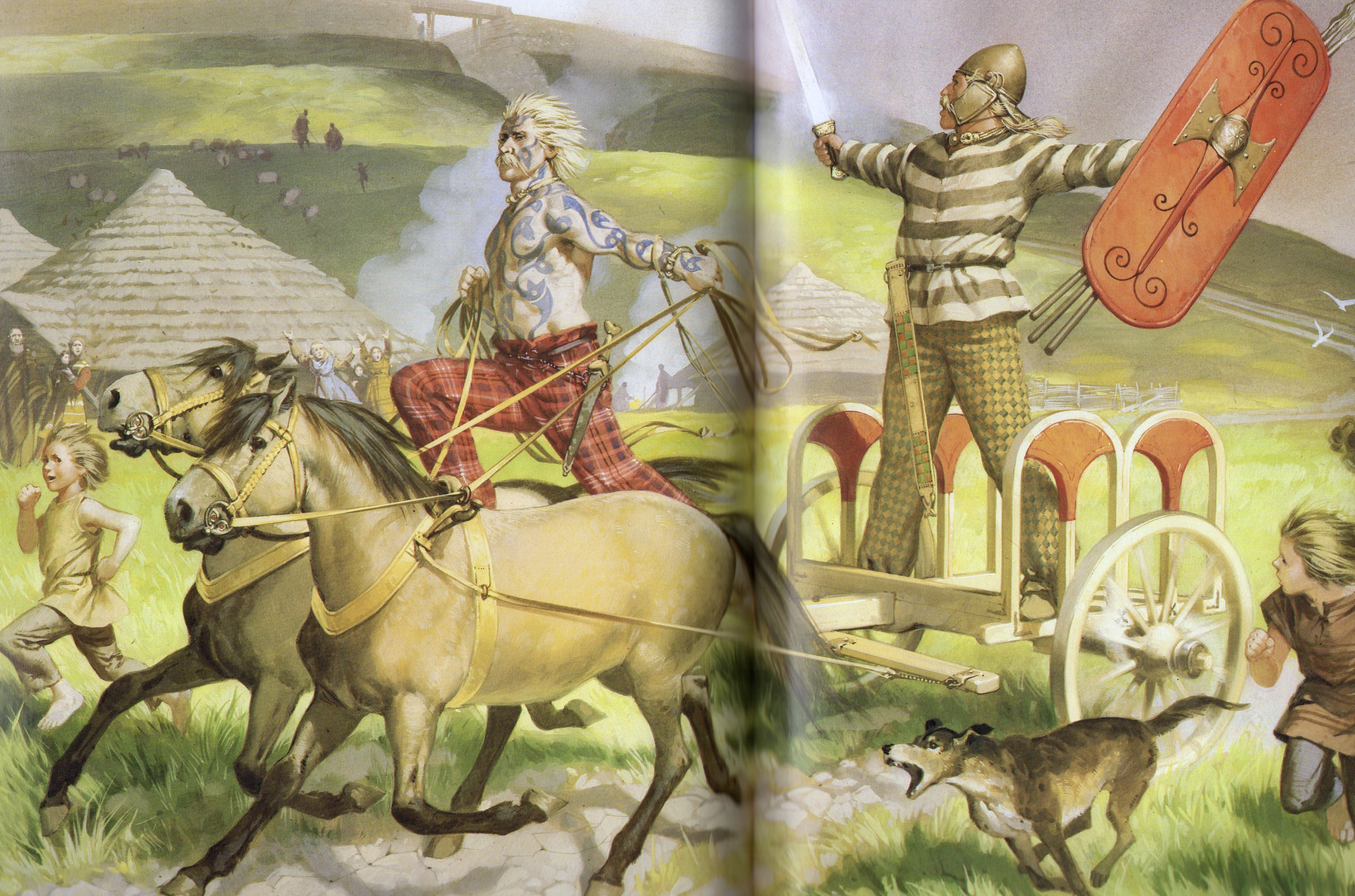

British Belgic Warriors of the Iron Age – Illustrated by Angus McBride (source – Rome’s Enemies 2 – Gallic and British Celts)

Before I give my thoughts on wandering the slopes of South Cadbury Castle, we should have a look at what it actually is.

South Cadbury Castle is not the late medieval castle with banners flying from tall towers that make up our usual image of Camelot. It is a 500 foot high Iron Age hillfort located in the pre-Roman era lands of the Durotriges. Occupation of the site began in the Neolithic period and it went through various stages of occupation from the 5th century B.C. onward.

By the time of the Roman invasion of Britain, it had four massive defensive ramparts with an inner area of about 18 acres. Access to the top was by two entrances, one to the north-east and the other, larger one, to the south-west. The Iron Age occupation of the site came to a violent end around A.D. 43 when Vespasian stormed the southern hillforts of Britannia.

The Romans made little use of the site, though there have been some theories that it was used as a Roman supply station. This theory is explored in Isle of the Blessed and the Eagles and Dragons series. In the 3rd and 4th centuries, there was renewed activity with visits being made to a Romano-Celtic temple that was built on the site.

Location of the Romano-British temple in the south-east sector of the hillfort of South Cadbury Castle

During excavations, a bronze letter ‘A’ was found that some believe belonged to this temple, which was perhaps dedicated to Mars, or some other deity.

However, when it comes to South Cadbury Castle, the periods that have always drawn me to it are the 5th and 6th centuries A.D. This period of the site is known as the ‘Arthurian’ period, and it is at this time, after Rome’s legions had left the island, that the archaeology shows a massive refortification of the hillfort.

