We’re half-way through our series on The World of Heart of Fire, and I hope you’ve been enjoying the posts thus far.

At this point, I think it apt to stop and look at one of the central aspects of the book, and the ancient Olympics in general: Religion.

It might be difficult for us to imagine today, especially when our modern Olympic Games are more dominated by advertisements and the media in general; we are more likely to associate Adidas and Coke with the Olympics rather than a deep-rooted belief if our chosen god or gods.

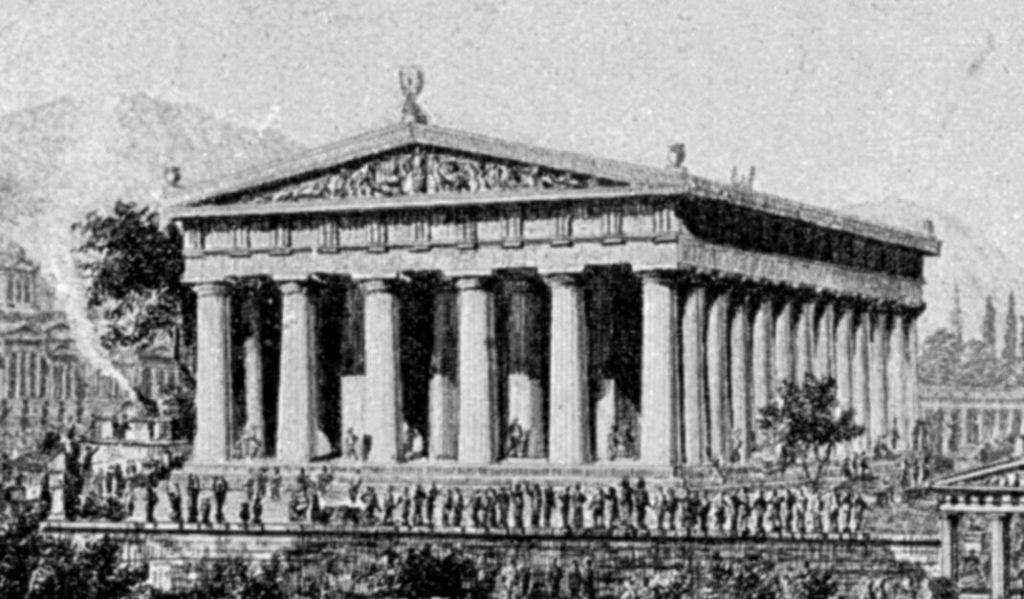

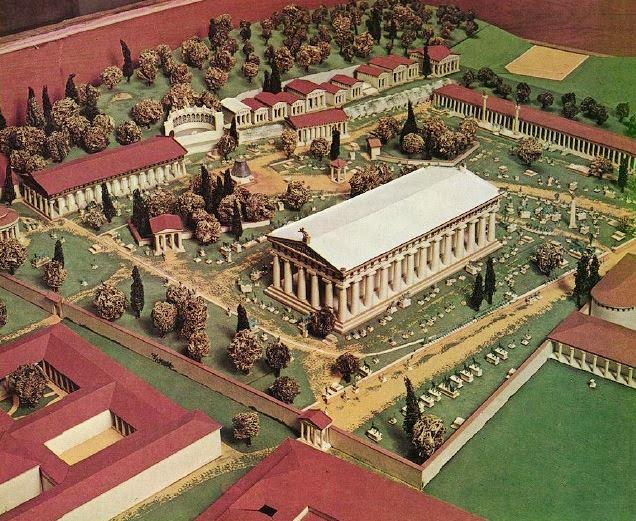

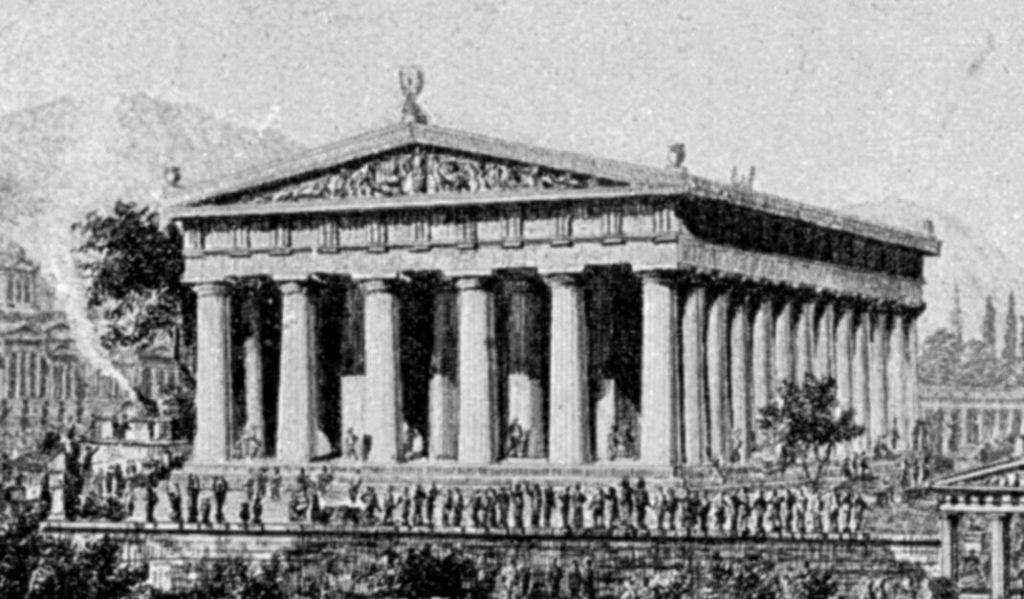

The Temple of Zeus at Olympia

But we are talking about the ancient world here, a time when the occurrence of the Olympic Games stopped wars across the Greek world in honour of the gods.

The Olympic Games were, first and foremost, a religious festival to honour Zeus.

But it is not as straightforward as that.

The concepts of ponos (one’s personal toil), philoneikia (love of competing), and philonikia (love of winning) were, as we have discussed in previous posts, central to a champion’s psyche, and to ancient Greek society in general.

To better oneself, to perfect oneself physically and mentally, was to honour the gods themselves.

