Greetings Readers, Hellenophiles, and Romanophiles!

Eagles and Dragons Publishing is proud to present an all new ‘World of’ blog series that will take a look at the research, people, and places related to the newest book in The Etrurian Players series, An Altar of Indignities: A Dramatic and Romantic Comedy of Ancient Rome and Athens.

We know that many of you are fans of these blog series connected with each of our book releases and we hope that you enjoy this one as much as those that have gone before.

In this newest series, we’ll be publishing a new article every two weeks or so on a wide range of relevant topics such as theatre, ancient Athens, festivals, religion, playwrights, customs and more.

And now, without further ado, let’s step into The World of An Altar of Indignities!

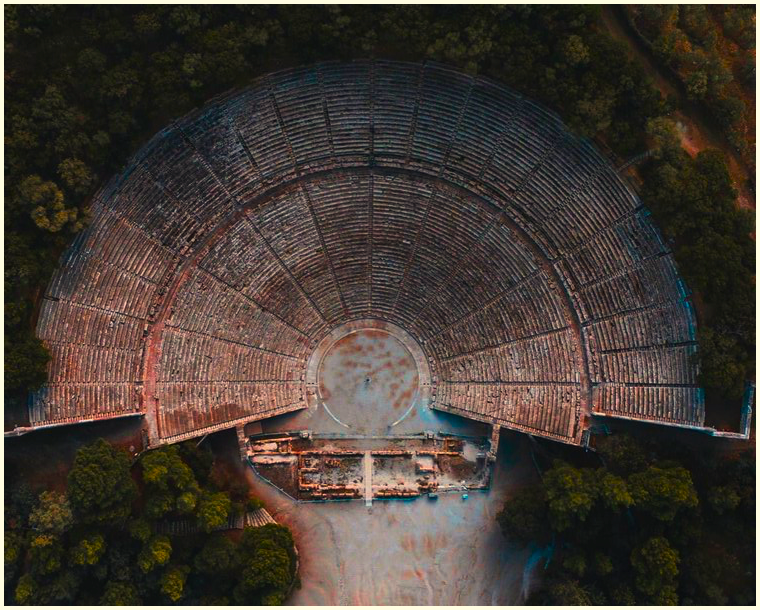

The Theatre of Epidaurus

In this first post, we’re going to be taking a brief look at drama and theatres in ancient Athens.

But this book is set during the Roman era, isn’t it? you might ask.

That is true, but the Romans were the inheritors and adopters of Greek theatrical traditions and, as the book is set in Roman Athens, we thought it would be good to start with a look at the birth of drama in ancient Greece.

Tragedy is an imitation of an action that is serious, complete, and of a certain magnitude…through pity and fear effecting the proper purgation of these emotions.

(Aristotle, Poetics)

In the West, we owe a great deal to the ancient Greeks, particularly the Athenians. Out of ancient Greece came epic poetry, and lyric poetry sung to music. There was elegiac poetry that expressed personal sentiments of love, lamentation, and military exhortations. Epigrams memorialized the dead in inscriptions across the Greek world. Iambic poetry relayed often satyrical ideas as close to natural speech as possible, and bucolic poetry in hexameter told stories of the lives of ordinary country people rather than of heroes.

There is much more to it, but you get the idea. Basically, all of our western literary traditions came out of Ancient Greece.

Not least among these genres was drama.

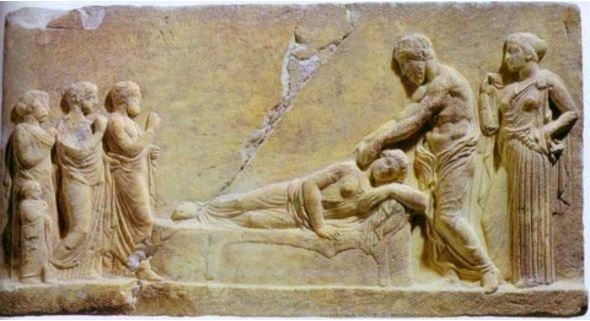

Relief of Maenads in ritualistic, frenzied dance honouring Dionysus.

The first thing we should look at is how the artform of ‘Drama’ came about as a form of entertainment.

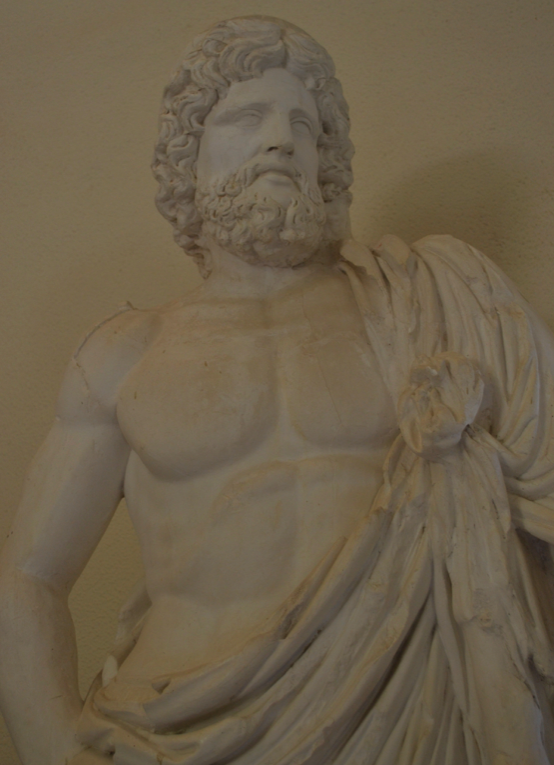

Similar to gladiatorial combat in Ancient Rome, which began as a religious ritual for the dead, drama in Ancient Greece was born out of religious practices, in particular, rituals honouring the god, Dionysus.