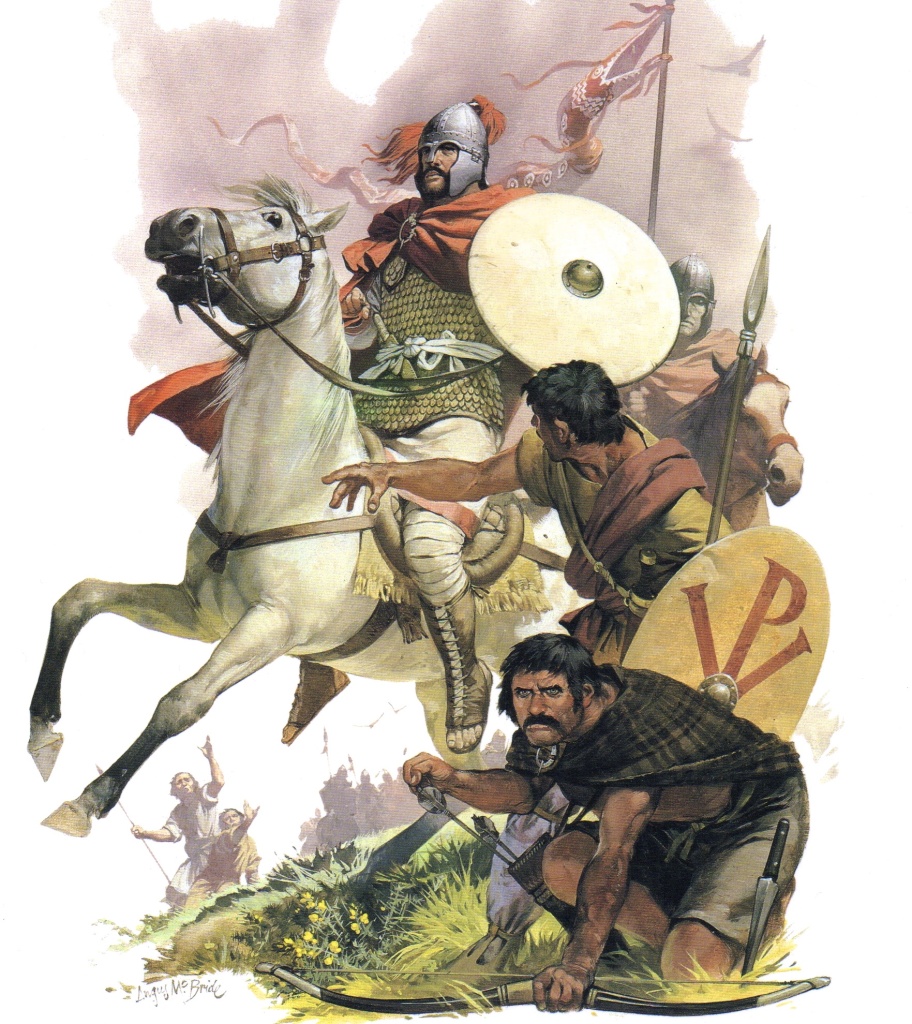

6th Century British Warriors – Illustrated by Agnus McBride (source – Arthur and the Anglo-Saxon Wars)

Though it is much debated, South Cadbury’s association with the Arthurian period stems not just from hearsay and folklore. It has the archaeological evidence to back it up.

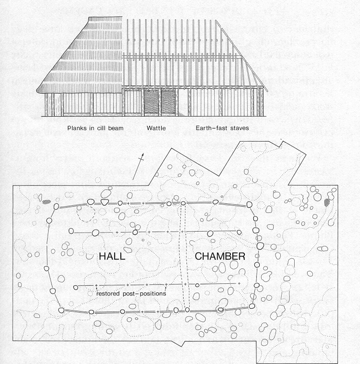

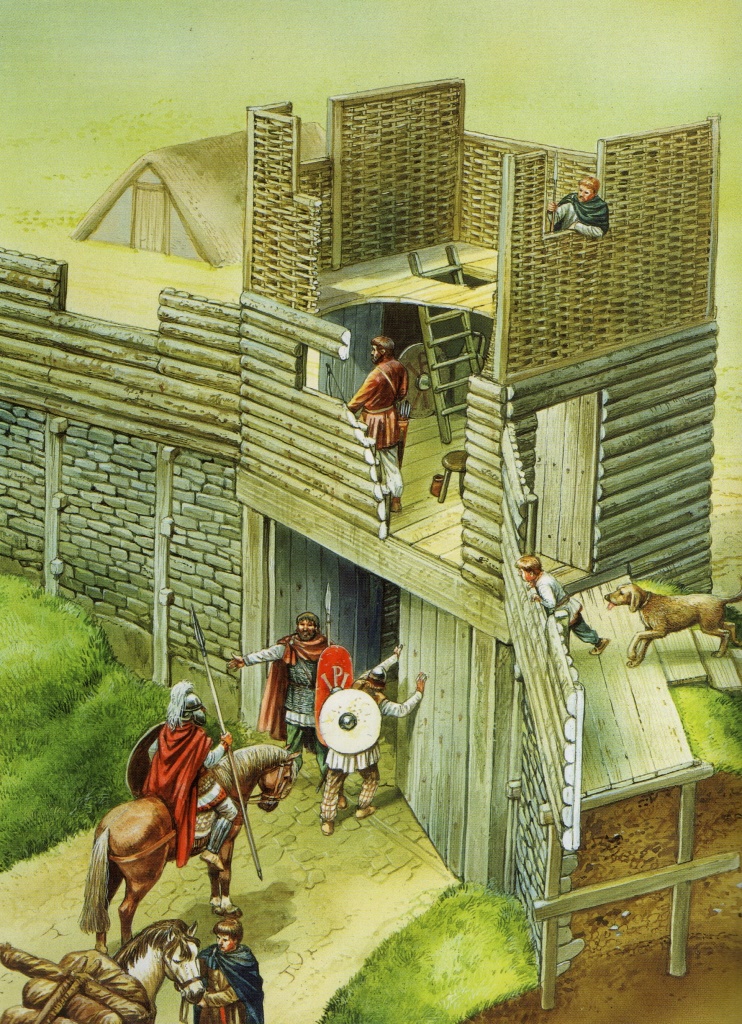

There have been a few big excavations of the hillfort over the years, but the biggest of all took place in the late 1960s and was headed by Professor Leslie Alcock. Professor Alcock and his team discovered evidence for a large scale occupation and refortification of the hillfort, during the Arthurian period, which showed repaired defences, including a strong gatehouse at the south-west entrance, and most importantly, several buildings, including a kitchen and a large timber hall on the fort’s high plateau.

