ancient Greece

The World of An Altar of Indignities – Part III – Roman Monuments of Athens

Welcome back to The World of An Altar of Indignities, the blog series in which we share the research for our latest novel, An Altar of Indignities: A Dramatic and Romantic Comedy of Ancient Rome and Athens.

If you missed the second post on travel and transportation in the Roman Empire, you can read that by CLICKING HERE.

In part three of this blog series, we’re going to be looking at some of the Roman monuments and additions to the great city of Athens that appear in the novel.

Let’s get started!

Pericles’ funeral oration for the dead of the Peloponnesian War in the Kerameikos of Athens by Philipp Foltz (1852)

When we think of Athens today, we inevitably think of that ‘Golden Age’ city which Pericles, after the destruction wrought by the war with Persia, helped to build into a beacon of light and learning for the world.

There is the ancient Agora with its restored stoa of Attalus, one of a few such structures, myriad statue bases and altars. There is, of course, the beautiful temple of Hephaestus overlooking the Agora where other temples of Ares, Apollo, and Aphrodite were located. This vast area was the beating heart of ‘Golden Age’ Athens.

There is the Kerameikos district about the great Dipylon Gate of Athens’ ancient walls where the road to Eleusis leads through the cemetery where Pericles gave his famous funeral oration honouring the dead of the Peloponnesian war.

On the south side of the Acropolis, there is the Pnyx where the citizens of Athens met to participate in the new experiment known as ‘Democracy’, as well as the magnificent theatre of Dionysus where the first dramas in history were performed, and the Odeon of Pericles beside the theatre where musical and poetry performances entranced Athenian audiences.

Painting of ‘Golden Age’ Athens by Leo von Klenze (1846)

Above all of these monuments and more was the temple of Athena Parthenos, the Parthenon, the crowning achievement of ancient Athens that hovered like Olympus above the city.

The remains of the ‘Golden Age’ of ancient Athens are everywhere, and history lovers flock to it as much today as they did in ages past.

However… Our story takes place in Roman Athens in the early third century C.E. What did Athens look like long after the setting of the city’s ‘Golden Age’? What did the Romans ever do for Athens?

The answer is, quite a lot.

Sadly, unlike many of Rome’s relationships, it started off with the usual violence that preceded the productive calm and beauty of the Pax Romana.

The Roman occupation of Greece really began in 146 B.C.E with the defeat and total destruction of the city of Corinth by Quintus Caecilius Metellus Macedonicus who arrived from the north, and then Consul Lucius Mummius.

Then, in 88 B.C.E when Athens and other cities revolted against Roman occupation, Lucius Cornelius Sulla devastated Greece. Athens suffered greatly at the hands of Sulla and much of that ‘Golden Age’ city was destroyed or damaged during his siege of the Acropolis.

Subsequently, Athens and the rest of Greece were to remain a part of the Roman Empire after the battle of Actium in 31 B.C.E when Octavian (later Emperor Augustus) crushed the forces of Mark Antony and Queen Cleopatra thus heralding the end of the Hellenistic Age and beginning the long period of Roman hegemony over the Mediterranean.

Emperor Augustus

After all the destruction, however, under Roman rule Athens began to experience a revival with several rulers really enriching the city for all that it had contributed. You see, many Romans, especially educated ones, really admired Athens and its legacy, a legacy from which Rome had adopted a great deal.

Under Roman rule, Athens saw the construction of several Roman monuments that still stand to this day, at least partially. We are going to take a brief look at a few of them.

Not only were improvements and repairs made to existing monuments, but completely new ones were added to his ancient city, including several public bath houses that were erected in various places.

Vintage engraving of the Theatre of Dionysus with the Roman scaena frons

Among the existing monuments that were repaired and updated was the ancient theatre of Dionysus where the great theatre festivals, such as the Dionysia, took place. At various stages over the Roman period, the theatre was renovated and expanded with more seating and a large scaena frons, or stagehouse.

Fifteen years or so after the Battle of Actium, a new odeon was built around 15 B.C.E in the middle of the Ancient Agora by the general, Marcus Vipsanius Agrippa. This covered, two-storey structure could seat about one thousand people and is still visible today by the carved tritons on its north side.

Recreation of the exterior and interior of the Odeon of Agrippa in the ancient Agora of Athens

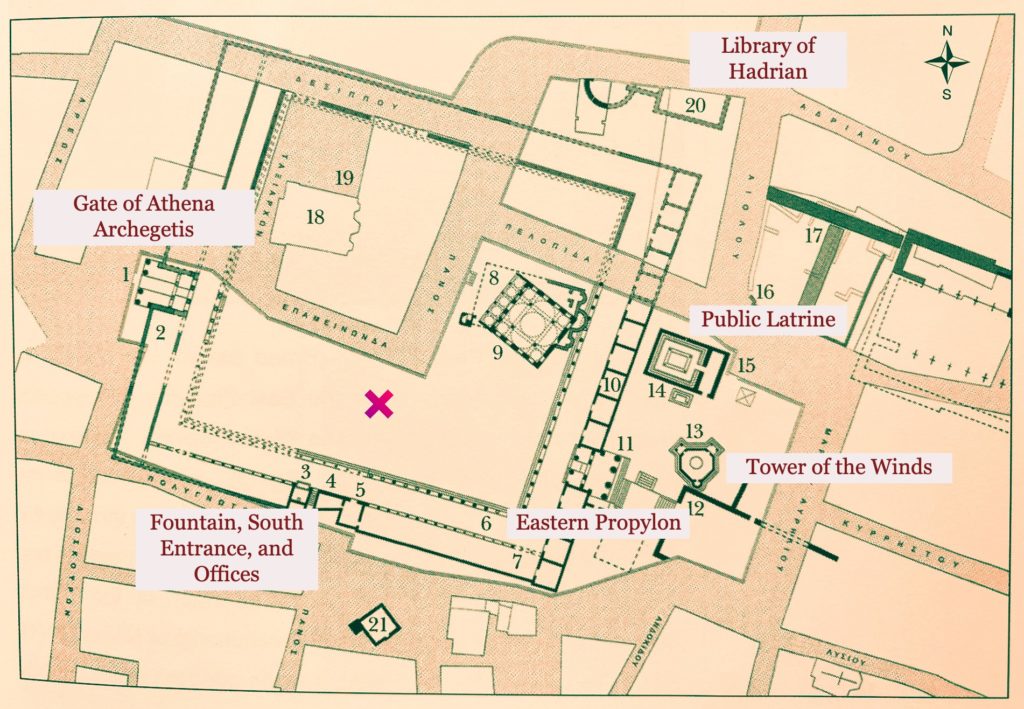

One of the most important additions made by Rome to the city of Athens was the Roman Agora or ‘Roman Forum’ built between 19-11 B.C.E by Augustus in fulfillment of a promise to the city by Julius Caesar.

This ‘new’ agora features largely in An Altar of Indignities, and is the site of a particularly riotous scene!

While the original ancient Agora of Athens remained an important focus of the city, it had become crowded with stoas, temples, and monuments to heroes and to the gods. There were fountains, a library, a mint, offices, altars, sanctuaries and more. But the first agora came to lack the great open space that allowed people to gather and trade with ease. The new, Roman Agora allowed for this.

Aerial photo of the Roman Agora of Athens with the gate of Athena Archegetis in the foreground

The Roman Agora of Athens consisted of a large paved, open-air courtyard that was surrounded by colonnades of white and grey marble from the surrounding mountains of Penteli and Hymettos. The colonnades were covered and had spaces for shops and merchants selling various goods, storerooms, the offices of the market, and a fountain. There was also an adjacent public latrine.

There were two propylaea, including the Gate of Athena Archegetis at the west end, and another propylon at the east end. Both entrances aligned with the ancient roads at either side.

The Tower of the Winds – the oldest meteorological station in the world

Just outside the eastern wall of the Roman Agora is a fascinating and unique Roman-era structure known as the Tower of the Winds.

The Tower of the Winds, built by Andronicus in the first century B.C.E, is said to be the oldest meteorological station in the world with sundials on the exterior, a hydraulic clock inside, and its bronze weather vane on top indicating the eight winds which is thought to have allowed merchants in the agora to know the winds and estimate the arrival of shipments coming from the port of Piraeus.

CLICK HERE to read our article on the Roman Agora of Athens and watch our full video tour of the archaeological site.

Emperor Hadrian (gold aureus)

There is one Roman ruler who looms very large in the history of Athens and that is Emperor Hadrian. Everywhere you go in the historic centre of the city, you are reminded of Hadrian. He loved Athens, and he loved to make things on an especially grand scale. Much of what he built in Athens is still visible today.

Beyond the walls of the Roman Agora are the remains of the great library built by Hadrian. Hadrian’s Library, as it is known, was built in 132 C.E. It was a large complex that served not only as a library, but also a cultural centre and public space that included lecture halls, a reading room, a vast courtyard and garden with a pool and, of course, the enormous bibliostasion where myriad precious scrolls were kept.

Today, you can visit the library by away of the monumental entrance near Monastiraki square, roam the gardens where mosaics are still open to the sky, and see the remaining walls of this magnificent piece off Athens’ cultural past.

The ‘Bibliostasion’ of the Library of Hadrian in Plaka, Athens

Southeast of the Acropolis are two more monuments to Hadrian’s generosity and love of grandeur. The one is the Arch of Hadrian which was built around 132 C.E. to honour the emperor. This gate, which one can walk up to today, marked the boundary between the ancient city of Athens and the new district built by Hadrian sometimes known as ‘Novae Athenae’ or ‘New Athens’.

Hadrian’s Gate

Just beyond the Arch of Hadrian, is perhaps one of the most impressive achievements of that emperor: the Temple of Olympian Zeus.

The Temple of Olympian Zeus, or the ‘Olympieion’ as it is known, was one of the largest temples ever built in the ancient world. Construction on it was begun as far back as the sixth century B.C.E under Peisistratos, but it was so ambitious that it was never finished.

Until Emperor Hadrian.

In 131 C.E., after over six hundred years, Emperor Hadrian finally completed the great Olympieion of Athens. The temple had a forest of 104 massive Corinthian columns and contained one of the largest cult statues of the ancient world.

The Temple of Olympian Zeus in Athens, as seen from the Acropolis

Today, only 15 of those magnificent columns remain standing. Nevertheless, this is a wonderful site to visit and the remains still give one a sense of the scale of this marvel of ancient architecture and great love that Emperor Hadrian had for Athens.

There is another Roman who features almost as largely as Hadrian in Athens’ past, and that is the wealthy Roman senator, Herodes Atticus. We will look at the man himself in a separate post in this series, but for now we will go over a few of the monuments he contributed to this ancient city.

The Panathenaic Stadium

The Panathenaic Stadium, or Kallimarmaro ( meaning ‘nice marble’), is one of the most recognizable monuments from ancient Athens, and it is still used to this day. It was originally built by Lycurgus in the fourth century B.C.E for the Panathenaea and is located in the small valley between the hills of Agras and Ardittos at the foot of the neighbourhood of Pangrati.

However, it was in about 144 C.E. that Herodes Atticus rebuilt the stadium in marble, after which it had a capacity of 50,000. This same stadium was excavated and restored in 1896 to host the first modern Olympic Games and is still used today for various Olympic ceremonies.

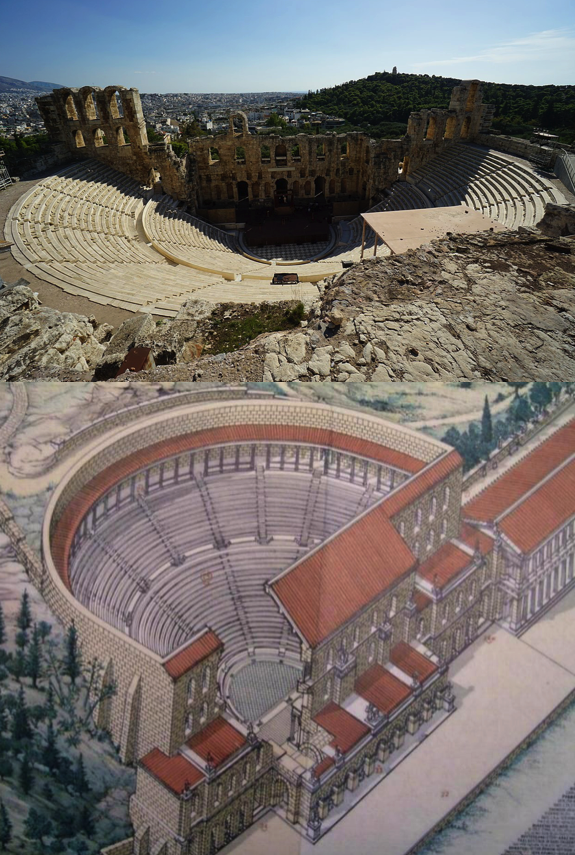

The Roman-era Odeon of Herodes Atticus, Athens

The monument for which Herodes Atticus is most famous in Athens is the one that bears his name: the Odeon of Herodes Atticus, or ‘The Herodeion’.

We will also take a close look at this amazing monument in a separate post in this blog series as it is central to the story of An Altar of Indignities. For now, the Odeon of Herodes Atticus was built around 161 C.E on the south slope of the Acropolis. It was a roofed odeon and served as a venue for concerts, theatrical performances and other public events. It remains in use to this day as a part of the annual Athens Epidaurus Festival, along with the great theatre of Epidaurus in the Peloponnese.

