new release

Another New Eagles and Dragons Series Release – The Stolen Throne is out now!

Last month, we announced the release of Isle of the Blessed, the fourth book in our #1 bestselling Eagles and Dragons historical fantasy series. You can check that out by CLICKING HERE.

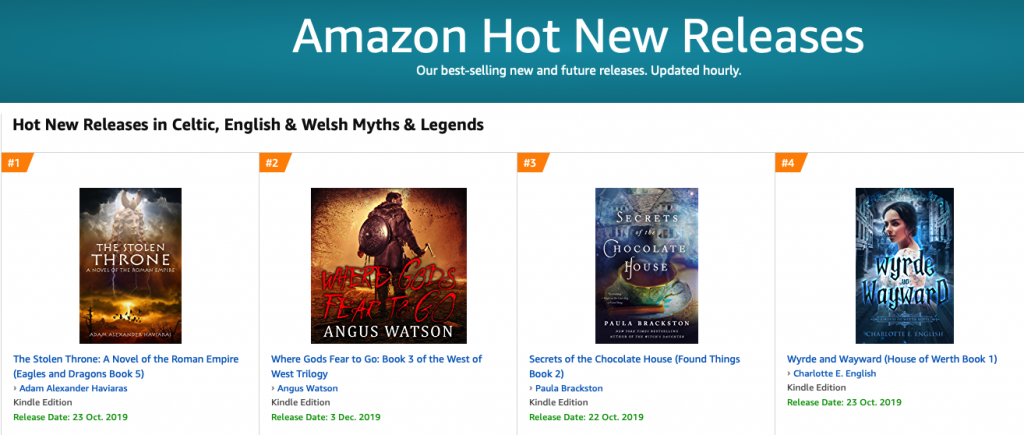

This month, we’re thrilled to announce the release of Book V of the Eagles and Dragons series: The Stolen Throne.

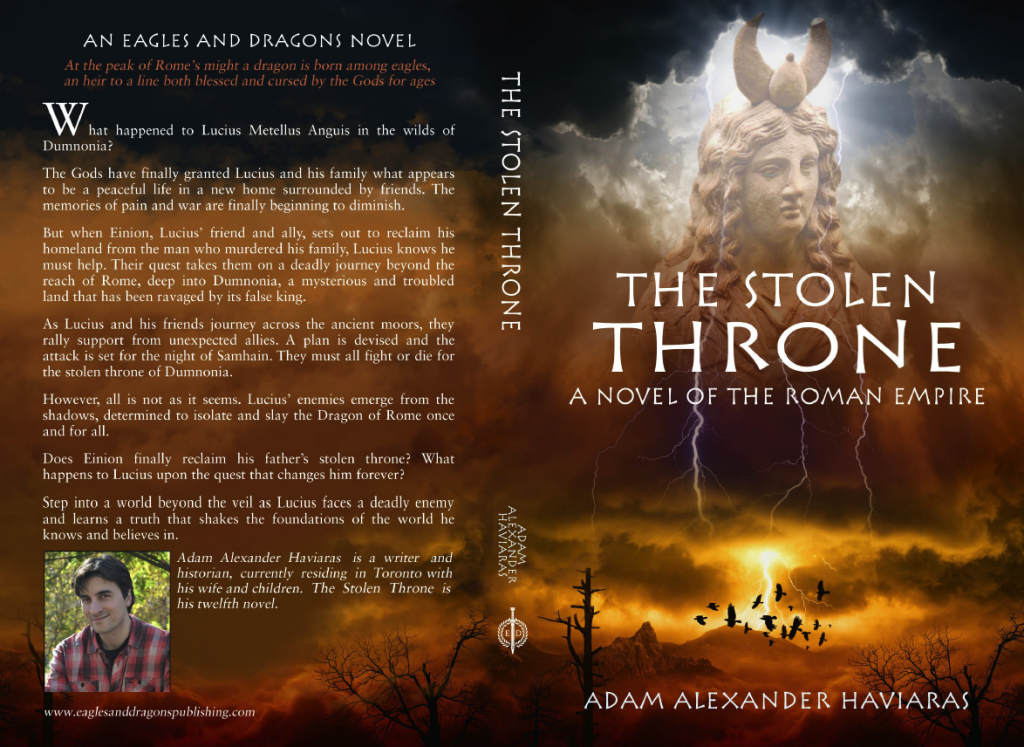

Here is the cover and synopsis of this exciting new addition to the Eagles and Dragons series:

At the peak of Rome’s might, a dragon is born among eagles, an heir to a line both blessed and cursed by the Gods for ages.

What happened to Lucius Metellus Anguis in the wilds of Dumnonia?

The Gods have finally granted Lucius and his family what appears to be a peaceful life in a new home surrounded by friends. The memories of pain and war are finally beginning to diminish.

But when Einion, Lucius’ friend and ally, sets out to reclaim his homeland from the man who murdered his family, Lucius knows he must help. Their quest takes them on a deadly journey beyond the reach of Rome, deep into Dumnonia, a mysterious and troubled land that has been ravaged by its false king.

As Lucius and his friends journey across the ancient moors, they rally support from unexpected allies. A plan is devised and the attack is set for the night of Samhain. They must all fight or die for the stolen throne of Dumnonia.

However, all is not as it seems. Lucius’ enemies emerge from the shadows, determined to isolate and slay the Dragon of Rome once and for all.

Does Einion finally reclaim his father’s stolen throne? What happens to Lucius upon the quest that changes him forever?

Step into a world beyond the veil as Lucius faces a deadly enemy and learns a truth that shakes the foundations of the world he knows and believes in.

This story will take you to a place beyond the reach of Rome’s Empire, a place full of mystery and emotion where all is not as it seems, a place from which few heroes return.

You haven’t read anything like this before!

You can learn more about The Stolen Throne (Eagles and Dragons – Book V) and find all the links to get your copy right here:

https://eaglesanddragonspublishing.com/books/the-stolen-throne-eagles-and-dragons-book-v/

The Stolen Throne is available in e-book format at all major on-line retailers, and currently in paperback from Amazon.

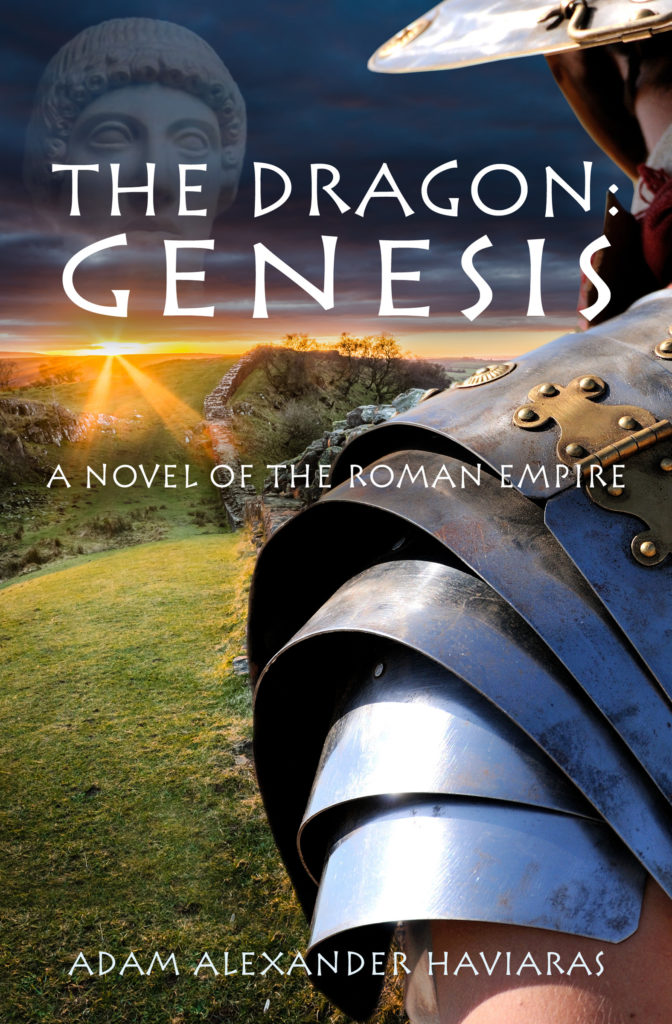

If you haven’t read any books in the Eagles and Dragons series, you can start the series for FREE with the full-length novel, The Dragon: Genesis, which you can download by CLICKING HERE.

Here’s to a new adventure in the Roman Empire!

Happy Reading!

The World of Isle of the Blessed – Part III – Ynis Wytrin: The Place Beyond the Mists

What is the Isle of the Blessed?

There are many traditions when it comes to paradise, or a place where there is no suffering or pain. To the ancient Greeks, the Fortunate Isles, or Isles of the Blessed were a place where heroes went, a green paradise where the sun always shone. To the Romans, that was Elysium, or the Elysian Fields, the place where heroes blessed by the Gods went to spend eternity in peace.

In the latest Eagles and Dragons series novel, Isle of the Blessed, we find ourselves in a world beyond the water and mist of the Somerset levels of southern Britannia.

In Part III of The World of Isle of the Blessed, we’re looking at the history, myth and legend of the place known in Celtic myth as Ynis Wytrin, but which we know today as Glastonbury, or the legendary Isle of Avalon.

Glastonbury has always been a special place for me, not because I lived in the countryside outside the town for a few years, or because of its strong Arthurian associations, an area of study and story that I have always gravitated to.

One of the things I love about Glastonbury is the, more often than not, peaceful coming together of various beliefs through the ages.

To most, the mere mention of this town’s name will likely conjure images of wild, scantily clad or naked youths and aged hippies. You’ll think of thousands of people covered in mud as they wend their way, higher than the Hindu Kush, among the tent rows to see their favourite artists rock the Pyramid Stage at Britains’ largest music festival.

It’s a great party, but that’s not the real Glastonbury.

Removed from the fantastic orgy of the music festival, this small, ancient town in southwest Britain is a place of mystery, lore and legend. It is a place that was sacred to the Celts, pagan and Christian alike, Saxons, and Normans. For many it is the heart of Arthurian tradition, and for some it is the resting place of the Holy Grail.

Today, Glastonbury is a place where those seeking spiritual enlightenment are drawn. The New Age movement is going strong here, yet another layer of belief to cloak the place.

When I lived there, I never tired of walking around Glastonbury and exploring the many sites that make it truly unique. I’d like to share some of those sites with you, sites that are featured in Isle of the Blessed, the latest Eagles and Dragons novel.

From where I lived on the other side of the peat moors, I awoke every morning to see Glastonbury’s most prominent feature shrouded in mist – the Tor.

Tor is a word of Celtic origin referring to ‘belly’ in Welsh or a ‘bulging hill’ in Gaelic. Glastonbury Tor thrusts up from the Somerset levels like a beacon for miles around. Every angle is interesting. On the top is the tower of what was the church of St. Michael, a remnant of the 14th century. Before that, there was a monastery that dated to about the 9th century A.D.

However, habitation of this place goes much farther back in time with some evidence for people in the area around 3000 B.C. It was not always a religious centre. In the Dark Ages, the Tor served a more militaristic purpose and there are remains from this period too.

In Arthurian lore, the Isle of Avalon is a sort of mist-shrouded world that is surrounded by water and can only be reached by boat or secret path. In fact, during the Dark Ages and into later centuries, until the drainage dykes were built, the Somerset levels were prone to flooding. This flooding made Glastonbury Tor and the smaller hills around it true islands. With the early morning mist that covers the levels, this watery land would have been a relatively safe refuge for the Druids, and early Christians, Dark Age warlords and medieval monks.