Early worship to Dionysus involved a darker side with ecstatic worship by female followers – the maenads of mythology – who were said to partake in frenzied dances and tear into animal, and sometimes human, flesh. In the sixth century B.C.E the worship of Dionysus involved obscene play, extreme emotion, singing, and dancing.

This was the genesis of Greek drama.

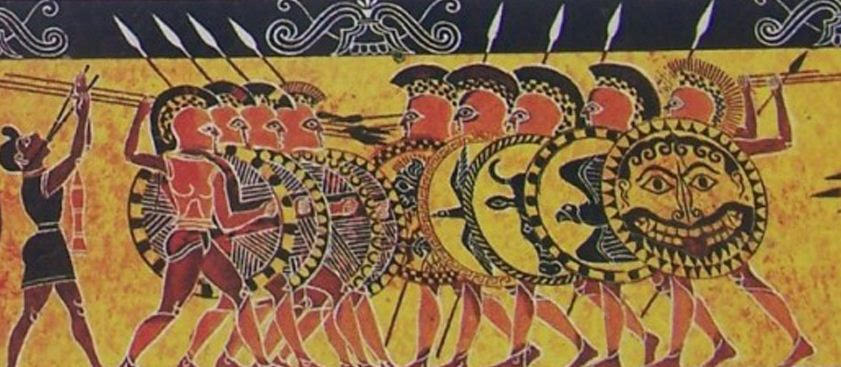

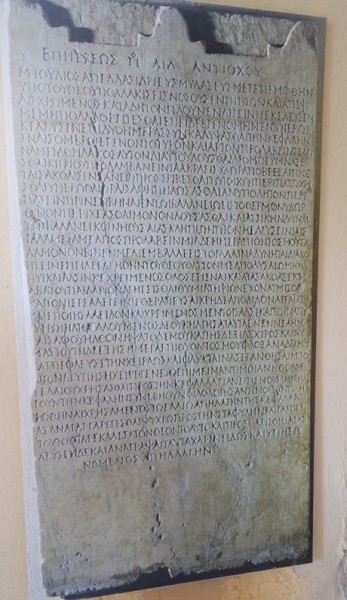

It was the tyrant Peisistratos (c. 600-527 B.C.E) who founded the city Dionysia of Athens, the great festival in honour of Dionysus, which involved a chorus of men singing and dancing for the god. Later, there were also rural Dionysia about Attica, with similar rituals. These early choruses could be as large as fifty people, but most were believed to consist of twelve to fifteen members.

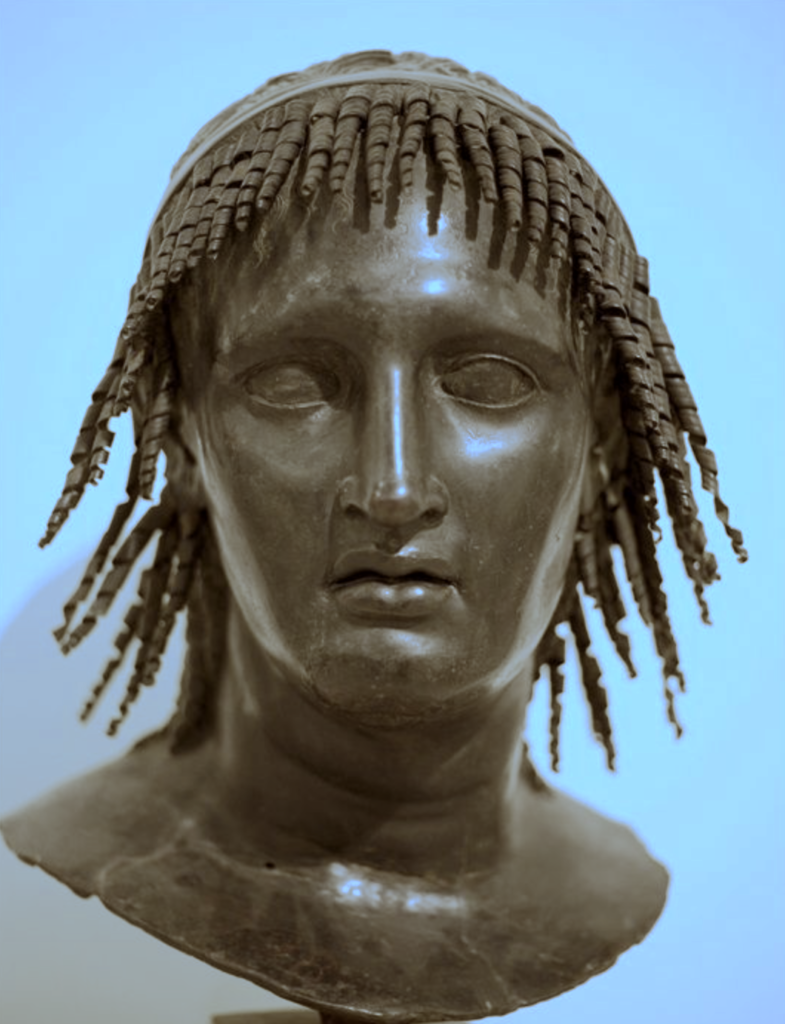

In the sixth century (c. 535 B.C.E), when a man named Thespis added himself to the ritual to deliver a prologue and interact with the Dionysian chorus, he is said to have become the very first actor, or ‘thespian’.