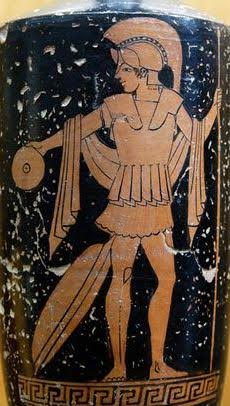

A Greek warrior pouring a libation to the Gods

In order to better understand the ancient world, we need to change our perspective. It’s important to remember that, though many people today don’t even think twice about religion, or believe in any sort of god, this was not so in Ancient Greece, or the rest of the ancient world for that matter.

In the ancient world, people believed the gods were everywhere, that they had a role to play in every aspect of life, whether one was starting a new business, setting out on a journey, going into battle, or lining up at the starting line for an Olympic foot race.

The gods affected everything, and so they were always given their due. The ancient Olympics were no exception to this.

Everything, every event at ancient Olympia was accented with religion and ceremony because the gods themselves were watching.

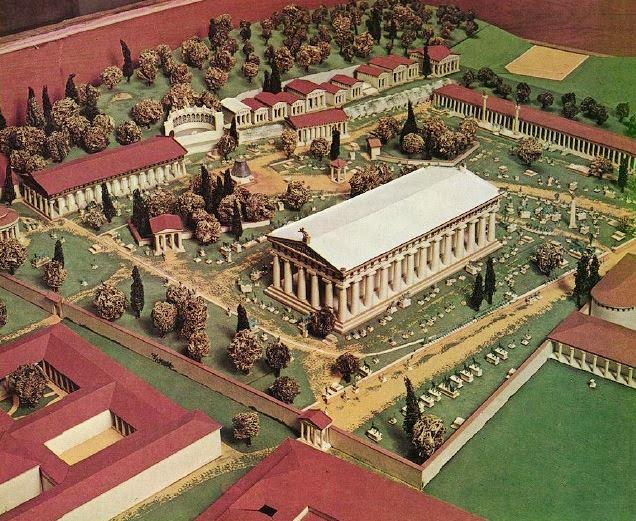

In the Altis alone there were sixty-nine altars where the Theokoloi, the priests of Olympia, competitors, trainers, and spectators could make offerings to the gods. These were in addition to the magnificent temples of Zeus and Hera which dominated the sanctuary.