The discovery of post holes reveals a finely-built timber hall that was on a large scale, measuring about 63×34 feet. This hall would not have been the great castle hall of late medieval romance, but rather something like the timber drinking halls of the period, more like to the Golden Hall of Meduseld, the seat of King Theoden in Lord of the Rings.

Another very telling discovery at Cadbury Castle was the large quantity of Mediterranean pottery that dates to the Arthurian period of activity. This is the same pottery type that was discovered at Tintagel Castle in Cornwall, a site that also has strong Arthurian associations. One might think that shards of pottery from wine, olives and olive oil might be pretty mundane, but they anchor the sites strongly in the period, and also show that someone of importance was associated with the site. Not everyone could afford to import such things through trade.

The refortification of the hillfort during the Arthurian period was on a massive scale, and would have required many resources and men to hold it. South Cadbury castle was, in a way, on the front lines of the British struggle against the invading Saxons, and would have been well-placed to meet the Saxons as they advanced westward.

Based on the refortification, and evidence of the gatehouse that linked the ramparts running over the cobbled road at the south-west corner, this place was likely the base for an army that was large by the standards of the period. It may have been the site of the court of the dux bellorum, or the historical Arthur.

Artist Reconstruction of the South-west gate – Illustrated by Peter Dennis (Source – British Forts in the Age of Arthur)

I am only scratching the surface here, as far as the archaeological finds. For a more academic look at South Cadbury Castle, you will want to read the upcoming Historia series release Camelot: The Historical, Archaeological and Toponymic Considerations for South Cadbury Castle as King Arthur’s Capital. (Make sure you are signed-up to the mailing list be notified of that release)

South Cadbury Castle was finally abandoned in the early 11th century when it was being used as a royal mint during the reign of the Saxon king, Aethelred.

Today, South Cadbury Castle is a quiet hill in the midst of the Somerset countryside where it lies just south of the A303 motorway. The levels of its steep ring fortifications are now overgrown with trees and scrub, and cows roam the fields surrounding it.

When you visit, you pull your car into the small car park at the south end of the village of South Cadbury, just east of the hillfort. From the lane, you can’t really tell what you’re looking at. It seems like a steep, forested hill with a path leading up.

This path leads up to the north-east gate of the hillfort, and for me, it was always the gateway to another time, another realm.

It’s difficult to approach this site and reconcile the archaeologist/historian side of me with the romantic. Arthurian lore runs deep in my veins, and has had a hold on my psyche since I was very young. The first time I visited the site, I could almost hear the call of clear trumpets and the thumping of horses’ hooves upon the ground as knights returned home from their adventures, their horses brightly caparisoned, their armour shining brightly in the light of the Summer Country.

Of course, I know that is not how it was during the Arthurian period, but this is a place and story that fires the imagination. Cadbury Castle’s associations with Arthur include a hollow hill where he sleeps until he is needed again, the site of ‘Arthur’s Well’, a place on the slopes where his horse drank when he led the Wild Hunt, and of course the location of Camelot.

To me, however, the idea of South Cadbury as the main fortress of a Romano-British warlord leading a group of skilled cavalry in a last stand against the invading Saxons is no less romantic.

During my subsequent visits, I would ascend the dirt and rock path leading up to the northeast gate and pause with reverence for the history of the place. I would imagine looking ahead, up the slope to the central plateau of the hillfort to the great wooden hall where smoke from the hearth of Arthur’s hall wafted into the sky as he and his warriors discussed the fight for their lives and their Romano-British heritage.

The warriors that manned the ramparts of South Cadbury, who dined in the hall, and who rode out to meet the Saxons, have been wrapped in the fabric of myth, as much as the Isle of Avalon not ten miles distant, in Glastonbury. But they certainly left a mark on the place, on history and folklore.

As I walk the grass-covered ramparts of South Cadbury, watching the crows dive in the winds above the steep slopes, I can’t help but wonder if Arthur, Gawain, Bors, Tristan, Bedwyr, Cai and others walked that same path, a wary eye out for a sign of the enemy that would shatter the peace they had fought so hard for at the famed battle of Mons Badonicus.

Rarely have I felt so at peace and nostalgic as I have when walking around this hillfort. I can still smell the damp grass and feel the sun on my face. In my mind, I still watch the puffs of white cloud blowing over the Somerset landscape as I pause to gaze to the north-west and see Glastonbury Tor rising out of the earth.

In ages past, when the levels flooded, the distance between Cadbury Castle and Glastonbury might have been crossed by boat if you knew the way and which rivers to take. Indeed, one of the discoveries found around the hillfort was a boat.

South Cadbury Castle is, in some ways, closely tied to Avalon, and you can feel that as you look from the top of one to the other. This too is explored in Isle of the Blessed.

After making a round of the ramparts, and standing on the roadway of the south-west gate, I would always spend a good amount of time on the plateau, watching the sky and letting my imagination take hold.

The beauty of visiting a site, rather than looking at in a book or online, is that direct connection with the past, with the history of the place.

Yes, many of the stories we know and love about Arthur and the Knights of the Round Table are medieval fabrications. But I do believe that every legend has its base in fact, and so it’s a comfort to know that the layers of myth and legend are veined with elements of possible truth and history.

Many people will disagree, and that’s ok. When it comes to Arthur we will never reach a consensus.