Philopappos Monument on the Hill of the Muses (Wikimedia Commons)

On the nearby Hill of the Muses, across the modern street from the Acropolis is another monument from the Roman period. It is known as the ‘Monument of Philopappos’. It was erected in around 114-116 C.E in honour of a Roman consul of Greek descent, Gaius Julius Antiochus Epiphanes Philopappos.

This grand monument that seems to jut out of the trees on the Hill of the Muses served as a mausoleum to this Roman-Greek consul, and is an indication of his importance to Athenian society at the time. Philopappos was said to have also been a poet and personal friend of Emperor Hadrian and Empress Vibia Sabina, making this yet another magnificent addition to the Hadrianic-period legacy of the city.

The Acropolis of Athens

When it comes to Athens, however, there is no monument greater, or more recognizable, than the Acropolis. This ‘high city’, crowned by the Temple of Athena Parthenos (the Parthenon) and other buildings and temples such as the Propylaea, the Erectheion, the Temple of Athena Nike, and the sanctuary of Artemis Brauronia, are all glorious reminders of Athens’ Archaic and Golden ages.

When it comes to the Roman period, much restoration of existing monuments was undertaken as structures had been damaged by time and war, not least Sulla’s siege of the Acropolis.

There were some monuments with statues that had been erected by foreign kings such as Attalos II of Pergamon (at the northwest corner of the Parthenon) and by Eumenes II in front of the Propylaea, the monumental entrance to the Acropolis plateau. These Hellenistic structures were later rededicated by Emperor Augustus and General Agrippa.

Recreation and present state of theT emple of Rome and Augustus on the Acropolis (Wikimedia Commons)

The only new, Roman addition to the Acropolis was that of the circular Temple of Rome and Augustus which was located about twenty-three meters from the Parthenon on the east side. This was constructed around 19 B.C.E to honour Rome and Emperor Augustus and was the last great construction to take place on the summit. This temple did not have a cella, as most temples did, but was more of an open air tholos (round temple) with a statue of Augustus beneath a roof supported by nine Ionic columns. Later, a metallic inscription was added to the temple to honour Emperor Nero, but this was later removed.

For a series of wonderful 3D recreations of Roman Athens, we highly recommend you visit the website for AncientAthens3D HERE.

Modern aerial view of the three harbours of the port of Piraeus, the port of Athens. The smaller harbours in the foreground are the ancient military harbours of Zea and Munichia. The commercial harbour of Kantharos is in the background.

Lastly, we cannot have a discussion of Roman monuments of Athens without mentioning the great port of Athens: Piraeus.

The port of Piraeus was made up of three harbours: the great commercial harbour of Kantharos (featured in An Altar of Indignities), and the smaller military harbours of Zea and Munichia.

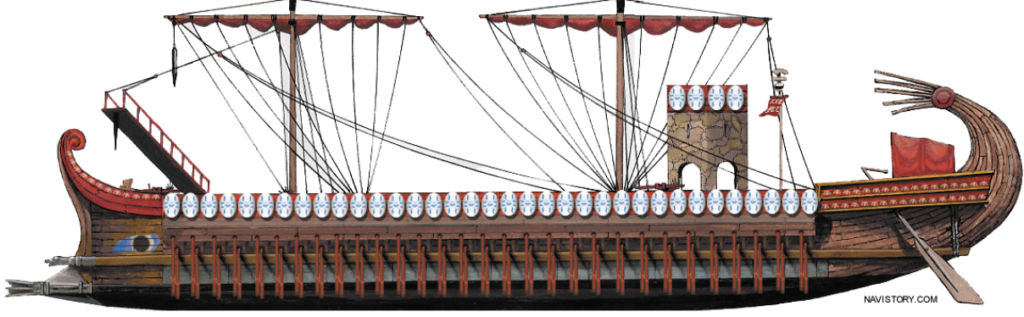

Piraeus has been an important naval and commercial hub for centuries and, in the Classical Greek and Roman periods, it was vital. When Greece came under Roman rule, much was done to improve the port of Piraeus as the Romans relied heavily upon it.

Infrastructure, such as docking facilities, warehouses and the road to Athens, were repaired, improved and expanded. This was for efficiency, but also to accommodate the larger Roman ships. The Romans are also believed to have improved the fortifications of Piraeus.

Recreation of a Roman Quadrireme (From the Naval Encyclopedia)

The Romans certainly knew the strategic value of Piraeus as it became a major naval base for the Roman fleet in the eastern Mediterranean which was often engaged in combatting the rampant piracy that took place in the region. Of course, as trade was central to the workings of the empire, there were customs offices operated by Rome to carry out the taxation of goods.

There were also some religious additions made by Rome to Piraeus, such as shrines to Jupiter and Neptune, which blended in with the existing shrines and temples to traditional Greek deities whom the Romans also respected.

These changes and more are an indication of the continued importance of Piraeus to Rome as a strategic maritime hub.

While the remains of Athens’ Golden Age continue to be the most glorious to behold, it is undeniable that Rome – despite the destruction it initially wrought on the city – more than made up for it with the monuments its emperors and well-to-do citizens constructed.

Today, Athens is among the most beautiful cities in the world, dotted with ancient monuments that are still marvels to see.

That said, Roman Athens in the early third century C.E., when our story takes place, must have been a wonder, something to rival the halls of Olympus itself.

If the Gods had a home on earth, Roman Athens must have been it.

Thank you for reading.

Artist impression of Roman Athens at its peak with the Ilissos River in the foreground and the Temple of Olympian Zeus centre-left.

There are more posts coming in The World of An Altar or Indignities, so make sure that you are subscribed to the Eagles and Dragons Publishing Newsletter so that you don’t miss any of them. When you subscribe you get the first prequel book in our #1 best-selling Eagles and Dragons series for FREE!

If you haven’t yet read any books in The Etrurian Players series, we highly recommend you begin with the multi award-winning first book Sincerity is a Goddess: A Dramatic and Romantic Comedy of Ancient Rome.

In celebration of drama in the ancient world, be sure to check out our ‘Ancient Theatre’ Collection in the Eagles and Dragons Publishing AGORA on Etsy which features a range of ancient theatre-themed clothing, glassware and more! CLICK HERE to browse.

An Altar of Indignities: A Dramatic and Romantic Comedy of Ancient Rome and Athens is now available in ebook, paperback and deluxe hardcover editions from all major online retailers, independent bookstores, brick and mortar chains, and your local public library.

CLICK HERE to buy a copy or get ISBN# information for the edition of your choice.

Brace yourselves! The Etrurian Players are back!

The World of An Altar of Indignities – Part I – Drama and Theatres in Ancient Athens

Greetings Readers, Hellenophiles, and Romanophiles!

Eagles and Dragons Publishing is proud to present an all new ‘World of’ blog series that will take a look at the research, people, and places related to the newest book in The Etrurian Players series, An Altar of Indignities: A Dramatic and Romantic Comedy of Ancient Rome and Athens.

We know that many of you are fans of these blog series connected with each of our book releases and we hope that you enjoy this one as much as those that have gone before.

In this newest series, we’ll be publishing a new article every two weeks or so on a wide range of relevant topics such as theatre, ancient Athens, festivals, religion, playwrights, customs and more.

And now, without further ado, let’s step into The World of An Altar of Indignities!

The Theatre of Epidaurus

In this first post, we’re going to be taking a brief look at drama and theatres in ancient Athens.

But this book is set during the Roman era, isn’t it? you might ask.

That is true, but the Romans were the inheritors and adopters of Greek theatrical traditions and, as the book is set in Roman Athens, we thought it would be good to start with a look at the birth of drama in ancient Greece.

Tragedy is an imitation of an action that is serious, complete, and of a certain magnitude…through pity and fear effecting the proper purgation of these emotions.

(Aristotle, Poetics)

In the West, we owe a great deal to the ancient Greeks, particularly the Athenians. Out of ancient Greece came epic poetry, and lyric poetry sung to music. There was elegiac poetry that expressed personal sentiments of love, lamentation, and military exhortations. Epigrams memorialized the dead in inscriptions across the Greek world. Iambic poetry relayed often satyrical ideas as close to natural speech as possible, and bucolic poetry in hexameter told stories of the lives of ordinary country people rather than of heroes.

There is much more to it, but you get the idea. Basically, all of our western literary traditions came out of Ancient Greece.

Not least among these genres was drama.

Relief of Maenads in ritualistic, frenzied dance honouring Dionysus.

The first thing we should look at is how the artform of ‘Drama’ came about as a form of entertainment.

Similar to gladiatorial combat in Ancient Rome, which began as a religious ritual for the dead, drama in Ancient Greece was born out of religious practices, in particular, rituals honouring the god, Dionysus.

Early worship to Dionysus involved a darker side with ecstatic worship by female followers – the maenads of mythology – who were said to partake in frenzied dances and tear into animal, and sometimes human, flesh. In the sixth century B.C.E the worship of Dionysus involved obscene play, extreme emotion, singing, and dancing.

This was the genesis of Greek drama.

It was the tyrant Peisistratos (c. 600-527 B.C.E) who founded the city Dionysia of Athens, the great festival in honour of Dionysus, which involved a chorus of men singing and dancing for the god. Later, there were also rural Dionysia about Attica, with similar rituals. These early choruses could be as large as fifty people, but most were believed to consist of twelve to fifteen members.

In the sixth century (c. 535 B.C.E), when a man named Thespis added himself to the ritual to deliver a prologue and interact with the Dionysian chorus, he is said to have become the very first actor, or ‘thespian’.

The addition of this one person to interact with the chorus is thought to be the beginning of true drama, the transition from religious ritual to dramatic performance for an audience.

Later, the playwright Aeschylus added a second actor and, after him, Sophocles added a third, and this became the standard number of actors for a while, in addition to the members of the chorus.

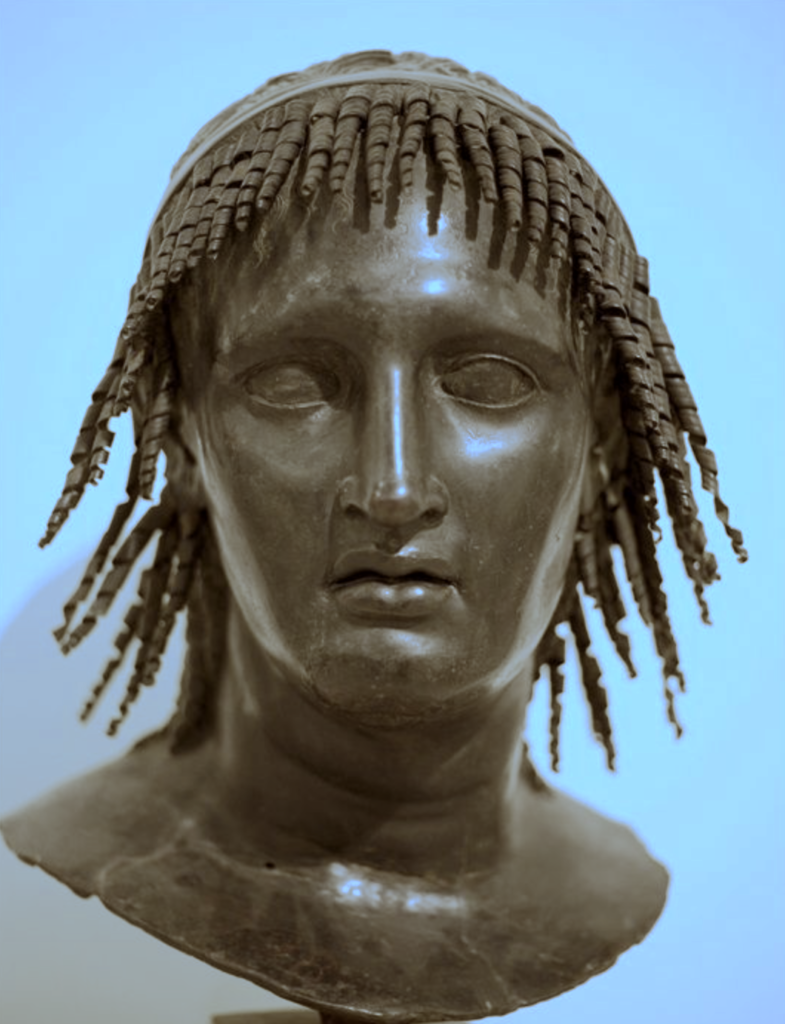

Roman bronze from Herculaneum thought to represent Thespis, the first actor.

In early drama, Greek comedies and tragedies were, more or less, musical productions. This was due to drama’s origins in dance and song for Dionysus. The members of the chorus played groups of people like the citizens of a city, dancing and singing.

These new dramas or plays, until the Hellenistic age, were performed in competitions as part of religious festivals like the Dionysia, the Lenaea (a winter festival to Dionysus), and the Panathenaea (to Athena Parthenos) at Athens. These theatre festivals were organized by the state.

For festivals, usually three poets were selected to have their work performed, and they were assigned an actor, or actors. The playwrights who participated wrote either tragedy or comedy, but not both. They usually submitted three tragedies on different themes and a satyr play, a short comedic piece (ex. Euripides’ Cyclops).