The addition of this one person to interact with the chorus is thought to be the beginning of true drama, the transition from religious ritual to dramatic performance for an audience.

Later, the playwright Aeschylus added a second actor and, after him, Sophocles added a third, and this became the standard number of actors for a while, in addition to the members of the chorus.

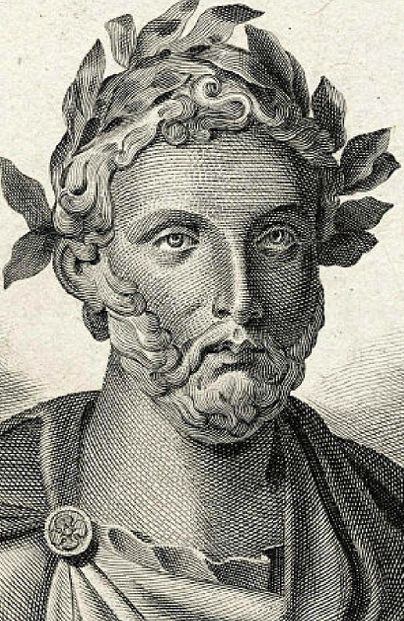

Roman bronze from Herculaneum thought to represent Thespis, the first actor.

In early drama, Greek comedies and tragedies were, more or less, musical productions. This was due to drama’s origins in dance and song for Dionysus. The members of the chorus played groups of people like the citizens of a city, dancing and singing.

These new dramas or plays, until the Hellenistic age, were performed in competitions as part of religious festivals like the Dionysia, the Lenaea (a winter festival to Dionysus), and the Panathenaea (to Athena Parthenos) at Athens. These theatre festivals were organized by the state.

For festivals, usually three poets were selected to have their work performed, and they were assigned an actor, or actors. The playwrights who participated wrote either tragedy or comedy, but not both. They usually submitted three tragedies on different themes and a satyr play, a short comedic piece (ex. Euripides’ Cyclops).

The winner of these competitions received a wreath. From about 499 B.C.E, the best actor also received a prize. All actors, even those playing female roles, were men. Oftentimes, the poets also acted in their own plays.

At Athens, when the Dionysia was in its infancy, the admission to watch the dramas was, apparently, about two obols. However, when Pericles was leading the way through Athens’ Golden Age, the state began to pay for admission to the theatre. In addition to male citizens, this sometimes also included non-citizens, or metics, as well as women and children who were, of course, accompanied by well-respected male citizens.

But before we get into the role that theatre played in Greek society, let’s first take a look at the types of drama that were performed, mainly Tragedy and Comedy.

It should be said at this point that, unfortunately, very little ancient drama has survived the centuries, and when it comes to tragedy, only Attic tragedies have survived.

Tragic dramas or plays from Ancient Greece seem to have originated in the mid-sixth century B.C.E in Attica or the Peloponnese, and the earliest surviving one we have is Aeschylus’ Persians (c. 472. B.C.E).

Ah! Miserable Fate! Black Fortune!

Black, unbearable, unexpected disaster!

A savage single-minded Fate has ravished the Persian race!

What troubles are still in store for me?

All strength has abandoned my body… my limbs… there is none left to face these elders.

Ah, Zeus! Why has this evil Fate not buried me, as well, send me to the underworld, among all my men?

(Aeschylus, Persians)

Tragedies were the first dramas and they were almost all based on mythological tales of gods, goddesses and heroes. They also had a standard format that comprised a prologos, sometimes presented by the chorus, and sometimes by an actor. Then there was a monologue or introduction. There was a parados, which was a song sung by the chorus as it entered. After that, there were various epeisodia, scenes with actors and the chorus, and during these epeisodia, stasima (songs) were performed. The play usually closed out with the exodos, the final scene or ‘exit’.

So, the first dramatic performances were tragedies and the genre gave rise to some of the most famous playwrights of the ancient world, including Aeschylus, Sophocles, and Euripides. However, tragedy began to decline by the end of the fourth century B.C.E in favour of comedy.

Melpomene – The Muse of Tragedy

The word comedy is derived from the Greek komoidia which comes from komos, a procession of singing and dancing revellers.

It is believed that comedy dates to the sixth century B.C.E and that it may have its roots in Sicilian or Megarian drama.

As with the tragedies, only Attic comedies survive to this day, and the earliest surviving one we have is Aristophanes’ Acharnians (c. 425 B.C.E). There were earlier comic poets such as Cratinus, Crates, Pherecrates, Eupolis and Plato (different to the famous philosopher), but none of their works survive.

Oh! by Bacchus! what a bouquet! It has the aroma of nectar and

ambrosia; this does not say to us, “Provision yourselves for three

days.” But it lisps the gentle numbers, “Go whither you will.”

I accept it, ratify it, drink it at one draught and consign the

Acharnians to limbo. Freed from the war and its ills, I shall

keep the Dionysia in the country.

(Aristophanes, Acharnians)

Ancient Greek comedy can be separated into three different types: Old Comedy, Middle Comedy, and New Comedy.

Comedies were humorous and uninhibited with many jokes about sex and excretions. They ridiculed and parodied contemporary characters, and an excellent example of this is Aristophanes’ ridiculing of Socrates in Clouds:

A bold rascal, a fine speaker, impudent, shameless, a braggart, and adept at stringing lies, and an old stager at quibbles, a complete table of laws, a thorough rattle, a fox to slip through any hole, supple as a leather strap, slippery as an eel, an artful fellow, a blusterer, a villain, a knave with one hundred faces, cunning, intolerable, a gluttonous dog.

