Interview with Adam (Yup! C’est moi!)

Hi everyone!

This is not my blog post for the week. I just wanted to let you all know that I’ve been interviewed on my previous guest’s website.

Effrosyni has a great blog where she interviews a lot of fantastic authors. Definitely go and check it out!

And if you are curious about what is going on behind the scene in my writing life, do have a read of the interview. Effrosyni asks some great questions!

Click HERE to head on over and read the interview.

Thanks, and I’ll see you all with a fantastic post on mythology in a couple days.

The Goddess Athena and her Sacred Temple, The Parthenon – With Special Guest, Effrosyni Moschoudi

Today we have a very special guest on Writing the Past.

Effrosyni Moschoudi is a fellow author whose books have been making a big splash on the Amazon charts and on book review sites around the web.

I’ve read her book, The Necklace of the Goddess Athena, and it is a wonderful book that is full of mystery, wonder, and goodness. Click HERE to read my review of it.

For a while I’ve wanted to have Effrosyni, a native of Athens, guest post here to talk about the ancient city and the bright-eyed goddess for whom it is named.

So, over to Effrosyni for a magical post…

GODDESS ATHENA AND HER SACRED TEMPLE, THE PARTHENON

A Guest post by Effrosyni Moschoudi

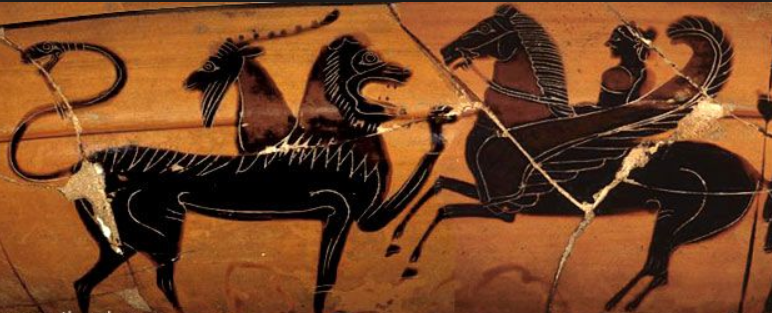

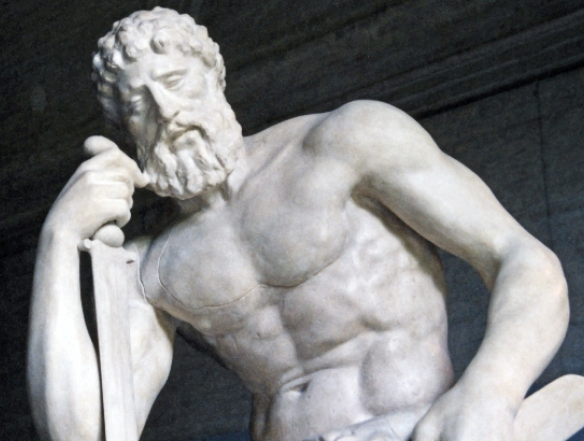

Goddess Athena was greatly revered by the ancient Greeks. One of her many epithets, Pallada (or Pallas), was owed to the peculiarity of her birth. According to legend, she sprang forth from the forehead of her father Zeus, fully armed and shaking her spear fiercely, making a fearsome sound. The word Pallada is derived from the Greek word ‘pallein’ which means ‘to shake’.

This divine young virgin was among other things, the goddess of wisdom and justice. Her sacred symbols include the owl and the olive tree. According to legend, she challenged Poseidon on the Athens Acropolis aiming to win the patronship of the city. The two Gods agreed to each offer a gift before king Cecrops and the witnessing Athenians; the better gift would grant the deity the greatly desired patronship status.

Poseidon went first, striking the Acropolis Rock with his trident to produce the Sea of Erechtheus; a salt spring. As the myth goes, the Athenians weren’t particularly impressed with this gift, as the water wasn’t fit to drink. Poseidon then offered a second gift, a horse, to be used for war. When Athena’s turn came, she struck the ground with her spear and an olive tree sprouted from it swiftly; a magnificent gift to be used for nourishment, beauty and light in the dark. King Cecrops and the people of Athens favored the gift of the olive tree and declared Athena the patron deity of the city that inevitably took on her name.

According to myth, Poseidon was enraged by this and stormed to western Attica, where he flooded the Thriasian Plain. His rivalry with Athena, even though she is his niece, is legendary in Greek mythology. Homer’s Odyssey illustrates it heavily, telling the world of this fearsome uncle and his cunning niece who fight over the fate of Odysseus. The cunning Greek king and his loyal crew roamed the sea for years, going through infamous trials and tribulations as they made their way back home to Ithaca after the Trojan War. Although Poseidon tried to lead Odysseus to his demise, furious with him for blinding his beloved son, The Cyclops Polyphemus, Athena kept going against his will assisting Odysseus out of difficult situations, until he made it safely home back to his palace and faithful wife, Penelope.

The Athenians loved their patron Goddess like no other deity. During the Golden Age of Athens (460-430 BC), under the leadership of Pericles, they built the Parthenon atop the Acropolis hill, along with other glorious edifices; all of them famous through history in their own right as well: The Propylaea, The Erechtheion and The Temple of Athena Nike.

Famous architects Iktinos and Kallikrates took over the construction and the legendary sculptor Phidias was commissioned to create the colossal chryselephantine (gold and ivory) statue of Athena for the interior of the Parthenon, which was named Athena Parthenos (Athena The Virgin). Phidias also sculpted the gigantic bronze statue Athena Promachos (Athena standing in the front line in battle). This statue was placed between The Parthenon and The Propylaea.

The word Parthenon is also derived from the word ‘parthenos’ which means ‘virgin’ as per the epithet ‘Virgin’ for Athena. Once in four years, the Panathinaia Festival took place in honor of the Goddess. Although it also involved athletic events similar to the Olympic Games, the main event was the religious procession that made its way from The Parthenon to the town of Elefsis via Iera Odos (The Sacred Way); today, Iera Odos survives as a busy motorway between Athens and the historical town of Elefsis (also spelled Eleusis in English). This historic town is also the very site of the infamous Eleusinian Mysteries of antiquity that to this day, historians know very little about.

Over the millennia, The Parthenon, one of the seven wonders of the ancient world, has suffered devastation repeatedly and on a large scale. Other than being occupied by the Turks and turned into a mosque in the 1460s, it was also bombed by the Venetians in 1687, cruelly looted by Lord Elgin in 1806 and has even suffered substantial damage by overzealous Christian priests who destroyed the depictions on the friezes that seemed indecent in their eyes.

In order to graphically illustrate the Parthenon back in its glory days as well as its demise through the millennia, I’m including below a remarkable video by the Greek Ministry of Culture. I hope you’ll also enjoy therein, a classic poem by the legendary philhellene, Lord Byron. The great romantic poet’s imagination has captured the wrath of Athena (Minerva, in Roman) further to the merciless destruction of her sacred temple. For the benefit of poetry lovers, I’m also including a link to the whole poem, written in Athens in 1811 by the great British poet.

CLICK HERE to read The Curse of Minerva by Lord Byron

Effrosyni Moschoudi was born and raised in Athens, Greece. As a child, she often sat alone in her granny’s garden scribbling rhymes about flowers, butterflies and ants. Through adolescence, she wrote dark poetry that suited her melancholic, romantic nature. She’s passionate about books and movies and simply couldn’t live without them. She lives in a quaint seaside town near Athens with her husband Andy and a naughty cat called Felix.