However, considering the archaeological evidence at South Cadbury Castle, along with its location and the apparent activity during the Arthurian period, it seems quite possible that if there was an historical Arthur, he would undoubtedly have been familiar with this magnificent hillfort.

Was this just another strong point in the British defensive network? Or was it the Arthurian power centre that has come to be known as Camelot?

Whatever the answer is, it is surely fascinating, and perhaps unattainable. But then, that is what makes these historical mysteries so intriguing.

If you ever manage to roam the lands In Insula Avalonia, just be sure to make your way to South Cadbury Castle. Walk up the steep slopes, and through the gate, and know that you may just be walking in the footsteps of Arthur.

I hope you’ve enjoyed this first part of The World of Isle of the Blessed.

Be sure to tune in for Part II in which we will look the history of another setting in Isle of the Blessed: the village of Ilchester, Roman Lindinis.

Thank you for reading.

Isle of the Blessed is now available in e-book and paperback from all major on-line retailers. If you haven’t read any books in the Eagles and Dragons series yet, you can start with the #1 bestselling A Dragon among the Eagles for just 0.99! Or get the first prequel novel, The Dragon: Genesis, for free by signing-up for the newsletter HERE.

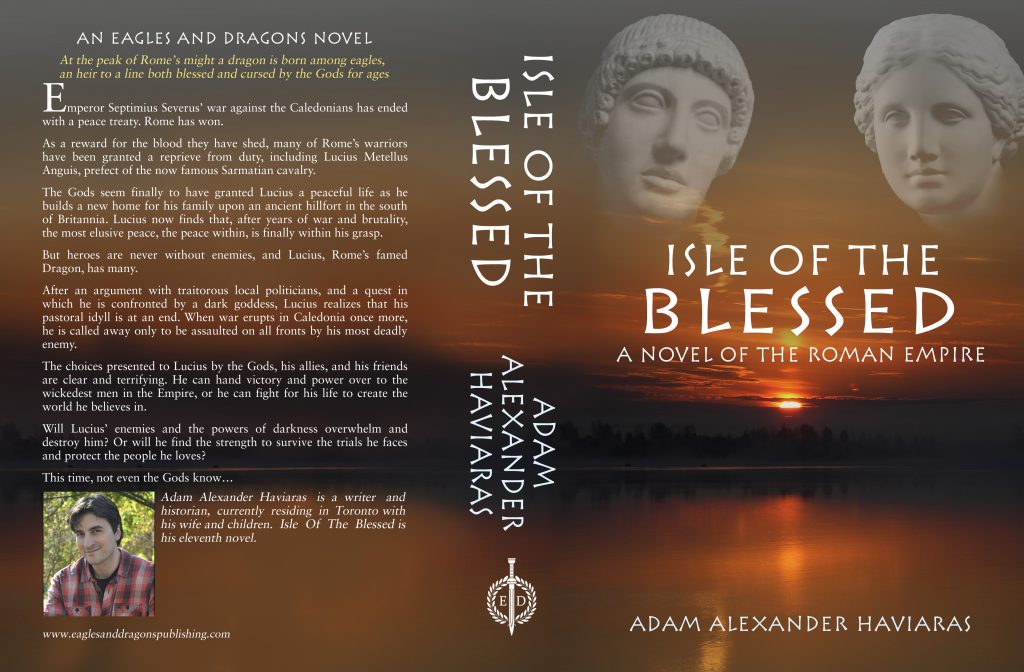

A New Eagles and Dragons Series Novel!

We’re excited to announce the official launch of Isle of the Blessed, Book IV in the #1 bestselling Eagles and Dragons historical fantasy series.

Fans of this series have been waiting quite a long time for this book, but now the wait is over.

Sound the cornu and slam your gladii against your scuta!

Isle of the Blessed – Eagles and Dragons Book IV

At the peak of Rome’s might, a dragon is born among eagles, an heir to a line both blessed and cursed by the Gods for ages.

Emperor Septimius Severus’ war against the Caledonians has ended with a peace treaty. Rome has won.

As a reward for the blood they have shed, many of Rome’s warriors have been granted a reprieve from duty, including Lucius Metellus Anguis, prefect of the now famous Sarmatian cavalry.

The Gods seem finally to have granted Lucius a peaceful life as he builds a new home for his family upon an ancient hillfort in the south of Britannia. Lucius now finds that, after years of war and brutality, the most elusive peace, the peace within, is finally within his grasp.

But heroes are never without enemies, and Lucius, Rome’s famed Dragon, has many.

After an argument with traitorous local politicians, and a quest in which he is confronted by a dark goddess, Lucius realizes that his pastoral idyll is at an end. When war erupts in Caledonia once more, he is called away only to be assaulted on all fronts by his most deadly enemy.

The choices presented to Lucius by the Gods, his allies, and his friends are clear and terrifying. He can hand victory and power over to the wickedest men in the Empire, or he can fight for his life to create the world he believes in.

Will Lucius’ enemies and the powers of darkness overwhelm and destroy him? Or will he find the strength to survive the trials he faces and protect the people he loves?

This time, not even the Gods know…

We hope you like the sound of this one. It promises to take you on an adventure in the Roman Empire that you won’t forget, and the editorial team and beta readers have told us that this is Adam’s best book to date!

You can learn more and find all the links to get your copy ON THIS WEB PAGE.

Isle of the Blessed is available in e-book format at all major on-line retailers, and currently in paperback from Amazon.

If you haven’t read any books in the Eagles and Dragons series, you can start the series for FREE with the full-length novel, The Dragon: Genesis, which you can download by CLICKING HERE.

Here’s to a new adventure in the Roman Empire!

Happy Reading!

The World of Warriors of Epona – Part V – Legions in the North: The Romans in Scotland

Warriors of Epona is set against the backdrop of the Severan invasion of Caledonia (modern Scotland). It was a massive campaign, and Rome’s last major attempt at subduing the tribes north of the Antonine Wall.

