Greetings Readers and History-Lovers!

Welcome back to The World of An Altar of Indignities, the blog series in which we’re taking a look at some of the research that went into our dramatic and romantic comedy set in ancient Rome and Athens.

If you missed Part VIII on the Panathenaea of ancient Athens, you can read that by CLICKING HERE.

In Part IX, we’re going to take a brief look at spirits in Roman religion. After all, ancient Romans could be highly superstitious and, in the ancient world, spirits were indeed thought to be everywhere.

The story of An Altar of Indignities is no exception to this, and there is one particular spirit who does indeed try to upstage our troupe of players!

We hope you enjoy this fascinating post about numina Romana…

In all of the many years I’ve been researching and writing about the world of ancient Rome, the topic of Roman religion has been a constant source of fascination for me as an author and historian. Many of my readers have echoed this sentiment too, and have pointed out that they love the inclusion of that aspect of Roman life.

You can read more on writing about Roman religion HERE, and be sure to check out our popular article on sacrifices in Roman religion by CLICKING HERE.

But what is it that fascinates us about Roman religious beliefs and practices?

For me, it is the openness and flexibility of Roman religion. Mortals had a closer, perhaps more symbiont, relationship with their gods. The religion was highly customizable.

But, like any other religion, there was a sort of evolution over time. Most religions today believe in a spirit realm, that spirits are present, and often they are menacing.

It was a little different in Roman religion. We are all familiar with the gods of the Roman pantheon – Jupiter, Juno, Minerva etc. – but what you may not know is that sprits of various kinds played a central role in Roman religious beliefs and practices.

In this short post, we’re going to be taking a look at the various kinds of spirits that Romans believed in.

In the world of ancient Rome, spirits were known as numina (sing. numen). These were divine spirits or powers that were present everywhere in life, people, and places. They were not anthropomorphic at first.

Originally, Romans may have believed that a numen was a place itself, such as a wood, river, spring, or cave etc., and that that place was supernatural or divine.

Gradually, however, with the influence of Greek religion, Romans came to believe that these places were inhabited or protected by these numina or spirits. Eventually, these numina were given names and traits. In many instances they began to take form.

Illustration of a statue of Sancus found in the Sabine’s shrine on the Quirinal (Wikimedia Commons)

Numina were present in material things such as crops, but also in actions such as travel.

These spirits could also inhabit more abstract ideas such as Discipline (the Goddess Disciplina), Virtue (the Goddess Pietas), or Trust and Honesty (the God Sancus). Even the living emperor, his role as such, had a numen that was worshipped by the people.

Truth be told, there are myriad numina in Roman religion, and most of them were nameless. Most Romans honoured the numen or numina that were related to their home or occupation.

But what were the various types of spirits or numina whom Romans believed in?

Let us go through the most prominent ones…

Bronze genius depicted as paterfamilias (1st century CE) Wikimedia Commons

In addition to the main gods, goddesses and heroes who were worshipped in ancient Rome, there were many types of numina:

The Genii (sing. Genius) literally mean the ‘begetter’. Early on, this was a man’s guardian spirit who helped him to beget children. This spirit was honoured on the birthday of the paterfamilias, the man in whom it lived.

You can read more about the paterfamilias in Roman society HERE.

The genius was symbolized by the snake which was a symbol of household protectors.

Over time, people and places came to have genii. For example, the spirit of a place was the genius loci, and if one was in a place where one did not know whom to worship or make offerings to, one would pray to the genius loci of that particular place.

Lararium in the House of the Vettii Pompeii. It depicts the ancestral genius (upper centre) flanked by the Lares, with a serpent below. (Wikimedia Commons)

The next group of spirits we’re going to look at are the Lares (sing. Lar).

These were very important numina in the world of ancient Rome. The Lares were ancient and mysterious spirits whose original character is unknown. It is thought that early on, they were guardians of farmland.

The Lares evolved into protective household gods. Every household, however grand or simple, had them. They were worshipped at what was called a lararium, a shrine dedicated to them, and prayers to the Lares were led by the paterfamilias.

These numina were worshipped on the Kalends (first day), the Nones (ninth day), and the Ides (fifteenth day) of every month.