Her debut novel, The Necklace of Goddess Athena, is a #1 Amazon bestseller in Greek & Roman literature. This urban fantasy of Greek myths and time travel is suitable for all ages. In 2014, it made the shortlist for the “50 Best Self-Published Books Worth Reading” from Indie Author Land.

Her second novel, The Lady of the Pier – The Ebb, is an ABNA Quarter-Finalist. Set in England in the 1930’s and in Greece in the 1980’s, it follows the lives and loves of two young girls who’ve never met but are connected in a mysterious way.

Effrosyni’s books are available in kindle and print format.

CONNECT WITH EFFROSYNI

Amazon Author page

Blog

Goodreads

The Necklace of Goddess Athena in paperback and Kindle e-book.

I’d like to thank Effrosyni for taking the time to write this fascinating piece for Writing the Past.

In reading it I felt nostalgia gripping me as it has been several years since I last walked Athens’ ancient streets and gazed up at the Parthenon atop the Acropolis.

I definitely recommend The Necklace of the Goddess Athena, not only for the beautiful story, but also for the feeling of living in Athens today alongside the Gods themselves.

As ever, thank you for reading, and remember to leave your comments below!

Chariot of the Son – The First in a New Series

Today, I’m happy to announce the first book in a new series from Eagles and Dragons Publishing.

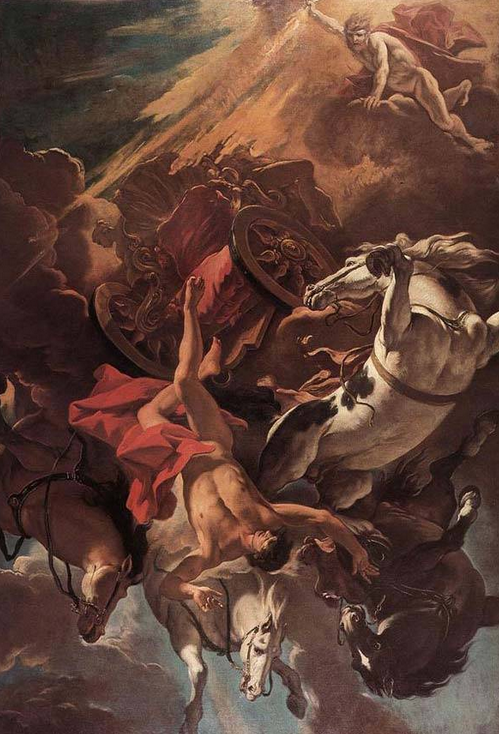

It’s called Chariot of the Son, and it is a retelling of the Phaethon myth from Greek mythology. But, before I talk about the story, I’d like to mention the series.

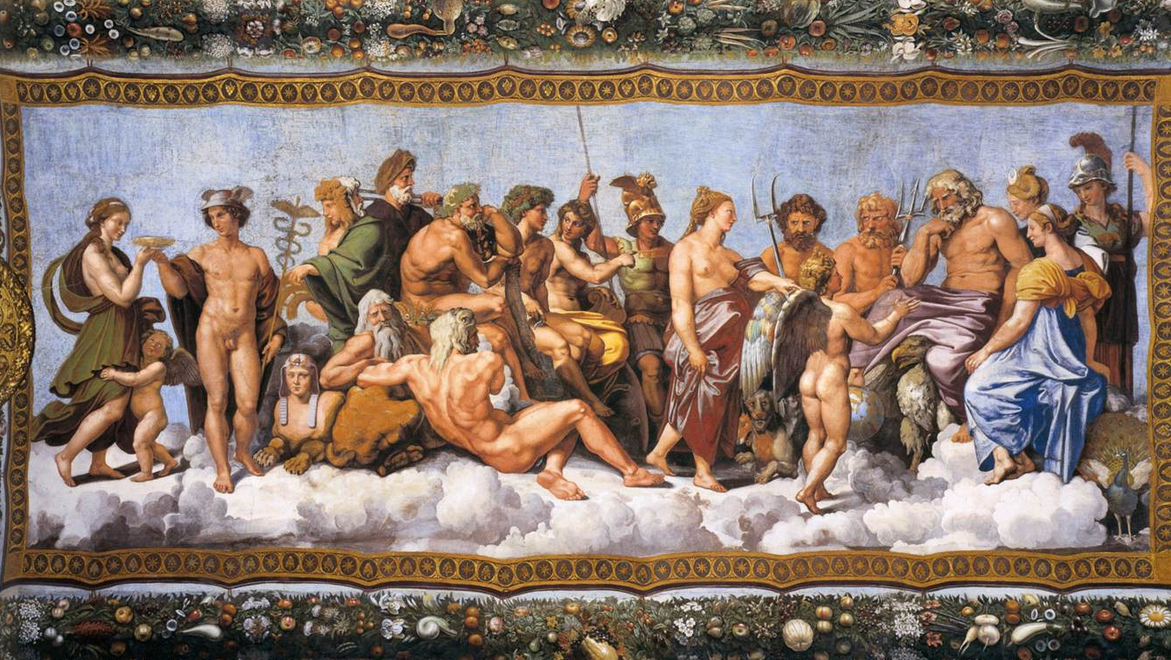

I’ve always enjoyed Greek mythology, and as I’ve grown older and begun to write my own stories, I’ve realized that it would be wonderful to retell many of these fabulous myths in a way that would allow us to get to know these gods, goddesses, and heroes on a more personal level.

There are several myths I would like to delve into, and Chariot of the Son is the first in what I am calling the Mythologia series.

The goal with the Mythologia series is to re-create a mythical world in which the reader can suspend all disbelief and experience these epic tales in a new and exciting way, right alongside the immortals and demigods whom we have read about for ages.

This series is also a lot of fun for me to write because anything goes; I don’t need to be constrained by historical timelines or detail as much as with other series. I get ideas from the seeds and scattered mentions by authors in various texts over the ages, and then let my imagination run wild.

Why the Phaethon myth?

I forget what I was researching at the time, but I came across a description of one version of the tale and remember being really saddened by it. I felt strongly that this was a story that I could tell, a story that would be extremely moving for readers of all ages.

There are a few versions of the Phaethon myth, including Hesiod’s Theogeny of the 8th or 7th century B.C., and versions by Apollodorus and Pausanias in the second century A.D. In these, Phaethon is often the son of Eos and Kephalos.

The version that touched me the most is by the Roman poet Ovid (43 BC – AD 17/18) from Book II of his work, Metamorphoses. This work is a continuous narrative of myths in fifteen books which has shaped much of our view of mythology to this day.

With Chariot of the Son, I wanted get to know the people who, unbeknownst to Phaethon, make up the family – Clymene and Helios, his parents; his sisters, the Heliades; as well as the Titan Prometheus, and more.

Also, knowing that the story has a tragic end, I wanted to get inside this young god’s heart and mind to try and experience the reasons why he wanted so much to drive the Sun’s chariot across the heavens.

I’m very excited about this book, and writing it was, quite literally, a dream-like experience.

Stepping into such an ancient world where these mythic characters experience things on a very human scale has been a wonderful experience that I hope you will enjoy.

And, now for the cover reveal for Chariot of the Son…

Many thanks to OctagonLab for the great cover which, quite suitably, blinds us with beauty and intensity.

Chariot of the Son will be released on December 7th, 2014.