(Aristophanes, Clouds)

Comedies also made fun of contemporary issues as well as gods, myths, and even religious ceremonies, making it a sort of acceptable outlet for mocking things that were otherwise sacred. This was a form of ‘free speech’ at work in the new Democracy of Athens.

All performances were staged during the city Dionysia and the Lenaea in Athens.

Old Comedy consisted of choral songs alternating with dialogue but it had less of a pattern than tragedy did. The chorus consisted of about twenty-four men and extras, and they often played animals. The actors wore grotesque costumes and masks.

Old comedies began with a prologos, and then the entrance of the chorus which proceeded to sing a parados, a song. Then there was the main event, the agon, a struggle, which was a debate or physical fight between two of the actors. There were songs during the action and subsequent scenes or epeisodia. The chorus also uttered a parabasis, which was a blessing on the audience. As with tragedy, comedies also ended with the final scene, or exodos.

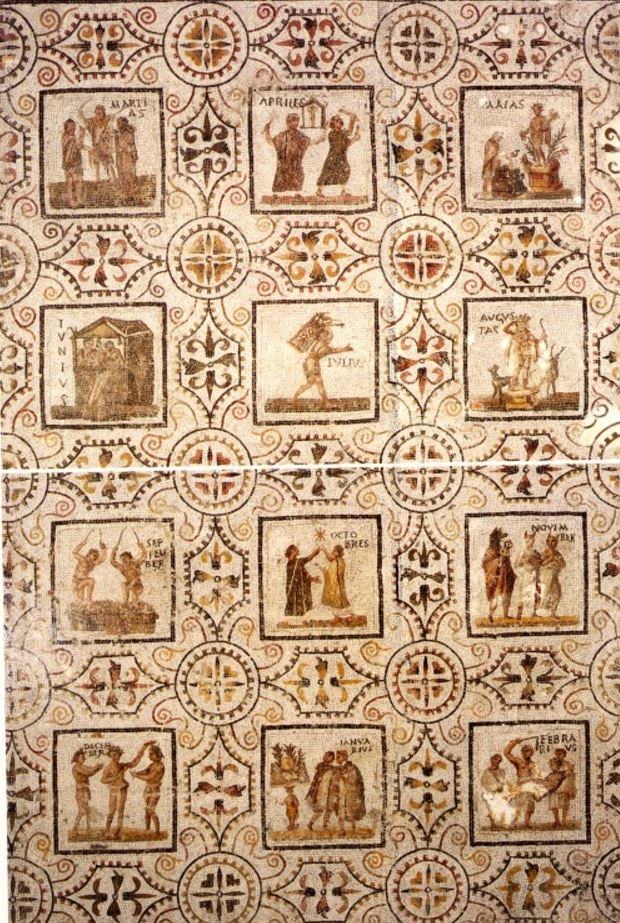

Second century C.E. mosaic depicting dramatic masks for Tragedy and Comedy

Middle Comedy in Ancient Greece was basically Athenian comedy from about 400-323 B.C.E. It developed after the Peloponnesian War and was more experimental with different styles beginning to emerge. Apparently it became quite popular and experienced a revival in Sicily and Magna Graecia.

Comic choruses began to play less of a role, and the parabasis was no longer used. Interestingly, the more grotesque costumes and phalluses were not as popular either.

Comedic plots based on mythology and political satire began to give way to less harsh humour and a focus on ordinary lives and issues.

Sadly, no complete plays from Middle Comedy survive, but some of the authors we know of were Antiphanes, Tubules, Anaxandrides, Timocles, and Alexis. Some might also class Aristophanes as one of the earliest poets of Greek Middle Comedy.

Thalia – The Muse of Comedy

Lastly, New Comedy is generally considered to be Athenian comedy from the death of Alexander the Great in 323 B.C.E to about 263 B.C.E.

In New Comedy performances, plays were five acts long and were interspersed with unrelated choral or musical interludes. They were generally set in Athens or Attica, and the actors wore masks, but now dressed in regular everyday clothes.

Though new comedies were Athenian, writers came from around the broader Greek world to Athens to write, and to see the plays.

The themes of these new plays were more human and relatable and dealt with things such as family relationships, love, mistaken identities (a throw-over from Middle Comedy), the intrigues of slaves, and long-lost children.

There were also stock characters that emerged such as pimps and courtesans, soldiers, young men in love, genial old men, and angry old men.

The themes and characters of Greek New Comedy greatly influenced Roman drama and which became so popular for the Roman theatre crowd.

Menander (c. 343–291 B.C.E)

Sadly, little survives in the form of Greek New Comedy, but much Roman comedy such as plays by Plautus and Terence, were based on those Greek plays, particularly Menander (c. 341-290 B.C.E). Other authors included Diphilus and Philemon.

It is a true tragedy that so much comedy does not survive. Menander alone is thought to have written over one hundred plays, and yet only a small fragment of a single one of his plays survives.

Thankfully, Roman playwrights such as Plautus and Terence used Menander’s plays as blueprints for their own and, as a result of that New Comedy format and formula, they gave rise to the western comedic tradition we are familiar with to this day through Shakespeare, Moliere, and others.

Now that we have briefly touched on the history of drama and plays, let’s take a look at where these plays were actually performed.