Model of Olympia’s Altis

There was a whole industry of faith at Olympia as well, for in the south stoa and other places, vendors sold votive statues in clay or bronze, including figures of horses, chariots, running men, and tripods. One could also obtain animals for sacrifice, herbs, oils and more.

Individuals would have made offerings with their prayers for victory during their time at Olympia, prior to their events, and afterward.

There were sacrifices and offerings to the gods at the opening of every day, and before events such as the chariot race where an altar lay near the starting gates on the track of the hippodrome.

Votive figurines found at Olympia

There were also the marquee religious ceremonies of the Olympic Games which all athletes, trainers and others were expected to attend.

If you have watched the opening ceremony of a modern Olympic Games, you will know that the athletes always take the Olympic Oath.

In the ancient Olympics, the Oath-taking ceremony was a solemn occasion. The ceremony took place at an altar, beside the Bouleuterion, where a wild boar was sacrificed to Zeus Horkios (Zeus of Oaths).

This was overseen by the Theokoloi, and during the proceedings, athletes would swear that they had trained for at least ten months, and that they would compete honourably and not shame the games.

Another part of the Olympics we are all familiar with is the lighting of the Olympic flame.

Just to the northwest of the temple of Hera, was located a square enclosure and buildings called the Prytaneion. This was built in the sixth century B.C. and was used to put on banquets for Olympic victors and other officials.

More importantly, the Prytaneion was where the Eternal Olympic Flame burned beside the altar of the goddess Hestia, the goddess of the hearth and home. This was a sacred place at Olympia, and the fact that victors were celebrated beside the Eternal Flame speaks to the greatness, and divine sanction, of their achievement.

Ruins of the Prytaneion of Olympia

There were also religious relics on-site at ancient Olympia, making it not only a place for competition, but also of pilgrimage, perhaps more so the latter. These relate mainly to the story of Pelops and Hippodameia and that foundation myth of the Olympic Games.

You see, the ancient Greeks firmly believed in the tale of Pelops and Hippodameia, that particular hero-couple being the parents of Atreus, and grandparents of Agamemnon and Menelaus, the kings of Mycenae and Sparta.

To the Greeks visiting Olympia, this was history.

In the temple of Hera there was said to be an ornamental couch that served as a reliquary for Hippodameia’s bones, she who had helped Pelops win against her father and who, in thanks, established the Heraia, the games in honour of Hera in thanks for the victory.