In Celtic myth, Glastonbury Tor, one of the traditional gates of Annwn, the Celtic otherworld, is said to be the home of Gwyn ap Nudd, the Faery King and Lord of Annwn.

Gwyn ap Nudd is the Guardian of the Gates of Annwn, an underworld god. It is at Samhain that the gates of Annwn open. This was also the place where the soul of a Celt awaited rebirth.

If you are on the Tor at Samhain, you may hear the sound of hounds and hunting horns as the lord of Annwn emerges for the Wild Hunt of legend.

In Arthurian romance, there is a tradition of the wicked Melwas imprisoning Guinevere on the Tor. Arthur rides to the rescue, attacks Melwas and saves Guinevere. This particular story mirrors an episode in Culhwch and Olwen, one part of the Welsh Mabinogion, in which Gwythyr ap Greidawl attempts to save Creiddylad, daughter of Lludd, whom he is supposed to marry, from Gwyn ap Nudd himself.

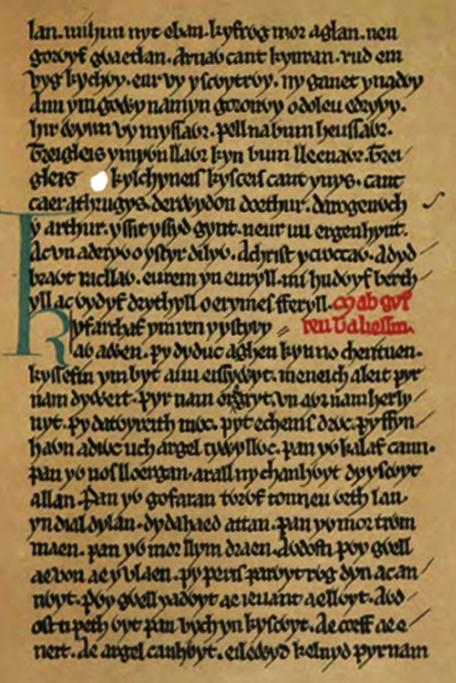

Another even more fascinating Arthurian connection can be found in a pre-Christian version of the ‘Quest of the Holy Grail’, called the ‘Spoils of Annwn’ which was found in the ‘Book of Taliesin’. In this tale, Arthur and his companions enter Annwn to bring back a magical cauldron of plenty. In this, some say that ‘Corbenic Castle’ (the ‘Grail Castle’) is actually Glastonbury Tor. It isn’t just Herakles and Odysseus who journeyed to the Underworld!

Glastonbury Tor is not only associated with Celtic religion, myth and legend. It is also said by some to be a place of power or a sort of vortex in the land that lies along some of the key ley lines, including what is called the St. Michael ley line. The majority of sites associated with St. Michael, the slayer of Satan, along the ley line were indeed places of power and belief of the old pagan religions.

Myth and legend persist through story and place, and the Tor is a prime example of how successive traditions do not overcome each other, but rather combine to make up the various aspects of that place.

If you ever get to Glastonbury, the Tor is a definite must. Walk to the top and sit awhile. Look out over the landscape and watch the crows and magpies dive in the wind around the steep slopes. Close your eyes and listen. While you’re there, you can decide whether you are sitting on a natural formation, a ceremonial labyrinth, a hillfort, a sleeping dragon, the Gates of Annwn, or the mound where Arthur sleeps until he is needed once more. The Tor is all of these things.

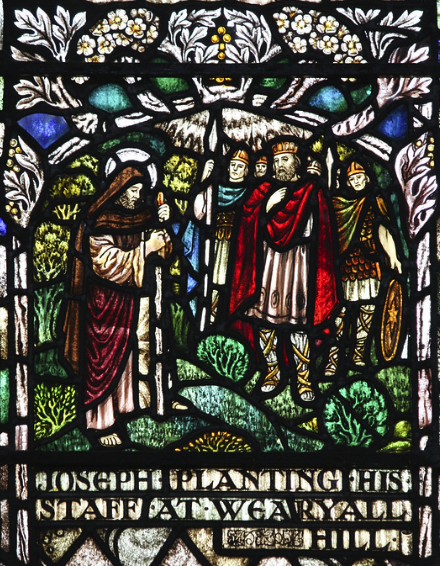

Another prominent feature of Glastonbury’s landscape is known as Wearyall Hill, located on the road as you enter from the neighbouring town of Street.

Wearyall Hill is home to one of Glastonbury’s most ancient treasures – the Holy Thorn.

Across the street from the Morrison’s store, you can climb up Wearyall’s gentle slope to see a hawthorn tree known as the Glastonbury Thorn, or the ‘Holy Thorn’. One popular legend associated with Wearyall Hill and the Holy Thorn is that in the years after Christ’s death, his uncle Joseph of Arimathea came with twelve followers by boat to Glastonbury. When they set foot on the hill, tired from their journey, Joseph plunged his staff into the ground and it took root.

There is archaeological evidence for a dock or wharf on the slopes of Wearyall Hill that dates from the period. Did Joseph of Arimathea actually arrive in Britain with the Holy Grail?

Stained glass detail from St John’s church in Glastonbury showing Joseph planting his staff in Wearyall Hill.

Well, that depends on what you believe. And Glastonbury is just that, an amalgam of beliefs living, for the most part, in harmony, just as the Celts and early Christians did here over two thousand years ago.

Cuttings of the Thorn grow in three places in Glastonbury. What is interesting is that this variety of hawthorn is not native to Britain, but is rather a Syrian variety. Curiously, it flowers at Christmas and Easter, both sacred times of year for Pagans and Christians. Every holiday season, the Royal family is sent a clipping of this very special tree that hails from the earliest days of Christianity in Britain.

The current Thorn is not the original, but rather a descendant of the original which was burned down by Cromwell’s Puritans in the seventeenth century as a ‘relic of superstition’. How much destruction has been wrought on the ancient sites of Britain during the wars waged by Henry VIII and later Oliver Cromwell? It’s horrifying to think about.

As with all other things in Glastonbury, Wearyall Hill and the Holy Thorn do not belong solely to the Christian past.

The hawthorn tree was one of the most sacred trees to the Celts and is the sixth tree on the Druid tree calendar and alphabet. It is also known as the ‘May Tree’ because of when it blossoms most. May was sacred to the ancient Celts as the time of the festival of Beltane, a time for Spring ritual and worship of the Goddess.

In the Middle Ages, the practice of picking hawthorn boughs evolved to include dancing with them around a May Pole.

In Arthurian tradition, Wearyall Hill is associated with the castle of the ‘King Fisherman’ whom the Grail knights meet. To reach the castle, those on the quest were said to have to cross the ‘perilous bridge’ over the river of Death. To pass through the castle was to go from this world to the next.

Interesting to think that the gates to the otherworld of Annwn were believed to be just on the next hill, Glastonbury Tor.

Whatever legend or myth you believe, or don’t believe, about Wearyall Hill is up to you. The stories are many and convoluted, but such is the fate of great and sacred places of the past.

I always looked forward to my walks up the gentle slope of Wearyall Hill with the Holy Thorn drawing me up like a beacon, a friend even. Locals, Christian and Pagan believers, hold it close to their hearts.

Once at the top of the hill, I would circle the Thorn, reach out to touch its limbs, and read some of the wishes or prayers on ribbons tied to it – ‘Don’t let me lose my family,’ or ‘Thank you for making my mummy better.’ The wishes wrenched your heart, and the thanks made you smile.

When I would sit on the nearby bench at the top of the hill, I never felt alone. I would look out at the Tor and the surrounding landscape and feel tremendous gratitude. I would always leave with a sense of hope for the future, and a tie to the past.

On my recent visit, long after the vandals struck, there are more wishes than ever upon the Holy Thorn.

When I returned to Glastonbury recently to film a documentary and do some research for Isle of the Blessed, I found the tree much changed from before.

In 2010, vandals took a chainsaw to the Holy Thorn in the middle of the night. In the morning, residents found their beloved tree of hope hacked to bits. A sapling was planted again in the Spring of 2013, but again, that was knocked down in the night.

I’m still in shock over this, lost in my remembrances of Glastonbury’s Thorn in full bloom on a sunlit hilltop.

But the Thorn has survived the centuries and there has been talk that new shoots have been coming up. The Royal Botanical Gardens is on the case, and so are the citizens of Glastonbury.

The Thorn and Wearyall Hill itself are not purely Christian or Pagan. They are symbols of unity, and of a common past. We should indeed cherish sites that are so revered, whether we believe in them or not.

In a way, the Thorn’s sacrifice is bringing people together. Glastonbury is still a town where Pagan and Christian live side by side.

And it is this unity that I explore in Isle of the Blessed.

I have every hope that the Thorn will blossom once again on the crest of Wearyall Hill, and that one day I’ll make the climb to say hello to a very old friend.

This next site we are going to look at is one that, like the rest of Glastonbury, is suffused with layers of history, legend, and belief.

The Chalice Well and surrounding gardens, located in a valley between Chalice Hill and the Tor, is one of those places that you don’t quite know what to make of at first. When you enter under the vine-covered pergola you are met by colour, soft light, and the gentle trickle of water playing about your senses.

You see young, wildly coloured blossoms exploding from the soil at the foot of Yew trees that have seen centuries of summers in Ynis Wytrin.

The same goes for the people visiting this place.

You will see young children frolicking like fairies at the edge of the water, adults of all ages contemplating beauty…life…death.

And you will find aged men and women, whose years are beyond the care of counting, strolling silently about the gardens. They’ll admire a particularly beautiful blossom or sit on one of the many benches hidden in private corners, perhaps remembering others they have come here with long ago. Or maybe they are just looking up at the Tor and harkening back to the tales of Arthur they loved when they too were children.

The thing about this place is its overwhelming sense of peace and harmony, from which all can benefit.

But what exactly is the Chalice Well?

Scientifically-speaking, Chalice Well is actually an iron-rich spring, the source of which is unknown. Some believe it comes from deep in the Mendip Hills to the north. The Chalice Well is where it comes out of the ground.

Springs were sacred to the ancient Celts. To those who inhabited this area from the pre-historic era on, the Well may have been a healing place beside the Tor. The waters that run red were sacred to the Goddess and were her water of life.

The spring has never failed, even in drought.

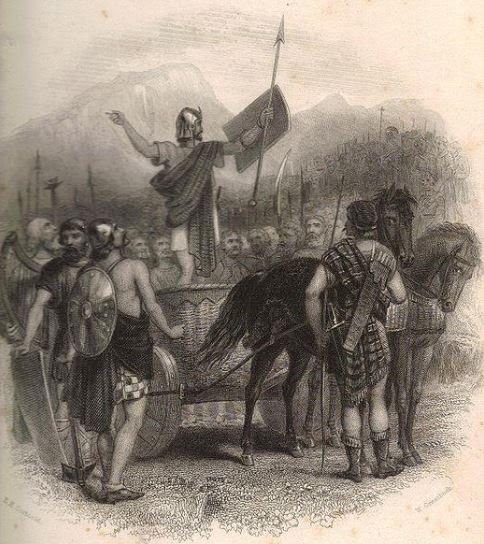

‘The Druids; or the conversion of the Britons to Christianity’. Engraving by S.F. Ravenet, 1752, after F. Hayman.