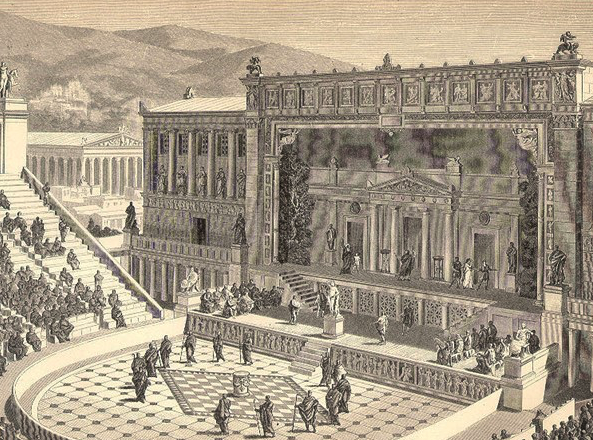

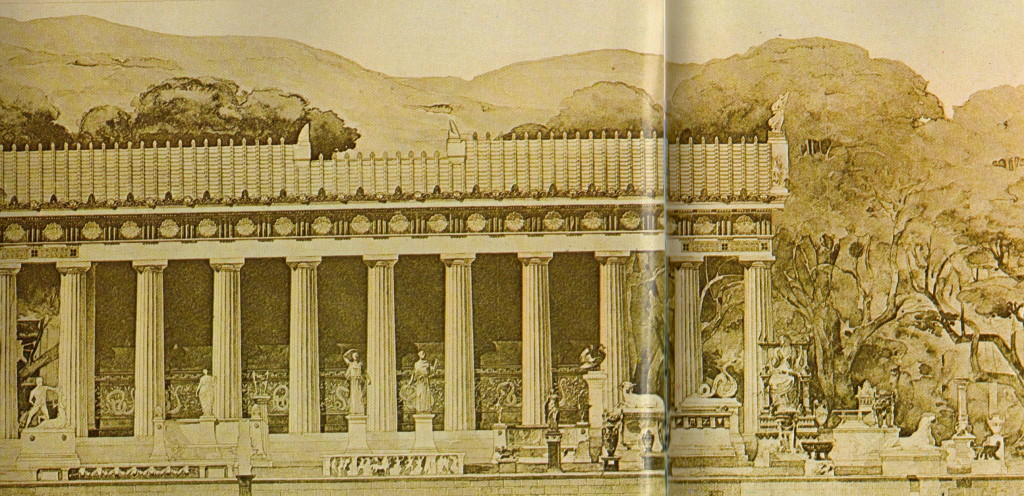

The Theatre of Dionysus, Athens

The word ‘theatre’ comes from the Greek word theatron which literally means ‘a place for watching’.

Theatres were built from the sixth century B.C.E onward. Most religious sites had a theatre and, as previously mentioned, they were used to celebrate festivals in honour of Dionysus.

Greek drama grew out of these religious festivals.

Early theatres could be temporary wooden structures, or a sort of scaffolding, but this practice was ceased after a deadly collapse in the Agora of Athens in about 497 B.C.E. After that, performances in Athens moved to the hillside where the theatre of Dionysus was built on the south slope of the Acropolis.

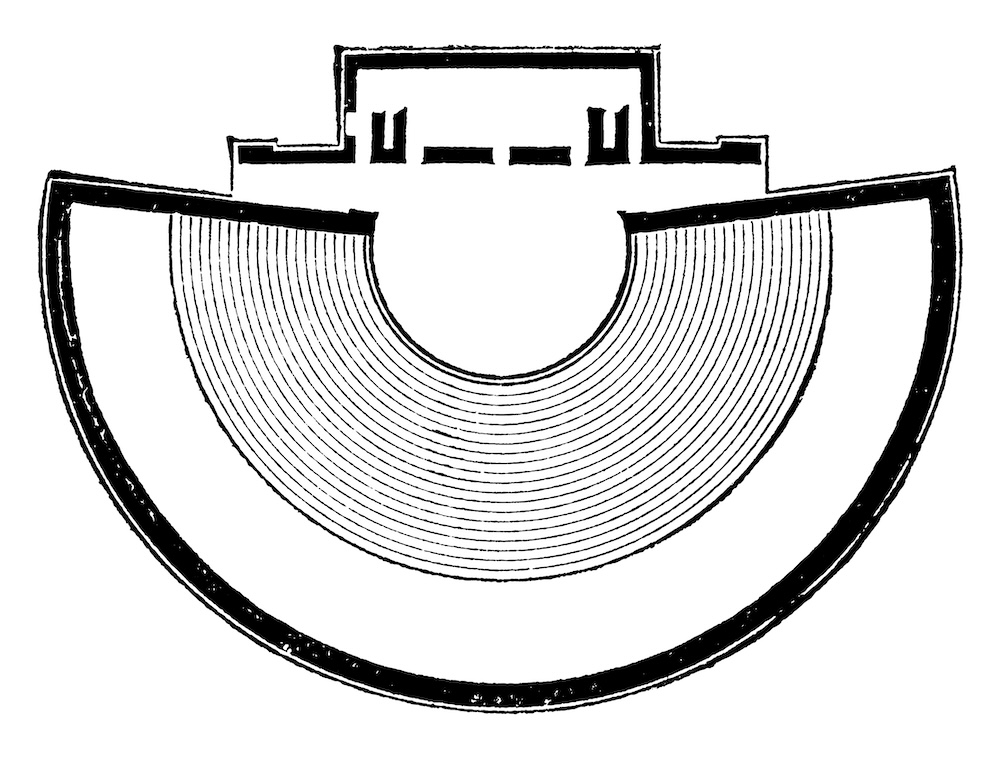

It became common practice to build theatres into the slopes or hillsides of natural hollows or, alternatively, into man-made embankments which supported tiers of seats on the hillside. Beginning in the fourth century B.C.E, theatre seating was built in marble. Theatres were generally D-shaped or on half-circle plans.