However, you can read an excerpt of the book on the Eagles and Dragons Publishing website by clicking HERE.

If you like what you read, the book is available for pre-order for a special price from Amazon right now.

And remember, if you don’t have a Kindle, there are FREE Amazon Kindle reading apps that will allow you to read on your iPhone, iPad, Android phone, computer and other devices. Just click HERE!

I hope you enjoy this new book, and thank you for reading…

Chariot of the Son

Chariot of the Son is an epic retelling of the story of Phaethon from Greek Mythology.

During the age of Gods and Titans, Phaethon spends his days alone on the plains of Ethiopia, his only joy in life watching the Sun travel across the heavens.

When the sad bonds of his life are about to overwhelm him, a truth is revealed to Phaethon which sends him on a quest across the world to find his place in the order of things, and to unite the family that he has never known until now.

This is a story of love and loss, of deep yearning to find one’s place and to make a difference in a world where even the Gods can weep.

The World of Children of Apollo – Part III – The Severans

The Severans were a very interesting family and not without their tales of violence and greed and uniqueness of character. The period is not marked by something so brutal as the psychotic reign of Caligula, but there are certainly many more dimensions. It is a time of militarism, of a weakened Senate, a time of spymasters in various camps. It is a time marked by the rise of lower classes, the presence of powerful women and, over it all, a blanket of religious superstition at the highest levels. Many believe that it is this period in Rome’s history that marks the true beginning of the end of the Roman Empire.

The emperor at the time that Children of Apollo takes place is Septimius Severus (A.D. 193-211). He was the son of an Equestrian from Leptis Magna in North Africa. When Commodus was killed in A.D. 192, Severus was governor of Pannonia. When the Praetorians decided to auction the imperial seat a short time later, Severus’ legions declared him Emperor. He subsequently defeated his two opponents who had also declared themselves Emperor: Clodius Albinus and Pescennius Niger. A purge of his opponents’ followers in the Senate and Rome made Severus sole ruler of the largest empire in the world.

Septimius Severus was a martial emperor, the army was his power and he knew how to use it, how to keep the legions loyal and happy. He increased troops’ pay and in a radical move, allowed soldiers to get married. Severus was good to his troops, his Pannonian Legions and victorious Parthian veterans. He promoted equestrians to ranks previously reserved for aristocrats and lower ranks to equestrian status. There was a lot of mobility within the rank system at the time due to Severus ‘democratization’ of the army. Remember, this was an emperor who favoured his troops, especially those who distinguished themselves. The Emperor is open and friendly with Lucius Metellus Anguis in Children of Apollo, but there are prices to be paid. No favour is free.

One of the most interesting characters of the period is Severus’ Empress, Julia Domna. She appears as one of the strongest women in Rome’s history, an equal partner in power with her husband who heeded her advice but also respected her. Julia Domna was the first of the so-called ‘Syrian women’, she and her sisters hailing from Antioch where their father had been the respected high priest of Baal at Emesa (Homs in modern Syria).

Julia Domna was also highly intelligent, known as a philosopher, and had a group of leading scholars and rhetoricians about her. They came from around the Empire to be a part of her circle, to win commissions from her. No doubt, her strength also bought her a great many enemies, including the Praetorian Prefect and kinsman to Severus, Gaius Fulvius Plautianus. The conflict between the Empress and the Prefect of the Guard is something that will cause Lucius Metellus Anguis a good deal of trouble in Children of Apollo and sequel, Killing the Hydra. To boot, Plautianus’ daughter, Plautilla, was married to the Empress’ son, Caracalla. One can imagine what family gatherings must have been like!

Apart from the power, their keen ability to wield it, and their nurturing of the army’s loyalty, a very interesting and important aspect of Septimius Severus and Julia Domna is the great faith they both placed in astrology and horoscopes. They consulted with their astrologer and the stars on all decisions. Astrology affected everything, including Severus’ choice of her as his wife – he was greatly impressed by her horoscope.

By all accounts Caracalla and Geta, Severus’ heirs, were both at odds much of the time. The two brothers seem to have tolerated each other’s presence and competed fiercely, even in the hippodrome where at one point they raced each other so fiercely on their chariots that they ended up with several broken bones, almost leaving their father without a successor. Caracalla seems to have been the favourite of the Empress, though in later years Julia Domna does come to Geta’s defence, however much in vain.

The Syrian women continued to hold power under the daughters of Julia Domna’s older sister, Julia Maesa who, herself, managed to save the dynasty for a time after the death of Caracalla. Julia Maesa was the mother of Julia Soaemias and Julia Mamaea, both mothers in their turn, of the last Severan emperors, Elagabalus and Alexander Severus. These powerful women held the family together. However, in the end, under Alexander Severus, the loyalty of the army was lost, and what once gave the Severans their ultimate power became their downfall.

There is a lot more to each of the people I have mentioned so briefly here and it is a part of Roman history that is not often explored. However, the Severans made their mark on the Empire and brought about massive changes, from artwork, to marriage for legionaries, to a crippling of the Senate and the extension of Roman citizenship to people all over the Roman Empire. They were strong, religious, varied and flawed, and all make for fantastic fiction!

In the next instalment of The World of Children of Apollo, we’ll be following Lucius Metellus Anguis to Ostia and Rome itself as he leaves North Africa to return home after many years. If you are up for a Roman holiday, be sure to check it out!

What is your favourite imperial Roman family? I’d love to hear from you in the comments below.

Thank you for reading!

Remembrance Day: Healing Wounds with Ancient Greek Tragedy

Remembrance Day is here, in Britain, Canada, and other Commonwealth nations. This is the time of year when we pin poppies on our jackets and hats to show that we remember the sacrifices of the men and women who have served their countries in war.

This is a solemn time of year; many people have known folks who have served in one conflict or another. For myself, my grandfather served in WWI as a young man, my other grandfather in the merchant navy in WWII. I have friends and relatives who have served in the more recent conflicts in Afghanistan and Iraq.

Every year, I try to write a special post around Remembrance Day because I feel it is utterly important not to forget. I often write about war and warriors. It’s something that is always at the front of my mind. I haven’t served in the military myself, but I have the utmost respect for those that have and do.

This year is the 100th anniversary of World War I, the conflict that began the wearing of poppies. Hard to believe it‘s been that long since the Battle of Liège, or since the earth shook with shelling and gunfire at Verdun and the Somme.

We remember the dead, and the ultimate sacrifices they have made, we bow our heads to them as the guns salute on November 11th.

But what about the living?

In war, the casualties are monstrous, but there are those who do manage to come home. What about them?

Those are the troops I want us to think about today.

What prompted this was an article that a colleague of mine gave to me to read, an article that has indeed struck a chord.

This article by Wyatt Mason, in Harper’s magazine, is entitled You are not alone across time – Using Sophocles to treat PTSD.

PTSD stands for Post-traumatic Stress Disorder, and it is, perhaps always has been, a bane on the lives of warriors for ages. It was not always acknowledged as many former troops were simply told to ‘suck-it-up’. But there is a higher level of awareness now, with a variety of treatments being sought by, or offered to, veterans.

In his article mentioned above, Wyatt Mason writes about a unique theatre group called Outside the Wire, and their program ‘Theatre of War’.

The man behind Theatre of War is Bryan Doerries. He has been studying and translating ancient Greek dramas for years.