The winner of these competitions received a wreath. From about 499 B.C.E, the best actor also received a prize. All actors, even those playing female roles, were men. Oftentimes, the poets also acted in their own plays.

At Athens, when the Dionysia was in its infancy, the admission to watch the dramas was, apparently, about two obols. However, when Pericles was leading the way through Athens’ Golden Age, the state began to pay for admission to the theatre. In addition to male citizens, this sometimes also included non-citizens, or metics, as well as women and children who were, of course, accompanied by well-respected male citizens.

But before we get into the role that theatre played in Greek society, let’s first take a look at the types of drama that were performed, mainly Tragedy and Comedy.

It should be said at this point that, unfortunately, very little ancient drama has survived the centuries, and when it comes to tragedy, only Attic tragedies have survived.

Tragic dramas or plays from Ancient Greece seem to have originated in the mid-sixth century B.C.E in Attica or the Peloponnese, and the earliest surviving one we have is Aeschylus’ Persians (c. 472. B.C.E).

Ah! Miserable Fate! Black Fortune!

Black, unbearable, unexpected disaster!

A savage single-minded Fate has ravished the Persian race!

What troubles are still in store for me?

All strength has abandoned my body… my limbs… there is none left to face these elders.

Ah, Zeus! Why has this evil Fate not buried me, as well, send me to the underworld, among all my men?

(Aeschylus, Persians)

Tragedies were the first dramas and they were almost all based on mythological tales of gods, goddesses and heroes. They also had a standard format that comprised a prologos, sometimes presented by the chorus, and sometimes by an actor. Then there was a monologue or introduction. There was a parados, which was a song sung by the chorus as it entered. After that, there were various epeisodia, scenes with actors and the chorus, and during these epeisodia, stasima (songs) were performed. The play usually closed out with the exodos, the final scene or ‘exit’.

So, the first dramatic performances were tragedies and the genre gave rise to some of the most famous playwrights of the ancient world, including Aeschylus, Sophocles, and Euripides. However, tragedy began to decline by the end of the fourth century B.C.E in favour of comedy.

Melpomene – The Muse of Tragedy

The word comedy is derived from the Greek komoidia which comes from komos, a procession of singing and dancing revellers.

It is believed that comedy dates to the sixth century B.C.E and that it may have its roots in Sicilian or Megarian drama.

As with the tragedies, only Attic comedies survive to this day, and the earliest surviving one we have is Aristophanes’ Acharnians (c. 425 B.C.E). There were earlier comic poets such as Cratinus, Crates, Pherecrates, Eupolis and Plato (different to the famous philosopher), but none of their works survive.

Oh! by Bacchus! what a bouquet! It has the aroma of nectar and

ambrosia; this does not say to us, “Provision yourselves for three

days.” But it lisps the gentle numbers, “Go whither you will.”

I accept it, ratify it, drink it at one draught and consign the

Acharnians to limbo. Freed from the war and its ills, I shall

keep the Dionysia in the country.

(Aristophanes, Acharnians)

Ancient Greek comedy can be separated into three different types: Old Comedy, Middle Comedy, and New Comedy.

Comedies were humorous and uninhibited with many jokes about sex and excretions. They ridiculed and parodied contemporary characters, and an excellent example of this is Aristophanes’ ridiculing of Socrates in Clouds:

A bold rascal, a fine speaker, impudent, shameless, a braggart, and adept at stringing lies, and an old stager at quibbles, a complete table of laws, a thorough rattle, a fox to slip through any hole, supple as a leather strap, slippery as an eel, an artful fellow, a blusterer, a villain, a knave with one hundred faces, cunning, intolerable, a gluttonous dog.

(Aristophanes, Clouds)

Comedies also made fun of contemporary issues as well as gods, myths, and even religious ceremonies, making it a sort of acceptable outlet for mocking things that were otherwise sacred. This was a form of ‘free speech’ at work in the new Democracy of Athens.

All performances were staged during the city Dionysia and the Lenaea in Athens.

Old Comedy consisted of choral songs alternating with dialogue but it had less of a pattern than tragedy did. The chorus consisted of about twenty-four men and extras, and they often played animals. The actors wore grotesque costumes and masks.

Old comedies began with a prologos, and then the entrance of the chorus which proceeded to sing a parados, a song. Then there was the main event, the agon, a struggle, which was a debate or physical fight between two of the actors. There were songs during the action and subsequent scenes or epeisodia. The chorus also uttered a parabasis, which was a blessing on the audience. As with tragedy, comedies also ended with the final scene, or exodos.

Second century C.E. mosaic depicting dramatic masks for Tragedy and Comedy

Middle Comedy in Ancient Greece was basically Athenian comedy from about 400-323 B.C.E. It developed after the Peloponnesian War and was more experimental with different styles beginning to emerge. Apparently it became quite popular and experienced a revival in Sicily and Magna Graecia.

Comic choruses began to play less of a role, and the parabasis was no longer used. Interestingly, the more grotesque costumes and phalluses were not as popular either.

Comedic plots based on mythology and political satire began to give way to less harsh humour and a focus on ordinary lives and issues.

Sadly, no complete plays from Middle Comedy survive, but some of the authors we know of were Antiphanes, Tubules, Anaxandrides, Timocles, and Alexis. Some might also class Aristophanes as one of the earliest poets of Greek Middle Comedy.

Thalia – The Muse of Comedy

Lastly, New Comedy is generally considered to be Athenian comedy from the death of Alexander the Great in 323 B.C.E to about 263 B.C.E.

In New Comedy performances, plays were five acts long and were interspersed with unrelated choral or musical interludes. They were generally set in Athens or Attica, and the actors wore masks, but now dressed in regular everyday clothes.

Though new comedies were Athenian, writers came from around the broader Greek world to Athens to write, and to see the plays.

The themes of these new plays were more human and relatable and dealt with things such as family relationships, love, mistaken identities (a throw-over from Middle Comedy), the intrigues of slaves, and long-lost children.

There were also stock characters that emerged such as pimps and courtesans, soldiers, young men in love, genial old men, and angry old men.

The themes and characters of Greek New Comedy greatly influenced Roman drama and which became so popular for the Roman theatre crowd.

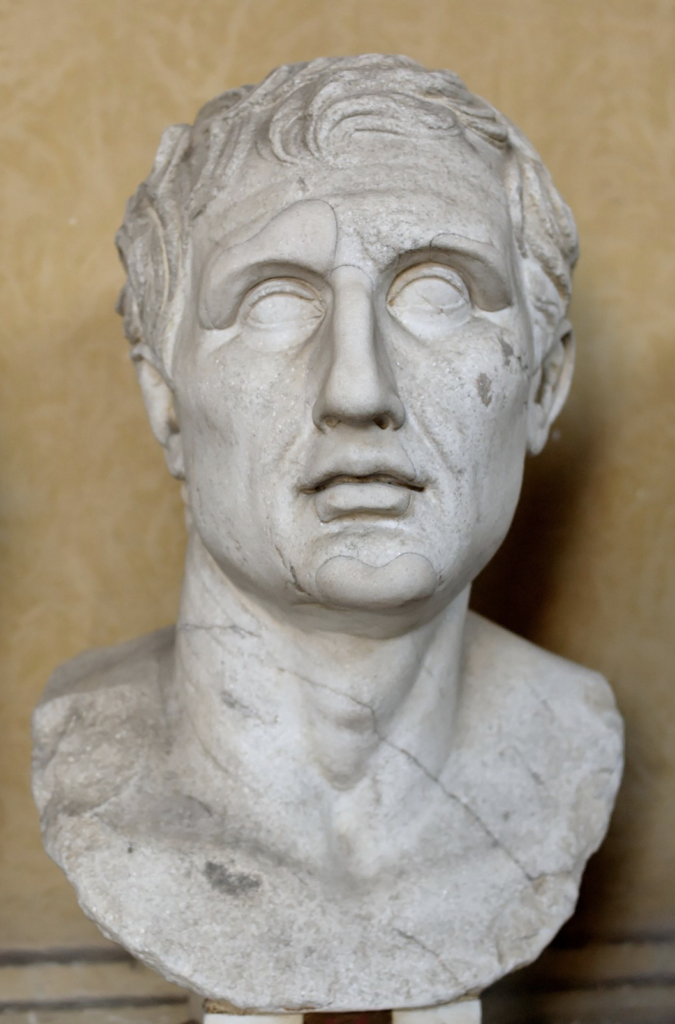

Menander (c. 343–291 B.C.E)

Sadly, little survives in the form of Greek New Comedy, but much Roman comedy such as plays by Plautus and Terence, were based on those Greek plays, particularly Menander (c. 341-290 B.C.E). Other authors included Diphilus and Philemon.

It is a true tragedy that so much comedy does not survive. Menander alone is thought to have written over one hundred plays, and yet only a small fragment of a single one of his plays survives.

Thankfully, Roman playwrights such as Plautus and Terence used Menander’s plays as blueprints for their own and, as a result of that New Comedy format and formula, they gave rise to the western comedic tradition we are familiar with to this day through Shakespeare, Moliere, and others.

Now that we have briefly touched on the history of drama and plays, let’s take a look at where these plays were actually performed.

The Theatre of Dionysus, Athens

The word ‘theatre’ comes from the Greek word theatron which literally means ‘a place for watching’.

Theatres were built from the sixth century B.C.E onward. Most religious sites had a theatre and, as previously mentioned, they were used to celebrate festivals in honour of Dionysus.

Greek drama grew out of these religious festivals.

Early theatres could be temporary wooden structures, or a sort of scaffolding, but this practice was ceased after a deadly collapse in the Agora of Athens in about 497 B.C.E. After that, performances in Athens moved to the hillside where the theatre of Dionysus was built on the south slope of the Acropolis.

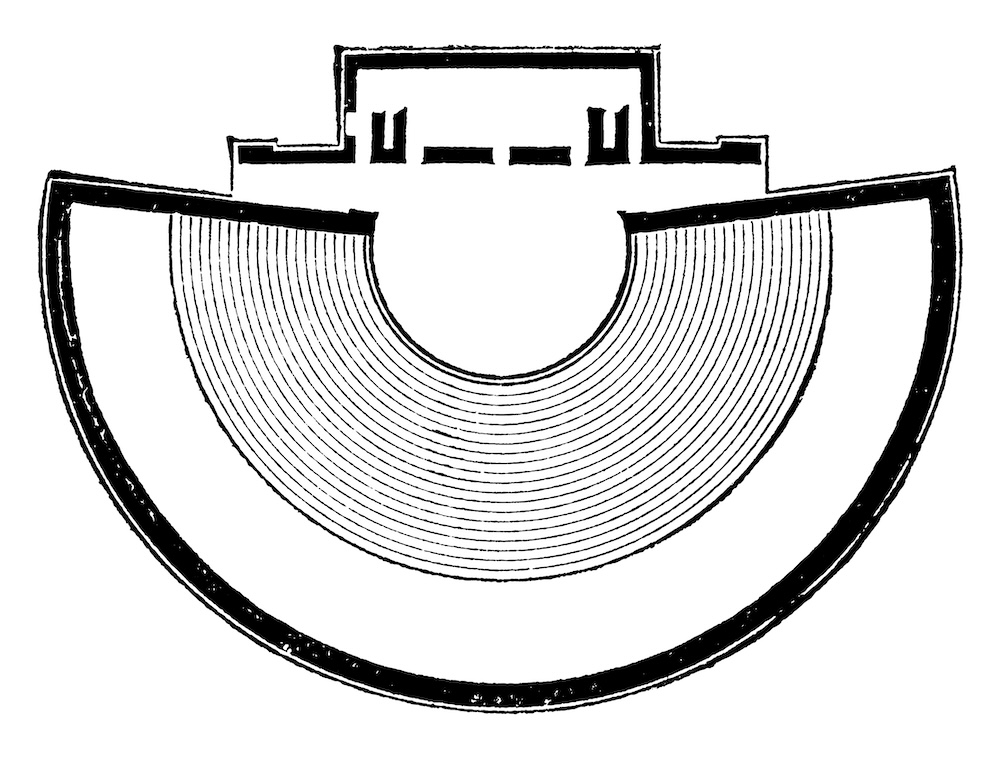

It became common practice to build theatres into the slopes or hillsides of natural hollows or, alternatively, into man-made embankments which supported tiers of seats on the hillside. Beginning in the fourth century B.C.E, theatre seating was built in marble. Theatres were generally D-shaped or on half-circle plans.

Ground Plan of the Ionian Greek theatre at Iassos.

All theatres where drama was performed were ‘open-air’ and had several common components: the koilon (the seating area) where the seats in the front row were reserved for priests and officials, the orkestra (the circular performance space), and the skene (a building for storage and changing rooms for actors). Later, the skene became a stage with a backdrop called the proskenion (in Latin, the scaena frons). The addition of this stage (pulpitum in Latin) expanded the performance area.

The other common performance space that was similar to theatres in Ancient Greece was the odeon (plur. odeia). These were usually roofed structures for listening to musical recitals and contests, poetry readings and other similar performances. Odeia were basically small theatres with a roof.

The first odeon of ancient Athens is thought to be that built by Pericles in the fifth century B.C.E. It was located directly beside the theatre of Dionysus and was a pyramidal structure made of wood with the roof supported by many columns. Some believe it was designed to resemble the tent of the defeated King of Persia.