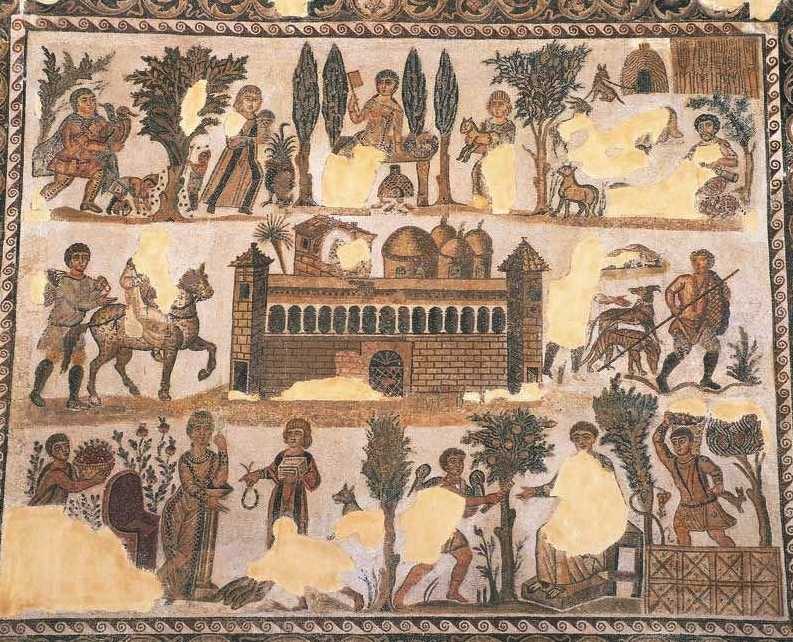

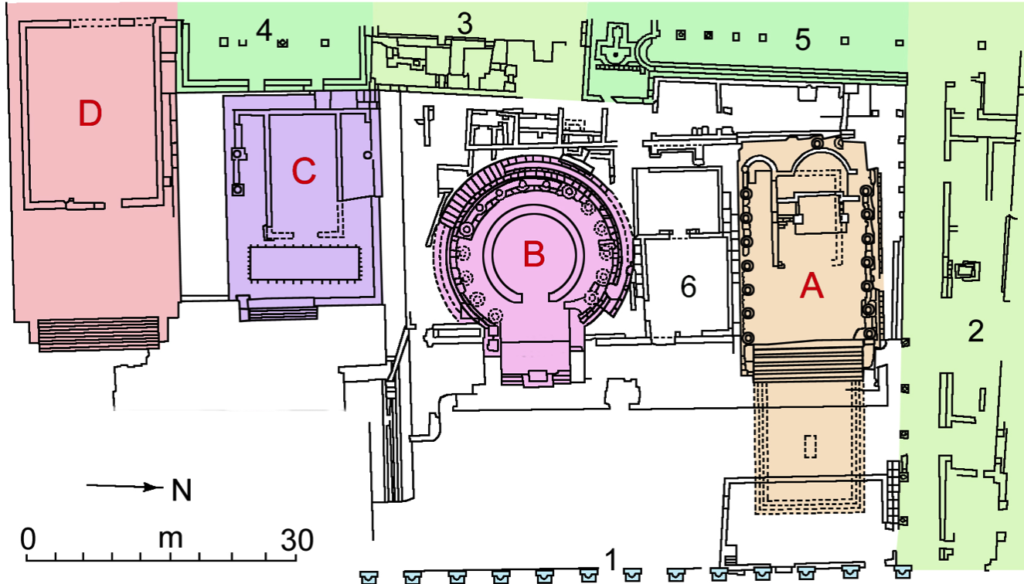

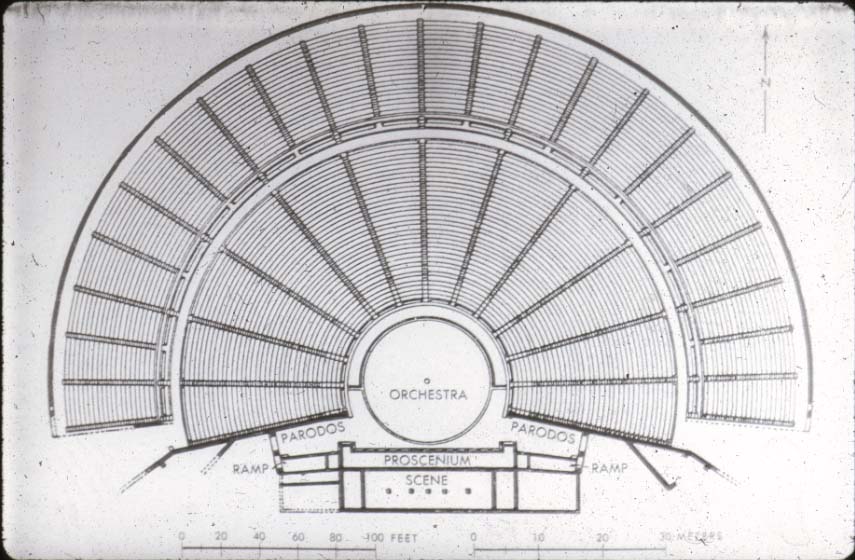