What is Theatre of War? Using ancient Greek tragedies, particularly Ajax and Philoctetes by Sophocles, Doerries and a small group of rotating actors travel to military bases and hospitals around the world to perform readings of these plays.

There are no stages, props, or pageantry, just Doerries and about three actors sitting at a table. You might think this would be boring, and so might the troops who were ‘voluntold’ to go. But one cannot underestimate the language of Sophocles, the message, and the powerful delivery of the actors.

After attending these ‘performances’, veteran troops come forward to say that they completely relate to the pain of the warrior-characters in these plays, that they do not feel alone. These performances have been helping troops with PTSD with their healing.

Before we go further, here are a few statistics from the article to put things in perspective.

The number of U.S. soldiers who are committing suicide is at an unprecedented level with nearly one per day among those on active duty, and one per hour among veterans. The number is something like 8,000 a year at the moment.

When I read those numbers, my jaw dropped. It seems like there is no heroic return for many of our troops, no ticker-tape parade. It seems more likely that reintegration with civilian society may be more difficult and lonely than war itself.

In 2008, Doerries’ group received $3.7 million from the Pentagon to tour military installations around the world and they have staged more than 250 shows for 50,000 military personnel.

But what is it about Sophocles’ plays that modern troops relate to so much? What leaves these men and women in tears at the end of each performance?

One thing that the article highlighted for me, and of which I was not aware before, is that Sophocles himself was a warrior and commander, his father an Attic amour-maker. Sophocles had lived through the Greek victories over the Persians at Marathon and Salamis, and then served in the bloody years of the Peloponnesian War when the Greeks tore each other apart.

These were deeply traumatic times.

What hadn’t really clicked for me before reading this article was that with military service in Athens being compulsory among men, most of Sophocles’ audience would have been soldiers and veterans of bloody conflicts.

Sophocles spoke to his audience, he addressed the costs of war, the trauma of battle, the grief and rage that lingered long after the laurel wreaths had been handed-out, and the praise of one’s comrades had ceased.

Theatre of War mostly performs two plays for military audiences – Ajax and Philoctetes.

In Greek history/legend, Ajax was one of the greatest of the Greek warriors during the Trojan War. He was a good friend of Achilles, had won numerous battles for the Greeks, and survived one-on-one combat with the greatest of Troy’s heroes, Hector. Ajax inspired his brothers-in-arms.

But even the mighty fall, it seems. In Sophocles’ play, after nine years of fighting on foreign shores, Ajax, who carried Achilles’ body from the battlefield, has a disagreement with Odysseus about who should get Achilles’ god-made armour. Agamemnon and Menelaus decide to award the honour to Odysseus and this insult sends Ajax into a rage. He swears he will kill the sons of Atreus and Odysseus and any others who have insulted him.

However, the gods are not on Ajax’s side. Athena drives him mad and he ends up slaughtering a host of animals in his tent, thinking they are his perceived enemies. Tecmessa, Ajax’s slave woman and consort, relays what happened:

As captives bulls and herdsmen’s dogs and sheep,

Of which a part he strangled, others felled

And cleft in twain; others again he lashed,

Treating those beasts like human prisoners.

Then rushing out, he with some phantom talked,

Launching against the sons of Atreus now,

Now ‘gainst Ulysses, ravings void of sense,

Boasting how he had paid their insults home.

Then once more rushing back into the tent,

By slow degrees to his right mind he came.

But when he saw the tent with carnage heaped,

Crying aloud, he smote his head, and then

Flung himself down amid the gory wreck,

And with clenched fingers grasped and tore his hair.

So a long time he sat and spoke no word.

At last, with imprecations terrible

If I refused, he bade me tell him all,

What had befallen and how it came about.

And I, my friends, o’erwhelmed with terror, told

All that I knew of that which he had done.

Thereat he uttered piercing cries of grief,

Such as had never come from him before,

For in loud lamentations to indulge

He ever held a craven weakling’s part,

And, stifling outcries, moaned not loud but deep,

Like the deep roaring of a wounded bull.

But in this plight, prostrate and desperate,

Refusing food and drink, my hero lies

Amidst the mangled bodies, motionless.

That he is brooding on some fell design,

His wails and exclamations plainly show.

But, O kind friends, ’twas to this end I came,

Enter the tent and aid me if ye can;

The words of friends are desperate sorrow’s cure.

(Sophocles, Ajax)

When the clouds of madness are swept from Ajax’s eyes, he is shamed by what he has done and goes into deep depression. I’m guessing that it must be the same for modern troops who come home and are haunted by the things that they have experienced, seen and done.

We must remember that this is one of the greatest warriors in the army, second only to Achilles. He has Tecmessa, and he has a son, he has had honours heaped upon him, and yet he cannot deal with what he has done. The strain of 9 years of war have had their toll.

What now am I to do, since of the gods

I am abhorred, of the Hellenic host

Hated, to Troy and all this land a foe?

Shall I to their own quarrel leave the Kings,

Unmoor, and homeward cross the Aegean wave?

How can I face my father Telamon?

How can he bear to look upon the son

Who comes to him disgraced, without the prize,

When glory’s wreath has circled his own brow?

(Sophocles, Ajax)

Ajax decides he can no longer be among the living, such is his disgrace. He decides to leave his tent, despite Tecmessa’s protestations. Alone outside, on the earth surrounding Troy, he plants his sword in the ground, point upward, and kills himself…

O death, O death, come and thy office do;

Long, where I go, our fellowship will be.

O thou glad daylight, which I now behold,

O sun, that ridest in the firmament,

I greet you, and shall greet you never more.

O light, O sacred soil of my own land,

O my ancestral home, my Salamis,

Famed Athens and my old Athenian mates,

Rivers and springs and plains of Troy, farewell;

Farewell all things in which I lived my life;

‘Tis the last word of Ajax to you all,

When next I speak ’twill be to those below.

(Sophocles, Ajax)

In the video trailer for Theatre of War, which I link to below, you will see various troops coming forward at the end of a performance to talk about their own demons, and how they very much identified with Ajax and the torment he was feeling.

The suicide statistics I mentioned earlier are telling and terrifying, and they align with these emotions which Sophocles expressed through the hero Ajax over 2000 years ago.

It is wondrous, the therapeutic role that culture and the arts have to play. Doerries and the Theatre of War seem to have tapped into this on a visceral level to engage an audience that has been neglected in decades past. According to the article, the purpose is to “reach communities where intense feelings have been suppressed, in hopes of bringing people closer to articulating their suffering.”

From the numbers of troops, from all ranks, who come forward after the performances, Doerries and the Theatre of War are helping.

One has to wonder what else Sophocles might have produced, and to what effect? Only seven of Sophocles’ plays have come down to us. It is reckoned that he actually produced over 100. There’s a thought! What other issues might he have tackled which involved the ancient warrior and those around him?

One of the other plays that has survived is Philoctetes.

Philoctetes, in history/legend was one of the greatest archers in the ancient world. He was also the inheritor of the bow of Herakles, which that tragic hero bequeathed to Philoctetes when he was the only one who would help Herakles to light his funeral pyre. Another great hero who committed suicide.

Philoctetes had joined the expedition to Troy, but when they first arrived on the other side of the Aegean he was bitten by a snake on his foot. The wound festered and stank and Philoctetes was always in unimaginable pain.

But his comrades did not help him. Instead, because he was so loud and disruptive to the sacrifices and morale, they abandoned him on a desolate island to be alone with his pain and torment.