It is also believed that Glastonbury was the site of a Druid ‘college’ of instruction and that the avenue of sacred Yew trees, some still remaining in the Chalice Well gardens, were part of a processional way to the Tor, passing beside the Well.

Later legend, and the reason for the name given to the Well, relates how Joseph of Arimathea brought the Holy Grail to Glastonbury in A.D. 37. It is said that he buried the Grail near the Well and that the water runs through it, hence the redness of the water.

The Goddess’s blood was replaced by that of Christ, but the sanctity of the place remained (and remains) intact.

Of course, there is an Arthurian connection. Where you find the Grail, there too will you find Arthur and his knights.

In the 15th century, Sir Thomas Malory mentions the spring in his Morte d’Arthur when Lancelot and others are said to have retired as hermits in a valley near Glastonbury. Some believe it was this site that he referred to.

The sacred water of the Chalice Well feels like the beating heart of the gardens that surround it, and visitors, like a protective shield.

There are four places where the water surfaces in the Gardens.

The first is one of the most striking features – the well cover in the form of the Vescica Piscis.

The Vescica Piscis is an ancient symbol that represents the intersection of the material and immaterial (Natural and Supernatural) worlds. Fitting for one of the traditional gateways to Annwn.

The Chalice Well cover is made of English oak and wrought iron, and was designed after WWI by the architect and clairvoyant, Frederick Bligh Bond, who carried out the first excavations on Glastonbury Abbey.

The difference with this Vescica Piscis is that the circles are intersected by a sword, or bleeding lance, a Christian addition to this ancient symbol of power.

From the Well, the red water flows to the Lion’s Head where people can go to drink, or sit in quiet reflection while the water splashes onto a stone below.

Farther down the garden you come to a striking rich-red waterfall where the spring cascades into a pool where people can soak themselves in the healing water. This pool is another place of meditation known as Arthur’s Courtyard.

After that, the water flows past two ancient Yew trees, and a shoot of the Holy Thorn (yes, it survives!) into a pool shaped like the Vescica Piscis near where you enter the Gardens. The spring then flows away underground, beneath the Abbey and the pavement of Magdalene Street.

The red water’s healing sojourn above ground is fleeting, but for thousands of years it has brought people comfort, and peace.

Whenever I would visit Chalice Well and the gardens, my head pounding from a migraine, or the weight of a world of worries pressing me down, I would always leave feeling rejuvenated, calm, and optimistic.

Whether visitors are pagan, Wiccan, atheist, or Christian, or they adhere to some other system of belief, the Chalice Well is a place where people still believe in miracles, as they have done for thousands of years.

On the next part of our journey through Ynis Wytrin, or in insula Avalonia, we’re going to meet two very special giants.

They are tall, and broad, and green, and together they have stood the test of time. Their names are Gog and Magog.

The names of Gog and Magog will be well-known to Old Testament historians as evil powers to be overcome in the Book of Ezekiel (38-39), and in the New Testament Book of Revelation (20).

Gog and Magog also figure largely in the British foundation myths, mainly in the Historia Regum Britanniae of Geoffrey of Monmouth.

According to Geoffrey, when Brute, a descendant of the Trojan Aeneas, came to Britain in around 1130 B.C. he and his people fought a West Country giant(s) named Goemagot.

There are many other tales and places around England and Ireland associated with the giants, Gog and Magog.

In Glastonbury it is different.

The giants of which I speak are two ancient and magnificent oak trees that are tucked away in this misty isle.

They are not war, or pain, or suffering. Gog and Magog represent the last of the great oaks of Avalon. They demand nothing of the wanderer, and yet they are revered.

The association with the giants only goes so far as the names of the trees, and their size.

The short walk to the oaks from the middle of Glastonbury town is one of the most beautiful walks in the area.

Cross Chilkwell Street, near the Abbey Barn, and head up Wellhouse Lane between the slopes of the Tor and Chalice Hill. Follow the foot path into the field where you will come to the ancient trail of Paradise Lane. At the bottom of Paradise Lane, you will find Gog and Magog waiting for you.

These trees are ancient, no doubt. When they come into view, you are drawn to them as if to a comforting grandparent. You’ll find the odd ribbon tied to a branch, or a sheaf of wheat laid in offering among the sturdy limbs.

These two trees are friends to many in Glastonbury and beyond.

Gog and Magog are all that remain of an avenue of oaks that led to the Tor, and which was thought to be used as a processional way by the Druids in ages past.

Sadly, the avenue was cut down for farmland in 1906, and these two giants are all that remain.

Oak trees like Gog and Magog were sacred to worshippers of the Great Mother, and later the Druids. Before Rome and mass farming came to Britain, the whole of the south of Britain was covered in forests from Hampshire to Devon.

Oak groves were sacred, the sites of the Goddess’ perpetually burning fires and the rites of the Druids who used oak leaves in their rituals.

The sanctity of the oak was not relegated to Celtic Europe either, but also goes back to ancient Greece. At the sanctuary of Zeus at Dodona, priests would glean the will of Zeus from the rustling of the leaves in the sacred oak groves.

At Glastonbury, Gog and Magog would likely have seen many a ritual or procession.

If they could only speak in a way we could understand, I’m sure they would have some fantastic tales to tell.

Taking the walk from town, past the Tor, and down Paradise Lane to see Gog and Magog was always one of my favourite walks. Because there are no roads nearby, the sound of cars is absent, and all you can hear is the chirruping of birds and the whisper of the wind as it blows across the Somerset levels.

When I returned there to do research for Isle of the Blessed, my feet found their way there once more, whisking through the dry field grass, or squelching through the mud, until I caught that first glimpse of the two giants.

“It’s good to see you again, after so long…” I thought, feeling a great comfort and sense of gratitude.

From my days in insula Avalonia, I can still recall refreshing walks along the crest of Wearyall Hill, along the dragon’s back of the Tor, and down Paradise Lane to Gog and Magog.

However, there is another place of peace, a sanctuary in the middle of town, nestled between Wearyall Hill, Chalice Hill, and the Tor. It is Glastonbury Abbey.

The Abbey grounds, like other sanctuaries in town, are a place to get away to. You have to pay to get in, but once you walk through the arch, past another descendent of the Holy Thorn, and onto the green lawns surrounding these magnificent ruins, you are set to experience a whole new aspect of Glastonbury.

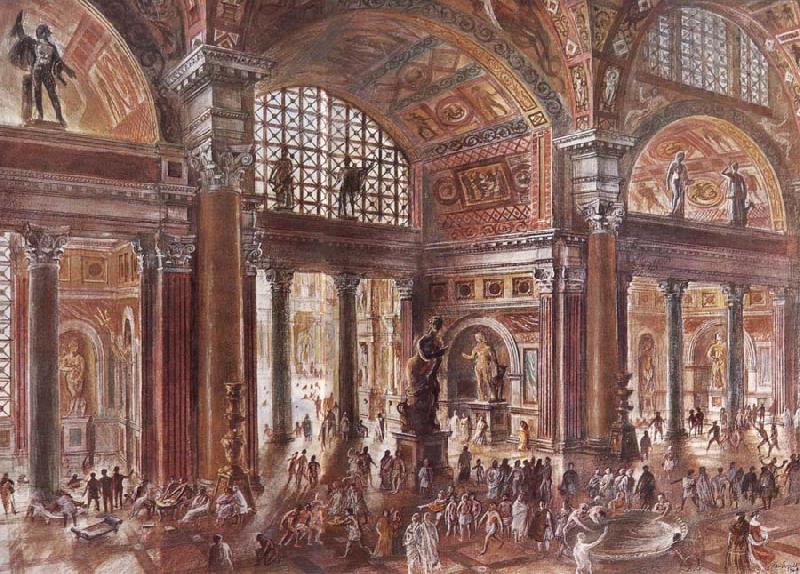

The ruins of what was once one of the largest abbeys in England rise up from the soft ground, sentry-still, surrounded by mist. ‘Majestic’ is a word I would use to describe the ruins, and ‘sad’. When you see the model of what the place looked like at its height of power and prominence, you understand.

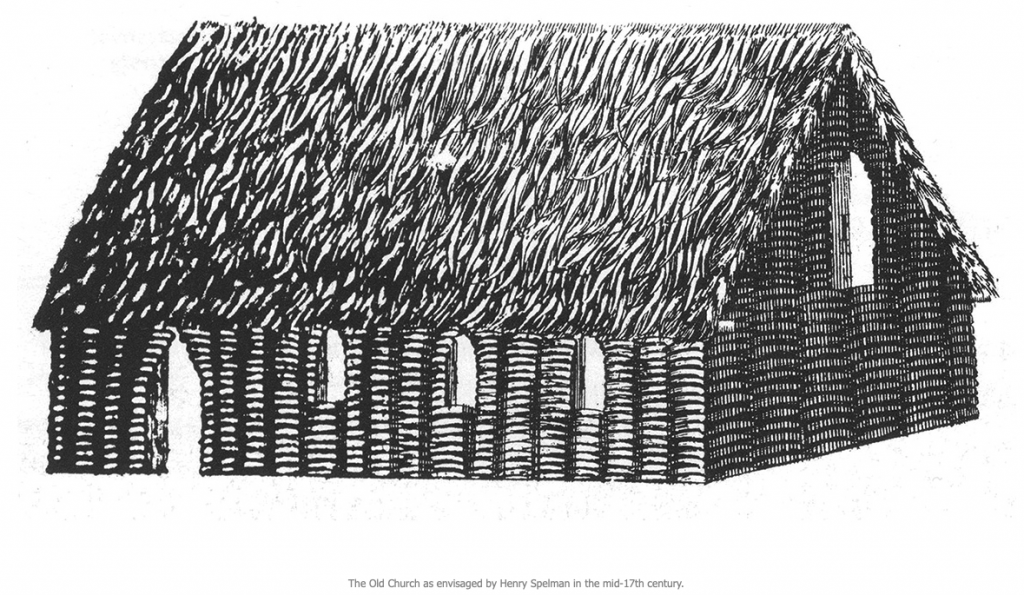

Glastonbury abbey was not always such a soaring monument of Christianity. The lovely ruins that can be seen today are a medieval creation, the remains of which date from the twelfth to sixteenth centuries. But the place itself is said to be the site of the first Christian church and oldest religious foundation in the British Isles.

Model in the abbey museum of what Glastonbury Abbey used to look like before the Dissolution of the Monasteries.

According to tradition, Joseph of Arimathea and his followers built a wattle church on the site on land he was given by the local king, Arviragus (possible ruler of South Cadbury Castle at the time) around the middle of the first century A.D.

Circa A.D. 160, two Christians named Faganus and Deruvianus are supposed to have added a stone structure on the site of what is the Lady Chapel. It is here that there is an ancient well dedicated to St. Joseph.

In the early days of Christianity in Britain, this first chapel and the well were the predecessors of the magnificent ruins of the abbey we see today. The Lady Chapel was the site of the first Marian cult in Britain, and in the words of Geoffrey Ashe “there is no rival tradition whatsoever. When all of the fantastic mists have dispersed, ‘Our Lady St. Mary of Glastonbury’ remains a time-hallowed title.”

In one of the Welsh Triads, Glastonbury is given the distinction of having a ‘perpetual choir’.