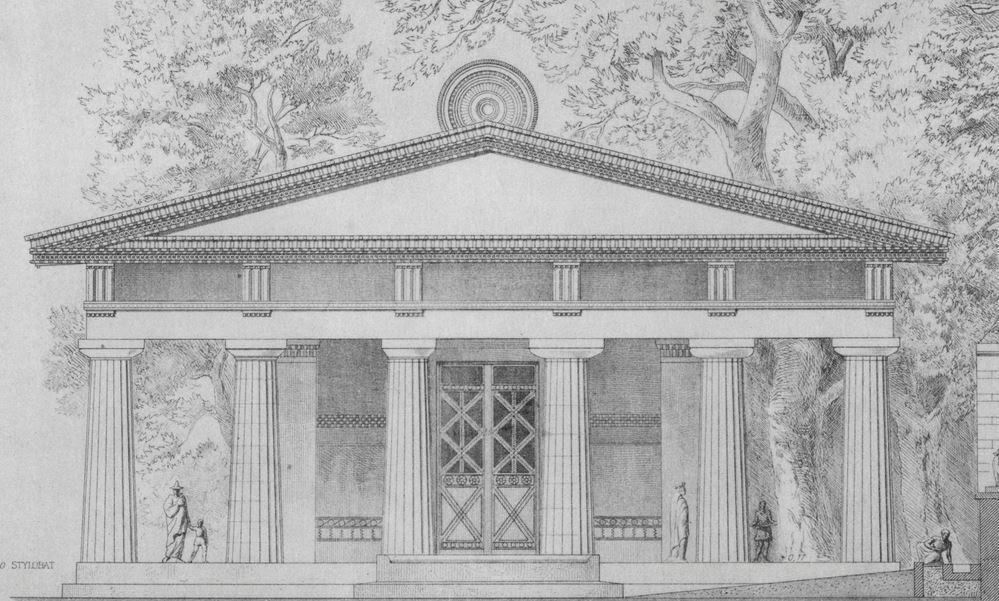

The Temple of Hera

In the treasury of the Sikyionians, at the north end of the Altis, in the shadow of the Hill of Kronos, there were relics of Pelops himself. One of these was his dagger, and the other was an ivory shoulder blade which travelled to Troy and back during the Trojan War.

The shoulder blade was said to be the one that the gods fashioned to replace the original mistakenly eaten by Demeter when Pelops’ wicked father, Tantalus, served his son to the gods at a banquet. The gods resurrected Pelops, and the rest is Olympic myth and history.

Pelops on East Pediment of Temple of Zeus – Pelops is to Zeus’ right, and Oinomaus to the left.

The cult of Pelops was powerful at ancient Olympia. Other than the cenotaphs, memorials, and horse burials that were said to be raised by Pelops and Hippodameia around Olympia, the focus of the cult was the Pelopion.

This was the barrow mound, or burial, of Pelops himself which was located in the middle of the Altis between the temples of Hera and Zeus. Some important scenes in Heart of Fire take place at this monument which was surrounded by a pentagonal enclosure, and where offerings were made to the shade of Pelops.

Pelopion (digital model created by University of Melbourne)

As mentioned before, religious ceremony was central to the Olympic Games, and the greatest of these ceremonies, most agree, happened on the third day of the games.

This was the hecatomb in honour of Zeus.

What is a hecatomb?

Well, it’s the sacrifice of one hundred cattle.

Relief of a sacrificial Hecatomb

Can you imagine what that must have been like…the sound of one hundred lowing cattle, the tang of blood in the air, and the smoke of the offerings as the bones wrapped in fat were offered to the gods, and the lean cuts were roasted for everyone at Olympia.

This was a solemn ritual that would have kept the Theokoloi and their attendants extremely busy, but it was all for Zeus, King of the Gods, and it did not get more serious than that.

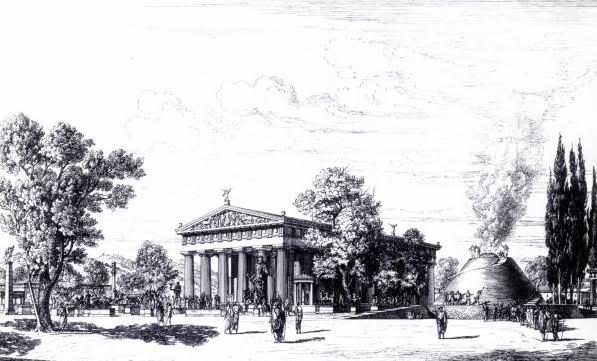

The sacrifices would have taken place at the Great Altar of Zeus which was located in the middle of the Altis. This altar was said to be a large, cone-shaped structure that was made up of piled ash and bones from centuries of offerings.