Sophocles’ play is not about a soldier who is driven to suicide, but rather a soldier who is abandoned, whose friends are not there for him when he needs them most.

His former friends do return, however, after 10 years of war. But it is not for him that they return, but for the bow of Herakles, without which it is said the Greeks cannot win against the Trojans. Odysseus comes to Philoctetes with Neoptolemus, the son of Achilles, to get the bow.

Naturally, Philoctetes is bitter and might have killed his comrades had not Neoptolemus stolen the bow at Odysseus’ insistence. Philoctetes is distraught at losing his one great possession, the thing which has kept him alive.

O pest, O bane, O of all villainy

Vile masterpiece, what hast thou done to me?

How am I duped? Wretch, hast thou no regard

For the unfortunate, the suppliant?

Thou tak’st my life when thou dost take my bow.

Give it me back, good youth, I do entreat.

O by thy gods, rob me not of my life.

Alas! he answers not, but as resolved

Upon denial, turns away his face.

O havens, headlands, lairs of mountain beasts,

That my companions here have been, O cliffs

Steep-faced, since other audience have I none,

In your familiar presence I complain

Of the wrong done me by Achilles’ son.

Home he did swear to take me, not to Troy.

Against his plighted faith the sacred bow

Of Heracles, the son of Zeus, he steals,

And means to show it to the Argive host.

He fancies that he over strength prevails,

Not seeing that I am a corpse, a shade,

A ghost. Were I myself, he had not gained

The day, nor would now save by treachery…

… I return

To thee disarmed, bereft of sustenance.

Deserted, I shall wither in that cell,

No longer slaying bird or sylvan beast

With yonder bow. Myself shall with my flesh

Now feed the creatures upon which I fed,

And be by my own quarry hunted down.

Thus shall I sadly render blood for blood,

And all through one that seemed to know no wrong.

Curse thee I will not till all hope is fled

Of thy repentance; then accursed die.

(Sophocles, Philoctetes)

Philoctetes has experienced not only pain and torment, but extreme isolation for an extended period of time. If he had been able, he likely would have taken out his anger and rage on his former comrades who had come to get him, those who had abandoned him, mainly Odysseus.

But the Gods decide to favour Philoctetes, and in the legend Herakles himself appears and urges his old friend to return to the war with his bow. This Philoctetes does, and he is one of the men who hides in the Trojan Horse. Sophocles’ play does not go into this, but focusses more on the pain of abandonment and isolation.

How many modern troops, or troops through the ages for that matter, would also have experienced such deep pain in isolation, real and figurative?

How many troops come home to family and friends who, despite the very best of intentions, just don’t understand what they have been through? They can’t understand unless they have been there themselves.

The Theatre of War and its performances of Ajax and Philoctetes seems to provide just what is needed for troops who are alone, and depressed, and dealing with PTSD and all the horrors that that entails – a forum of common understanding.

As I said before, I have not served in the military, so I can only imagine what our troops must be going through. However, there is a level on which I can understand some of this that is perhaps related.

It has to do with the study of history in general. Over the years, when I have felt isolated, out-of-place, depressed, or felt difficult emotion to some extreme, I’ve always found comfort in history, the people, the events.

Somehow, studying and trying to understand history, whatever the period, has always helped me to feel more attuned to the world about me, less lonely. No matter how bad I might have thought things were, how little I might have been understood, history, the past, has always shown me that similar things, more difficult things, have happened to others. I think the knowledge of the challenges people in the past have overcome has always given me strength.

I can’t imagine my life without having studied the past. From those difficult teenage years to the present day, the past has always been my comfort and compass, and helped me to move forward however small my steps.

Perhaps that is what our troops, those veterans of extreme emotion, get from listening to their fellow warriors’ voices out of the past?

Bryan Doerries says it at the end of each of his group’s performances:

“Most importantly, if we had one message to deliver to you, two thousand four hundred years later, it’s simply this: You are not alone across time.”

So, this November 11th, and all through the year, I will ever spare a thought or prayer for warriors past and present. It shouldn’t matter what you think of the kings or politicians who sent them to battle for whatever ends.

If history has taught me anything, it is that warriors through the ages have faced incredible challenges and horrors, and for that they deserve our compassion.

Lest we forget…

Thank you for reading.

If you would like to learn a bit more about the Theatre of War, be sure to visit the website and spread the word. You can also watch the video trailer which shows some of the work they do and includes troops expressing their feelings post-performance. Powerful stuff!

http://youtu.be/RHTVBq5nkj8?list=PLaGnq8H7GaVKuX3GVeir9DZ8W8fDvkUbc

I would also recommend watching some of their performances. Below are clips of both Ajax and Philoctetes being performed by Theatre of War.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Fus0JYIxFtk&index=1&list=PLaGnq8H7GaVKuX3GVeir9DZ8W8fDvkUbc

Click HERE to watch a performance of Ajax by Theatre of War.

Click HERE to watch a performance of Philoctetes by Theatre of War.

A Short History of Halloween

This Friday night is the night that many children, and adults, have been looking forward to. It’s a time to get dressed up, carve a pumpkin, eat lots of candy and party it up incognito.

Halloween, as we know it, has evolved over time and like many of our current traditions, it has its roots in the distant past. There are many theories about which traditions or ancient festivals are at the heart of our modern Halloween or, All Hallow’s Eve.

Some maintain that it’s a Christian festival linked to All Saints’ Day on November first, and All Souls’ Day on November second. Historically, during these two Christian festivals, ‘soul-cakes’ would be made and handed out to the poor who would go door-to-door. This was seen as a way of praying for the souls that were then in Purgatory. Halloween is indeed a good time to pull out your copy of Dante’s Inferno.

Another candidate thought to contribute to the origins of Halloween is the ancient Roman festival of Pomona. Unlike many Roman divinities who had their original Greek counterpart, Pomona was a uniquely Roman goddess or wood nymph who watched over and protected the fruit trees at this harvest time of year. The connection to Halloween seems a little less likely to me, but it’s still an interesting festival, and apples do figure largely in some Halloween activities. Who hasn’t bobbed for apples?

However, when it comes to Halloween the most likely candidate for its origins still seems to be the ancient Celtic festival of Samhain (pronounced ‘saw-wen’). This was a sacred time of year for the ancient Celts of Gaul, Britain, Scotland and Ireland – the time of the death of summer. In Ireland, Scotland and the Isle of Man it was known as Samhain, in Wales and Cornwall it was known as Calan Gaeaf and Kalan Gwav respectively.

This was the time of the harvest, of bounty, but also of death, which was a part of the cycle of life. It was also a time of year when the door to the Otherworld was opened, the veil at its thinnest. The souls of the dead were said to revisit their former homes where people would set places for them at table. Other beings, such as fairies, roamed the land as well, some good, some mischievous, and others harmful.

One way in which people, young and old, would avoid being noticed by spirits of the departed was by wearing a costume or ‘guising’ as it was called. If you had wronged a family member in the past, or even trampled a fairy ring, you were better off having a good costume!

The idea of trick-or-treating in 19th century Ireland was a way that folks went door-to-door gathering food as offerings for the fairies or fuel for the purifying bonfires of Samhain. Fire and its light served as protection during the thinning of the veil and the carving of pumpkins into Jack-O-lanterns served to scare spirits and fairies away.