It was a place that Christians gravitated to. Indeed, several Celtic saints are said to have come here, including St. Bridget, St. David, St. Columba, and even St. Patrick whom some stories name as the first abbot of Glastonbury.

Walking the grounds of Glastonbury Abbey is a contemplative activity, like so many other spots in insula Avalonia.

It is supremely peaceful and there are all manner of flora in the gardens to add to the calm. Great trees shiver overhead when a breeze blows into town from across the Somerset levels.

You can stroll the scant remains of the cloisters and up the nave with the abbey’s stone titans looming over you. In a couple spots, you can lift a wooden cover to reveal some of the colourful tiles of the medieval abbey floor.

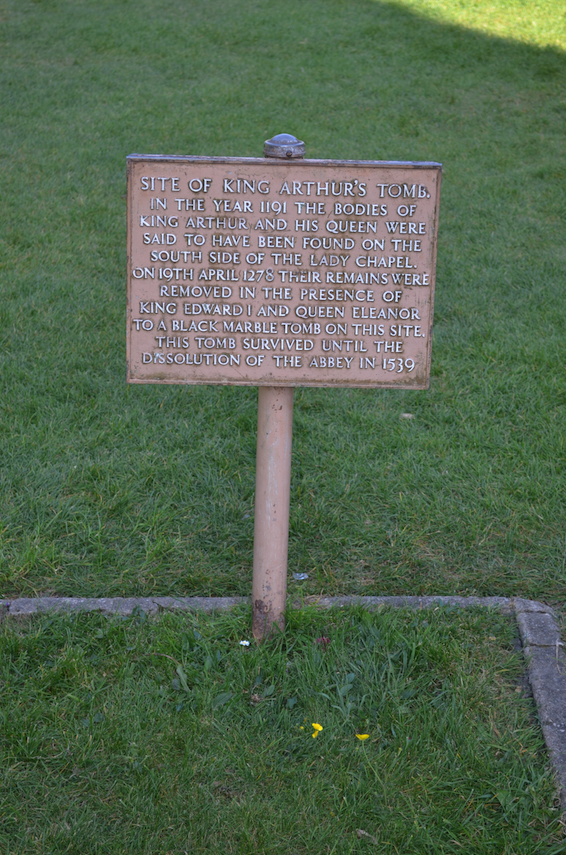

Then, toward the transept, you come to an unassuming outline in the grass with a plaque marking it.

This is where you meet with one of Glastonbury Abbey’s most mysterious connections.

In 1184 a fire ravaged the abbey and the monks needed to rebuild. Around the time of the fire, a Welsh bard is supposed to have revealed to King Henry II that King Arthur himself was buried within the abbey grounds.

The king passed this information on to the Abbot of Glastonbury who later ordered excavations to be carried out. In 1191, it is said that the monks found the bones of a man and a woman in a hollowed out tree trunk who were none other than Arthur, and his queen, Guinevere.

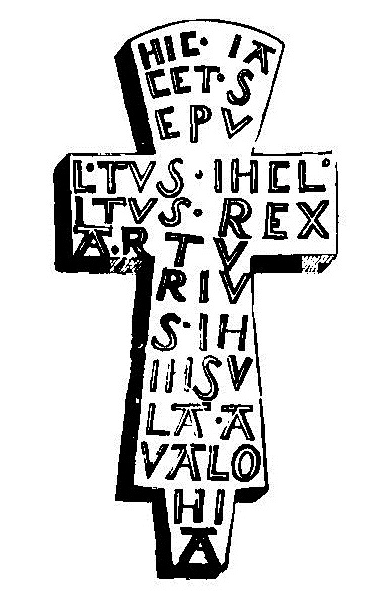

With the remains was a lead cross with the words ‘Hic Jiacet Sepultus Inclytus Rex Arturius in Insula Avallonia’ which translates as ‘Here lies buried the renowned King Arthur in the Isle of Avalon’.

The Elizabethan antiquarian, William Camden, did a sketch of the Arthur cross in the early 17th century.

A lot of doubt has been cast on the monks’ discovery with many believing that it was a hoax created by the monks to boost tourism through pilgrimage. The remains were treated as relics and later moved within the abbey during the reign of Edward I in the early 13th century.

It is important to note that the archaeologist who excavated the abbey in the 1960s, Dr. Ralegh Radford, indicated that the monks’ story might not have been that far-fetched, and that there was indeed a person of great import from the correct period buried in the graveyard just south of the Lady Chapel.

As with all things in Glastonbury, belief is always a part of the great equation.

There are other buildings associated with the abbey too, including the Abbot’s Kitchen where the Benedictine brothers would have prepared meals, and the Abbey Barn which is now home to the Somerset Rural Life Museum.

The site is lovely and inspiring. Tradition on the abbey grounds goes back ages to the very roots of Christianity in Britain and beyond, and this Christian presence comes as a surprise to the Romans who find themselves in Ynis Wytrin in Isle of the Blessed.

As I would sit on a bench, listening to the birds and the breeze, gazing upon the ruins, I would imagine St. Joseph arriving with his followers and picking out the spot for that first chapel. Perhaps they had something in common with the druids and priestesses of the goddess who might have already been there? Perhaps a common yearning for peace and truth?

It is sad that Henry VIII robbed us of the physical beauty of Glastonbury Abbey in the great Dissolution. The last abbot was dragged to the top of the Tor and beheaded by the King’s henchman, Cromwell.

For this place to function peacefully and unmolested from its earliest time, through Saxon incursions and Norman invasions, speaks to its agreed importance over the ages.

The majesty of this place may lie in ruins now, but its spirit and mystery certainly remain intact.

I hope you’ve enjoyed this post on Glastonbury and The World of Isle of the Blessed as much as I enjoyed researching, revisiting, and writing about it in the novel. It was especially inspiring to write a story set in a place people of various beliefs lived together, and then to send my Roman protagonist into their midst.

What would a Roman think of a place where pagans and Christians, including Druids, lived together in peace and harmony?

Well…to learn that, you will have to read the book.

Join us next week for Part IV of The World of Isle of the Blessed when we will be taking a look at the main historical players in the imperial court in Britannia.

Thank you for reading.

The World of Isle of the Blessed – Part II – Roman Lindinis: The Small Town with Big Ambitions

Welcome back to The World of Isle of the Blessed, the blog series in which we take a look at the research, history and archaeology that went into the latest novel in the Eagles and Dragons historical fantasy series.

In Part I, we looked at the hillfort of South Cadbury Castle which is one of the major settings of the book. If you missed that post, you can read it HERE.

In Part II, we’re going to be taking a look at another place that plays an important role in Isle of the Blessed: Roman Lindinis.

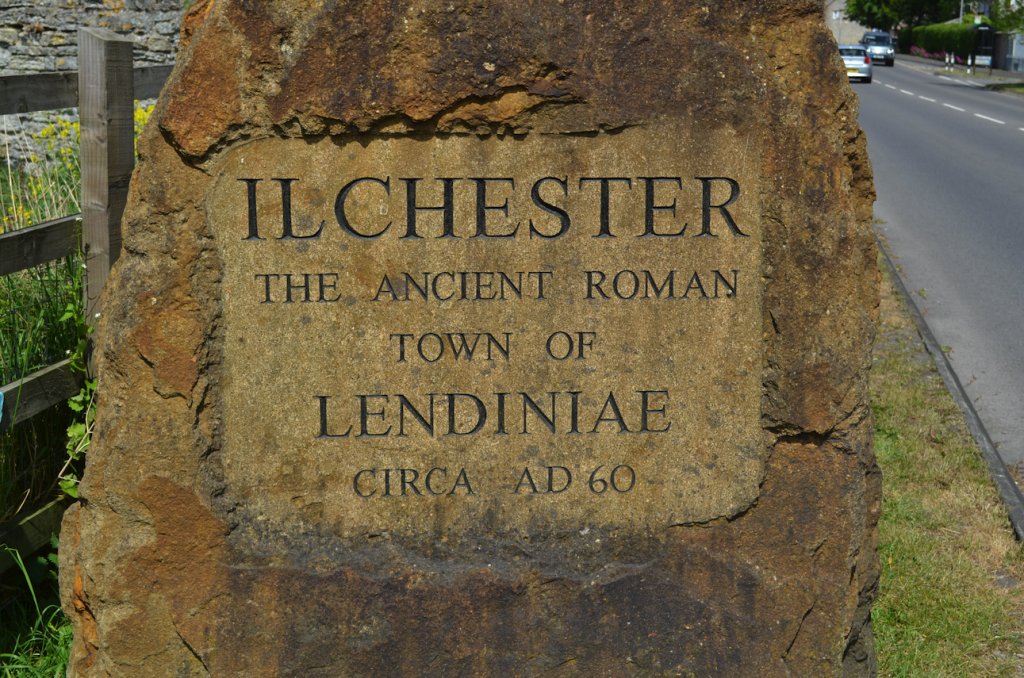

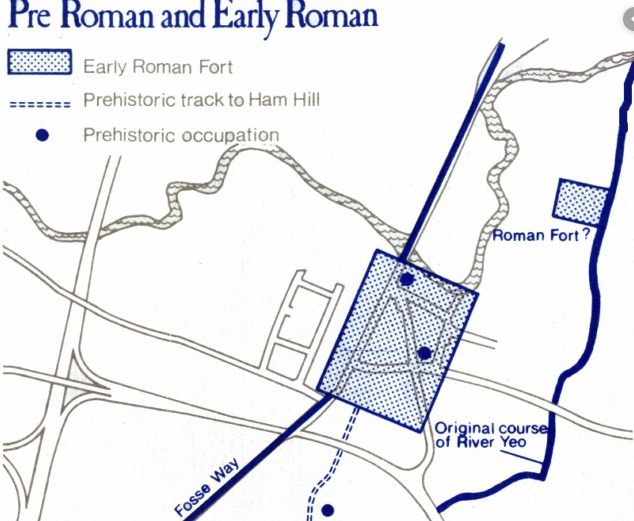

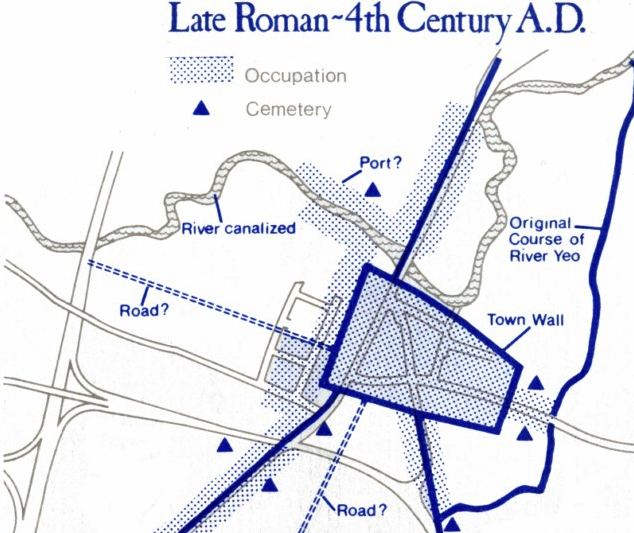

The settlement of Lindinis (also known as ‘Lendiniae’), as it is known in the seventh century Ravenna Cosmography (a list of place names from India to Ireland) is actually modern Ilchester, in Somerset, England.