Other odeia of ancient Athens included the Odeon of Agrippa in the Athenian Agora, and the stunning Odeon of Herodes Atticus on the southwestern slope of the Acropolis which is still used for performances to this day and which is featured in An Altar of Indignities.

Acropolis of Athens with the Odeon of Herodes Atticus before it on the left.

Today, theatre and dramatic performance is seen as more of a luxury in western society, something for the privileged few.

This was not the case in ancient Athens.

Though drama had religious beginnings, it evolved into an important way for Greeks as a society (albeit mostly for male citizens) to investigate the world in which they lived and what it meant to be human.

Aristotle believed that drama, tragedy in particular, had a way of cleansing the heart through pity and terror. It could purge men of their petty concerns and worries and, with this noble ‘suffering’, they underwent a sort of catharsis.

With the advent of philosophical thought, theatre and drama became the vehicle that encouraged average Greeks to become more ‘moral’ by helping them to process the issues of the day through both Tragedy and Comedy.

Rather than being a leisure activity for the elites, as it is perceived today, attending the theatre in ancient Athens was an important form of civic engagement after exercising one’s rights and performing one’s duties for the community (such as voting). Watching and experiencing tragedies and comedies with one’s fellow citizens became an important activity in the new Democracy of the day.

Not only did the drama and theatres of ancient Athens inspire their Roman successors, they also helped to shape the artistic traditions of western civilization.

For that, we should all be grateful.

Thank you for reading.

An array of Greek theatre masks

We hope that you’ve enjoyed this short post on drama and theatres in ancient Athens. There is a lot more to learn on this subject. We highly recommend the documentary series by Professor Michael Scott, Ancient Greece: The Greatest Show on Earth. You can watch the first episode HERE.

You can also read our popular articles on Theatres in Ancient Rome and Drama and Actors in Ancient Rome.

There are a lot more posts coming in The World of An Altar or Indignities, so make sure that you are subscribed to the Eagles and Dragons Publishing Newsletter so that you don’t miss any of them. When you subscribe you get the first book in our #1 best-selling Eagles and Dragons series for FREE!

If you haven’t yet read any books in The Etrurian Players series, we highly recommend you begin with the multi award-winning first book Sincerity is a Goddess: A Dramatic and Romantic Comedy of Ancient Rome.

In celebration of drama in the ancient world, be sure to check out our ‘Ancient Theatre’ Collection in the Eagles and Dragons Publishing AGORA on Etsy which features a range of ancient theatre-themed clothing, glassware and more! CLICK HERE to browse.

Stay tuned for the next post in this blog series in which we’ll be looking at travel and transportation in the Roman Empire.

An Altar of Indignities: A Dramatic and Romantic Comedy of Ancient Rome and Athens is now available in ebook, paperback and deluxe hardcover editions from all major online retailers, independent bookstores, brick and mortar chains, and your local public library.

CLICK HERE to buy a copy or get ISBN# information for the edition of your choice.

Brace yourselves! The Etrurian Players are back!

New Release! – The Etrurian Players are Back!

Greetings Readers and History-Lovers!

Eagles and Dragons Publishing is thrilled to announce the release of Book II in The Etrurian Players series!

The title is An Altar of Indignities: A Dramatic and Romantic Comedy of Ancient Rome and Athens and it is an embarrassing and touching story of family and friendship, creativity, and the discomfort that humans experience as life inevitably changes.

The story takes place in the Roman Empire in the year 205 CE…

Brace yourselves! The Etrurian Players are back!

The Gods are well aware that mortals have a habit of taking themselves far too seriously. This is especially true of The Etrurian Players, the greatest theatrical troupe in the Roman Empire.

Basking in the glories of their resounding success in Rome, Felix Modestus and his players find themselves on the sacred island of Delos when Apollo decides it is time to check Felix’s growing hubris with a new and potentially deadly mission: he must show the people of Athens that Romans are just as capable of theatrical greatness as the Greeks!

Faced with this titanic task, Felix once again enlists the help of his oldest friends, Rufio and Clara, who travel from their farm in Etruria to Athens for the great Panathenaic festival when the precarious production is destined to take place.

As the company attempts to prepare for the performance, their efforts are constantly hampered by haughty critics, a rival theatre troupe, wailing children, wild animals, and the pleasures of Athena’s polis.

Will The Etrurian Players overcome distraction to win over the people of Athens? Will they survive the trials and judgement of Apollo? Or will they succumb to the humiliation and self-doubt that lurks around every creative corner?

Only by believing in themselves and helping each other can they survive and prove once again that The Etrurian Players are worthy of praise and the Gods’ favour.

If you like dramatic and comic stories about wild artists, persistent shades, and unbelievable episodes with goats, monkeys, and dogs, then you will howl and cry at An Altar of Indignities!

Read this book today for a theatrical misadventure in Roman Athens that will leave you asking the Gods ‘What were they thinking?’.

If you haven’t yet experienced The Etrurian Players series, be sure to check out Book I first, the multi award-winning title, Sincerity is a Goddess: A Dramatic and Romantic Comedy of Ancient Rome.

If you are feeling down about the world at the moment, The Etrurian Players series is just the ticket you need to feel good and know that there is indeed hope for us all!

An Altar of Indignities is now available in ebook, paperback and deluxe hardcover editions from all major online retailers, independent bookstores, brick and mortar chains, and your local public library.

CLICK HERE to buy a copy or get ISBN# information for the edition of your choice.

You can also purchase the ebook directly from Eagles and Dragons Publishing by clicking HERE.

We’re so excited to share this dramatic and romantic comedy with the world, and we’re thrilled that you’re joining us on the adventure!

Thank you for reading!

Nemea – The Myth and Place

There is one race of men, one race of gods; and from a single mother we both draw our breath. But all allotted power divides us: man is nothing, but for the gods the bronze sky endures as a secure home forever. Nevertheless, we bear some resemblance to the immortals, either in greatness of mind or in nature, although we do not know, by day or by night, towards what goal fortune has written that we should run…

(Pindar, Nemean Ode #6)

For those who love history and archaeology, travelling through Greece is an absolute joy. There is something around every corner, bend in the road, mountain top or valley. History, and its remains, are everywhere.

For me, however, the thing I like the most about this ancient land is how history and mythology are so closely linked, and how they are indelibly tied to the landscape itself.

The Peloponnese is especially rich in this way.

It would take a whole lifetime to visit every historical and archaeological site and landscape that has strong links to the stories of myth and legend from Ancient Greece.

This past summer, we returned to one such place, and I was reminded of how rich and deeply moving this connection between myth, history, and the land can be.

This place is Ancient Nemea.

I first visited Nemea almost twenty years ago, just prior to the 2004 Athens Olympics. At the time, I was unfamiliar with the history and mythology of the site. I was more caught up with this gathering of mysterious ruins set among the undulating vineyards of Nemea’s Wine Country, the largest wine region in Greece where the variety is sometimes known as the ‘Blood of Herakles’.

The myths are as much a part of the Agiorgitiko wine as are the fragrant aromas of raspberry or cherry.

Returning to the site in 2023, I explored the site with a great deal more knowledge of what I was looking at, but also with an awareness of the poignant reason for the creation of the site and the Nemean Games, one of the four Crown Games of Ancient Greece, which were held here.

First, a bit about the myths…

Perhaps the most famous myth related to Nemea is in relation to the first labour of Herakles in which the hero defeated the Nemean Lion. It’s a fantastic and exciting myth, but the Nemean Games were not started in honour of Herakles’ great labour.

In legend, the Nemean Games are related to the ‘Seven Against Thebes’, the group of warriors who went with Polynices to take back Thebes from his brother, Eteocles. On their way to Thebes, the Seven stopped in Nemea where King Lykourgos ruled with his queen, Eurydike.

The king and queen had a newborn son named Opheltes, whom they were told by the Oracle at Delphi that they could not let touch the ground until he could walk.

However, one day, the baby’s nurse, Hypsipyle, was walking with the baby when the Seven stopped in Nemea. The Seven asked where the nearest well was, and so Hypsipyle put the baby Opheltes down on a bed of wild celery while she took the generals to the well.

The baby was set upon the ground in contradiction of the Oracle of Delphi’s warning, and so a snake came along and killed the child.

The Seven saw this as a bad omen and sought to honour the soul of the slain child, and propitiate the Gods by holding funeral games on site.

Thus were the Nemean Games born as funeral games for the deceased child, Opheltes.

The victory crown for the Nemean Games, was a crown of wild celery.

The slaying of the Opheltes by the serpent

The first historical games at Nemea were held in 573 B.C., and they took place every two years. There was no settlement at Nemea, and the games were most often under the auspices of Argos, moving to that ancient city to the south for long stretches of time, except during the period of Macedonian hegemony.

The sanctuary at Nemea was important in the ancient world, but somehow experienced more neglect than others when the Games were moved to Argos. Pausanias, in his second century A.D. tour of Greece, describes the run-down ruins of the site during the Roman period:

In Nemea there is a temple of Zeus Nemeios worth visiting, although the roof has collapsed and there is no longer any statue. Around the temple is a sacred cypress grove. Here was Opheltes, put on the grass by his wet-nurse, killed by the snake, according to the story. The inhabitants of Argos sacrifice to Zeus also in Nemea and choose a priest of Zeus Nemeios. They organize a running contest for men in armour at the festival of the Winter Nemea. So there is the grave of Opheltes, with a stone enclosure around it and inside the enclosure altars. There is also a tumulus as a monument for Lykourgos, the father of Opheltes.

(Pausanias II 15, 2-3)

The Temple of Zeus at Nemea with the great Altar of Zeus in the foreground

Unlike the sanctuary at Ancient Olympia, the archaeological site of Nemea is quiet and uncrowded. You can roam at will where you like without running into any other tourists. It is almost a meditation to visit this place, and that’s good, for the air is heavy with tragedy and toil, and the songs of victory.

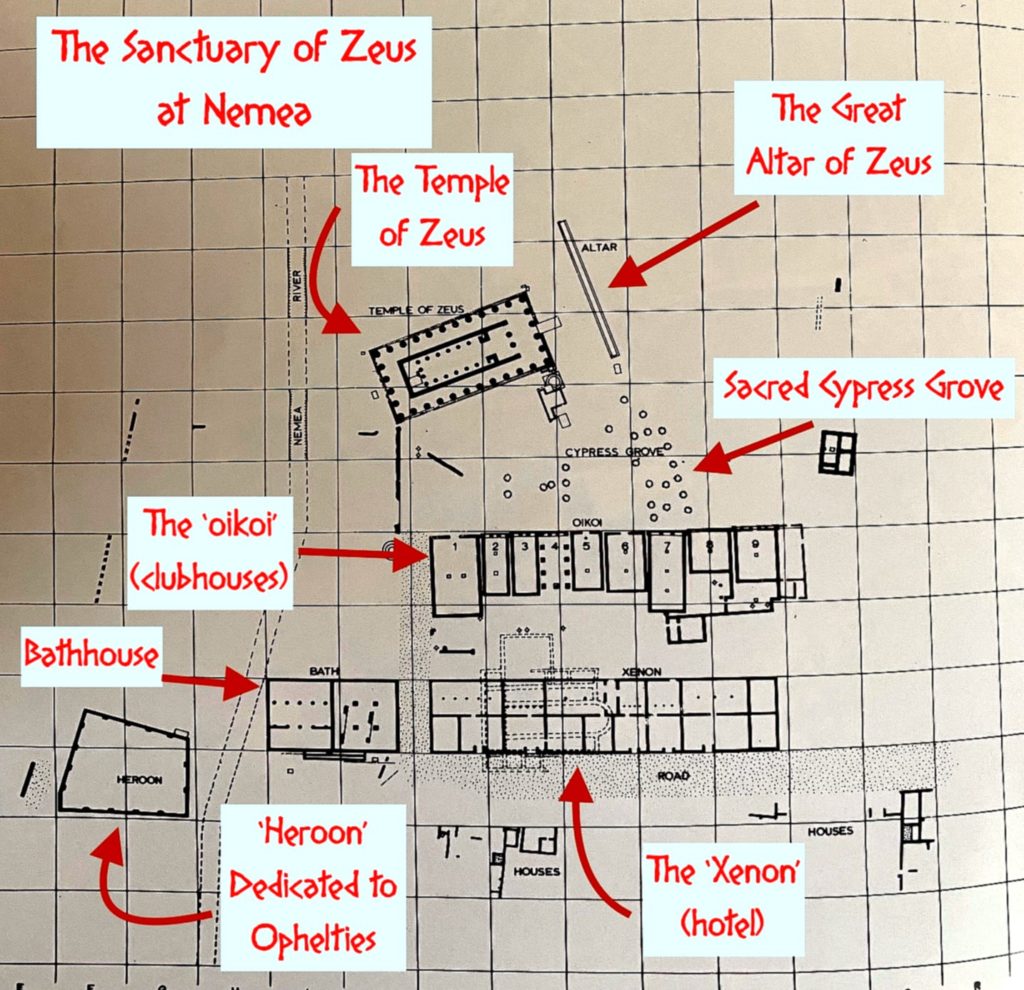

The archaeological site is actually two different sites: the Sanctuary of Zeus, and the Ancient Stadium.