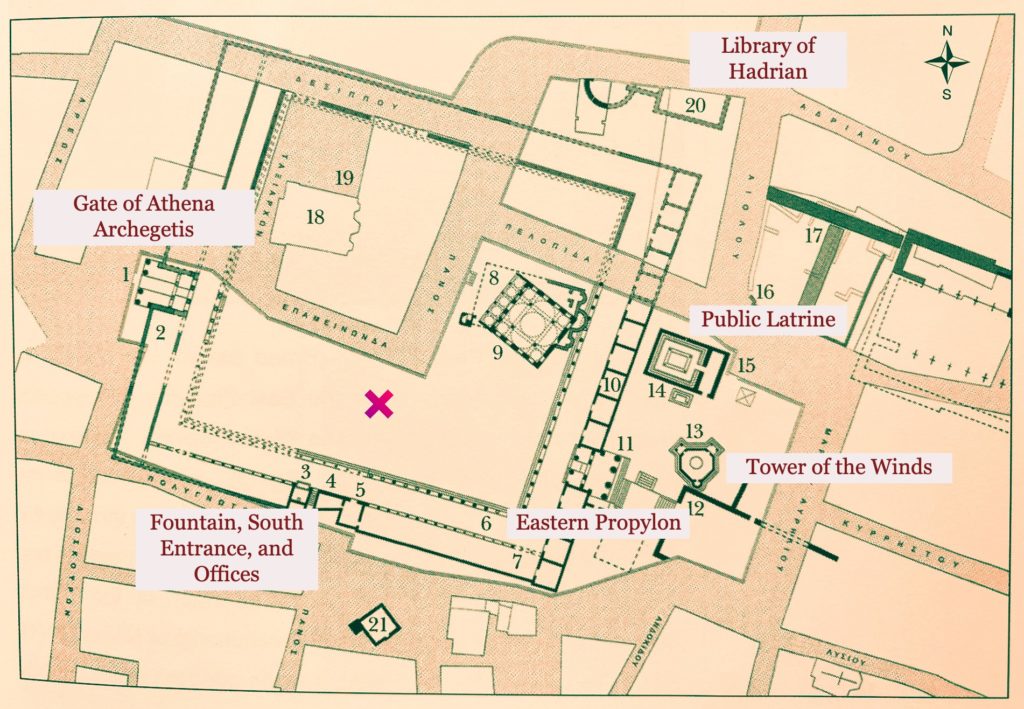

There were also Lares of other, less personal places such as neighbourhoods (Lares Compitales), and cities (Lares Publici or Lares Praestites). In Rome, the Lares Praestites had a temple at the beginning of the Via Sacra.

The Lares Compitales were worshipped on the festival of Compitalia, a Roman agricultural festival, perhaps alluding to their rural roots. The Lares in general had their festival at Rome on December 22.

Offerings of food to the Penates were burned on the domus hearth fire

Another group of spirits who went hand in hand with the Lares were known as Di Penates. These were also protective spirits of the household, but more specifically the pantry.

At every meal, a portion of the food was set aside for the Penates, and this was offered to them on the hearth fire. Salt and fruit was always left on the table for them.

The festival of the Penates was held on October 14.

Di Penates were also not limited to a household, the same as the Lares. The Penates Publici were attached to the Roman state and were worshipped alongside Vesta, Goddess of the Hearth, in her temple.

Honouring dead family members

Now we move into the realm of the remembrance and honouring of the spirits of the dead.

The Manes, the Roman spirits of the divine dead, were a group that Romans took very seriously.

The dead were to be respected, remembered and honoured in ancient Rome, and there were several festivals at which this was done: Feralia, Parentalia, and Lemuria.

The belief was that every dead person, no matter the age or gender, had its own spirit, and that spirit was known as a manes (yes, plural and singular forms are the same here).

The Manes were mainly honoured as the Manes Familiae, or more commonly as Di Parentes, the ‘Dead of the Family’.

“To the spirits of the dead: For Cornelia Frontina, who lived 16 years and 7 months, her father, Marcus Ulpius Callistus, freedman of the emperor, overseer in the armory of the Ludus Magnus, and Flavia Nice, his most virtuous wife, set up this [monument] for themselves, their freedmen and freedwomen, and their descendants.”

Graves were also important, and to be respected, as is evidenced by the many memorials and monuments that line the roads leading into Rome, or that dot the grounds of many ancient necropoli. Graves were considered dis manibus sacrum, ‘sacred to the divine dead’, and this was inscribed on monuments. Later, individuals were named in grave dedications that sometimes told their stories.

Ancestor worship was a part of honouring the Manes, and they were remembered in households by the imagines which were wax masks or busts of the deceased. It is believed this was the case because the Romans believed that the life source was in the head, and not the heart.

Imagines later became works of art to decorate homes, but the old religious significance never really disappeared.

Romulus and Remus upon an altar dedicated to Mars and Venus (from Ostia)

The spirits of the dead were not always entities whose remembrance gave comfort to the living. There was another group of spirits who were to be dreaded and propitiated: Lemures.

Lemures were spirits of the dead of a household, or place, who haunted the domus or location, those who had been violently murdered or met an untimely end. These numina were hostile, and often the Lemures of children were feared the most.

They were of a very different character to the Manes Familiae.