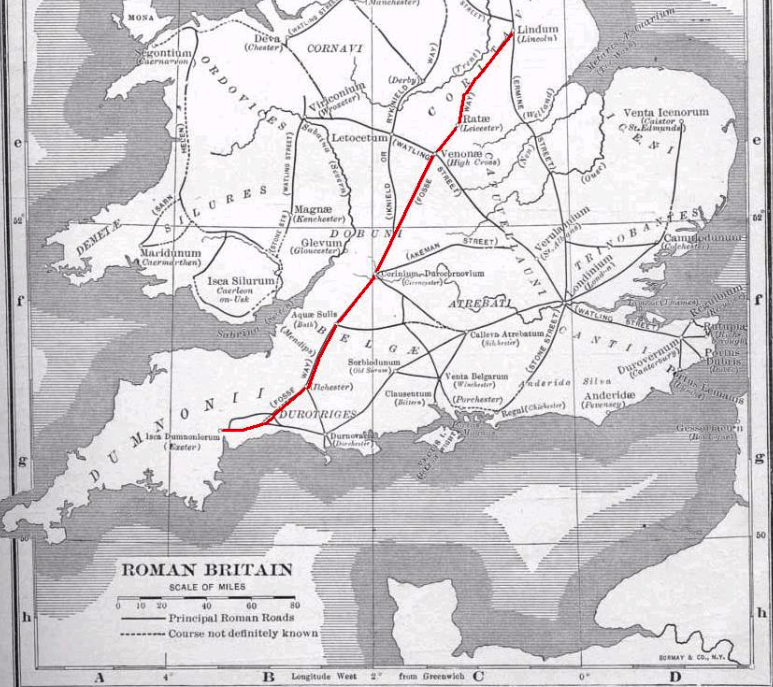

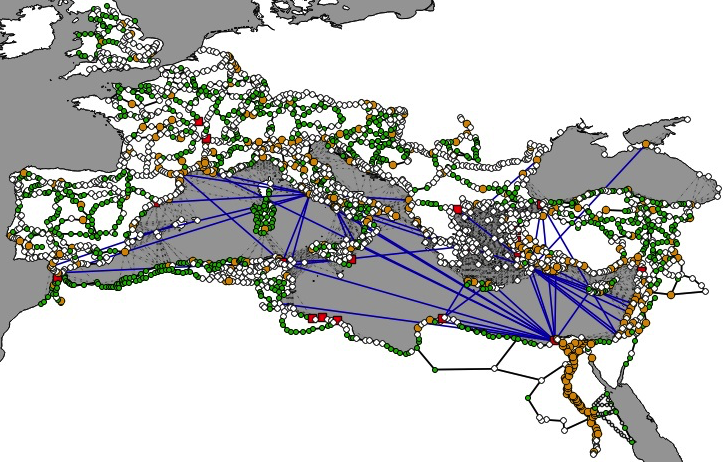

Lindinis, as it was known during the Roman period, was located just a few miles from South Cadbury Castle, and Glastonbury, Somerset. This fifty acre settlement lies where the Dorchester road interests with the Fosse Way, one of the major roads of Roman Britain.

During the Roman period, Somerset was an agriculturally rich area of the Empire, with many villa estates, such as that of Pitney (which also features in the story). These estates’ primary business was in crops such as spelt wheat, oats, barley and rye. The also raised livestock, mainly cattle, but also sheep, horses, goats, and pigs.

These Roman villa owners were wealthy, and Lindinis was one of the main markets where they brought their crops and livestock.

Lindinis was not always a Roman settlement, however.

It was originally a Celtic oppidum, a native center that consisted of a large enclosure with homes, food stores and livestock. One imagines Celtic Somerset as a place of peace and vitality.

But, in A.D. 43 the Romans arrived with the advent of the Claudian invasion of Britain. Forty-five thousand troops marched over the land, including four legions, and the native Britons fought, and lost. Vespasian, the future emperor, stormed the southern hillforts of Britain, including South Cadbury Castle, ushering in an age of Roman domination.

Eventually, at Lindinis, two successive forts were built on the site to the south of the river: one from Nero’s reign, and another during the Flavian period. There is also evidence for a third fort to the northeast of the river crossing where a double ditch enclosure has been discovered.

The Roman invasion of Britain was a violent time, and that violence carried on through the Boudiccan revolt of A.D. 59. But when the blood stopped flowing, an age of Pax Romana settled on the southwest of Britannia, and Lindinis was at the heart of it.

Lindinis, however, was not the main settlement of Roman Somerset. To maintain peace and order, and keep the economy running, the Romans instituted various civitates, centres of local government in which tribal groups of the region participated.

The council of a civitas was known as an ordo, and the members of the ordo were decurions, overseen by an executive, elected curia of two men. The ordo of a civitas usually included Romans, tribal aristocrats or local chieftains, and it was their job to administer local justice, put on public shows, see to religious taxation, the census, and represent the civitas in Londinium. Supreme authority, however, belonged to the Provincial Governor who was aided by a procurator, the ‘tax man’.

There were three major civitates during the Roman period in southwestern Britannia: Durnovaria (modern Dorchester) the civitas of the Durotriges tribe, Isca Dumnoniorum (modern Exeter) the civitas of the Dumnonii, and to the north Corinium Dobunnorum (modern Cirencester) the tribal centre of the Dobunni.

Despite its large market and location at a crossroads along the artery of the Fosse Way over the river Yoe – in the southwest, the Fosse Way ran from Isca Dumnoniorum (modern Exeter) to Aquae Sulis (modern Bath) – Lindinis was not one of the major civitates of the region, though it did rival nearby Durnovaria.

In addition to a thriving market where wine, oil, clothing, ornaments, jewellery, tools, pottery and glass were sold, Lindinis also had gravel and stone streets, and stone walls (later). People also came to Lindinis to pay their taxes.

Where the road diverges in Ilchester – the left to Exeter, the right to Dorchester. See the bridge over the river directly ahead.

There was also a small garrison.

Lindinis may have seen itself as the civitas Durotrigum Lendiniensium, but it could not be an official civitas as one of the requirements for civitas status was a basilica or forum. Lindinis did not have either of those.

Roman Lindinis had a large role to play in the economy of Roman Somerset, but perhaps not as large as its ordo would have liked. It also found itself in difficult situations during its time, for during the civil war (A.D. 193) between Septimius Severus, Pescennius Niger, and Clodius Albinus, Lindinis was forced to declare for Clodius Albinus who was in Britannia when he made his claim. At this time, new defences were built around Lindinis, as if in anticipation of the trouble to come.

In the book, Isle of the Blessed, Lucius Metellus Anguis, the main protagonist in the Eagles and Dragons series, has several run-ins with the ordo members of Lindinis’ ruling council who see him as a person of influence at the imperial court, a man who could help their small town to become much more.

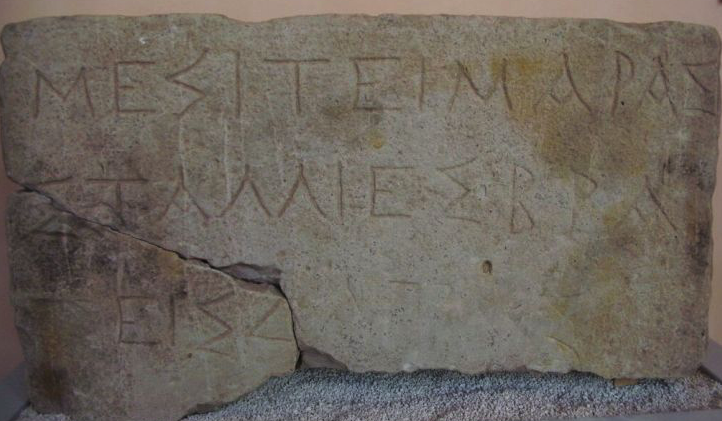

Historically, despite its lack of a proper forum or basilica, it seems that Lindinis did succeed in attaining a measure of civitas status, for along Hadrian’s Wall, two inscriptions have been found bearing the name of a detachment from the ‘Civitas Durotragum Lendiniensis’, or the ‘Lindinis tribe of the Durotriges’.

This, despite the presence of the other three, official civitas settlements Durnovaria, Isca, and Corinium.

Who knows? Perhaps the persuasiveness of the ordo members of Lindinis, the settlement’s important location, and the size of its market helped to sway the Roman authorities to grant civitas status.

In Isle of the Blessed, we see how far the local politicians are willing to go.

I hope you’ve enjoyed part two of The World of Isle of the Blessed.

Next week, in Part III, we will look at the history, myth and legend surrounding what is known in Isle of the Blessed as Ynis Wytrin, that is, Glastonbury, England.

Thank you for reading.

Isle of the Blessed is now available in e-book and paperback from all major on-line retailers. If you haven’t read any books in the Eagles and Dragons series yet, you can start with the #1 bestselling A Dragon among the Eagles for just 0.99! Or get the first prequel novel, The Dragon: Genesis, for FREE by clicking HERE.

The World of The Dragon: Genesis – Part VI – The Antonine Plague: Pestilence and Pandemic in Ancient Rome

Welcome back to The World of The Dragon: Genesis. In our last post delving into he research for our latest historical fantasy novel, The Dragon: Genesis, we looked at the joint rule of Marcus Aurelius and Lucius Verus. If you missed it, you can read it HERE.

In Part VI of this blog series, we’re going to be looking at one of the most brutal enemies Rome has ever had to face, an enemy that slipped past the frontiers and penetrated the heart of Rome itself.

We’re not talking about barbarian tribes north of the Danube frontier, or waves of Parthian cataphracts from the East. No, the most deadly enemy Rome had to contend with during the reign of Marcus Aurelius and Lucius Verus was the plague.

And it almost completely destroyed the Roman Empire.

The ‘Antonine Plague’, as it is now known, began in A.D. 165 and lasted into the early 180s. It was the largest pandemic Rome had ever had to deal with to that point in its history.

This was an enemy that did not discriminate when it came to victims.

…after the victory over the Parthians, there occurred so destructive a pestilence, that at Rome, and throughout Italy and the provinces, the greater part of the inhabitants, and almost all the troops, sunk under the disease.

(Eutropius, Roman History, Book VIII)

Before we get into the few specifics of the Antonine Plague, we should first take a look at how Romans viewed disease, and what could have started a pandemic of these proportions.

In the ancient world, Roman medical practices were a strange mixture of practical Greek methods and Roman religious beliefs.

Disease and plague were to be feared, and the gods who were associated with them were to be propitiated.

In the Roman world, it was believed that sulphurous fumes that came out of the earth could be responsible for epidemics and plagues. As a result, the Romans made offerings to the Mefitis, a goddess of sulphurous fumes and of plagues.

A cult of Mefitis began in the volcanic regions of central and southern Italy, and her main shrine was located in Samnite territory on the slopes of the volcano of Ampsanctus.

In Rome, there was a temple of Mefitis on the Esquiline hill, and at Cremona, in the North of Italy, there was a temple dedicated to the goddess of plagues just outside the city walls.

In addition to offerings to the Goddess of Plagues and Fumes, the Romans also held games in the hopes that these – also an aspect of religion – would help them to avoid disease and keep this deadly enemy from their doors.

The Ludi Saeculares, or Secular Games (also known as the Tarentine Games) were held once every century with the intention that they would help Rome avoid pestilence.

The fist Secular Games were held by the consul Publius Valerius Poplicola in 509 B.C. at the altar of Dis and Proserpina located on the Campus Martius at a spot known as ‘Tarentum’, hence the other name of ‘Tarentine Games’.