However, this was not the first time Rome had attempted to invade Caledonia. In fact, Septimius Severus’ legions were using the infrastructure of previous campaigns into this wild, northern frontier.

In this fifth and final part of The World of Warriors of Epona, we’re going to look briefly at the Roman actions in Caledonia prior to and including the campaigns of Emperor Septimius Severus.

The full scale conquest of Britannia was undertaken in A.D. 43 under Emperor Claudius, with General Aulus Plautius leading the legions. Campaigns against the British tribes continued under Claudius’ successor, Nero in A.D. 68.

The conquest of the South of Britain involved overcoming the tribes, including Boudicca and the Iceni, the Catuvellauni, the Durotriges, the Brigantes, and others, and the attempted extermination of the Druids on the Isle of Anglesey.

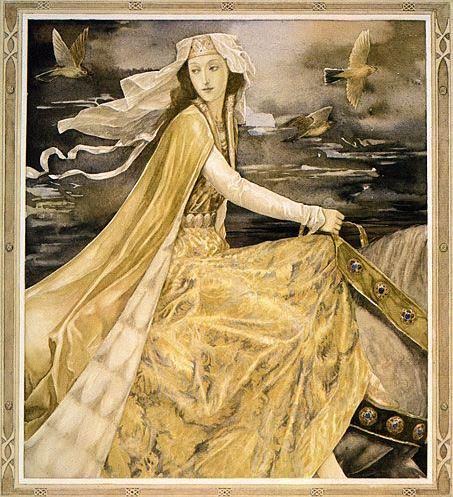

Boudicca

Eventually, after much blood and slaughter, the South was subdued, and the Pax Romana began to take root in that part of Britannia. (It pains me to gloss over so large a part of the history of Roman Britain, but we’re talking about Caledonia here…)

It was not until A.D. 71 that Rome decided it was time to invade Caledonia, and the man assigned this task was Quintus Petillius Cerialis, a veteran of the Boudiccan Revolt, and governor of Britannia at that time.

Once Cerialis’ legions were able to break through the Brigantes, it was time to press north into Caledonia.

The person who is most associated with these initial campaigns in Caledonia is none other than Gnaeus Julius Agricola, who had served in the campaigns against Boudicca in the South and who was also governor of Britannia from A.D. 77-85.

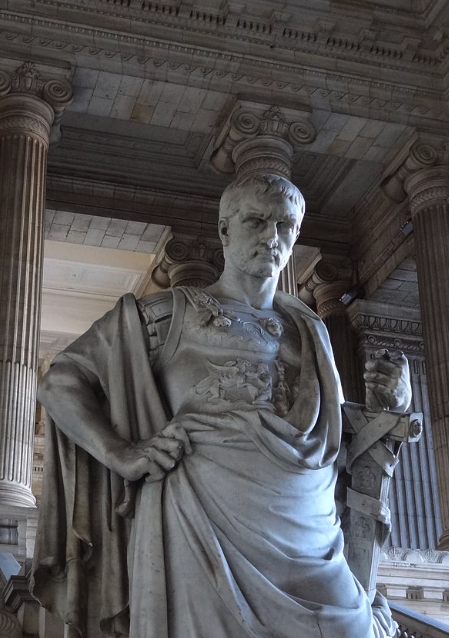

Agricola – Statue at Roman Baths, Bath, England

In around A.D. 80, Emperor Titus (A.D.79-81) ordered Governor Agricola to begin the campaigns into Caledonia by consolidating all of the lands south of the Forth-Clyde (roughly between Edinburgh and Glasgow). This involved taking on the tribes of the Borders, including the Selgovae, Maeatae, Novantae, and Damnonii.

It is in during this campaign that the fort at Trimontium, and many others were established in the Borders.

Commemorative stone at Newstead, in the Scottish Borders

By A.D. 81, Emperor Domitian had decided to order Agricola and his legions into Caledonia, and within two years, Agricola is said to have brought the Caledonians to their knees at the Battle of Mons Graupius.

He [Agricola] sent his fleet ahead to plunder at various points and thus spread uncertainty and terror, and, with an army marching light, which he had reinforced with the bravest of the Britons and those whose loyalty had been proved during a long peace, reached the Graupian Mountain, which he found occupied by the enemy. The Britons were, in fact, undaunted by the loss of the previous battle, and welcomed the choice between revenge and enslavement. They had realized at last that common action was needed to meet the common danger, and had sent round embassies and drawn up treaties to rally the full force of all their states. (Tacitus, Agricola; XXIX)

The Roman historian, Tacitus, was actually Agricola’s son-in-law, and his account, De vita et moribus Iulii Agricolae, provides us with the best first-hand account of Agricola and his invasion of Caledonia.

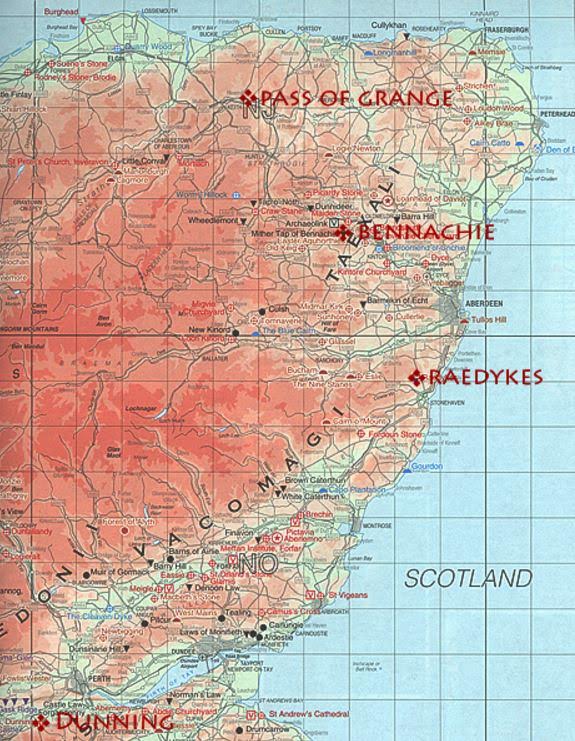

Possible locations for Battle of Mons Graupius

This is a time of legions exploring the unknown reaches of the Empire.