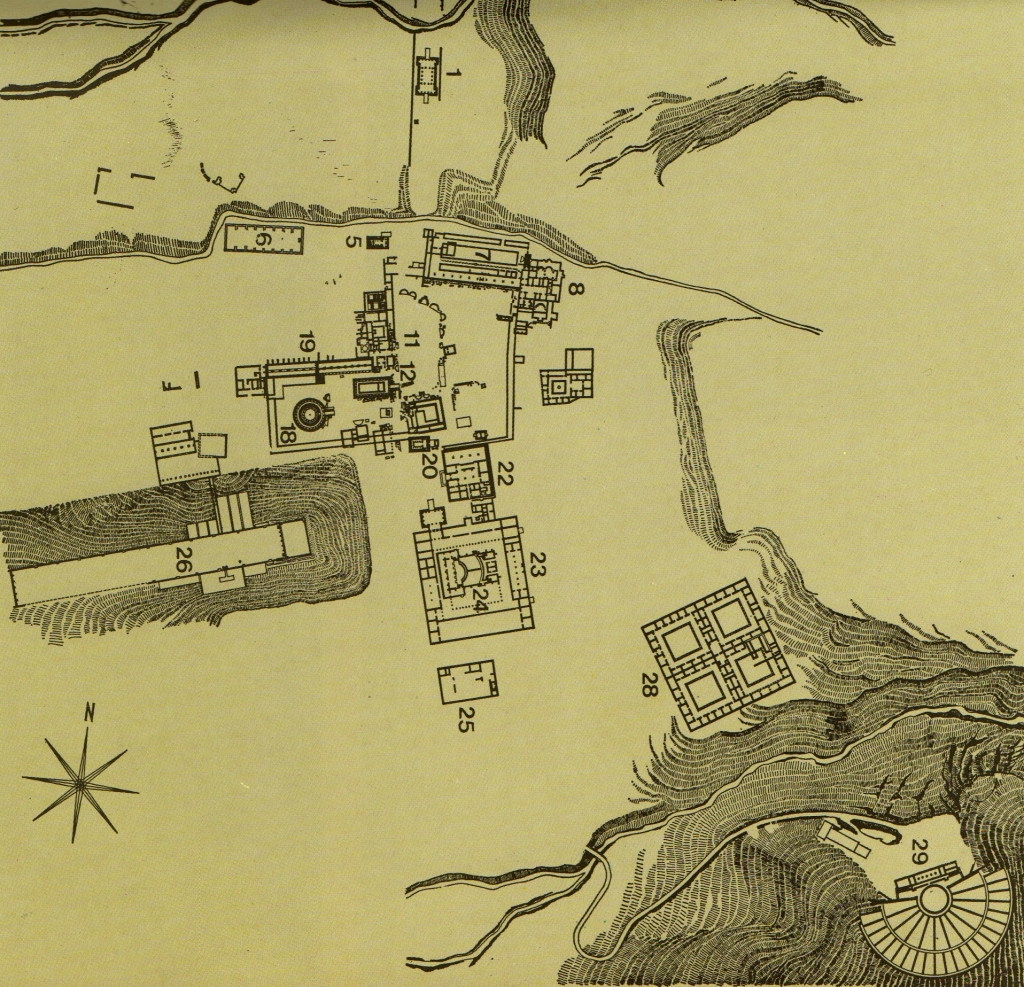

Ground Plan of the Ionian Greek theatre at Iassos.