The main site, the Sanctuary of Zeus, where the wonderful museum is located, includes the remains of houses, baths, and a hero shrine or heroon dedicated to the child, Opheltes. It also includes the ruins of the xenon, a sort of ancient hotel for visitors or participants in the Games, and a series of nine oikoi, or ‘clubhouses’ sponsored by specific city-states to house their athletes and coaches during the Games.

The most impressive part of the Nemean sanctuary, however, is the temple of Nemean Zeus which was built c.330 B.C.

The lovingly restored ruins of this temple are truly inspiring and, unlike other sites such as the Parthenon, you can walk through the temple to get a better sense of its scale and its magic. Uniquely, the temple contains the remains of a sunken crypt accessed through the cella, or inner chamber. It is believed the crypt was either used as the site of an oracle, or as a treasury for the sanctuary.

On the east side of the temple is another feature that is unique to Nemea, and Isthmia (an altar to Poseidon), and that is a very long altar to Zeus where athletes and trainers swore their oaths and made sacrifices prior to the competitions. This altar dates to the fifth century B.C.

When we visited the site this time, we were armed with a 4K video camera and so, rather than tell you about all the minute details of the sanctuary, we can now show you in the video Nemea – A Tour of the Sanctuary of Zeus…

After roaming the Sanctuary of Zeus, we got in the car and drove the very short distance down the road to the second part of the archaeological site of Ancient Nemea, the Stadium.

This site is much smaller than the sanctuary, taking less time to visit, but it is well worth it.

Participants in the Nemean Games would have sworn their oaths and made their offerings to Zeus at the long altar in the sanctuary before processing to the stadium for the actual athletic competitions.

Nemea’s stadium is smaller than Olympia’s, but it’s still substantial, as it should have been for a location of one of the four Crown Games. It could seat up to 40,000 spectators in its day on the roughly hewn stone seats and embankments.

There are some fascinating remains to be seen at Nemea’s stadium, including the starting line and its mechanism, as well as the channels that flow around the stadium, once fed by mountain springs, so that athletes and spectators could drink and stay hydrated during the competitions.

The apodyterion, or ‘locker room’ where athletes prepared

Perhaps the most fascinating parts of the stadium, however, are the remains of the apodyterion, or ‘locker room’, and the barrel-vaulted tunnel which led from there to the stadium. One can still see the graffiti carved by waiting athletes on the stone walls of the tunnel.

When you visit this site, you can walk everywhere at will, including on the stadium floor, and then on a path high on the treed embankments for a magnificent view of the stadium and surrounding countryside.

Even more so than the massive stadium at Ancient Olympia, the stadium at Nemea really does give one a sense of the competitions and sacred games that took place here. And for those of you who want to deepen your experience of the Nemean Games, you can participate for yourselves in the modern, revived Nemean Games which are actually taking place in the summer of 2024! CLICK HERE for more information!

Once again, we visited this amazing archaeological site with our video camera in hand. You can take a full virtual tour of the stadium in Nemea – A Tour of the Ancient Stadium…

I firmly believe that it is well worth revisiting sites such as Ancient Nemea, for as the years go by, as we experience more of this life, as we learn more, our new perspectives allow us to see such places in a different light.

For me, Ancient Nemea is one such place.

If you ever get the chance to visit, I highly recommend it.

Who would have thought that so much could come out of the death of a small child? Then again, tragedy and glory are interwoven in the myths and places of Ancient Greece.

Thank you for reading.

If you are interested in visiting Ancient Nemea for yourself, be sure to check out the deals that are available from Eagles and Dragons Publishing’s subsidiary, Ancient World Travel here: https://www.ancientworldtravel.net/travel-resources-1

Check out our specially-curated deals on visits, tours and tickets to Ancient Nemea, and Nemean Wine Tours at the following link:

https://viator.tp.st/V9XO4E5D

Also, read the review of La Petite Planète in the nearby village of Mycenae which is a great place to spend the night:

https://www.ancientworldtravel.net/post/hotel-review-la-petite-planète-a-warm-welcome-in-the-shadow-of-ancient-mycenae

Victory for Heart of Fire!

Eagles and Dragons Publishing has some big news to share today!

As many of you know, 2024 is an Olympic year, and so it is fitting that today we share some wonderful news about Heart of Fire: A Novel of the Ancient Olympics.

First of all, The Historical Fiction Company (HFC) recently awarded Heart of Fire Five Stars and the ‘Highly Recommended’ Award of Excellence.

As the HFC one of the premier reviewers of historical fiction in the world, this is indeed an honour that we are all proud of.

In addition to the award, the HFC’s editorial review of Heart of Fire rendered us speechless with extremely high praise for the story, for Adam’s knowledge and storytelling abilities, and for our amazing editor at Beautiful Ink Editing whose work is “top-notch, making for a smooth reading experience.”

Below are some excerpts from The Historical Fiction Company’s review of Heart of Fire…

“…Haviaras grabs the reader’s interest right away with an engaging and evocative opening. The first sentence immediately immerses the reader in antiquity and establishes the epic tale’s setting. This intriguing hook reveals the author’s skill in drawing readers in from the beginning of the narrative.

In Heart of Fire, Adam Alexander Haviaras transports us to the vibrant heart of ancient Greece through a story that is both a realistic recreation of the ancient Olympic Games and a voyage of personal salvation. Haviaras is an engrossing, poignant story that is full of the essence of human struggle and victory through the perspective of Kyniska, a Spartan princess with dreams of Olympic glory, and Stefanos, an Argive mercenary with a turbulent background.

Heart of Fire brings the most famous athletic event in ancient history to serve as the backdrop for a brilliant fusion of romance, mythology, and history. The plot is intriguing, drawing us in with a blend of deep personal stakes and wider historical ramifications. Haviaras explores what it means to pursue glory and redemption in a civilization constrained by strict conventions and long-standing rivalries via the weaving of a tale of love, honor, and ambition…

… The next strong suit of the book is the character development. It’s very well done and we’re able to relate to Stefanos and Kyniska’s challenges and goals because of the nuanced and intricate writing. Stefanos has a fascinating and complex path from a violent existence to one filled with honor and purpose. Kyniska defies the norms of her era and epitomizes strength and resolve. Their growth throughout the book is evidence of Haviaras’ talent for developing believable and incredibly inspirational characters.

The plot keeps up a smooth flow, with each chapter adding to the story’s increasing energy. Haviaras skillfully strikes a balance between the personal and historical aspects, allowing the story to flow naturally toward its conclusion. Heart of Fire’s continuity is a crucial component that keeps you interested and ready to find out what happens to the characters.”

Green olive wreath on white. Top view

“Another positive of this book is the uniqueness. Heart of Fire is notable for how differently it portrays the historical Olympic Games. Haviaras provides a novel viewpoint on a well-known historical era by contrasting the grandeur of the Olympics with the intimate tales of its protagonists. The novel’s examination of concepts like love, competition, and atonement via the prisms of athletics and combat brings a noteworthy level of uniqueness…

…Heart of Fire‘s narrative arc is expertly written, following a precise path that heightens suspense and expectation. The story moves along at a good clip, striking a pleasing mix of action and emotional nuance from Stefanos’ early search for atonement to the pivotal events of the Olympic Games. The storyline comes to a dramatic climax that not only settles the main problems but also has a long- lasting effect on the reader.

With vivid descriptions and real dialogue, Haviaras’ writing eloquently and precisely captures the spirit of Ancient Greece. The author’s skill in fusing vivid storytelling with historical detail is astounding, resulting in an engaging and educational story. Heart of Fire is an excellent example of Haviaras’ storytelling ability and his in-depth knowledge of antiquity.

Heart of Fire ends in a way that is both thought-provoking and satisfying. The conclusion, which will not give away any plot points, sums up the themes of sacrifice and triumph and leaves readers with a strong impression of the characters’ travels. For anyone who has ever dared to dream large, it is a fitting conclusion to the novel’s examination of reaching greatness despite all circumstances.

In summary, Adam Alexander Haviaras’ Heart of Fire: A Novel of the Ancient Olympics is a magnificent story that vividly and emotionally captures the world of ancient Greece. Haviaras explores the ageless human search for greatness and significance via the connected destiny of Kyniska and Stefanos, as well as the spirit of the ancient Olympics. For those who enjoy historical fiction as well as those who are enthralled with Ancient Greece and its lasting influence, this book is a must-read.”

We’re thrilled by this wonderful award and the amazing review which The Historical Fiction Company has bestowed on Adam and Heart of Fire.

To read the full review on The Historical Fiction Company’s website, CLICK HERE.

If you are looking for an exciting summer read in this year of the Olympiad, then look no further than Heart of Fire: A Novel of the Ancient Olympics!

Heart of Fire is available in e-book, paperback and special edition hardcover from all major online retailers, independent bookstores, brick and mortar chains, and your local public library.

CLICK HERE to buy a copy or get ISBN# information for the edition of your choice.

Remember… There can be no victory without sacrifice.

The Tombs of Mycenae

Greetings History and Mythology-Lovers!

We are heading back to Mycenae in this post to explore the domiciles of the Dead outside the walls of the ancient citadel, that is, the great tombs of Mycenae.

In our previous post, we walked through the entire fortress of Mycenae, discussed what it was like and how it felt to return to that ancient and, some would say, menacing, fortress after twenty years.

To read the previous post, Return to Mycenae, CLICK HERE.

Likewise, to go on a full tour of the archaeological site, check out our video Mycenae: A Tour of the Ancient Citadel, HERE.

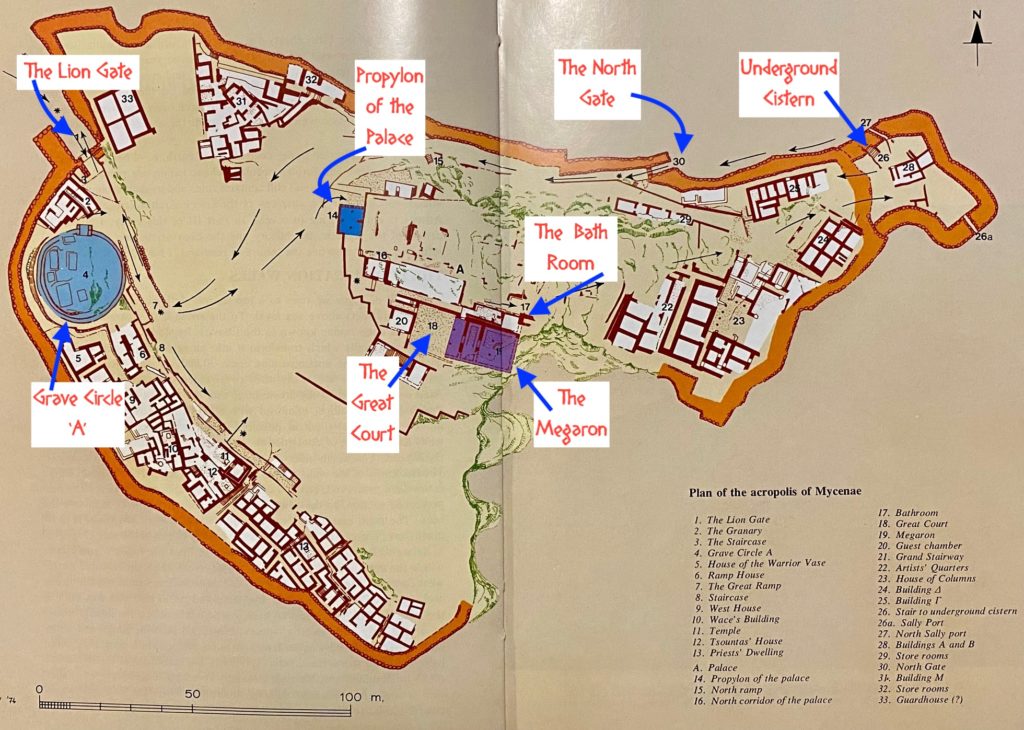

Grave Circle ‘A’ within the walls of Mycenae’s citadel.