The poet Ovid, in his Fasti, relates a story on the origins of Lemures and the festival of Lemuria:

Why the day was called Lemuria, and what is the origin of the name, escapes me; it is for some god to discover it. Son of the Pleiad, thou reverend master of the puissant wand, inform me: oft hast thou seen the palace of the Stygian Jove. At my prayer the Bearer of the Herald’s Staff (Caducifer) was come. Learn the cause of the name; the god himself made it known. When Romulus had buried his brother’s ghost in the grave, and the obsequies had been paid to the too nimble Remus, unhappy Faustulus and Acca, with streaming hair, sprinkled the burnt bones with their tears. Then at twilight’s fall they sadly took the homeward way, and flung themselves on their hard couch, just as it was. The gory ghost of Remus seemed to stand at the bedside and to speak these words in a faint murmur: “Look on me, who shared the half, the full half of your tender care, behold what I am come to, and what I was of late! A little while ago I might have been the foremost of my people, if but the birds had assigned the throne to me. Now I am an empty wraith, escaped from the flames of the pyre; that is all that remains of the once great Remus. Alas, where is my father Mars? If only you spoke the truth, and it was he who sent the wild beast’s dugs to suckle the abandoned babes. A citizen’s rash hand undid him whom the she-wolf saved; O how far more merciful was she! Ferocious Celer, mayest thou yield up thy cruel soul through wounds, and pass like me all bloody underneath the earth! My brother willed not this: his love’s a match for mine: he let fall upon my death – ‘twas all he could – his tears. Pray him by your tears, by your fosterage, that he would celebrate a day by signal honour done to me.” As the ghost gave this charge, they yearned to embrace him and stretched forth their arms; the slippery shade escaped the clasping hands. When the vision fled and carried slumber with it, the pair reported to the king his brother’s words. Romulus complied, and gave the name Remuria to the day on which due worship is paid to buried ancestors. In the course of ages the rough letter, which stood at the beginning of the name, was changed into the smooth; and soon the souls of the silent multitude were also called Lemures: that is the meaning of the word, that is the force of the expression. But the ancients shut the temples on these days, as even now you see them closed at the season sacred to the dead. The times are unsuitable for the marriage both of a widow and a maid: she who marries then, will not live long. For the same reason, if you give weight to proverbs, the people say bad women wed in May. But these three festivals fall about the same time, though not on three consecutive days.

(Ovid, Fasti, Book V; trans. James G. Frazer)

It is quite a moving beginning the tradition. As relayed by Ovid, the festival of Lemuria did not fall on three consecutive days, but was celebrated on May 9th, 11th, and 13th.

Les Parques (The Parcae, ca. 1885) by Alfred Agache

There were other numina or spirits that took on a more divine nature in Roman religion.

The Fata (Fates) or the Parcae, were the powers of Destiny, and they were known by the names Nona, Decima and Morta.

Originally, the Parcae, believed to have been influenced by a triad of Celtic goddesses, may have been birth goddesses, but this role evolved into something more all-encompassing.

One could not escape the Parcae, or rather, Fate.

Similarly, one could also not escape the Furies.

The Remorse of Orestes, where he is surrounded by the Erinyes, by William-Adolphe Bouguereau, 1862

Influenced by Greek beliefs, the Furiae were goddesses of terror to the Romans, similar to the Greek Erinyes.

The Furiae were female spirits who carried out the vengeance of the Gods on mortals. If you’ve read our popular book, Saturnalia, these anima will be familiar to you.

These numina carried out their duties on Earth as well as in the Underworld. They were everywhere and could not be escaped from. Traditionally, there were three Furiae: Tisiphone, Megara, and Alecto. Roman tradition also sometimes included two more: Adrasta and of course, Nemesis.

Whoever you were, and whatever you had done, the Furiae were to be respected and feared.

Hylas and the Nymphs by Waterhouse (1896)

Lastly, we come to perhaps one of the most well-known groups of numina in Greek and Roman religion: the Nymphs.

The Nymphs were female nature spirits of objects or places such as trees, springs, rivers, mountains etc.

They were everywhere and were usually young and beautiful, and loved music and dancing.

The Nymphs were not immortal as some might think, but they lived much longer than humans.

The cult of the Nymphs was popular in Roman religion, perhaps not only because they were young and beautiful and not menacing, but perhaps also because they were everywhere.

And like other Roman divinities and numina, they were more relatable to humans than the gods of later, ‘revealed’ religions.

Nymphaeum, or shrine dedicated to the Nymphs (Jerash, Jordan)

Those are the primary numina of Roman religion. We hope that you have learned something new in this short post.

While it is true that the belief in spirits spans most world religions, the Roman beliefs, to us, are utterly fascinating for they are a mixture of the divine and departed, of nurture and menace, of fear and inspiration.

Just as Romans lived with and honoured their Gods on a daily basis, so too did the spirits of their world roam alongside them.

Thank you for reading.

CLICK HERE to buy a copy and get ISBN#s information for the edition of your choice.