Sadly, the battlefield for Mons Graupius has not been identified, though there are certain candidates.

What is fortunate, however, is that Agricola’s legions left a long train of breadcrumbs in the form of marching camps, legionary bases, watch towers and of course, roads, all the way to northern Scotland.

And it is network of war that was to be used in later invasions of Caledonia.

Early Roman campaigns in Caledonia

War broke out again on the Danube frontier at this time, and so Roman man-power was sucked out of Britannia and Caledonia to meet threats elsewhere in the Empire.

And so, the legions in Caledonia went into a period of retrenchment and pulled back to the Forth-Clyde by A.D. 87.

By the time of Emperor Trajan’s reign, c. A.D. 99, Rome had retreated farther to the South to the Tyne-Solway, the future line of Hadrian’s Wall, construction of which began in A.D. 122.

The Caledonian lands for which Agricola and his legions had fought, had been given up for the time being.

Hadrian’s Wall

As was the case for centuries to come, the lands between the Forth-Clyde line, and the Tyne-Solway line, the area known today as the Scottish Borders, went into a period of push and pull, of occupation, retreat, and re-occupation.

It was during the reign of Antoninus Pius (A.D. 138-161) that it was deemed necessary to re-occupy the lands lost during the Flavian period, and so the army advanced again across the borders, using those same roads and forts that had been constructed by Agricola, and constructing new ones.

Twenty years after construction began on Hadrian’s Wall, Antoninus Pius ordered the construction of a new wall in Caledonia itelf in A.D. 142. This was the Antonine Wall, and it’s earth and timber ramparts ran the width of Caledonia from the Forth to the Clyde in an attempt to hem the raucous tribes in on their highlands.

The Antonine Wall

But, after more campaigning and entrenchment by Rome, the Antonine Wall was abandoned during the reign of Marcus Aurelius in around A.D. 163.

A few outposts remained in use to the north of Hadrian’s Wall, but for the most part, the bones of the Empire were left to rot and be overwhelmed by the Caledonians and their allies.

For the next forty years, the northern tribes became a menace, breaking through the frontier defences twice, once during the reign of Commodus (c. A.D. 184) and then again during the early part of Septimius Severus’ reign in A.D. 197.

Septimius Severus

When Septimius Severus took the imperial throne, he was immediately engaged in consolidating the Empire after the civil war, and then taking on the Parthian Empire. He was a military emperor, and he knew how to keep his troops busy, and how to reward them.

The Caledonians had been a thorn in Rome’s side for a long while at that time, but it was not until A.D. 208 that Severus was finally able to deal with them. And so, the imperial army moved to northern Britannia, poised to take on the Caledonians once again.

We’ve already touched on Severus’ campaign in previous parts of this blog series. However, it’s important to note that this is believed to be the last real attempt by Rome to take a full army into the heart of barbarian territory.

Severus moved on the Caledonians with the greatest land force in the history of Roman Britain, making use of his predecessors’ fortifications (such as the Gask Ridge frontier) and roads, and penetrating almost as far as Agricola’s legions over a hundred years before.

According to Cassius Dio, when the inhabitants of the island revolted a second time, Severus:

…summoned the soldiers and ordered them to invade the rebels’ country, killing everybody they met; and he quoted these words: ‘Let no one escape sheer destruction, No one our hands, not even the babe in the womb of the mother, If it be male; let it nevertheless not escape sheer destruction.

Rome was poised for a final push, and ultimate victory over the Caledonians.

Goddess Fortuna

But Fortuna was not on Severus’ side, for it was at that time that his chronic health problems finally got the better of him.

In A.D. 211, the man who had won a brutal civil war, and who had finally brought the Parthians to heel, died at Eburacum (modern York) in Britannia.

Roman Tower at Eburacum (York)

His son, Caracalla, who was ill-equipped to handle the situation, struck a deal with the Caledonians, abandoning all the headway his father had made in that northern land, and all of the blood shed by fifty-thousand Romans in the Severan campaign.

What happened after the death of Severus is for another story (i.e. for the next book!). However the Severan conquests in Caledonia did usher in a fleeting period of tranquility.

Later expeditions into the North were mounted in c. A.D. 296 by Constantius Chlorus, and by his son, the future Emperor Constantine, in A.D. 306. However, neither of these campaigns were on a scale comparable to the Severan campaign.

Like other remote corners of the Empire, Caledonia must have seemed like a lost cause.

Roman Cavalry

But the Eagles and Dragons series is not yet finished with this exciting period of history in Roman Britain. Like Severus, we are poised for a final punitive push into the Highlands.

It’s a fascinating period in Roman history, and I hope you have enjoyed this journey through The World of Warriors of Epona with me. If you missed any of the previous blog posts in this series, you can read them all on one page by CLICKING HERE.

If you would like to learn a bit more about the Romans in Scotland, I highly recommend checking out the documentary Scotland: Rome’s Final Frontier with Dr. Fraser Hunter.

Warriors of Epona is out now on Amazon, Apple iBooks/iTunes, and Kobo, so be sure to get your copy today.

Remember, if you haven’t yet read any of the Eagles and Dragons novels, and if you want to get stuck in, you can start with the #1 Best Selling prequel novel, A Dragon among the Eagles. It’s a FREE DOWNLOAD on Amazon, Apple iTunes/iBooks, and Kobo.

Thank you for reading!