Even if you don’t celebrate Samhain or Halloween in some way, shape or form, it is nonetheless interesting how ancient traditions survive thousands of years, from the feeding of the dead in ancient Egypt and Greece, to the Roman and Celtic festivals of the harvest. Halloween seems to be a melding of many different aspects of various cultural traditions.

So, Friday night, whether you are lighting a candle, carving a pumpkin, handing out candy or going all out with your ‘guising’, take a moment to remember that it’s not just some modern-day, consumer-driven tradition that you’re taking part in.

Remember that you’re taking part in an ancient rite at a sacred time of year for many cultures, and that maybe, just maybe, you are being watched from the other side of the veil between this world and the next…

Stay safe and Happy Halloween!

Thank you for reading.

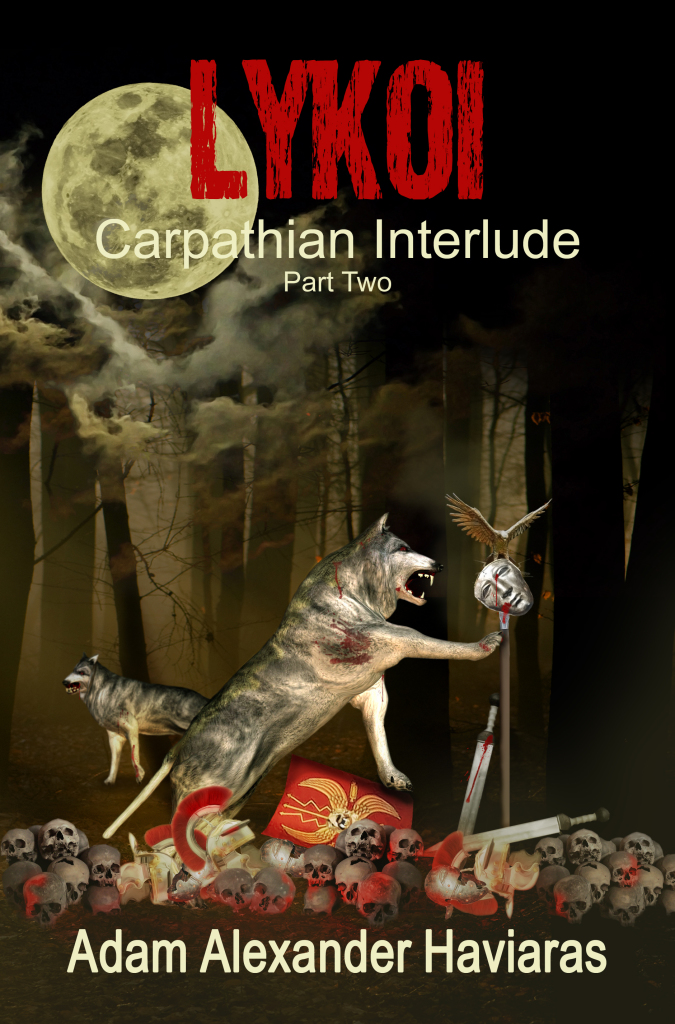

LYKOI Unleashed!

Today is Launch Day!

That’s right, LYKOI – Carpathian Interlude Part II is now available from Amazon, Kobo, and iTunes.

For just a few days, Eagles and Dragons Publishing is offering LYKOI for a special launch price of $.99 cents before it goes up.

So, if any of you have friends and family who like ancient history and historical fantasy/horror, please do spread the word!

I’ve really enjoyed writing this book and interlacing the supernatural themes and beliefs of LYKOI with the historical events of the Varus disaster. Also, getting deeper into the minds of the scarred characters has truly been a fascinating and melancholy experience.

I’m currently writing Carpathian Interlude Part III, the working title of which is ‘THANATOS’.

This story is going to get even darker and delve into some very ancient myths around Zoroastrianism and the origins of Mithras. We will also find out who this Carpathian Lord actually is – and you won’t expect it!

Most importantly, I’d like to thank many of you for your support, encouragement and comments, the many personal e-mails, and your help in spreading the word about the series across social media. It all means a great deal, and the series’ success would not be possible without you.

So, thank you once more, and Happy Reading!

The World of LYKOI – Monsters in the Dark – Werewolves in the Ancient World

This post of The World of LYKOI is when history and fantasy morph into the historical horror of the Carpathian Interlude series.

As we know, Emperor Augustus’ three legions, under the command of Publius Quinctilius Varus, were slaughtered in the forests of Germania in an unprecedented defeat for Rome. Fear has a stranglehold on the Roman world, including the emperor, and everyone looks to place blame, to find an explanation.

As Cassius Dio said, it “could have been due to nothing else than the wrath of some divinity.” What else could it have been? The omens were terrible. According to ancient sources, the temple on the Field of Mars in Rome was struck by lightning, locusts invaded the city, and a statue of Victory in the north turned its back on Germania. Surely a bunch of German barbarians under the command of a traitor could not have done this alone? A god must have been involved!

Or something else…

This question is something that the historical fantasy novelist truly relishes. The opportunity to put hindsight and modern doubt aside, and step into the mindset of the ancient world, replete with all of its folk and religious beliefs, its strong superstitions and maybe, just maybe, some ancient knowledge of which we are completely ignorant.

What if Arminius and the Germanic tribesmen received help from someone… something… who also had an interest in halting Rome’s northern advance?

Lykoi is the Greek word for ‘wolves’, and in this story they are not the shy, intelligent, loyal, and enigmatic animals we know them to be today.

Throughout history, the wolf has been demonized and hunted to the point of extinction in most of Europe. Every child in the west has grown up with stories of evil wolves haunting the forests surrounding settlements, slavering beasts who slaughter livestock and people alike and who revel in the blood of their kills.

And what takes the horror of the wolf one step further? – A man who turns into a wolf – a Werewolf.

In doing the research for LYKOI, I discovered that the legend of the Werewolf was not a medieval fabrication as I had previously thought. In the ancient world, there are also references to Lycanthropes, or Werewolves.

In the 5th century B.C. the historian Herodotus wrote about a people known as the Neuri who lived in the Scythian lands:

The Neuri follow Scythian customs; but one generation before the advent of Darius’ army, they happened to be driven from their country by snakes; for their land produced great numbers of these, and still more came down on them out of the desolation on the north, until at last the Neuri were so afflicted that they left their own country… It may be that these people are wizards; for the Scythians, and the Greeks settled in Scythia, say that once a year every one of the Neuri becomes a wolf for a few days and changes back again to his former shape. Those who tell this tale do not convince me; but they tell it nonetheless, and swear to its truth. (Herodotus; Histories Book IV 105)

Herodotus could be a picky historian, so for him to include this reference in his work, while expressing his own doubt at the same time, speaks to the possibility that the belief of the locals where he obtained this story was strong indeed.

But there are stories of wolf men going even farther back. The Roman poet, Ovid, writing during the reign of Emperor Augustus, recounts the tale of the Arkadian King, Lycaon, in his famous work Metamorphoses.