In addition to sport, the games also included three days and three nights of stage plays.

One has to wonder how it was decided when the Ludi Saeculares were to take place, and details are sketchy about this. But, we do know of two other instances in which the games were held.

In 17 B.C. the Emperor Augustus held the games which culminated in a ceremony at the temple of Apollo, on the Palatine hill, a temple Augustus built. Among other things, Apollo was a god of healing. (Those who have read Children of Apollo, will be familiar with this temple.)

The Ludi Saeculares were also held in A.D. 204 by none other than Septimius Severus who came out the winner in the civil war that followed the death of Commodus, Marcus Aurelius’ son and heir.

Severus’ games came in the wake of the Antonine Plague, so it is likely that after the devastation, it was believed the gods needed to be propitiated once more.

What might have been the causes of the spread of disease in ancient Rome?

There are several possibilities.

First of all, sewage and bad hygiene were a prime suspect.

When we think of ancient Rome, we tend to think of baths, running water, pristine white marble etcetera, but this is not entirely accurate. Despite the presence of running water and sewer systems, the truth was that many Romans did not have access to these things, especially in poorer neighbourhoods like the Suburra. In ancient Rome, most sewers were privately owned by the rich, and so, in the poor, tightly-packed neighbourhoods where tenement blocks rose up from the streets, often the only place to dump faeces, garbage and other waste was directly onto the street. With the preponderance of flies and dogs around all this filth, bacteria was everywhere.

Another reason why disease might have spread were the public baths.

This seems contrary to what one might expect, but despite the Roman propensity for bathing and cleanliness, the hot water used in the baths of Rome and elsewhere was not cleaned chemically like today (using chlorine). As a result, bacteria would have thrived in the public baths.

Diet could also play a role in the spread of disease, especially as many Romans were malnourished. The diet of the average Roman consisted mainly of grains, distributed by the state. They had some vegetables and fruit, but meat was actually uncommon, and when they did have meat, there were no food standards to ensure freshness and quality. And so, food was often contaminated with parasites, as was the drinking water of most people.

Disease spread easily in densely populated areas, and as one of the most populous cities in the world at the time, Rome was especially vulnerable. This was certainly true in poorer neighbourhoods where many people shared small spaces, making the transmittal of disease easier.

The Antonine Plague was said to be transmitted through touch.

Lastly, another reason for the possible spread of plague and disease was deforestation around Rome and especially along the banks of the River Tiber. The clearing of trees led to the creation of rising water and an increase in the size of the marshes near Rome where mosquitoes and other carriers of diseases, such as malaria, flourished.

Coastal lagoon along shores of Lake Fogliano in the Pontine Plain – breeding ground for mosquitoes and diseases like malaria (Wikimedia Commons)

Part of the The Dragon: Genesis takes place during the Antonine Plague which began in A.D. 165.

This particular disease, however, did not originate in the city of Rome.

From A.D. 161-166, Emperor Lucius Verus was waging war against the Parthians in the East. While they were in Seleucia, a sickness began to spread among the troops of his legions, a sickness that they brought back with them to Rome and other parts of the Empire.

It was his [Lucius Verus] fate to seem to bring a pestilence with him to whatever provinces he traversed on his return, and finally even to Rome. It is believed that this pestilence originated in Babylonia, where a pestilential vapour arose in a temple of Apollo from a golden casket which a soldier had accidentally cut open, and that it spread thence over Parthia and the whole world. Lucius Verus, however, is not to blame for this so much as Cassius, who stormed Seleucia in violation of an agreement, after it had received our soldiers as friends. This act, indeed, many excuse, and among them Quadratus, the historian of the Parthian war, who blames the Seleucians as the first to break the agreement.

(Historia Augusta, The Life of Lucius Verus, 8)

What little we know of the disease comes from the observations of the physician, Galen, who was called upon by Marcus Aurelius and Lucius Verus at the time, and who recorded some of his observations in scattered texts, including his Methodus Medendi.

From Galen’s descriptions, it is thought today that the Antonine Plague was an outbreak of small pox. The symptoms included severe fever, diarrhea, pharyngitis, and on the ninth day of the illness, the appearance of skin eruptions (boils or pustules).

And there was such a pestilence, besides, that the dead were removed in carts and wagons. About this time, also, the two emperors ratified certain very stringent laws on burial and tombs, in which they even forbade any one to build a tomb at his country-place, a law still in force. Thousands were carried off by the pestilence, including many nobles, for the most prominent of whom [the emperor] erected statues. Such, too, was his kindliness of heart that he had funeral ceremonies performed for the lower classes even at the public expense…

(Historia Augusta, Life of Marcus Aurelius, Part I, 13)

The Antonine Plague brought devastation to Rome and the Empire at large. Cassius Dio wrote that it caused up to 2000 deaths a day in Rome itself. It has been estimated that there were approximately 5 million deaths from this pandemic, and that about one third of the Empire’s population was wiped out.

One theory for the widespread destruction wrought by the Antonine Plague is that this was the very first time small pox appeared in the Empire, and so, without any sort of prior immunity, the people were as lambs to the slaughter.

It also massacred the army in which it had started, spreading to Gaul and along the entire Rhine and Danube frontier. Rome’s defences were down, and the tribes to the north chose this moment to attack.

It is hard to imagine the terror spreading across the Empire during this terrible time in which Rome was beset by the Marcomanni and their allies in the north and the plague at its heart.

Eventually, the barbarians were defeated – and that alone is a wonder! – but the plague, even though it eventually stopped, left the Roman Empire scarred. Entire towns were wiped out and outposts were lost because the troops were too sick to fight.

It has also been hypothesized that the Roman embassies that Marcus Aurelius had sent to China’s Han emperor were perhaps responsible for the outbreak of plague that was recorded there.

There can be little doubt that the Antonine Plague was perhaps the most deadly crisis Rome had ever been faced with. The plague did not discriminate, striking at rich and poor, weak and strong alike. It seems likely that it was also responsible for the death of Emperor Lucius Verus, who died two years into the northern wars, and maybe even Rome’s great philosopher emperor, Marcus Aurelius, who passed in A.D. 180 just before the end of the pandemic.

He died in the following manner: When he began to grow ill, he summoned his son and besought him first of all not to think lightly of what remained of the war, lest he seem a traitor to the state. And when his son replied that his first desire was good health, he allowed him to do as he wished, only asking him to wait a few days and not leave at once. Then, being eager to die, he refrained from eating or drinking, and so aggravated the disease. On the sixth day he summoned his friends, and with derision for all human affairs and scorn for death, said to them: “Why do you weep for me, instead of thinking about the pestilence and about death which is the common lot of us all?” And when they were about to retire he groaned and said: “If you now grant me leave to go, I bid you farewell and pass on before.” And when he was asked to whom he commended his son he replied: “To you, if he prove worthy, and to the immortal gods”. The army, when they learned of his sickness, lamented loudly, for they loved him singularly. On the seventh day he was weary and admitted only his son, and even him he at once sent away in fear that he would catch the disease. And when his son had gone, he covered his head as though he wished to sleep and during the night he breathed his last. It is said that he foresaw that after his death Commodus would turn out as he actually did, and expressed the wish that his son might die, lest, as he himself said, he should become another Nero, Caligula, or Domitian.

(Historia Augusta, Life of Marcus Aurelius, Part II, 28)

I hope you’ve ‘enjoyed’, or at least learned something from this post on the Antonine Plague and disease in ancient Rome.

If you have not read our latest historical fantasy novel The Dragon: Genesis, you can download a copy for FREE by Clicking Here.

Stay tuned for the seventh and final part in The World of The Dragon: Genesis blog series in which we will look briefly at the sibling rivalry that beset the reign of one of Rome’s most infamous emperors – Commodus.

Thank you for reading.

A New Release from Eagles and Dragons Publishing!

Salvete, historical fantasy lovers, and Romanophiles!

We have a very special announcement here on Writing the Past.

This week, we’re launching the newest title in the Eagles and Dragons Publishing catalogue, and we can’t wait to share it with you.

Are you ready?

It’s called…

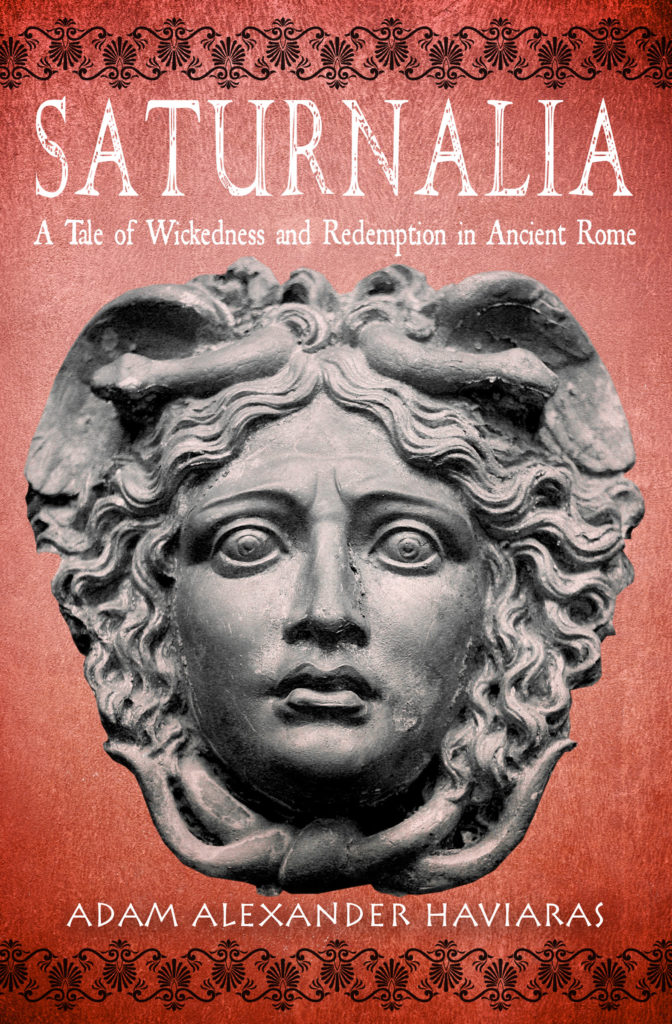

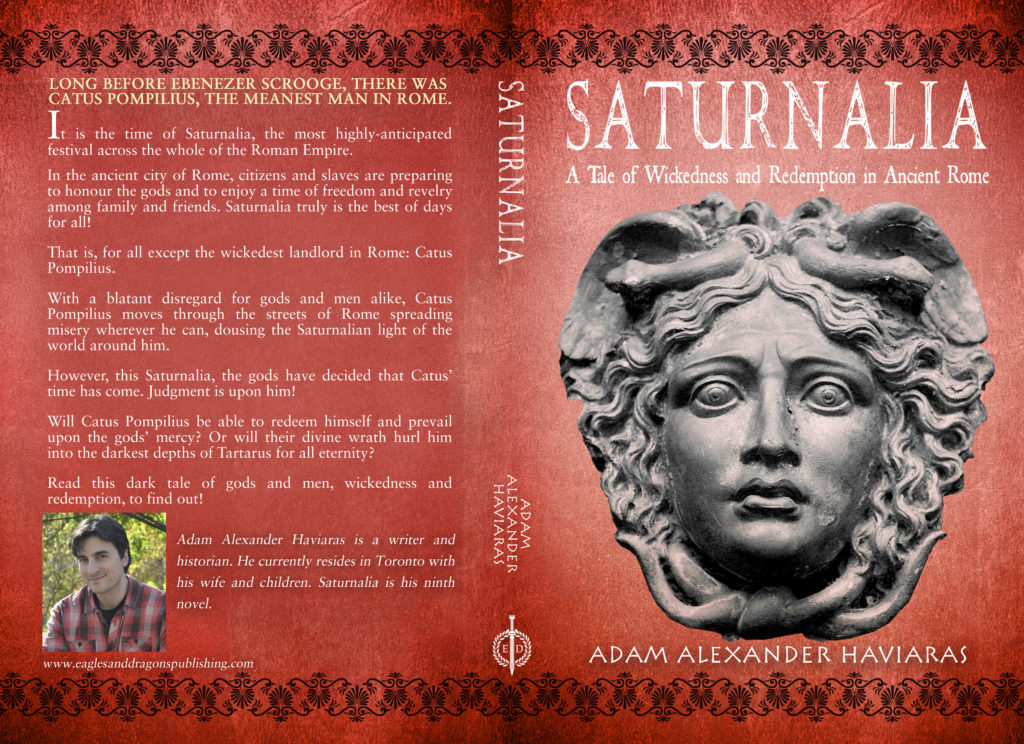

Saturnalia: A Tale of Wickedness and Redemption in Ancient Rome

We’re very excited about this novel. Here is the wonderful cover, designed by the incredibly-talented Laura Wright LaRoche at LLPix Designs…

So, what is Saturnalia all about?