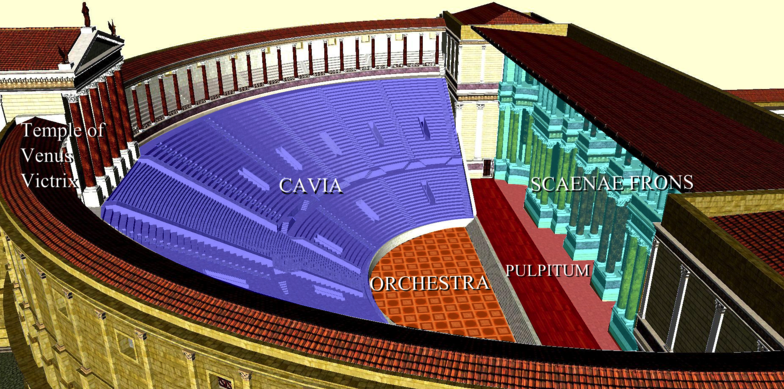

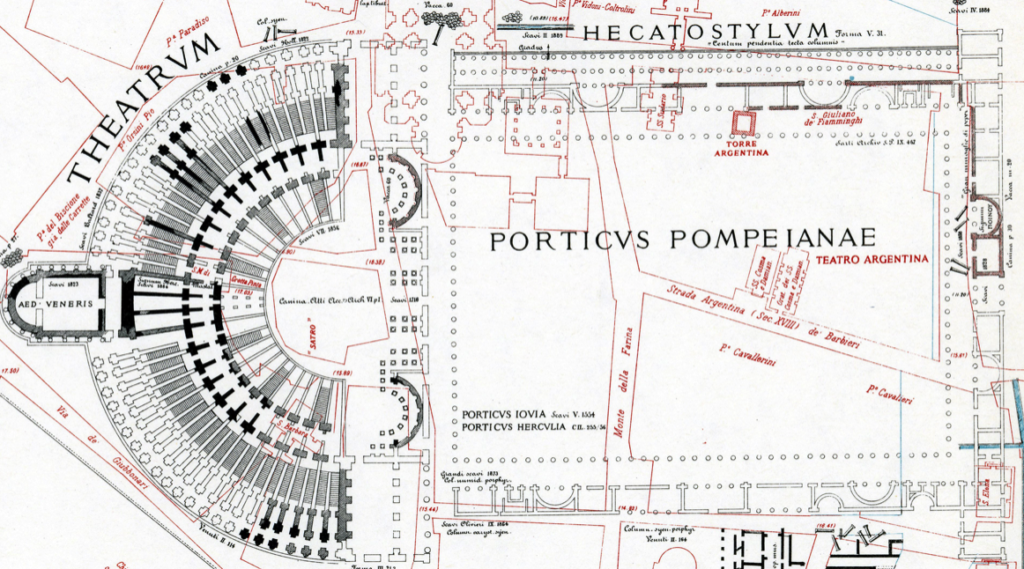

All theatres where drama was performed were ‘open-air’ and had several common components: the koilon (the seating area) where the seats in the front row were reserved for priests and officials, the orkestra (the circular performance space), and the skene (a building for storage and changing rooms for actors). Later, the skene became a stage with a backdrop called the proskenion (in Latin, the scaena frons). The addition of this stage (pulpitum in Latin) expanded the performance area.

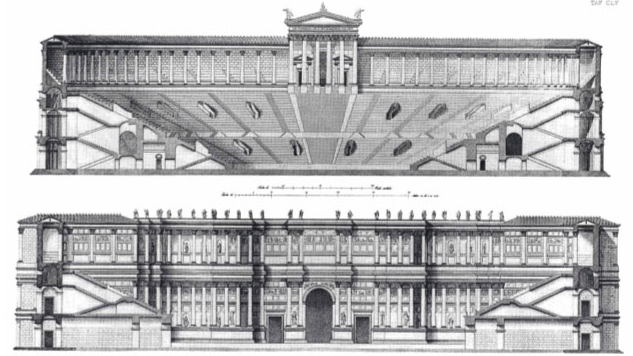

The other common performance space that was similar to theatres in Ancient Greece was the odeon (plur. odeia). These were usually roofed structures for listening to musical recitals and contests, poetry readings and other similar performances. Odeia were basically small theatres with a roof.

The first odeon of ancient Athens is thought to be that built by Pericles in the fifth century B.C.E. It was located directly beside the theatre of Dionysus and was a pyramidal structure made of wood with the roof supported by many columns. Some believe it was designed to resemble the tent of the defeated King of Persia.

Other odeia of ancient Athens included the Odeon of Agrippa in the Athenian Agora, and the stunning Odeon of Herodes Atticus on the southwestern slope of the Acropolis which is still used for performances to this day and which is featured in An Altar of Indignities.

Acropolis of Athens with the Odeon of Herodes Atticus before it on the left.

Today, theatre and dramatic performance is seen as more of a luxury in western society, something for the privileged few.

This was not the case in ancient Athens.

Though drama had religious beginnings, it evolved into an important way for Greeks as a society (albeit mostly for male citizens) to investigate the world in which they lived and what it meant to be human.

Aristotle believed that drama, tragedy in particular, had a way of cleansing the heart through pity and terror. It could purge men of their petty concerns and worries and, with this noble ‘suffering’, they underwent a sort of catharsis.

With the advent of philosophical thought, theatre and drama became the vehicle that encouraged average Greeks to become more ‘moral’ by helping them to process the issues of the day through both Tragedy and Comedy.

Rather than being a leisure activity for the elites, as it is perceived today, attending the theatre in ancient Athens was an important form of civic engagement after exercising one’s rights and performing one’s duties for the community (such as voting). Watching and experiencing tragedies and comedies with one’s fellow citizens became an important activity in the new Democracy of the day.

Not only did the drama and theatres of ancient Athens inspire their Roman successors, they also helped to shape the artistic traditions of western civilization.

For that, we should all be grateful.

Thank you for reading.

An array of Greek theatre masks

We hope that you’ve enjoyed this short post on drama and theatres in ancient Athens. There is a lot more to learn on this subject. We highly recommend the documentary series by Professor Michael Scott, Ancient Greece: The Greatest Show on Earth. You can watch the first episode HERE.

You can also read our popular articles on Theatres in Ancient Rome and Drama and Actors in Ancient Rome.

There are a lot more posts coming in The World of An Altar or Indignities, so make sure that you are subscribed to the Eagles and Dragons Publishing Newsletter so that you don’t miss any of them. When you subscribe you get the first book in our #1 best-selling Eagles and Dragons series for FREE!

If you haven’t yet read any books in The Etrurian Players series, we highly recommend you begin with the multi award-winning first book Sincerity is a Goddess: A Dramatic and Romantic Comedy of Ancient Rome.

In celebration of drama in the ancient world, be sure to check out our ‘Ancient Theatre’ Collection in the Eagles and Dragons Publishing AGORA on Etsy which features a range of ancient theatre-themed clothing, glassware and more! CLICK HERE to browse.

Stay tuned for the next post in this blog series in which we’ll be looking at travel and transportation in the Roman Empire.

An Altar of Indignities: A Dramatic and Romantic Comedy of Ancient Rome and Athens is now available in ebook, paperback and deluxe hardcover editions from all major online retailers, independent bookstores, brick and mortar chains, and your local public library.

CLICK HERE to buy a copy or get ISBN# information for the edition of your choice.

Brace yourselves! The Etrurian Players are back!

The Gods are Smiling!

The Gods are Smiling!