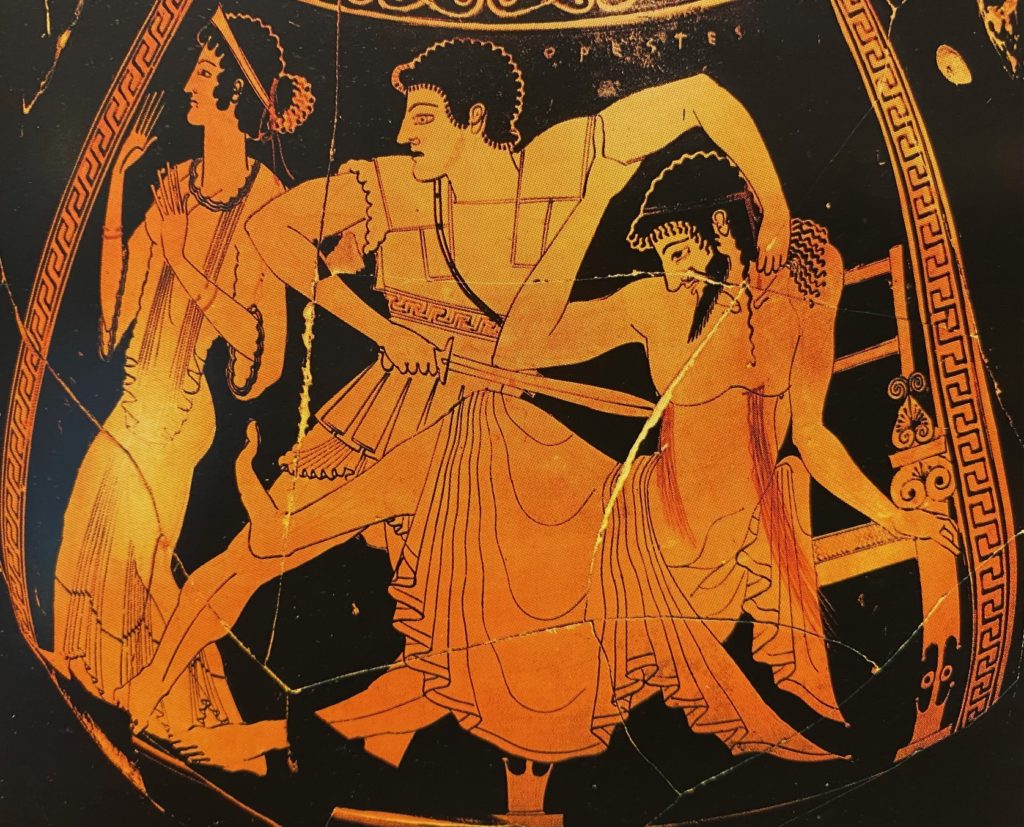

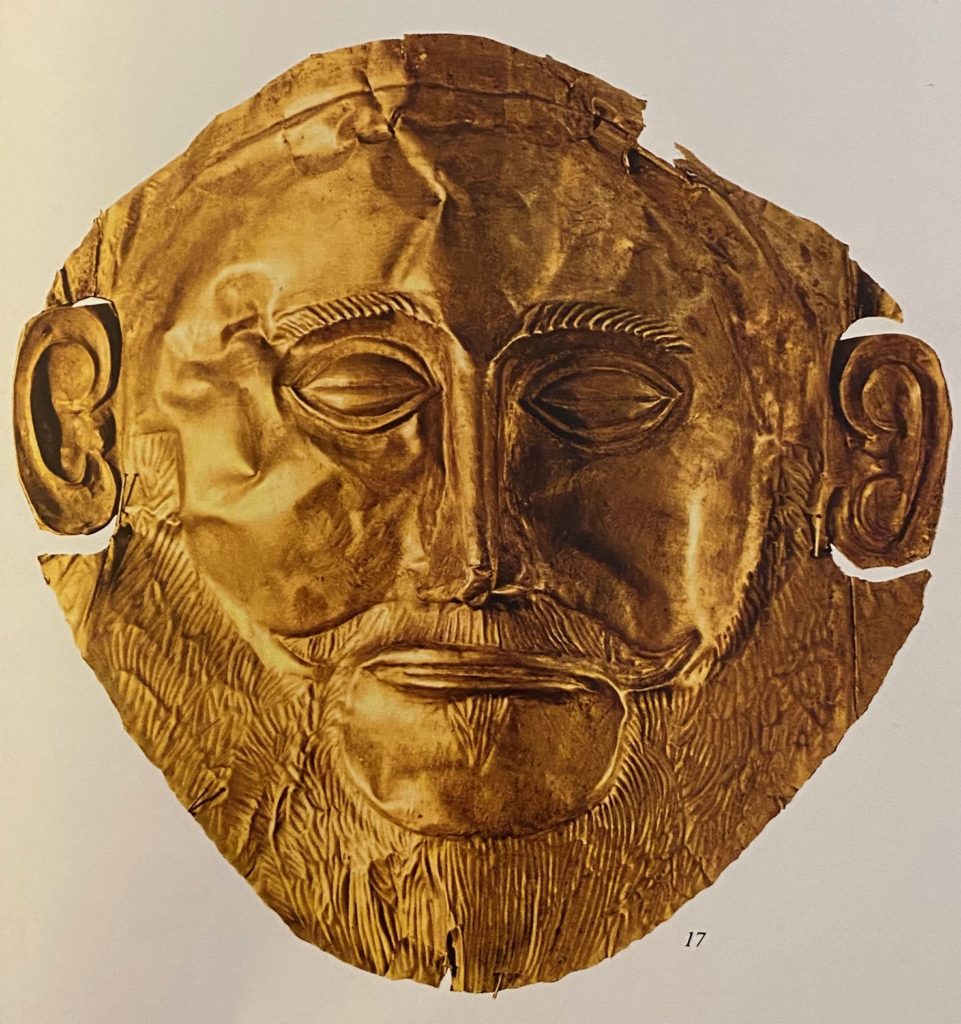

In our tour of the fortress, and the video, we explored what is known as ‘Grave Circle A’ which is located within the walls of Mycenae and was the location of the royal cemetery. It was here that graves pre-dating the Trojan War were located, and where many of the magnificent finds of Mycenae were discovered, including the golden death mask Heinrich Schliemann mistakenly took to be the ‘Face of Agamemnon’.

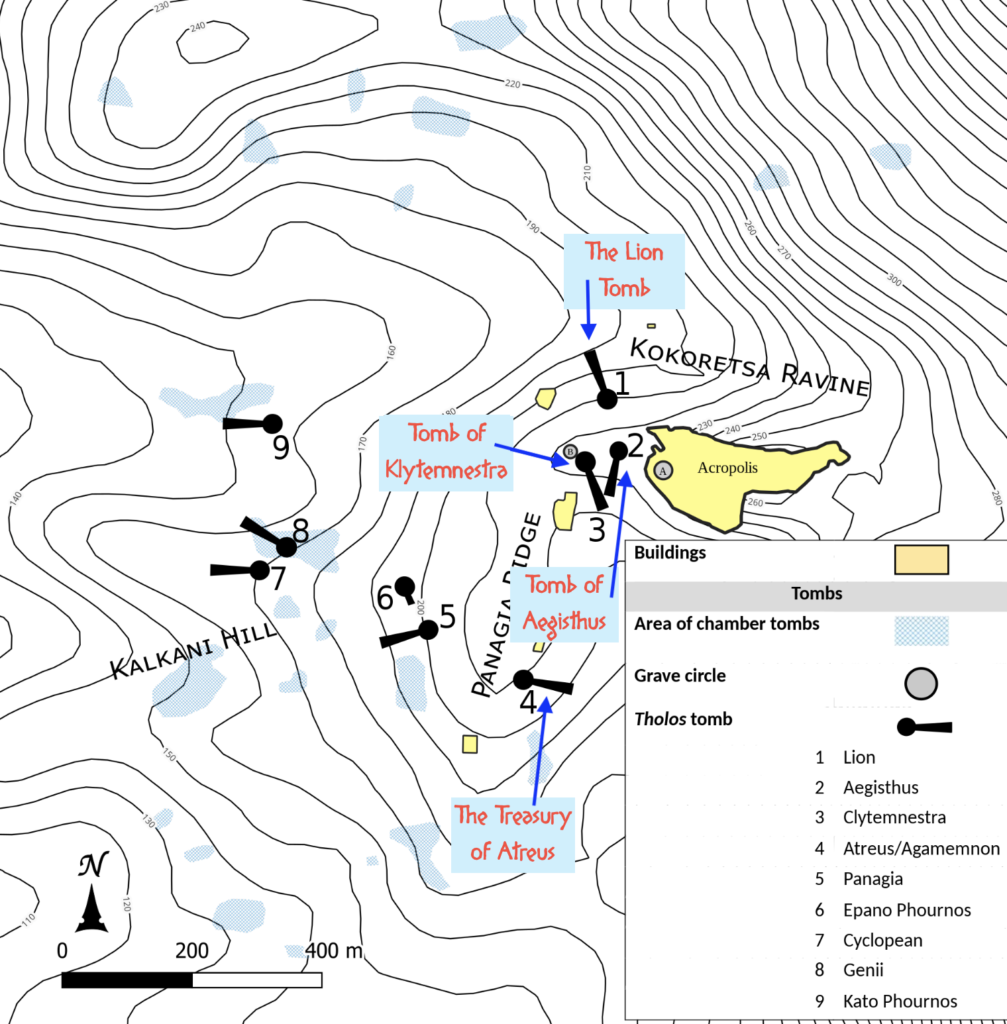

In this post, we are going outside the fortress walls of Mycenae to explore four of the most astonishing tombs of the Greek Bronze Age: the Lion Tomb, the Tomb of Aegisthus, the Tomb of Klytemnestra, and of course, the Treasury of Atreus.

But first, let us take a brief look at the types of tombs these represented.

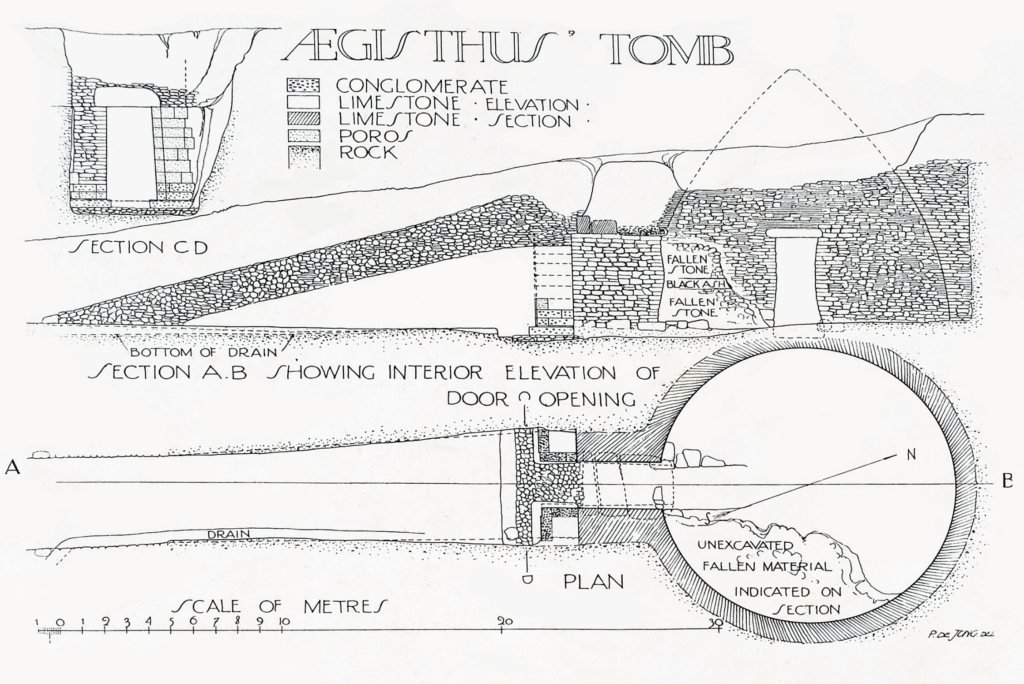

Parts of a Mycenaean chamber tomb, drawn up by Piet de Jong in 1920–1923

The graves located within ‘Grave Circle A’ are what are known as ‘shaft graves’ and, within the citadel, these were used to bury royalty with their astounding grave goods.

The tombs which we are looking at here are known as ‘chamber tombs’, of which there are many in the hills about Mycenae. These consisted of rock-cut chambers underground which were achieved by way of a passage called the dromos, which means ‘road’.

These chamber tombs could vary in size and shape, but when it came to the royal chamber tombs, or ‘beehive tombs’, they were meant to impress!

Artist representation of a Mycenaean tholos or ‘beehive’ tomb

The royal beehive tombs outside the walls of Mycenae were built into the hillsides and approached each by a long dromos, the largest being thirty-seven meters in length!

They had elaborate doorways and entranceways known as the stomion, beyond which are the vast, round burial chambers. These beehive tombs were roofed by a stone vault of horizontal rings which diminished in diameter until the roof closed at the top. They were true feats of engineering at the time. They were also referred to as tholos tombs because of their round shape. In some cases, such as the Lion Tomb, rectangular cists were cut into the floors of these tombs to accommodate bodies and valuable grave goods.

At Mycenae, there are approximately nine tholos or ‘beehive’ tombs that are known to date, dating from roughly around 1550 B.C.E to the end of the 13th century B.C.E.

Unfortunately, the grave robbers had cleaned all of them out, but the tombs themselves remained largely intact, and we are going to explore four of them today.

Map of Tombs at Mycenae

There is the grave of Atreus, along with the graves of such as returned with Agamemnon from Troy, and were murdered by Aegisthus after he had given them a banquet… Klytemnestra and Aegisthus were buried at some little distance from the wall. They were thought unworthy of a place within it, where lay Agamemnon himself and those who were murdered with him.

(Pausanias, Description of Greece, 2.16)

In his ‘Description of Greece’, the second century C.E. traveller and historian, Pausanias, makes mention of the tombs outside of the fortress walls, and three of them were on our list to visit after we finished our long, hot journey through the ruins of the fortress that dominated the area.

When we came out of the Lion Gate of Mycenae, cutting our way through the army of invading tourists, we turned left immediately and followed the dirt path down to where we knew there were two of the tombs we wanted to see.

Over twenty years ago, when we were last in Mycenae, these had been closed to the public because of their state of disrepair and the risk of stone falling upon one’s head. However, this time, we were thrilled to discover that these first two tombs, the tombs of Aegisthus and of Klytemnestra, were open!