Here is some background.

Every year before Christmas, I like to read an original, unabridged version of A Christmas Carol, by Charles Dickens. CLICK HERE for a free download of the e-book.

Most people are familiar with this classic tale, and for me, as a reader and author, I think it is perhaps one of the most perfectly executed and moving stories ever written.

I never tire of reading it, and every time I do read it, I take something new away with me.

Dickens’ tale of Ebenezer Scrooge is also one that has been told and retold myriad times over the years in fiction, musicals, theatre, and film. Even Matthew McConaughey and Barbie have their own versions of this story!

Which leads me to Saturnalia.

The last couple of times I read A Christmas Carol, I found myself thinking that this story, or something akin to it, would be amazing set in the world of ancient Rome, not during Christmas, but during Saturnalia, one of the most glorious festivals of ancient Rome.

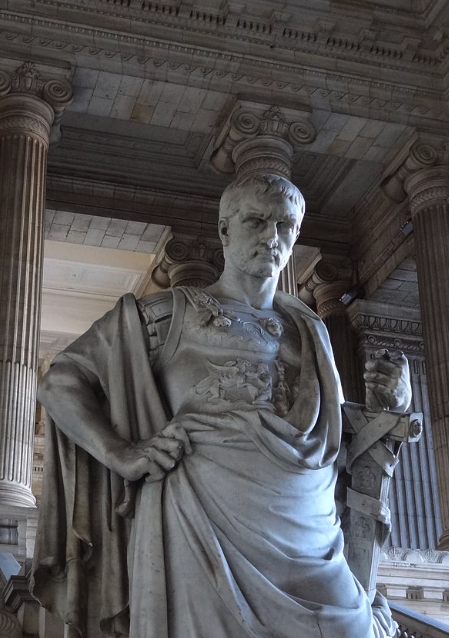

So, inspired by the Republican era bust of Cato the Elder, I set out to write my own version of the story.

With Saturnalia, however, I didn’t just want to retell the story verbatim, but rather use the framework of Dickens’ tale to guide me as a sort of story architecture. It was important to me that I make my own, unique mark on the story. It was important to me that I set it firmly in the world and traditions of ancient Rome from a historically-accurate point of view, but also from the point of view of ancient belief and religious practices.

And I’m quite thrilled with the results!

Here is the full synopsis of Saturnalia: A Tale of Wickedness and Redemption in Ancient Rome…

Long before Ebenezer Scrooge, there was Catus Pompilius, the meanest man in Rome.

It is the time of Saturnalia, the most highly-anticipated festival across the whole of the Roman Empire.

In the ancient city of Rome, citizens and slaves are preparing to honour the gods and to enjoy a time of freedom and revelry among family and friends. Saturnalia truly is the best of days for all!

That is, for all except the wickedest landlord in Rome: Catus Pompilius.

With a blatant disregard for gods and men alike, Catus Pompilius moves through the streets of Rome spreading misery wherever he can, dousing the Saturnalian light of the world around him.

However, this Saturnalia, the gods have decided that Catus’ time has come. Judgment is upon him!

Will Catus Pompilius be able to redeem himself and prevail upon the gods’ mercy? Or will their divine wrath hurl him into the darkest depths of Tartarus for all eternity?

Read this dark tale of gods and men, wickedness and redemption, to find out!

Saturnalia isn’t just a tale for the holiday season, something to read by the side of a cozy fire. This story is something that fans of ancient Rome will, I hope, enjoy anytime of year.

And for fans of the Eagles and Dragons series, the time period and city of Rome will feel very familiar to you.

The book is available for pre-order in some stores now, but the official launch is on November 1st, 2018, and there will be special notice for Eagles and Dragons Publishing subscribers.

So, dear friends, do stay tuned and watch your in-boxes!

Thank you for reading, and we do hope that you enjoy this new and exciting journey into the world of ancient Rome!

Historia II – Arthurian Romance and the Knightly Ideal

Welcome back, history-lovers!

Last week on the blog we announced the launch of Eagles and Dragons Publishing’s new non-fiction series, HISTORIA. We also introduced you to the first book in the series about Celtic archetypes in the Welsh Mabinogion. If you missed that post, you can check it out by CLICKING HERE.

This week, we’re happy to introduce you to the second volume in the HISTORIA series:

Arthurian Romance and the Knightly Ideal: A study of Medieval Romantic Literature and its Effect upon the Warrior Culture in Europe

This book explores the history and effects of one of the great literary movements in medieval Europe: Arthurian Romance.

This is not just a study of the Arthurian romances and the authors of the genre. It is a study of the true nature of chivalry and courtly love. It is also a look at a revolutionary and inspiring movement and cultural shift among the nobles of medieval Europe, one that altered perceptions of violence and the roles of men and women, influenced social change, and molded the image of the ideal knight.

In this book, the reader will learn about the origins and history of Arthurian Romance, the emergence of courtly culture, the greatest authors of Arthurian Romance, and the evolution of tournaments during the Middle Ages.

Explore the relationship between violence and the knightly ideal, and discover how medieval Arthurian Romance and its ideals may have played a role in civilizing the warrior classes of Europe and creating a new order of chivalry.

If you have an interest in medieval history and literature, Arthurian studies, or if you simply have fond memories of tales of knights and ladies, then you will enjoy this in-depth study of one of the great literary achievements of the Middle Ages.

This might come as a surprise to some of you, but my main field of study over the years has been Arthurian studies, not just the history and archaeology related to the Dark Ages and the search for an understanding of the historical ‘Arthur’, but also the romantic literature that attracted me to the Arthurian legends in the first place.

Of course, the main author that stands out is Chrétien de Troyes who really perfected and popularized the genre of Arthurian Romance.

The writings of Chrétien de Troyes not only influenced my study and perception of history, but they also influenced my own writing a great deal. Perhaps it was because I was first introduced to them at an early age, a time when I was really trying to find myself and my purpose in life, a time when I was filled to the brim with idealism.

In some ways, Arthurian Romance helped to save me from becoming too jaded with the world. It has been my sword and shield during darker times.

What is fascinating is that Arthurian Romance did indeed spark a sort of revolution during the Middle Ages, and enticed the violent knightly class to aspire to something greater than themselves.

Arthurian Romance really did create a new order of chivalry.

I’ve done a lot of research over the years, and this book summarizes much of that work in what I hope is a very accessible way.

If you are interested in getting a copy of this second book in the HISTORIA non-fiction series, you can check it out on Amazon, iTunes and Kobo by CLICKING HERE.

You can also purchase a copy directly from Eagles and Dragons Publishing on the ‘Buy Direct from Eagles and Dragons’tab of the website, or by CLICKING HERE.

Next week, we’ll introduce you to Book III in the HISTORIA series, so stay tuned for that.

Cheers, and thank you for reading!

HISTORIA – Announcing a new Non-Fiction series from Eagles and Dragons Publishing!

Greetings history-lovers!

This week on the blog, we’ve got an exciting announcement…

Eagles and Dragons Publishing has launched HISTORIA, a new line of non-fiction books that make the study of ancient and medieval history and archaeology accessible for everyone.

Books in the HISTORIA series will introduce readers to a variety of subjects in the form of short, easy-to-understand papers and books.

The first few books, which are now available, focus on my love of Arthurian and Celtic Studies and introduce readers to his academic research over the years.

More books will be added to the HISTORIA series over time, and they will cover history and archaeology from ancient Greece and Rome right through to the Middle Ages. There will be something for everyone!

HISTORIA: A Gateway to Ancient and Medieval History and Archaeology!

This week, we wanted to introduce you the very first title in the HISTORIA series. The full title is ‘Celtic Literary Archetypes in The Mabinogion: A Study of the Ancient Tale of Pwyll, Lord of Dyved’.

This book introduces the reader to some of the literary traditions of the ancient Celts through the study of the first branch of The Mabinogion: Pwyll, Lord of Dyved. This ancient text is both a record of British mythology and a teaching text for ancient princes. It also illustrates the values of Celtic, Iron Age society that carried on into the Middle Ages to shape Arthurian Romance and ideals of chivalry and kingship.

In this book, the reader will learn about the most prominent archetypes in ancient Celtic literature such as occurrences in threes, the importance of contact with the Otherworld, what it meant to be an effective ruler, and more.

Pwyll, Lord of Dyved is a tale of magic and wonder, as well as human trial and experience, and the archetypes it employs are as relevant today as they were over fifteen-hundred years ago.

If you are studying The Mabinogion, or have an interest in Celtic and Arthurian studies, the Arthurian legends and British mythology, then you will enjoy this short, engaging study of one of the great literary achievements of the ancient Celts.

Some people might be surprised that when it comes to historical periods, my interests are, first and foremost, deeply entrenched in what is commonly called the ‘Dark Ages’. To me, that is the Arthurian period, and tales in The Mabinogion are a wonderful source from that time and the traditions that arose out of it.

Why the Dark Ages? Well, to me, the period is a sort of bridge between the classical and medieval worlds. It may have been a time of darkness and despair, with the fall of the Western Roman Empire and the effects that had, but it was also a time of hope, of new beginnings. It was perhaps not so much a ‘Dark Age’ as an Heroic Age.

When I first read The Mabinogion, and especially the tale of Pwyll, I was drawn in by the magic of it. After studying it in an academic setting, my eyes were opened to the tale’s importance, and in this new book I endeavour to share some of my research on it with all of you.

If you are interested in getting a copy of this first book in the HISTORIA non-fiction series, you can check it out on Amazon, iTunes and Kobo by CLICKING HERE.

You can also purchase a copy directly from Eagles and Dragons Publishing on the ‘Buy Direct from Eagles and Dragons’ tab of the website, or by CLICKING HERE.

Next week, we’ll introduce you to Book II in the HISTORIA series, so stay tuned for that.

Cheers, thank you for reading, and thank you for joining us on this new adventure for Eagles and Dragons Publishing!