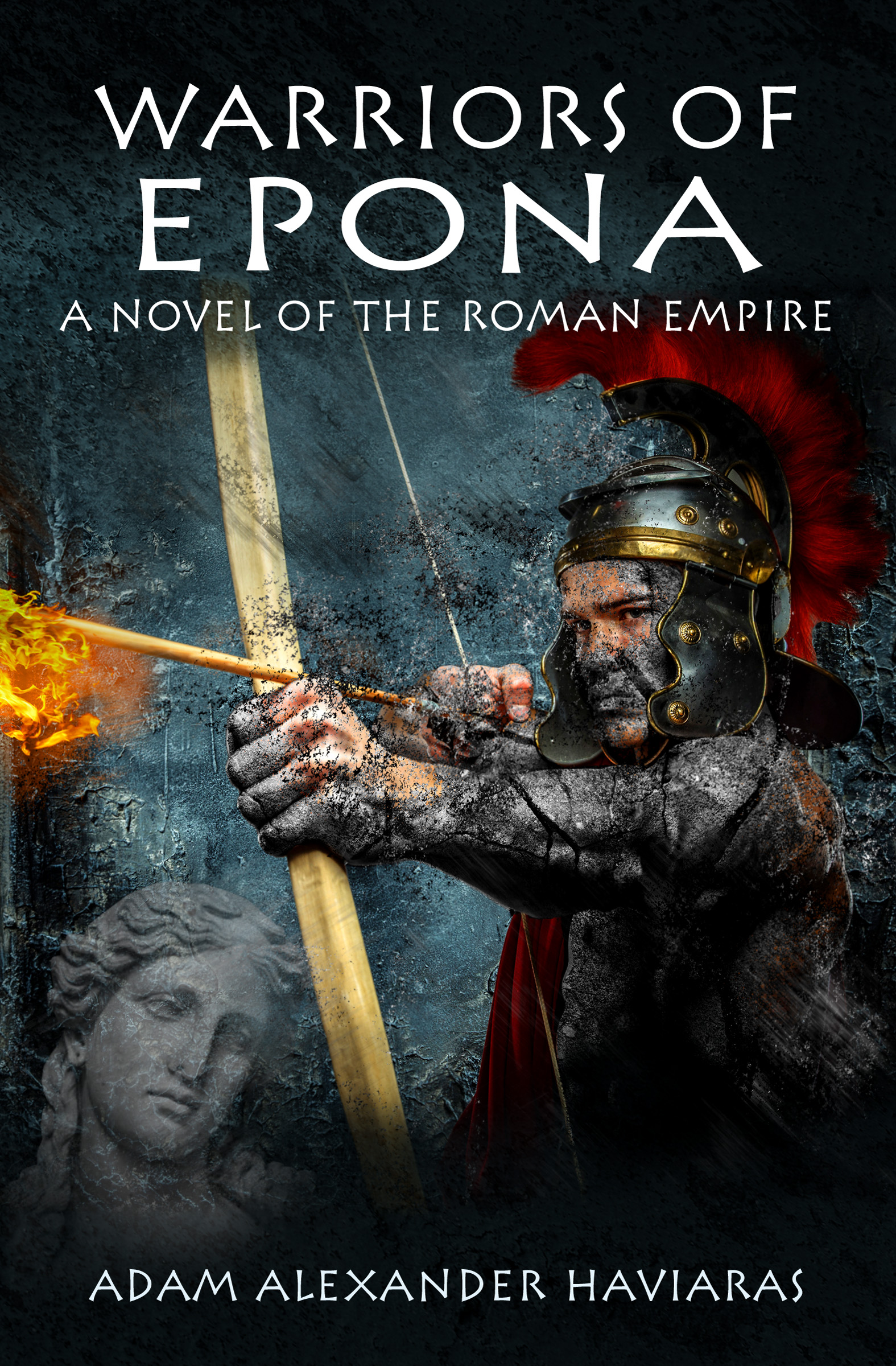

The World of Warriors of Epona – Part I – Epona: Goddess of Horses

The Eagles and Dragons saga is marching on, and so I’m very excited to begin a new series of blogs posts based on the newest release, Warriors of Epona.

Writing the Eagles and Dragons series has been a fantastic and exciting adventure thus far, for me and for the characters inhabiting this world. And with each new book, I’ve tried to explore new realms, new areas of thought and belief, and to plumb new depths of the human experience.

In Warriors of Epona Lucius Metellus Anguis’ journey leads him down a very different path to a place that is both beautiful and terrifying.

I do hope that you enjoy the next phase in this adventure.

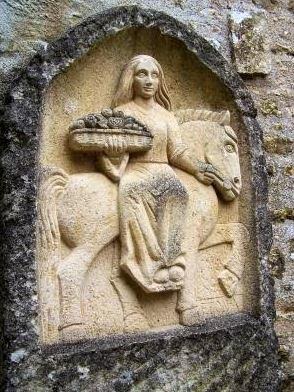

Epona and horses (Wikimedia Commons)

In Part I of The World of Warriors of Epona, I want to introduce you to a new character in the series, a goddess.

In Warriors of Epona Lucius has started the next phase of his military career as the praefectus of a Sarmatian cavalry ala. To read more about the Sarmatians, CLICK HERE.

Originally, Epona was a Celtic horse goddess, and some believe that her worship spread out from Alesia, in Gaul, at the time of Caesar’s conflict there with the Celtic war leader, Vercingetorix.

The interesting thing about Epona is that she came to be widely worshiped by Romans as well. This was a truly unique circumstance for a Celtic goddess, for worship of such deities was usually local in nature, and then they were often combined with a Roman god (for example the worship of Sulis Minerva at Bath).

Epona riding side saddle

However, the worship of Epona spread across the Roman Empire, especially among cavalrymen, and dedicatory inscriptions and altars to her have been found largely along the Rhine and Danube frontiers, but also in Gaul and Britannia.

She was also associated with plenty, and some of the few representations that survive show her holding sheaves of wheat. She was also associated with apples.