Entrance to the ‘Tomb of Aegisthus’

The Tomb of Aegisthus was the first into which we ventured. It is the smaller tomb, and seemed to have born the brunt of time as much of the beehive roof was missing, leaving its golden sandstone walls open to sky. The chamber of this is still an impressive thirteen meters wide and the dromos is twenty-two meters long and five meters wide.

What struck me about this tomb – aside from the fact that this grand house of the dead may have been built for the murderer of Agamemnon – was the size of the lintel above the deep entrance.

There was a scaffold beneath this, supporting the entrance, which forced us to look carefully as we walked beneath and into the sun-drenched inner chamber.

The interior of the ‘Tomb of Aegisthus’ viewed from above with the plain of Argos in the distance.

When we emerged from the Tomb of Aegisthus, we turned right and went a short distance downhill to the site of the Tomb of Klytemnestra, King Agamemnon’s queen, and the mother of Electra and Orestes.

I would be lying if I didn’t note that I felt strange approaching the supposed tomb of this legendary character of Greek legend. Yes, Klytemnestra was said to be an adulterer with Aegisthus, but she was also daughter of King Tyndareus of Sparta, the older half-sister of the famed Helen, a jilted wife, and a tragically vengeful mother whose daughter was sacrificed by her husband.

I felt for the tragic, yet powerful spirit of Klytemnestra as I approached her final resting place.

The ‘Tomb of Klytemnestra’

The Tomb of Klytemnestra is thought to be the latest in date at Mycenae, constructed around 1220 B.C.E. The dromos of the tomb is thirty-seven meters long and six meters wide, and is lined with massive rectangular blocks.

The triangle over the lintel and the rest of the entrance would have been faced with marble slabs that were covered with elaborate carvings of spirals, rosettes and more, and the stromion seems to have contained a great wooden door about midway through its depth.

When we entered the Tomb of Klytemnestra, it was dark and sad, a feeling that was no doubt added to by what looked like a dead body at a glance, but which turned out to be a sad stray dog come to cool itself from the 45+ Celsius degree day.

The chamber of this tomb is only slightly larger that that of Aegisthus’ at thirteen and a half meters, but the beehive vault is fully intact and disappears into the darkness thirteen meters overhead.

This truly is an impressive monument and well-worth the visit if you have the strength after visiting the citadel. To be able to see even more, consider bringing a good flashlight the better to view the stonework inside.

Interior of the ‘Tomb of Klytemnestra’

After the Tomb of Klytemnestra, we climbed back up the hill toward the Lion Gate and then down toward the site museum.

To our surprise, there was yet another tholos tomb to the left of the museum. Without delay, we went down the rocky slope to its dromos, delighted to find that no one else was there.

Entrance to ‘The Lion Tomb’ of Mycenae

The ‘Lion Tomb’ is thus named because of its proximity to the famed ‘Lion Gate’ of Mycenae’s citadel. This is believed to have been constructed some time in the middle of the fourteenth century B.C.E. and has a dromos that is twenty-two meters long and almost five-and-a-half meters wide.

Sadly, the roof of this tomb is no longer intact, but it is estimated that its dome soared to a height of fifteen meters. It is still an impressive work, the chamber of which is fourteen meters wide and contained three pit graves which were found to be empty upon its discovery.

We stood in the middle of this chamber, our voices carrying around the bright, poros stone, and marvelled at its beauty, wondered who had been buried here. Had they been warriors of Mycenae, or members of the royal family who were not fit to be buried within the citadel, as Pausanias points out was the case for Klytemnestra and Aegisthus?

We will never know, but it certainly felt like a gift to be there with no one else around.

Interior of ‘The Lion Tomb’

From the Lion Tomb, we made our way to the museum to view many of the wonderful artifacts discovered at Mycenae. It is worth a visit, if anything to cool off from the Greek summer heat. The most important finds from Mycenae, including the golden death masks and bronze daggers, can be seen at the National Archaeological Museum in Athens, which everyone should visit.

After a refreshing, and overpriced, cup of freshly squeezed Argive orange juice in the parking lot, we got in our car and bid farewell to Mycenae’s walls.

But not before one final stop.

A short distance down the road to the modern village of Mykines, you will find on the right the entrance to the great ‘Treasury of Atreus’, or, as the locals have called it in the past, the ‘Tomb of Agamemnon’.

The Treasury of Atreus is accessed by way of a separate entrance to the main archaeological site, but it is no less impressive.

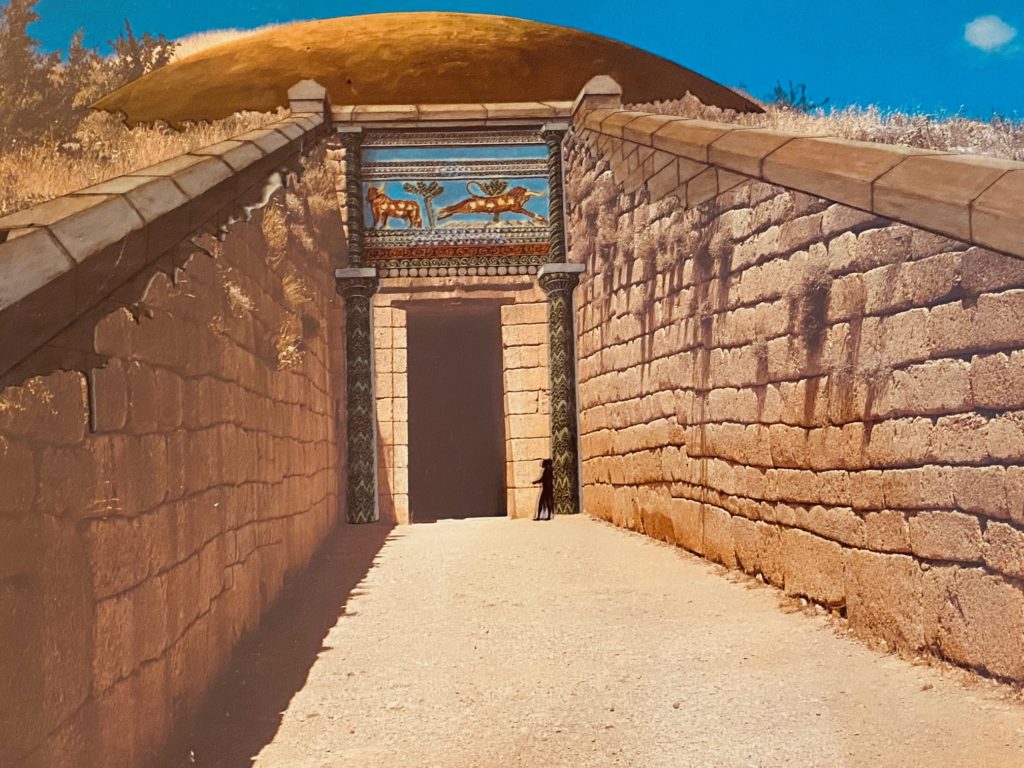

Artist impression of the ‘Treasury of Atreus’

The Treasury of Atreus – named for the legendary son of Pelops and Hippodameia, and father of King Agamemnon, and King Menelaus of Sparta – is one of the most impressive monuments of the Mycenaean Age. It is completely preserved with only the decoration of the facade and interior missing.

Approaching the tomb, one is filled with a sense of awe and wonder. Who was truly buried here, and why did their people believe they deserved such a monument? What was the burial ceremony like, and what magnificent grave goods were interred with the dead, only to be stolen by grave robbers to disappear for all time?

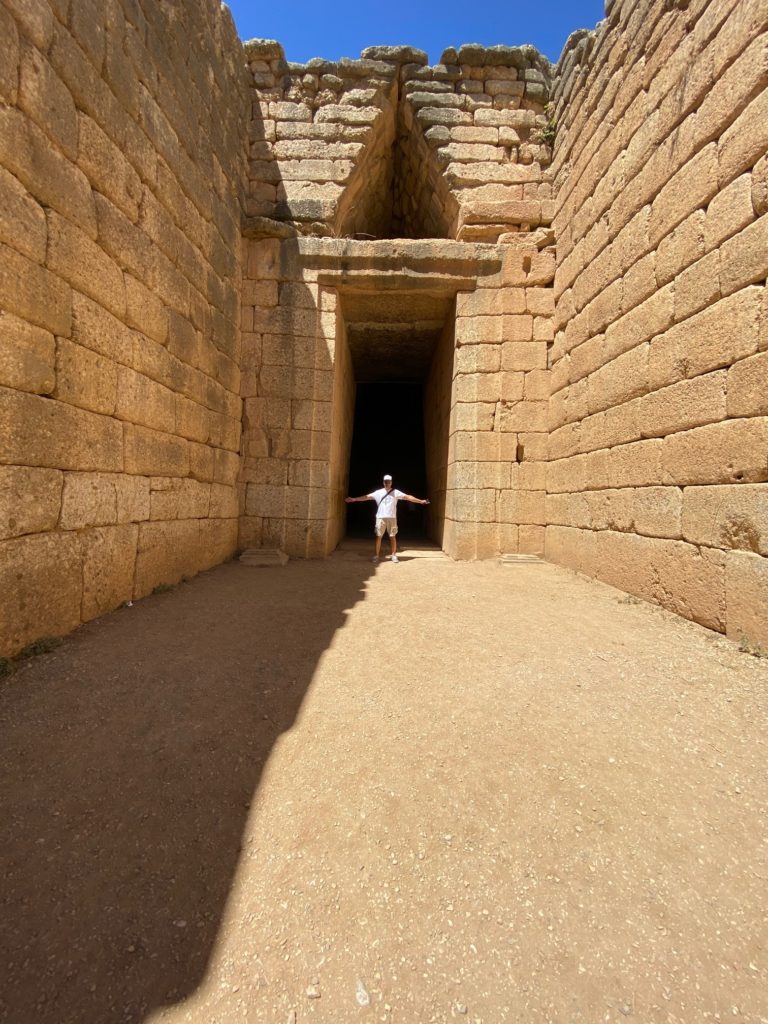

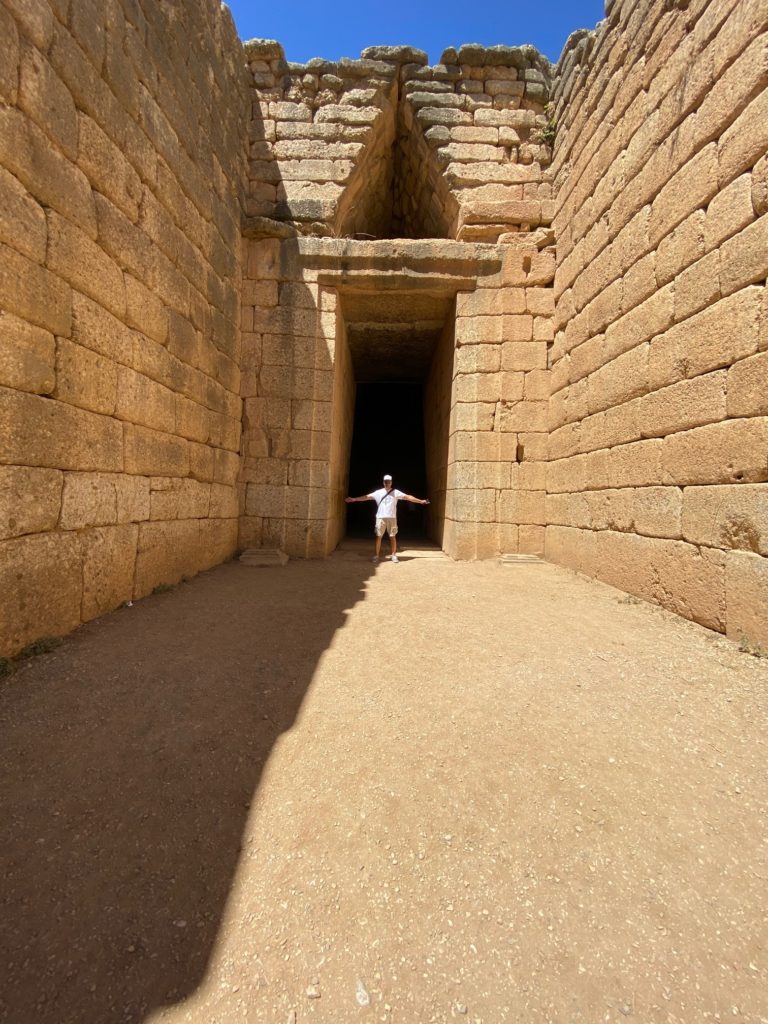

Standing in front of the Treasury of Atreus

The dromos leading to the tomb is cut into the rock of the hillside and is lined with massive rectangular blocks. It is thirty-six meters long and six meters wide, and the height of the entrance to the tomb is a stunning ten and a half meters high. The actually doorway measures just under five-and-a-half meters high and nearly three meters wide.

Passing beneath the lintel and the gaping triangle that would have been faced with ornate columns of green stone and a fresco or sculpture is an eerie experience. Remains of these can be seen in the National Archaeological Museum in Athens.

As we walked from the blistering heat and sunlight into the cool darkness of the tomb, it was indeed like stepping into another world, a world of the Dead.