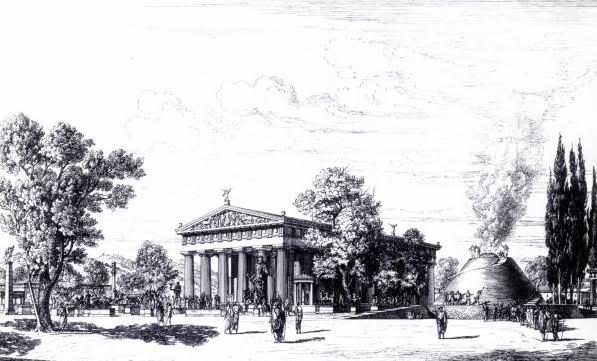

Illustration showing temple and great altar of Zeus, the cone-shaped structure to the right.

Pausanias describes the Great Altar where the hecatomb was offered to Zeus:

The altar of Olympic Zeus is about equally distant from the Pelopion and the sanctuary of Hera, but it is in front of both. Some say that it was built by Idaean Heracles, others by the local heroes two generations later than Heracles. It has been made from the ash of the thighs of the victims sacrificed to Zeus… (Pausanias Description of Greece 5.13.8)

There can be no doubt that the most important religious structures in the Altis of ancient Olympia were the temples of Zeus and Hera, the king and queen of the Olympian gods. These two ancient structures rose above the mass of altars, statues, and milling crowds, the powerful, archaic columns simple and strong, fitting for the dwelling place of the gods at Olympia.

Though the Games were dedicated to Zeus, Hera was certainly given her due at Olympia.

When Pelops was victorious in his chariot race against Hippodameia’s father, Oinomaus, Hippodameia established the Heraia, the games in honour of Hera, in thanks for the victory. This was the only event for women that was held on the sacred ground of Olympia.

As mentioned, Hippodameia’s bones were kept in a couch inside the temple of Hera, but also kept within that temple were the twenty shields that were used in the Olympic hoplite race, the hoplitodromos.

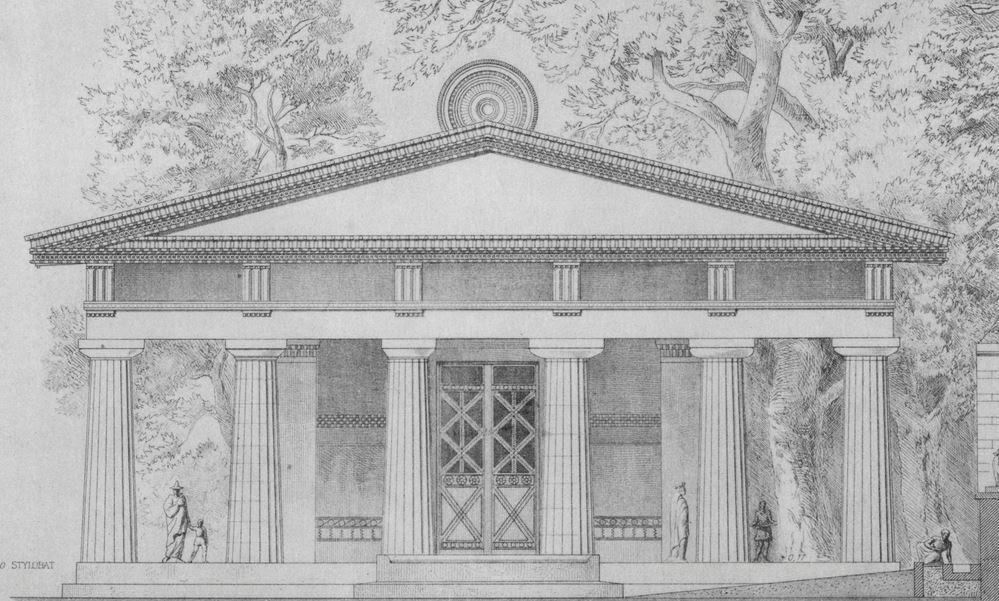

Temple of Hera artist impression showing the acroterion at the top, shaped like peacock feathers, a symbol of Hera

The centrepiece of the Altis however, was indeed the temple of Olympian Zeus.