The Roman festival of Epona was celebrated on December 18th.

I have always been drawn to Epona since I read the Mabinogion, the compilation of early Welsh tales, or ‘Triads’. In the tale Pwyll, Prince of Dyfed, the otherworldly woman, Rhiannon, is a reflection of the Goddess Epona, riding a brilliant white horse, followed by three white, red-eared hounds, and of course the birds of Rhiannon.

In Warriors of Epona, I chose to portray the goddess, who is Lucius’ new protector, as Rhiannon is portrayed in the Welsh Triads. If you have never read Pwyll, Prince of Dyfed, I highly recommend it as it beautifully portrays some of the strongest archetypes of ancient Celtic myth.

Here is an excerpt from Pwyll, Prince of Dyfed:

Once upon a time he [i.e. Pwyll] was in Arbeth, a chief court of his, with a feast laid out and great hosts of men all around him. After the first course, Pwyll got up to go for a walk and made for the top of a mound which was above the court and was called Gorsedd Arbeth.

‘Lord’, said one of the court ‘it is a peculiarity of the mound that whatever high-born man might sit upon it, he will not go away without one of two things: either wounds or blows, or his witnessing a marvel.’

‘I have no fear of wounds or blows in the midst of this host. A marvel, however, I would be glad to see. I will go,’ he continued ‘ and sit on this mound’. And he went to sit on the mound.

As they were seated, they could see a woman on a large stately pale-white horse, a garment of shining gold brocaded silk about her, making her way along the track which went past the mound. The horse had an even, leisurely pace; and she was drawing level with the mound it seemed to all those who were watching her.

‘Men’ said Pwyll ‘ is there any of you who recognizes that lady on horseback over there?’

‘There is not, my Lord,’ they replied.

‘One [of you] go up to her to find out who she is’ he said.

One [man] got up, but when he came onto the road to meet her, she had [already] gone past. He went after her as fast as he was able to on foot, but the greater was his speed, the further away from him she became. When he could see that following her was to no avail, he returned to Pwyll and said to him:

‘Lord, it is no use anyone in the world [trying] to follow her on foot.’

‘Aye,’ said Pwyll ‘go back to the court, and take the fastest horse that you know, and go after her.’

He took the horse and off he went. He got to smooth open country, and he began to set his spurs to the horse; but the more he struck the horse, the further away she became. Yet she still had the same pace with which she had begun. His horse flagged, and when he noticed his horse’s slackening pace, he returned to Pwyll.

‘Lord,’ said he ‘it is no use following that Lady over there. I haven’t known any horse in the land faster than this one, but [even on this] following her was to no avail.’

‘Aye’ said Pwyll ‘there is some kind of a magical meaning to this. Let us go [back] to the court.’

[So] they went [back] to the court, and passed the rest of that day. The next day they arose and that [too] passed until it was the hour to eat. After the first meal [Pwyll spoke thus]:

‘We will go – the company that we were yesterday – to the top of the mound. And you,’ he said to one his retainers ‘take with you the fastest horse you know in the field.’ And that the retainer did. They [then] made for the mound with the horse.

And, as they were sitting, they could see the woman on the same horse, with the same apparel about her, coming up the same road.

‘Look!’ said Pwyll ‘here comes the lady on horseback. Be ready, boy, to find out who she is.’

‘Lord, that I’ll do gladly.’

Thereupon, the lady on horseback drew level. The boy then mounted his horse, but before he had [even] settled in the saddle, she had already gone past, and there was a distance between them. Her pace was no different from the day before. He [too] put his pace at an amble, supposing as he did that however slowly his horse went, he might be able to overtake her. But it was no use. He loosed his at the reins, but got no nearer than if he had been on foot; and the more he beat his horse, the further away she became. [Yet] her pace was no greater than before. Since he saw it was useless [trying] to follow her, he returned, coming back to Pwyll.

‘Lord,’ said he ‘there is no more this horse can do than what you have seen.’

‘[So] I saw’ replied [Pwyll] ‘ its pointless anyone pursuing her. But between me and God,’ he continued ‘she has a message for someone on this plain, if obstinacy would [only] allow her to say it. Let us go back to the court.’

They came [back] to the court and spent the evening in song and carousel as they pleased.

The next morning, they passed the day until it was the hour to eat. When they had finished the meal Pwyll announced ‘Where is that group of us that went up on the mound yesterday and the day before?’

‘Here [we are], my Lord’ said they.

‘Let us go [then],’ said he ‘to sit upon the mound. And you’ he said to his stable-boy ‘saddle my horse well and bring him to the path, and bring my spurs with you.’ And that the boy did.

They came to sit on the mound. They had hardly been there any time before they caught sight of the lady on horseback, coming along the same path, with the same apparel, at the same pace.

‘Ah, boy, I can see the lady on horseback coming!’ said Pwyll ‘Bring me my horse.’

Pwyll mounted his horse, and no sooner than he had done so, she had passed him by. He turned after her, and let his lively horse prance at its own pace. He guessed that he would catch her up on the second or third bound. [But] no nearer did he get to her than [any of the times] before. He spurred on the horse as fast as it could go. But he saw it was useless following her [in this way].

Then Pwyll spoke: ‘Maiden,’ he said ‘for the sake of the man you love the best, wait for me!’

‘Gladly I’ll wait’ said she ‘but it might have been better for the horse if you had asked me a good while before.’

The maiden stopped and waited and drew aside the part of her headdress that was there to cover her face. She looked him in the eye, initiating conversation with him.

‘Lady,’ he asked ‘where are you from? And where are you going?’

‘Going about my business’ said she ‘and glad I am to see you.’

‘And you are also welcome to me,’ said he.

And he realized at that moment the faces of every woman and girl he had ever seen were dull in comparison to her face.

Rhiannon – Illustrated by Alan Lee