Though there were many tourists by the time we reached the Treasury of Atreus, their presence seemed to be swallowed up by the tomb’s darkness, allowing us to observe our surroundings in relative peace.

Ceiling of the ‘Treasury of Atreus’

The main chamber of the tomb measures just over fourteen-and-a-half meters in diameter. It is a broad space one steps into upon entering the tomb, but the first thing that really draws the eye is the soaring ceiling of the tomb’s mesmerizing beehive construction.

The ceiling reached to a height of about thirteen-and-a-half meters high with thirty-three courses, or ‘rings’, of perfectly joined stones making up the construction. It is a true feat of engineering, that much is obvious, but it was also ornate, a home fit for kings in the Afterlife, though the ornamentation that would have decorated the circular walls is all gone, stolen since long before the visit of Pausanias in the second century C.E.

It is not only incredible to think that this tomb may have held the remains for such legendary figures as Atreus or Agamemnon but also, perhaps more so, it is stunning that it is still intact. The construction of this tomb has survived since the thirteenth century B.C.E.

The ante-chamber within the ‘Treasury of Atreus’

One feature that sets this particular Mycenaean chamber tomb apart from the others is the addition of an ante-chamber within the tomb. This large room is located to the right as one enters the treasury and was another burial chamber, in addition to the main chamber. The ante-chamber is blocked off and is deep and dark, but if you have a flashlight handy you can just make out the interior.

Once we finished explored the tomb, the air growing somewhat heavy within, we bid farewell to the shades of Atreus and Agamemnon, and made our way to the doorway and the light outside in the land of the living.

The tomb’s maw spat us out and we shielded our eyes as we walked in the sliver of shade offered by the walls of the dromos. It was time to leave Mycenae and the dead behind but, just as Orpheus could not help but turn to seek Eurydice at the gates of the Underworld, we also felt the need to turn around for one final glance at the magnificent entrance of the Treasury of Atreus.

The light outside the ‘Treasury of Atreus’

If you ever go to Mycenae, after exploring the citadel itself, be sure to leave time to visit the tombs of Mycenae, those great houses of the Dead that surround it.

They are some of the most stunning pieces of Mycenaean architecture that you will ever see, and when you emerge from them, from the deep darkness into the light, those tombs, and the shades of their inhabitants, will leave a lasting impression.

The ‘Lion Gate’ of Mycenae

If you are interested in visiting Mycenae for yourself, be sure to check out the deals that are available from Eagles and Dragons Publishing’s subsidiary, Ancient World Travel here:

https://www.ancientworldtravel.net/travel-resources-1

Check out our specially-curated deals on visits, tours (many from Athens) and tickets to Ancient Mycenae at the following link:

https://viator.tp.st/4DfkV2n1

Also, read the review of La Petite Planète, a lovely hotel (with an amazing terrace for dinner!) in the village of Mycenae where you can stay here:

https://www.ancientworldtravel.net/post/hotel-review-la-petite-planète-a-warm-welcome-in-the-shadow-of-ancient-mycenae

Lastly, check out the new video tour, The Tombs of Mycenae, on the Eagles and Dragons Publishing YouTube and Rumble channels.

Come with us as we explore the interior of these magnificent tombs of the Mycenaean age!

Thank you for watching, and thank you for reading!

Return to Mycenae

Mycenae…

The name conjures something deep inside, something out of myth and legend. There is a feeling of mystery about the name, of power, and perhaps of dread.

How is that? It’s just a name after all, isn’t it?

Not really. It’s much more than that.

Mycenae.

It echoes in the mind, in the memory of time. For me, it is something of a sign post in far away antiquity. It’s not just a place, but also a culture, a people… It is a warlike period that stands out in the vast Bronze Age, between the Age of Heroes and the Archaic period.

Mycenae itself, the place, is a symbol of a brutal time, long ago, that continues to captivate our imaginations, the same way that it has done for our ancestors since then.

Mycenaean Warriors

A barrage of names comes to mind when I think of Mycenae, like so many barbed bronze arrows raining down in the midst of a battle – Atreus, Agamemnon, Achilles, Menelaus, Helen, Clytemnestra, Electra, Orestes and all the heroes of the Trojan War. I think of Homer whose epic Iliada immortalized them all, and even of Alexander the Great who is said to have slept with a copy of that epic beneath his pillow.

Before the summer of 2023, the last time I had visited Mycenae, that dread cyclopean-walled palace whose corridors echoed with war and murder, was on a warm day in March over twenty-years ago.

On my first visit, it was springtime, the ruins surrounded by wild flowers.

I had been back to Greece frequently since then, of course, visiting other archaeological sites, writing about them in my novels and articles, but in all that time, I avoided Mycenae.

I don’t know why exactly, but my natural tendency was to give it a wide berth, to be near it, but only orbiting it. I avoided the tourist assault upon the great ‘Lion Gate’, and the blazing heat that one experiences when visiting it in high summer.

I felt like returning to Mycenae too soon was like returning to the scene of a crime. There is a lingering sadness, a sense of loss about the place that is difficult to describe.

As the epics teach us, however, life is beautiful, and terrible, and fleeting. Since my first visit long ago, time seemed to have flowed more quickly than I would have wished when I as a child.

The citadel of Mycenae as seen from the approach on the road from the modern village of Mykines.

When I first visited Mycenae I was much younger, a little naive, and definitely more idealistic. I was just setting out for my own battles beneath the walls of a distant, metaphorical Troy.

Older now, and having endured my own toils, I wondered if I was ready to return to the flattened halls of Mycenae with a perspective that is afforded by age and experience.

With my wife, and our own children bearing the same excitement and idealism I once possessed, the decision was taken. We would make our way to Mycenae.

Aerial view of the archaeological site

Though it is mostly known as the fortress of King Agamemnon, who led the Greek army at Troy, Mycenae has a long, rich and mythical past.

Briefly then…

Although it is believed that there has been habitation on the acropolis of Mycenae since roughly c. 2500 B.C.E, legend has it that Mycenae was originally founded by Perseus, the son of Zeus and Danae, and first King of Mycenae. Perseus is said to have used the legendary Cyclops to build Mycenae’s great walls some time in the first half of the 14th century B.C.E.

For a long time, Mycenae thrived under the descendants of Perseus, including Eurystheus for whom Herakles performed his famed Labours. After Eurystheus was killed in battle against the children of Herakles and the Athenians, the people of Mycenae chose Atreus, the son of Pelops and Hippodameia to rule them.

Many years of prosperity and greatness followed under the Atreidai dynasty, beginning with King Atreus, and then under his son, King Agamemnon, who was said to be the greatest king in Greece, ruling over the plains of Argos to the south, and the entire northeastern Peloponnese, including Corinth, sometime between 1220-1190.

Mycenae was at the heart of this world, and one of the most important cultural and political centres during Greece’s Bronze Age until its destruction toward the end of the 12th century B.C.E.

It was (and remains) a place where the history of the curse of the Atreidai, written about by ancient playwrights, still echoes about the landscape, and behind the mass of Mycenae’s great Cyclopean walls.

Ajax, Agamemnon, and Odysseus

The later traveller Pausanias, who visited Mycenae in the middle of the second century C.E. is thought to be the last ancient author to write about Mycenae:

There still remain, however, parts of the city wall, including the gate, upon which stand lions. These, too, are said to be the work of the Cyclopes, who made for Proetus the wall at Tiryns.

In the ruins of Mycenae is a fountain called Persea; there are also underground chambers of Atreus and his children, in which were stored their treasures. There is the grave of Atreus, along with the graves of such as returned with Agamemnon from Troy, and were murdered by Aegisthus after he had given them a banquet. As for the tomb of Cassandra, it is claimed by the Lacedaemonians who dwell around Amyclae. Agamemnon has his tomb, and so has Eurymedon the charioteer, while another is shared by Teledamus and Pelops, twin sons, they say, of Cassandra, whom while yet babies Aegisthus slew after their parents. Electra has her tomb, for Orestes married her to Pylades. Hellanicus adds that the children of Pylades by Electra were Medon and Strophius. Clytemnestra and Aegisthus were buried at some little distance from the wall. They were thought unworthy of a place within it, where lay Agamemnon himself and those who were murdered with him.

(Pausanias, Description of Greece, 2.16)

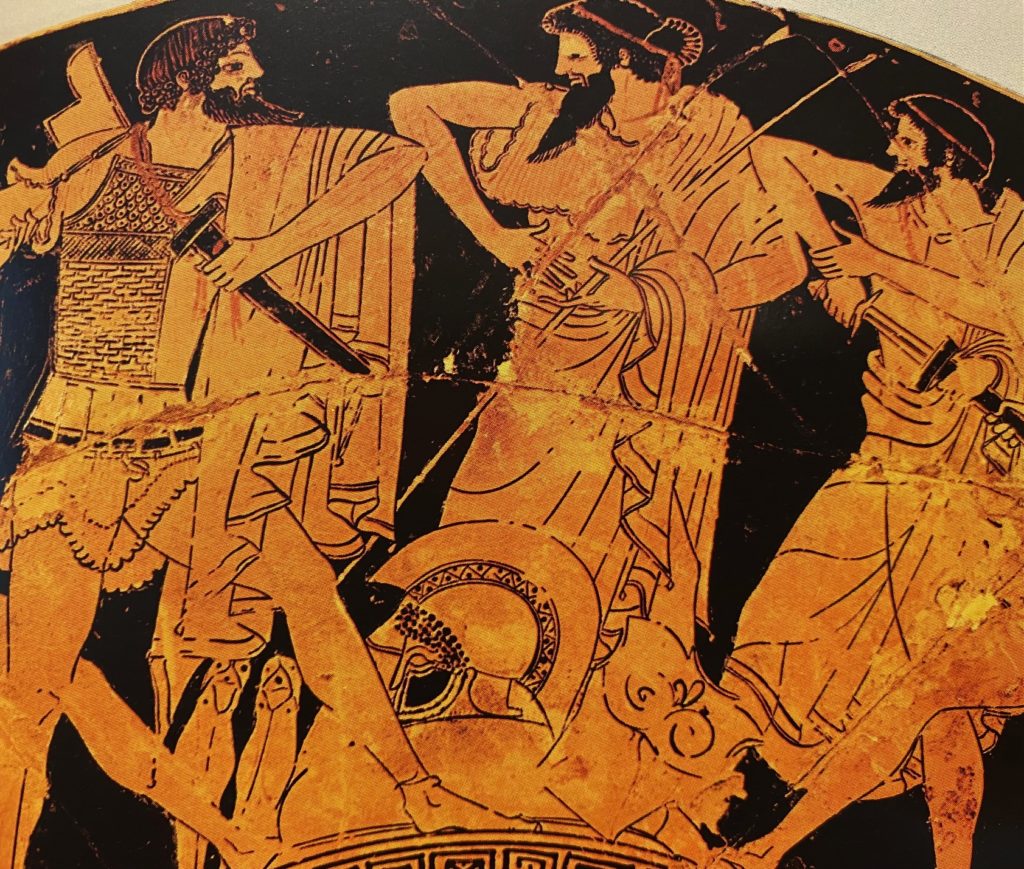

The Murder of Aegisthus by Orestes

When we made the decision to visit Mycenae again, these are the stories and people whom I was thinking about the night before as we ate dinner on a terrace beneath the stars.

The night was hot and calm, those ancient mountains black against the purple and indigo night sky pocked with stars. From our hotel in the modern village of Mykines, I was constantly aware of the citadel up the hill, surrounded by the tombs of legends. As I sipped cool wine from a glass and listened to the bark of a distant dog, or the screech of a fox, I wondered if, from the palace of Mycenae itself, Agamemnon and Clytemnestra, Orestes and Electra, or even a young Iphigenia, had seen what I was seeing.

Had those people of myth and legend looked from their palace walls to see the flickering of fires atop the walls of Argos across the plain? Had they travelled to make offerings to Hera at her sanctuary down the mountainside on the way to Tiryns? Did they enjoy the slash of brilliant blue afforded by the Gulf of Argos that lit the distance on a clear day? Did they too savour the wine, oil, and fruit of that very same land as I was in that moment?

It that ancient landscape laced with history and myth, I felt certain that they had done all of that.

The myths are everywhere in the Argolid.

Dinnertime view from the village of Mycenae to the south from the terrace of our hotel, La Petite Planète.

The next morning we rose early with the crowing of a nearby cock and the barking of a dog, had a hearty breakfast, and drove the short kilometre up the road to the archaeological site in the hopes of beating the crowds.

It was just 8 a.m. and yet the car park was already half-full, the sun beating down, priming us for yet another day of 45 degrees Celsius.

While most of the sweating hordes of tourists went first to the museum, or a stop at the loos, we marched directly up the curving path toward the high walls of Mycenae and found ourselves with a blessedly unobstructed view of the famed ‘Lion Gate’ of the citadel.

The ‘Lion Gate’ of Mycenae

It took my breath away, though I had been before, and seen it countless times in books while doing research.

To stand in the shadow of those Cyclopean walls, before that monumental gate, to imagine Mycenaean warriors with their spears and boar’s tusk helmets staring down at you, is an experience unlike any other.

The pictures don’t do it justice.

How many kings and warriors had walked through that gate? How many chariots with bronze warriors had driven up to it? How many Trojan slaves, like Cassandra, had been forced within that stoney curtain of unimaginable size?