THANATOS: Death and the Carpathian Interlude

Today I’m very excited to announce that Thanatos, Part III of the Carpathian Interlude, is finally out in the world!

I know this novella has been a long-time-coming, especially for those of you who have e-mailed me to say that this series is your favourite of all my books.

It feels rather strange to finish this trilogy. It’s the end of a journey that began as a bit of fun, but then quickly turned into something a lot more serious, gruelling, and frankly…painful.

I have a confession to make to you…

The first draft of this book was finished over two years ago.

Yes, you read that correctly.

I regret that I’ve left fans of this series hanging for so long since the release of Lykoi (Part II). However, I wasn’t ready to deal with Thanatos for some time after typing ‘The End’ on it.

This is where I get very personal with you, dear readers.

You see, when I was about half way through writing this story, my father passed away very suddenly. He was alone, away from his family, on his way to work.

The event hit my family like a Dacian raiding party in the dead of night.

I was floored…paralyzed.

But I knew that if I did not finish Thanatos then, while I was in the flow, I never would. So, a few days after this sad occasion for my family, I sat down for hours one night and fought my bare-fisted, bloody way to the end of the novel.

People say that when times are tough, writing can be one of the most cathartic activities you can undertake.

And you know what?

It’s true. Despite the brutality of that writing session, and the darkness of the story itself, it did help me in a way.

When it was done, when I finally typed ‘The End’, my grief poured out and the fog I had been caught in began to lift.

For a long time, I wondered how bad the story might be, that I might have just dumped my chaotic grief onto the page. That’s another reason this took so long to get out.

But this past fall, I finally handed the manuscript to my editor, dreading the feedback I would get and the sight of red all over the paper like vicious sword wounds.

It seems however, that pain and brushes with death can indeed give life to creativity.

When she returned the manuscript of Thanatos to me, my editor told me she thought it was perhaps one of the best things I’ve written yet.

Now for a bit about the story itself…

As I mentioned, The Carpathian Interlude series was originally intended to be a bit of fun, but it quickly became serious.

Despite the fantastical elements of the stories with zombies (Immortui) and werewolves (Lykoi), a fair amount of research has gone into these novels, and Thanatos is no exception. As always, I have striven for accuracy when dealing with the historical parts of these books.

Mithras and Mithraism, which was an important religion among Roman soldiers, are a big part of these books. Thanatos really delves into ancient Zoroastrianism, of which Mithraism is a part.

The historic event that these books revolve around is the Battle of the Teutoberg Forest in A.D. 9, in which Quinctilius Varus lost three of the Emperor Augustus’ legions in the forests of Germania. It was a time of terror in the Empire.

I also did a great deal of research into Dacians, their gods, and the Dacian capital of Sarmizegethusa for Thanatos; it was a fascinating rabbit hole to fall into.

For those of you who like the follow the history and research of my novels, never fear, for later this year I’ll be posting a blog series called The World of The Carpathian Interlude. Stay tuned for that.

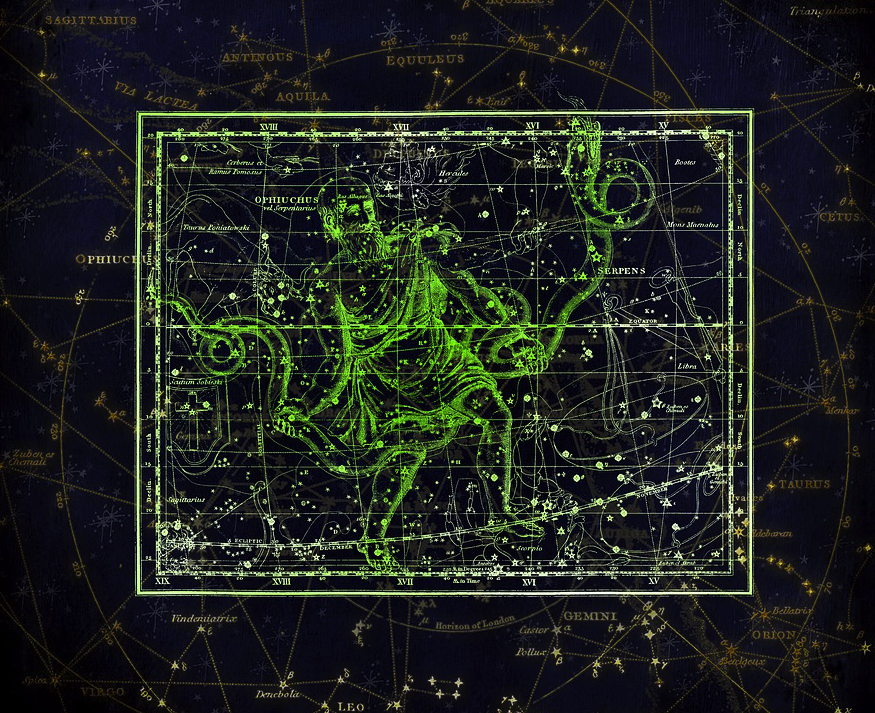

Some of you may also be wondering about the title of Thanatos.

‘Thanatos’ is the Greek word for ‘Death’. This is deliberate on my part, and directly tied to the Carpathian Lord in the stories.

However, that is where the ties to the ancient Greek image of ‘Thanatos’ ends.

In ancient Greek tradition, Thanatos was a winged god, the twin brother of Hypnos (Sleep). In Hesiod’s Theogeny, Thanatos is the son of Nyx (Night) and Erebos (Darkness).

Thanatos was the personification of Death, and to the ancient Greeks, it was his duty to usher the spirits of the dead to the appointed place, a role later more associated with Hermes. To the ancient Greeks, he was a dreaded god, but not wicked or evil.

In Part III of the Carpathian Interlude, Thanatos is a much more ancient evil, an enemy of the gods in the battle between Light and Dark.

As I said, there will be a blog series about all the research for the Carpathian Interlude trilogy coming out later this year.

In the meantime, I do hope you enjoy this new story, and that it gets you thinking, even in the darkest of places.

Thank you for reading, and may you walk in the Light…

To get a copy of Thanatos, or read the synopsis of this final part in The Carpathian Interlude, just click the link below to go to the book’s page:

http://eaglesanddragonspublishing.com/books/thanatos-carpathian-interlude-part-iii/

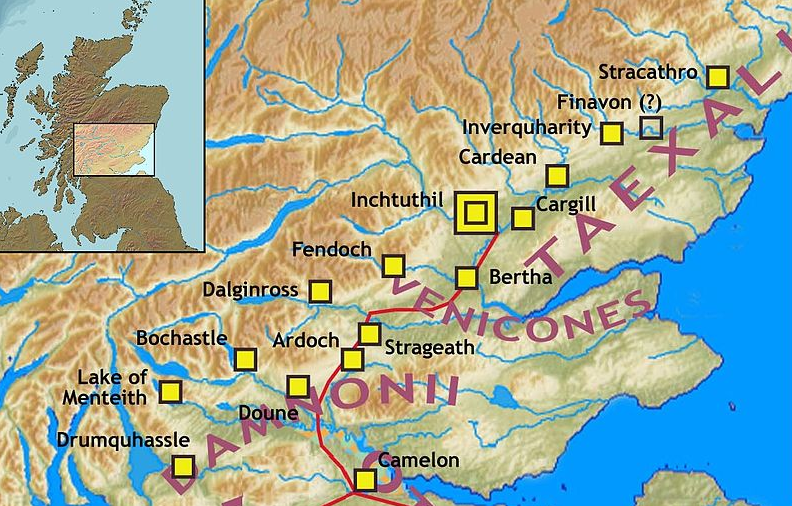

The World of Warriors of Epona – Part IV – Battle Line: The Gask Ridge Frontier

When most think of the Romans in Britannia or Caledonia, almost always the first thing that comes to mind is Hadrian’s Wall.

But there is another frontier that many people may not know of. You may have heard of some of the forts or camps that make up a part of this frontier, such as the legionary base at Inchtuthil.

Roman re-enactor watching the frontier

I’m talking about a line of forts and camps known as the ‘Gask Ridge’.

Research on this particular frontier has been less in depth than either the Antonine or Hadrianic walls. However, over the past ten years or so, the Gask Ridge has received its due attention thanks to the efforts of Birgitta Hoffmann and David Woolliscroft who have spearheaded the Roman Gask Project.

The importance of this frontier cannot be over-emphasized.

Gask Ridge Forts (Wikimedia Commons)

The Gask Ridge frontier has seen action in every one of Rome’s Caledonian campaigns and some of the research even shows that it was the first chain of forts in northern Britain, predating the other walls.

Some believe it is the first such frontier in the Empire!

It consists of a long line of forts, watchtowers, and temporary marching camps that run from the area of Stirling, on the Antonine Wall, past Doune, along the edge of Fife and up into Angus, all the way to Stracathro.

This is a very impressive line of defence built by Rome with the intent of holding the Caledonii at bay, and separating the highlands from the flatter plains leading to the North Sea.

Artist Impression of Caledonian Warriors

In writing Warriors of Epona, the trick was finding out which forts may have been in use during the campaigns of Septimius Severus in the early 3rd century A.D.

The forts of the Gask Ridge were used mostly during Agricola’s campaign in the late first century, and then by Antoninus in the mid-second century.

Roman road along Gask Ridge in Perth and Kinross

The Romans definitely knew how to pick a strategic location along the perfect line of march, so it’s likely marching camps would have been reused in later campaigns. But some of that is supposition.

One site that we know was built as part of the Severan campaign was the legionary fort at Carpow, on the banks of the Tay. With a large part of a legion stationed there, the supply chain could be maintained by sea with Roman galleys coming up the Tay. It was also at this time that some believe the first Tay Bridge was built when Severus ordered the creation of a boat or pontoon bridge to the Angus side of the river.

Aerial view of Horea Classis site (Carpow)

Carpow was a large base of operations intended to make a statement – Rome was going to stay this time! Severus was a military emperor who liked to prove his point. He was in Caledonia to finish what other Roman emperors had started, just as he did in Parthia.

The Gask Ridge plays a key role in Warriors of Epona, especially the forts that may have seen re-use during the third century, among them the forts at Camelon, Ardoch, Fendoch, and Bertha, the latter being where Lucius Metellus Anguis establishes his forward base.

Ardoch Roman camp remains

Of course, one of the exciting things about writing historical fiction, after the research, is filling in the gaps and exploring possibilities.

Because research on the Gask Ridge is relatively new, we can certainly look forward to learning more from Hoffmann, Woolliscroft, and everyone else on the Roman Gask Project team who are leading the charge to further our knowledge of this ancient frontier.

One thing that I have discovered over the years is that even though the history and research are very important, at the end of the day, in fiction, the story must come first.

With Warriors of Epona, history and story have come together nicely, and that has been pure magic!

Cheers, and stay tuned for the fifth and final part of The World of Warriors of Epona.

Aerial view of Fendoch and the Sma’ Glen from the south with the fort on the low plateau in the right foreground.

If you are interested in reading more about the Roman Gask Frontier, or about the Romans in Scotland, do have a look at the following resources:

The Roman Gask Project: http://www.theromangaskproject.org/

Rome’s First Frontier: The Flavian Occupation of Northern Scotland. By D. J. Woolliscroft and B. Hoffman. Pp. 254. ISBN: 0 7524 3044 0. Stroud: Tempus. 2006.