King Lycaon was a Peloponnesian king from c. 1550 B.C. He was an arrogant tyrant who tried to pull a fast-one on Zeus [Jupiter], the king of the gods, by feeding the immortal human flesh. Here is Ovid’s account in the god’s own words:

I traversed Maenalus where fearful dens abound, over Lycaeus, wintry slopes of pine tree groves, across Cyllene steep; and as the twilight warned of night’s approach, I stopped in that Arcadian tyrant’s realms and entered his inhospitable home:—and when I showed his people that a God had come, the lowly prayed and worshiped me, but this Lycaon mocked their pious vows and scoffing said; ‘A fair experiment will prove the truth if this be god or man.’ and he prepared to slay me in the night,—to end my slumbers in the sleep of death. So made he merry with his impious proof; but not content with this he cut the throat of a Molossian hostage sent to him, and partly softened his still quivering limbs in boiling water, partly roasted them on fires that burned beneath. And when this flesh was served to me on tables, I destroyed his dwelling and his worthless Household Gods, with thunder bolts avenging. Terror-struck he took to flight, and on the silent plains is howling in his vain attempts to speak; he raves and rages and his greedy jaws, desiring their accustomed slaughter, turn against the sheep – still eager for their blood. His vesture separates in shaggy hair, his arms are changed to legs; and as a wolf he has the same grey locks, the same hard face, the same bright eyes, the same ferocious look. (Ovid; Metamorphoses, Book I, 216)

In mythology it was not unusual to find the gods punishing humans by turning them into animals, but the example of Lycaon is noteworthy. His sacrilege to Zeus, his hubris, is unforgiveable. The king of the gods could have turned the wicked mortal into anything, any animal or insect, but Zeus chose to turn Lycaon into a wolf man, a being in pain who could not be satiated, who kept his awareness despite not being able to speak. Lycaon is turned into a beast who preys upon beasts, ‘terror-struck’ and yet also terrifying.

There was, it seemed, always a price to pay for being turned into a Werewolf, or ‘Lykos’. It was a painful, horrifying existence.

Another example from ancient literature that stands out is Gaius Petronius’ Satyricon, believed to originate from sometime during the reign of Nero in the 1st century A.D. Petronius’ work is one of the few surviving Roman novels, and it is mostly a satire of life in ancient Rome.

However, one of the episodes involves a character who heads-out one night to his woman’s home with a soldier friend who, as they walk along the road, turns into a Werewolf. Far from being a humorous episode, Petronius writes in detail about what happens:

I seized my opportunity, and persuaded a guest in our house to come with me as far as the fifth milestone. He was a soldier, and as brave as Hell. So we trotted off about cockcrow; the moon shone like high noon. We got among the tombstones: my man went aside to look at the epitaphs, I sat down with my heart full of song and began to count the graves. Then when I looked round at my friend, he stripped himself and put all his clothes by the roadside. My heart was in my mouth, but I stood like a dead man. He made a ring of water round his clothes and suddenly turned into a wolf. Please do not think I am joking; I would not lie about this for any fortune in the world. But as I was saying, after he had turned into a wolf, he began to howl, and ran off into the woods. At first I hardly knew where I was, then I went up to take his clothes; but they had all turned into stone. No one could be nearer dead with terror than I was. But I drew my sword and went slaying shadows all the way till I came to my love’s house. I went in like a corpse, and nearly gave up the ghost, the sweat ran down my legs, my eyes were dull, I could hardly be revived. My dear Melissa was surprised at my being out so late, and said, ‘If you had come earlier you might at least have helped us; a wolf got into the house and worried all our sheep, and let their blood like a butcher. But he did not make fools of us, even though he got off; for our slave made a hole in his neck with a spear.’ When I heard this, I could not keep my eyes shut any longer, but at break of day I rushed back to my master Gaius’s house like a defrauded publican, and when I came to the place where the clothes were turned into stone, I found nothing but a pool of blood. But when I reached home, my soldier was lying in bed like an ox, with a doctor looking after his neck. I realized that he was a werewolf, and I never could sit down to a meal with him afterwards, not if you had killed me first. Other people may think what they like about this; but may all your guardian angels punish me if I am lying. (Petronius; Satyricon 62)

Petronius’ character was either drinking some heady wine that night, or else his soldier friend had other major issues.

The point of these texts is that there was an awareness of Werewolves in the ancient world, or of Lycanthropy, a psychological disease that the famous physician Galen apparently wrote about, in which a person believed they were part wolf and had the ravenous appetite to match that belief.

Now back to the LYKOI and the Carpathian Interlude.

The Varus disaster was an unbelievable event, behind which much darker powers are at play. Throughout this series, the powers of Light (Mithras and Rome) and Dark (The Carpathian Lord and the ‘Barbarians’) are locked a battle that has been raging for ages.

And Gaius Justus Vitalis, his men, and the boy, Daxos, are caught up in the middle of it. The war rages on many fronts – in the dark of the forests of Germania and Carpathia, on the battlefields of the frontier, and mostly in the hearts and minds of Mithras’ own soldiers, his Heliodromus and his Miles, Gaius and his men.

This is a story that will haunt you and leave the screams of Rome’s dead and dying men ringing in your ears for a long time to come, just as it did for the people of Rome over two thousand years ago.

Thank you for reading!

LYKOI – Carpatian Interlude Part II is now available for pre-order, so be sure to grab your copy today!

It is available from Amazon, Kobo, and iTunes/iBooks.

If you are looking for a haunting Halloween read that takes place in the ancient world, this is the book for you!

Also, if you have not read IMMORTUI – Carpathian Interlude Part I, it is available for Free from Kobo and iTunes/iBooks for the next couple days, and for $.88 cents from Amazon. Don’t miss out, and do please spread the word!

If you are curious about IMMORTUI or LYKOI, you can read some lengthy excerpts HERE.

The World of LYKOI – The Varus Disaster

Have you ever wondered why forests are so often the setting for nightmares?

Think about it. It’s true.

I remember a recurring nightmare that I had when I was a child: I’m in a dark forest, walking by myself. My feet crunch on a carpet of dead leaves in a slow, steady rhythm. Then a second set of footsteps, comes into my hearing, only they’re faster. They’re pursuing me. I begin to panic, and run. I yell but the woods devour my cries. I believe someone is chasing me, and my heart is close to bursting… And then I wake up.

That might not seem scary now, but when you are 6 it’s another story.

Nightmares are fascinating and curious. As a child I didn’t know that the quickening steps of my forest pursuer were really the sound of the blood pulsing in my ear as it pressed into my pillow. Those woods were terrifying to me.

Think about the woods again. How many of you have read or heard scary stories that take place in a forest? For ages, the woods or any kind of forest, have been shadow realms of the unknown, places of magic and nightmare, of beasts and death.

But there is a reason why forests have become such monsters in and of themselves. Not all tales of horror in the woods are fabricated by active, childish minds.

As I mentioned last week, the Carpathian Interlude series revolves around a particular event in Roman history known as the Varus Disaster. It took place in A.D. 9, during the reign of Emperor Augustus, and it was truly the stuff of nightmares.

Public Quinctilius Varus was a patrician Roman general and member of the imperial circle who had been put in charge of the administration of Germania, which had only recently been tentatively subdued by Rome. Varus had previously had success governing provinces in Africa, Syria, and Judea, so it was believed he would be more than capable of handling Germania.

Varus is said to have also had a reputation for being a tyrant who inflicted brutal punishment on the people he was governing and squeezing taxes out of.

It’s safe to say that Varus thought he was quite secure in his position. He was a skilled administrator by Roman standards, had a proven track record, the bloodline to back it up, and a staff of trusted advisors.

Among the people on Varus’ staff was a man named Arminius. Does that name ring a bell?

Arminius was the son of Segimerus, the chieftain of the Cherusci, a Germanic tribe that had bent the knee to Rome. As surety for their father’s good behaviour, Arminius and his younger brother Flavus were sent to Rome when they were just boys. We’ll focus on Arminius.