This temple contained the titanic chryselephantine statue of Zeus, created on site by the sculptor Pheidias, whose workshop was just outside the Altis. The statue was made of ivory and gold and portrayed Zeus seated on his throne with the goddess Nike in his hand, that goddess who crowned the victors.

Now you know where the shoe company gets its name!

Temple of Zeus ruins

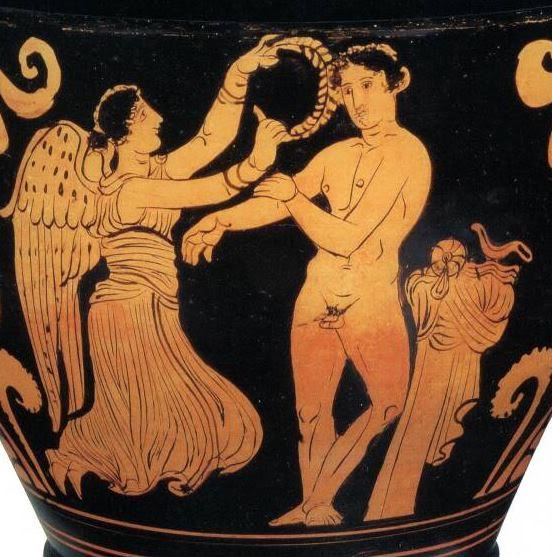

The victory ceremony was a solemn religious occasion that happened after a competitor was proclaimed ‘best among the Greeks’ and given a linen headband as a sign of their victory.

After that, there was a procession of victors through the Altis to the temple of Zeus, with onlookers showering the victors with phylobolia, fresh flowers and greens.

Before Zeus, men were crowned with the sacred olive crowns in a ceremony called the ‘binding of the crown’. These crowns were made from boughs of the sacred olive trees that were located near the temple of Zeus.

It may be hard for us to imagine this moment, when an ancient athlete was crowed before the gods. It was indeed a deeply religious moment, with the singing of hymns in honour of Herakles, Zeus’ son.

It was believed that men won, not only by skill and training, but more so by divine grace. Sacrifices were made at this time, and then victors enjoyed a meal in the Prytaneion in the presence of the eternal Olympic flame.

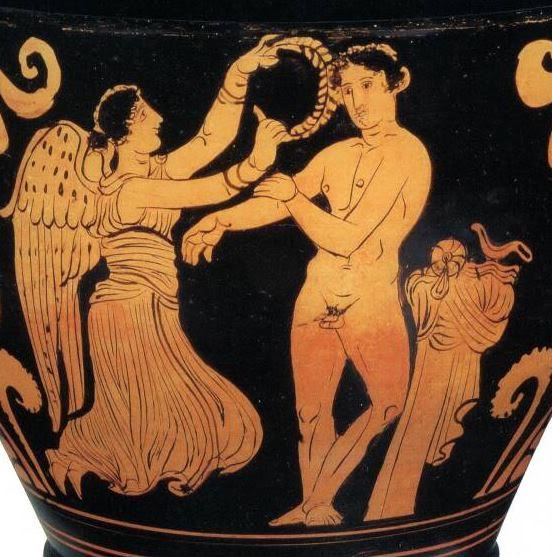

Nike, Goddess of Victory, Crowning an Olympic Victor

Of course, ancient sources are sparse, and the exact details of every aspect of ceremony at the ancient Olympics cannot be known for sure. However, what has come down to us paints enough of a picture to help us understand that the ancient games were not just about running and pounding away at one’s opponent.

Attending the ancient Olympics, for ancient Greeks, was a pilgrimage that deserved respect, a sacred rite to honour the gods through skill and performance, and, if the gods smiled, through victory.

If you ever get a chance to walk the grounds of ancient Olympia, you will certainly get a sense of the deep connection between religion and the Olympic Games.

In the next post, we will look at one of the oldest Olympic sports that plays a big role in Heart of Fire: Boxing.

Thank you for reading!