Arminius grew up in Rome, learned the ways of Roman life, and politics, and martial prowess. He began to make a name for himself and was admitted to the Equestrian order to become a cavalry officer.

When Varus was assigned to Germania, Arminius went with him as one of his most trusted advisors and skilled officers. In fact, it’s said that Varus and Arminius regularly dined together; no doubt Varus valued Arminius’ advice in governing the lands of his former people.

This is the seed of the nightmare of which I spoke earlier.

In the late summer of A.D. 9, Publius Quinctilius Varus led three legions (the XVII, XVIII, and XIX Legions) deep into Germania to collect taxes and tribute. Varus also had with him six auxiliary cohorts, three cavalry alae, slaves, and camp followers consisting of women, children, merchants and tradesmen. This was a large, slow-moving army. Because they were in a dense forest, the line of march was thin, and stretched over 15-20 kilometres.

But Varus felt he had little to worry about and was so confident that he didn’t event send scouts ahead.

Then Arminius brought word of an uprising to Varus who sent the former to take care of it. Varus was warned against Arminius by another German advisor, Segestes, who was actually a relative of Arminius. But Varus ignored Segestes’ warnings not to trust Arminius and so the nightmare really began.

Rather than supressing the uprising, Arminius instead disappeared into the forest to rally the allied Germanic tribes and attack the Roman forces.

The mountains had an uneven surface broken by ravines, and the trees grew close together and very high. Hence the Romans, even before the enemy assailed them, were having a hard time of it felling trees, building roads, and bridging places that required it. They had with them many wagons and many beasts of burden as in time of peace; moreover, not a few women and children and a large retinue of servants were following them… For the Romans were not proceeding in any regular order, but were mixed-in helter-skelter with the wagons and the unarmed, and so, being unable to form readily anywhere in a body, and being fewer at every point than their assailants, they suffered greatly and could offer no resistance at all. (Cassius Dio, The Roman History 20)

I thought my nightmare in the forest was horrifying.

For three days the Romans were ambushed by the Germanic tribesmen. Three days in the tangle of the Teutoburg Forest, the bogs and brambles, the rivers, and marshes, violent storms and… the dark.

Varus, the legions, and the camp followers had no chance. Arminius had learned how Romans fought, how to weaken them, and how to defeat them. He had laid his plans well, and after three days of desperate fighting, the Romans made their last stand at a place known today as Kalkriese.

In the end, Varus and some of the other officers took their own lives rather than fall into the enemy’s hands. Perhaps, as well as fear, it was Varus’ shame that let him to do such a thing. The total number of Roman dead? – about 20,000.

… three legions were cut to pieces with their general, his lieutenants, and all the auxiliaries… they say that he [Augustus] was so greatly affected that for several months in succession he cut neither his beard nor his hair, and sometimes he would dash his head against a door, crying: “Quinctilius Varus, give me back my legions!” And he observed the day of the disaster each year as one of sorrow and mourning… (Suetonius; Life of Augustus 23)

There is no mistaking that this was indeed a real-life nightmare for Rome, and this crushing defeat struck fear into the hearts of everyone from the lowest Suburan sewer rat right the way up to Augustus himself.

Years later, when Germanicus went into Germania to find the remains of the fallen legions, he came to the site of the struggle.

…they [Germanicus and his men] visited the mournful scenes, with their horrible sights and associations. Varus’s first camp with its wide circumference and the measurements of its central space clearly indicated the handiwork of three legions. Further on, the partially fallen rampart and the shallow fosse suggested the inference that it was a shattered remnant of the army which had there taken up a position. In the centre of the field were the whitening bones of men, as they had fled, or stood their ground, strewn everywhere or piled in heaps. Near, lay fragments of weapons and limbs of horses, and also human heads, prominently nailed to trunks of trees. In the adjacent groves were the barbarous altars, on which they had immolated tribunes and first-rank centurions. Some survivors of the disaster who had escaped from the battle or from captivity, described how this was the spot where the officers fell, how yonder the eagles were captured, where Varus was pierced by his first wound, where too by the stroke of his own ill-starred hand he found for himself death. They pointed out too the raised ground from which Arminius had harangued his army, the number of gibbets for the captives, the pits for the living, and how in his exultation he insulted the standards and eagles. (Tacitus, Annals 1.61)

People must have thought that the gods had turned their backs on Rome.

So how does this fit with the Carpathian Interlude?

When I think of the nightmare of the Varus disaster, what it must have felt like for the troops and camp followers who knew that the barbarians would kill them at any moment, I feel terror for them. The shock, the surprise, the desperation as people were dying all around them in such horrible ways must have been truly overwhelming.

I wanted to take the terror one step further. What if Arminius had more than just the element of surprise on his side? What if he had allied himself with a darker, more powerful enemy in his desperation to crush Rome and assume hegemony over the Germanic tribes?

This is the path I’ve taken in turning this historic event into historical horror.

Cassius Dio describes the omens that Rome witnessed in the aftermath of the disaster, the fearful belief of Augustus and others that the gods were indeed angry:

For a catastrophe so great and sudden as this, it seemed to him [Augustus], could have been due to nothing else than the wrath of some divinity; moreover, by reason of the portents which occurred both before the defeat and afterwards, he was strongly inclined to suspect some superhuman agency. (Cassius Dio, The Roman History 24)

In LYKOI – Carpathian Interlude Part II, it’s not a god that has laid the Romans low in the wooded shadows of Germania. The enemy that has defeated Rome is the one that Gaius has dreaded ever since his battle with the Immortui in Part I.

Here is the description for LYKOI – Carpathian Interlude Part II:

In the year A.D. 9, three legions of the Emperor Augustus are massacred in the forests of Germania. It is a defeat that fills the heart of the Roman Empire with terror.

Meanwhile, in Rome, Gaius Justus Vitalis and his surviving men are struggling with the trauma of their battle with the Immortui in the Carpathian Mountains, an experience that has changed them forever.

When shades of the dead whisper to Gaius that something more sinister and terrible is responsible for Rome’s recent defeat in Germania, he knows that his days of peace are numbered.

Aware of Gaius and his men’s unique experiences, the Emperor orders them across the Danube frontier to discover what has happened to the lost legions, and to bring the perpetrators to justice. The stakes are high, and Gaius knows that if he does not succeed, he and his family are doomed.

With a handful of warriors, and a boy who may hold the key to his enemy’s defeat, Gaius crosses the frontier to hunt down the truth behind the horrors he suspects.

Only when fear is at its most intense, can true heroism come to the light.

LYKOI’s release date is October 25th, 2014, but it is available for pre-order from Amazon, Kobo, and iTunes/iBooks if your interest is piqued. It will be released at a special launch price for a short period time.

Also, beginning on October 12th, IMMORTUI (Carpathian Interlude Part I) will be available for $.99 cents on Amazon and for Free on Kobo and iTunes for a short time. If you haven’t read it, you’ll want to take advantage of this special offer.

I hope you’ve enjoyed this sneak peek at the world of LYKOI. I’ll be back next week with a look at what Gaius and his men will face in the dark forests of Germania.

Thank you for reading!

If you are interested in more of the history of the Varus disaster, as well as the finds from Kalkriese, the video below is an excellent documentary for getting stuck into the nightmare:

http://youtu.be/jDKLQAraxe8?list=PLaGnq8H7GaVLH-dDaUlKHpy-JcMqwmI5F